The concept of “Christian nationalism” was developed in the US to explain the link between radicalised religious attitudes and incautious behavior during the pandemic. Researchers Tymofii Brik, Maria Chayinska, and Tornike Metreveli show that this concept could be applied to Ukraine as well. New polling data collected on the eve of Easter 2021 confirm that there is a strong positive correlation between “Christian nationalism” of Ukrainians and their anti-vaccination attitudes.

God-chosen nation

Why do some people not wear masks and ignore other health protocols during the pandemic? Usually, researchers explain it with low trust in governments, polarization of media, and radicalization of politics. Yet, most recent studies conducted in the US also showed the importance of the so-called “Christian nationalism”. The term Christian nationalism was coined in the US to explain a fusion of American civic life with Christian identity and culture. As the argument goes, this ideology paints Americans as God’s chosen–and possibly protected–people. The adherents of this ideology support the notion that “The United States were founded as a Christian nation” or that “America holds a special place in God’s plan”. Americans who adhered to this ideology were less likely to wear a mask, sanitize their hands, and even approve vaccines . Interestingly, religious commitment (religious service attendance, prayer frequency, and religious importance), contrary to Christian nationalism, was positively associated with precautionary behaviors. In simple words, religious commitment was found to promote more prosocial values and behaviors unless it is blended with the specific worldview of Christian nationalism.

Although the concept of Christian nationalism has been quite popular in the US, it has been rarely explored elsewhere due to the specific context of US politics and history. Nevertheless, we suggest this concept could be used to study preventive public health behavior in the context of Ukraine. Over decades, a vast amount of research piled showing that the realms of Ukrainian religion and politics have been entangled [1]. Surveys showed that electoral behavior correlates with national sentiments of respondents [2], media studies showed that Ukrainian politicians have increasingly appealed to religious symbols and narratives [3], and statistical models showed that religious behavior of Ukrainians was mediated by national preferences [4]. All in all, these studies point out to a strong link between national and religious identities which interplay to predict a wide array of group practices and behaviours. Therefore, the idea that Christian nationalism can explain incautious behavior and anti-vaccination attitudes in Ukraine is both theoretically grounded and appealing.

How did we measure Christian nationalism?

In order to investigate the role of Christian nationalism in predicting anti-vaccination attitudes in Ukraine, we collected new polling data using the Gradus application. This is the online panel which recruits urban Ukrainians aged 18-60 who live in cities with a population of 50,000 or more. We translated the original six questions from the Baylor Religion Surveys and the Chapman University Survey of American Fears adapting them for the Ukrainian context:

Responses range was from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

- “The government should declare Ukraine a Christian nation” (mean 3.5).

- “The government should advocate Christian values” (mean 3.5).

- “The government should enforce strict separation of church and state (reverse coded)” (mean 1.3).

- “The government should allow prayer in public schools” (mean 2.2).

- “The government should promote religious symbols in public spaces” (mean 2.2).

- “The success of Ukraine is part of God’s plan” (mean 2.5).

We created a final scale averaging the values of these six items (Cronbach’s alpha = .87). As Table 1 suggests, the average value of this scale was quite similar for all regions, both genders, and all age groups (about 2.6). While the average value of this scale for atheists was 1.6, religious respondents ranked higher (e.g., 3.1 for Greek Catholics).

Table 1. Average value of the Christian nationalism index (after applying weighs by gender, religion and region).

| Mean | SE | |

| Regions (no statistical differences between regions) | ||

| East | 2.5 | 0.12 |

| West | 2.7 | 0.21 |

| North | 2.6 | 0.12 |

| Center | 2.7 | 0.12 |

| South | 2.6 | 0.13 |

| The city of Kyiv | 2.4 | 0.13 |

| Soc-dem (no statistical differences between relevant groups) | ||

| Higher education | 2.5 | 0.05 |

| Below higher education | 2.7 | 0.13 |

| Men | 2.6 | 0.08 |

| Women | 2.6 | 0.08 |

| 18-24 years | 2.5 | 0.19 |

| 25-34 years | 2.4 | 0.11 |

| 35-44 years | 2.7 | 0.06 |

| 45-54 years | 2.7 | 0.13 |

| 55-60 years | 2.7 | 0.20 |

| Religious groups (statistical difference between atheists and all other groups)+ | ||

| Greek Catholics | 3.1 | 0.11 |

| Orthodox (Moscow Patriarchate) | 2.9 | 0.13 |

| Orthodox (Kyiv Patriarchate) | 2.9 | 0.17 |

| Orthodox Church of Ukraine | 2.9 | 0.08 |

| Orthodox (no partition) | 2.7 | 0.11 |

| Atheists | 1.6 | 0.12 |

+we checked statistical differences with ANOVA and regression models.

Christian nationalism and anti-vaccination

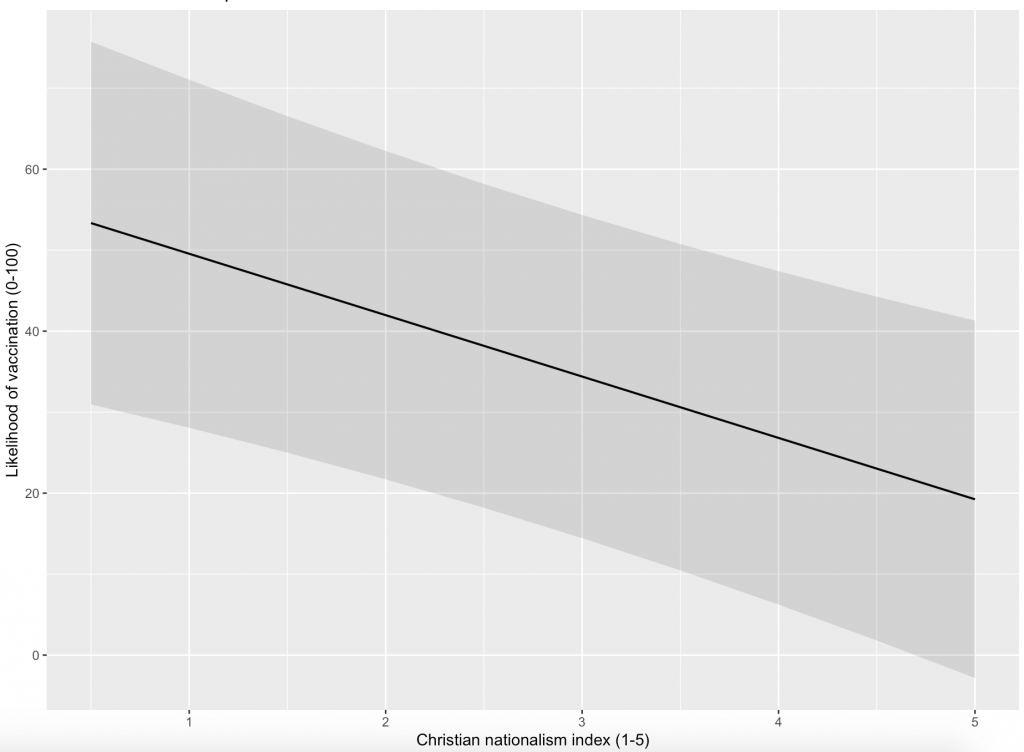

We asked our respondents to give their subjective evaluation of whether they will take a vaccine against the Covid-19, once it is available for them (on a scale from 0 to 100). After controlling for religious affiliation, regions, and socio-demographic profile of respondents, the index of Christian nationalism was significant in predicting anti-vaccination attitudes of Ukrainians. In simple words, the more strongly participants adhered to the ideas of Christian nationalism the less likely they were to get an anti-COVID vaccine.

Figure 2. Linear regression. Likelihood of getting a vaccine (after controlling for religious commitment, religious groups, regions, and socio-demographic profile).

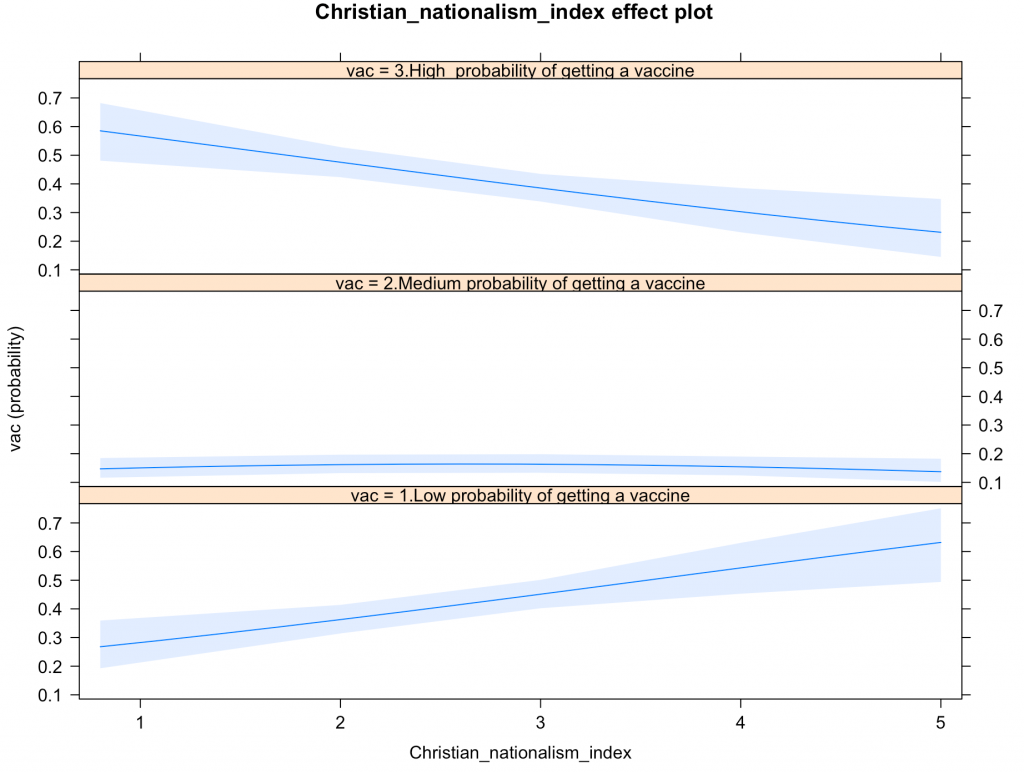

Given that many respondents provided answers which gravitated around extreme values of the scales (very low, precisely at the middle, and very high values), we also recorded the scale of vaccination from 0-100 into a categorical one (“low probability” for values below 49, “medium probability” for 50, and “high probability” for above 51). The results of our analysis were robust to this specification.

Figure 3. Ordered logit regression. Likelihood of getting a vaccine (after controlling for religious commitment, religious groups, regions, and socio-demographic profile).

It is also worth mentioning that, similarly to the previous findings in the US, religious commitment per se did not play a crucial role. The role of the frequency of religious behavior (e.g., praying, attending churches) was found to be not significant. Interestingly, we also found that Greek Catholics were more likely to accept vaccination, while Orthodox believers of the Moscow Patriarchate were less likely to accept it. This is in line with previous findings that religious commitment does not stimulate incautious behavior unless blended with the specific worldview of Christian nationalism.

Summary and conclusion

In Ukraine, similarly to the US, Christian nationalism appears to be a strong predictor of anti-vaccination attitudes. Ukrainian religious groups have been criticized for incautious behavior during the pandemic (especially during the Easter celebrations). Our data suggest that religious commitment per se does not pose a threat to public health. Instead, policy and media debates should focus on specific worldviews and discourses which blend nationalism and Christianity.

[1] Metreveli, T. (2020). Orthodox Christianity and the Politics of Transition: Ukraine, Serbia and Georgia. London: Routledge.

[2] Yelensky, Viktor. 2010. “Religiosity in Ukraine According to Sociological Surveys.” Religion, State & Society 38: 213–27.

[3] Marchenko, Alla. 2017. “Religious Rhetoric, Secular State? The Public References to Religion by Ukraine’s Top Politicians.” Euxeinos: Culture and Governance in the Black Sea Region 24: 39–51.; Denys Shestopalets, “Churches, Politics, and Ideological Struggles in Ukraine: The Case of the Euromaidan Protests (2013–2014)”. Politics, Religion & Ideology, vol. 21, no. 1 (2020), 46-67

[4] Brik, T. (2019). When church competition matters? Intra-doctrinal competition in Ukraine, 1992–2012. Sociology of Religion, 80(1), 45-82.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations