Denial of historical record and incitement to genocide must be clearly labeled by a library; Ukrainian readers should not be made to settle for the books in Russian

On November 8th, many Americans performed the most sacred voting rites of democracy in a local library or a school. It is one of the many special roles of public libraries in the life of the country. Public libraries would be yet another way to welcome Ukrainians who find a temporary sojourn on the shores of the Atlantic and the Pacific from the aggression of the Russian Federation. Are the libraries ready?

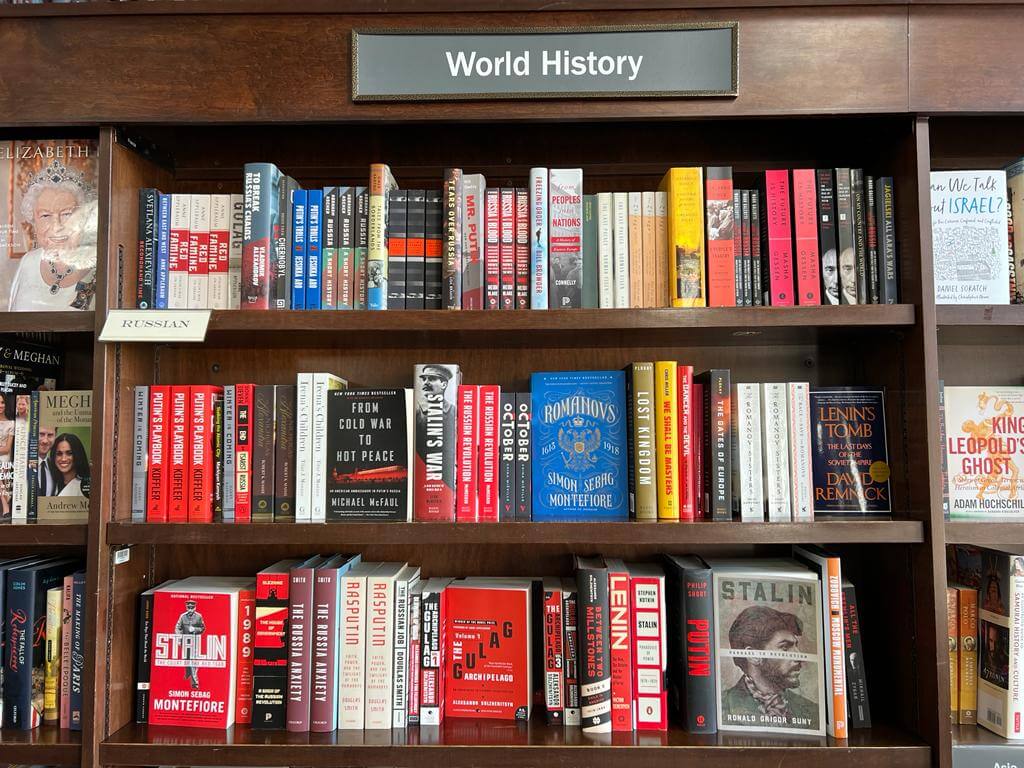

Over the last twenty years, books in Ukrainian language had difficulty maintaining any presence in the library practice. Ukrainian books that ordinary readers could check out and read at home (we will call them a circulating collection) were a museum curiosity relegated to items published fifty years ago and a haphazard selection of a dozen of items. Circulating collections of books in Ukrainian available to the general public have not exceeded three hundred items over considerable time in major metropolitan libraries. This was not happening for every language. Russian language circulating collection has touched a round number of 10,000 in one large public library system, along with a strong system of community outreach.

The conditions of Ukrainian books in major public library systems have neatly recreated, albeit under different circumstances, a Russian imperial system codified in Ems Ukaz (Emsk Decree of 1876) that has effectively banned use of Ukrainian in the public sphere. One stated rationale was the same as one hundred fifty years ago in the Russian Empire. One library has explained a lack of books in Ukrainian, in a meeting after 2014, with a simple fact that the Ukrainian readers, according to the sources that the library trusted, can be expected to read in Russian in any case.

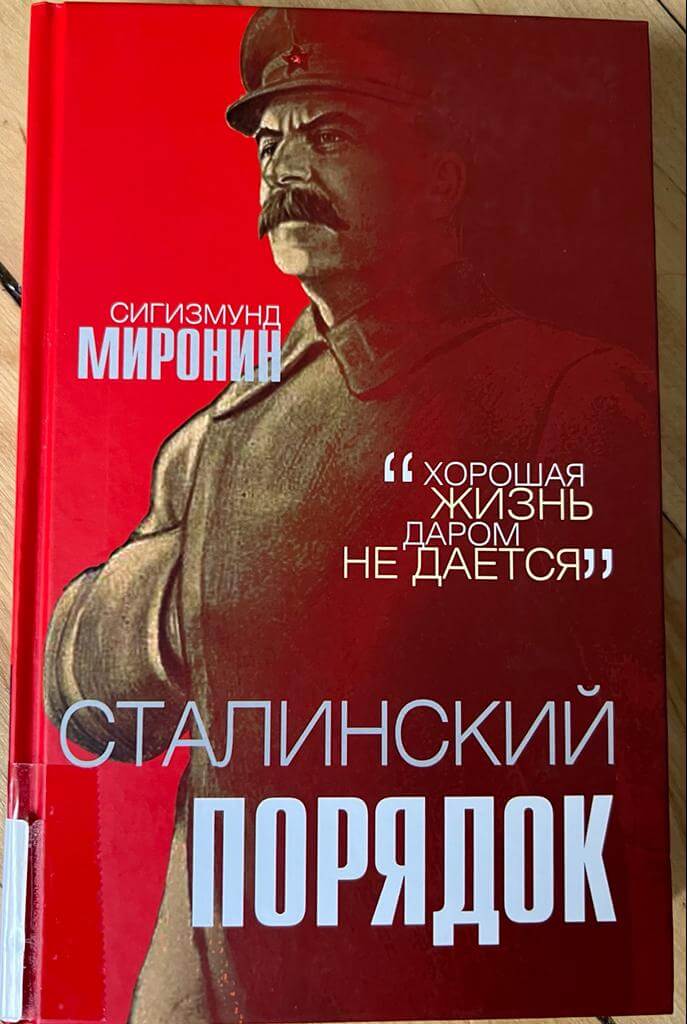

The collection in Russian that was supposed to serve the prospective readers of Ukrainian books was comprehensive in its own way. It was a reflection of the society where the government is “inciting a genocide”, in the meaning of New Lines/Raoul Wallenberg report. Let us examine the most salient examples found in one public library collection, “Stalin’s Order: Good Life Does Not Come for Free”. The abstract reads as follows (page 4): “This book reviews the year 1937, mysterious and much mythologized in our country [Russian Federation], and abroad; based on the broad review of primary, documentary evidence. The author’s view is that the events of this year are directly related with the struggle of J.V.Stalin to strengthen the Soviet state, to keep the government clear of the individuals who either opposed continued state building or were involved in economic or political crimes”. Of course, “keeping clear” means a lengthy prison term with low chance of survival or prompt execution. On page 6th, we learn that Khruschev speech on February 25th, 1956 has started the “time bomb under the foundations of the mighty social organism that J.V.Stalin has created over the years of his rule”. Chapter 1 (page 12) is titled “Myth of “Holodomor” of 1932-33”. Do we need the books that call murder “keeping clear” in a history book for an average reader? Does one need to spell out the correspondence between the pages of the book and the many methods of genocide described in New Lines/Raoul Wallenberg report–“denial of the existence of a Ukrainian Identity”, “accusations in a mirror”, “dehumanization”, “construction of Ukrainians as an existential threat”, and “conditioning the Russian audience to commit or condone atrocities”?

Does the library profession have many choices for its response? As usual there are several choices that the profession has. There are a number of public libraries that have recently strengthened their Ukrainian circulating book collections–Chicago Public Library, Queens Public Library and Seattle Public Libraries. Similarly, the profession does not have to live with the status quo of genocidal literature living normally within its walls.

We advocate an approach that acknowledges gravity of the matter and calls for a systemic solution that has always been at the core of the library profession–naming the books through a classification system based on careful reading.

We do know that the Library of Congress classification system has a category of “spurious research” that has in fact been highlighted by American Library Association (ALA) in cases of denial of historical record. “Holodomor denial” is yet another Library of Congress classification category (Dobczanskyi, Affirmation and Denial…, Holodomor Studies, 1, No.2 (summer-Autumn 2009), 155-164). Books under “Holocaust denial” category are properly labeled and placed in a specially marked location in major metropolitan libraries. Public libraries should examine their collections and name the books that incite genocide.

Public research libraries do have the resources to conduct such a review, along with the staff of circulating collections; academic institutions will be able to contribute their resources. The Library of Congress, along with major research centers in public libraries and private universities, can also take the lead.

The reasoning based on the First Amendment usually puts the onus on library users to argue against hate speech in books contained in the libraries. We believe that the library profession carries an obligation to use its First Amendment rights to pronounce its opinion on the subject and content of the books it offers to the public as it has done with a LOC classification system for a number of years. In the case, where such books carry incitement to genocide, the profession cannot stay silent. When such genocide is happening before our eyes, daily, and the books in the public libraries carry the message of genocide, the library must act.

In the American public libraries we advocate for (1) growth of collections of books in Ukrainian (2) strong support network for growth of circulating collection in Ukrainian with community outreach and dedicated staff (3) review of library material for proper Library of Congress classification, among others things to name the books that incite genocide.

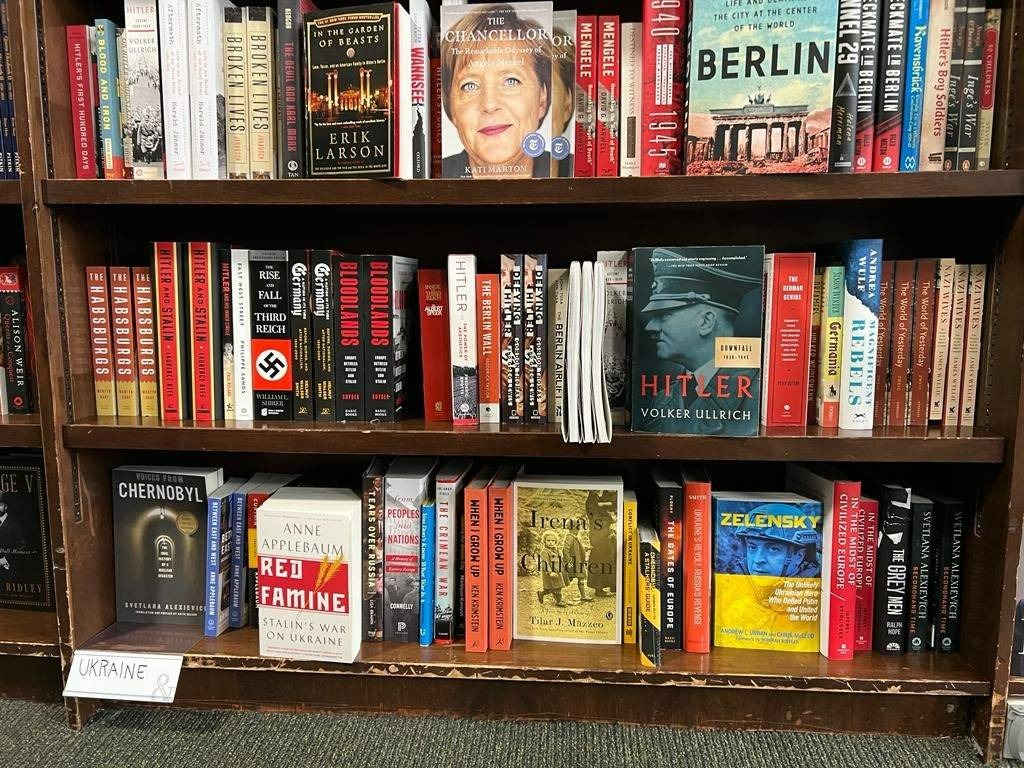

Placing books on Ukrainian history or fiction books of Ukrainian authors into “Russia” sections denies Ukraine its sovereignty and supports the formal “cause” of the war proclaimed by Russia – that Ukraine never existed. This must change. It is in the interest of American public to have comprehensive, physical access to books on Ukraine in the local bookstores. Both publishers and bookstores have their part to play.

Over the summer of 2022, we have struggled to find in physical stores a selection of Ukrainian fiction and non-fiction books to browse. Ukrainian history books appeared frequently in the “Russia” history section (we have many photos), as do frequently books on Poland and Finland.

In the largest store we have visited, one salesperson claimed that there were only twelve works of Ukrainian fiction available in English in the United States, and therefore, one available name was quite sufficient. In most other stores, salespeople have been apologetic about the lack of any physical books, offered no recommendation for online search and silently acquiesced to status quo. Only one bookseller was quick enough to point out a novel based on the events of the Maidan revolution. None of the physical bookstores (or library trade) was showing a stand with the name of “Ukraine” on the first visit. One has appeared after a correspondence lasting several months, a protest in front of corporate headquarters, a meeting and close follow ups.

In the physical bookstores, Ukraine was invisible to the American public.

Ukrainian books ended up in “Russia” or “Russia/Eastern European” section, if they are available at all. Such placement of Ukrainian books deprives Ukraine and Ukrainians their agency – something that Putin has been long trying to do with his words and now does with his weapons. How could one guess that Ukrainans fought for their land in the crucial moment of the 20th century, World War II, against the invading armies of totalitarian, dictatorial and murderous states? How one could see with the current arrangement of Ukrainian books that the majority of the Ukrainian people have fought against the Nazi regime, have suffered terrible casualties, and have made the victory of the Allies possible? The parallels between the war that Russia leads against Ukraine and World War II are very clear: Ukrainians supported by democracies around the world fight against a Nazi state that tries to erase them from Earth and openly proclaims that.

A great number of fiction and nonfiction works published by large academic and non-academic publishers offer much knowledge on Ukraine and prove that Ukrainian people will defend their land and freedom successfully. Bookstores should not stay away from Ukraine’s anti-colonial and anti-totalitarian fight. We advocate for 1) comprehensive selection of books on Ukraine and by Ukrainian authors in physical bookstores 2) convenient placement of Ukrainian books and 3) customer outreach and support to sustain the changes.

We are optimistic about the future precisely because we understand the past. Our hope rests on the the values of book industry–publishers, booksellers, and libraries. These values do not change over time and they are the values of freedom, freedom of conscience, freedom of expression, freedom of speech. Book industry should make an effort to give the freedom to the American public to hear Ukraine and its people. The voices of freedom all over the world must be heard to sustain the call sounded on the shores of the Atlantic in 1776.

Table 1. Countries or groups of countries that recognized Holodomor as genocide

| Australia | October 93 | Colombia | December 2007 |

| Estonia | October 93 | Mexico | February 2008 |

| Canada | June 2003 | Latvia | March 2008 |

| Hungary | November 2003 | Portugal | March 2017 |

| Vatican | April 2004 | USA | December 2018 |

| Lithuania | November 2005 | Czechia | April 2022 |

| Georgia | December 2005 | Brazil | April 2022 |

| Ukraine | November 2006 | Romania | 24.11.22 |

| Poland | December 2006 | Ireland | 24.11.22 |

| Paraguay | October 2007 | Moldova | 24.11.22 |

| Peru | October 2007 | Germany | 30.11.22 |

| Ecuador | October 2007 | Europarlament | 15.12.22 |

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations