According to Putin, the long existence of Ukraine as a part of Russia ensured “the common faith and cultural traditions” and “linguistic affinity,” nullifying the possibility that Ukraine could have developed its own cultural or national identity. This study tests the assumption of cultural similarities between Ukrainians and Russians by using social trust as the main framework of analysis. My point of departure is the idea that the two countries can be considered culturally similar if they have the same level of social trust and the same set of factors that determine this trust. Drawing upon this, my analysis aims to examine the extent to which the causal pattern of social trust formation in Ukraine resembles that in Russia.

Limited by confidence in strangers, social trust is often seen as a partly habituated, embodied way of engaging with others and the world. The literature broadly classifies approaches to conventional trust sources into dispositional and contextual. Dispositional theories reduce social trust to the trait of one’s character or disposition, often understood as rooted in the personality. Defined as an internal characteristic, trusting is linked to one’s psychology and emotions that give rise to faith in others by regulating the level of positive affect toward the object of trust. Seen as deeply entrenched in genetics and family, faith creation is attributed to intergenerational transmission. Collectivist ideologies, religiosity and religious beliefs are often seen as cultural settings that channel this transmission of trusting attitudes from one generation to the other.

The contextual approach relies on the premise that social trust is an action. In this view, the faith mechanism only lays the foundation for the potential creation of trust, whereas its ultimate level is determined by how this basic faith fits real-life situations created by the context. By weighing the multitude of pros and cons derived from contextual characteristics, the individuals adjust their faith in others to the actual conditions in which the trust decision is made.

Studies primarily focus on institutions when analyzing the context in relation to trusting others. The institutional approach brings forward the state and argues that the quality of formal settings in terms of just administrative procedures and honest civil servants can underpin social confidence. Recent studies suggest that, in addition to institutions, individual perceptions of inequalities within a society influence social trust by creating imbalances in interpersonal interactions. Finally, ethnic wars are expected to yield greater trust among the country’s residents when they unite against a common aggressor.

Given this wide set of social trust determinants, my analysis pursues a double objective. On one hand, I attempt to define which dispositional and contextual factors are conducive to social trust in Ukraine and Russia. On the other hand, I try to clarify whether these factors are equally important for trust formation in both countries. In doing so, I use data from the two most recent rounds (6 and 7) of the World Values Survey. The sixth round refers to 2011, whereas the seventh round corresponds to 2017 in Russia and 2020 in Ukraine. The total sample includes 4979 cases (2005 for Ukraine and 2974 for Russia).

My key dependent variable is social trust codified as a dichotomous variable that takes the value of 1 if respondents believe that “most people can be trusted” and the value of 0 if they think that “you need to be careful when dealing with people.” The independent variables were selected based on both dispositional and contextual approaches (see table 1). The dispositional set of determinants includes conventional predictors of trust, such as religiosity proxied through religion and frequency of church attendance, nationalism, health, and happiness levels.

The contextual set of predictors includes democracy, fractionalization, insecurity, and institutional confidence. Democracy is measured through the perceived quality of democracy in a country and the importance of democracy for the country’s political system. In addition, I include the attitude of respondents to free elections. Fractionalization levels are operationalized through ethnic and linguistic diversity, and beliefs about income inequality. Security is approximated by perceived security in one’s neighborhood and the war dummy. Institutional trust is captured by respondents’ trust in their government.

Given this dual nature of social trust formation, my expectations are twofold: On the one hand, I expect that both dispositional and contextual factors predict social trust in Ukraine and Russia. On the other hand, I expect that the impact of these factors is not identical in the two countries.

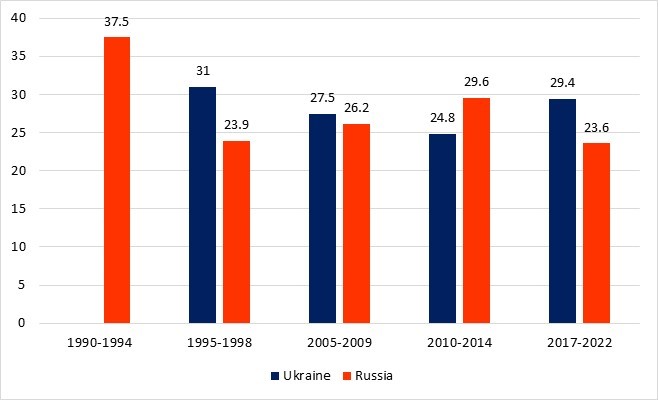

To begin with, Figure 1 shows some differences between Ukraine and Russia regarding their trust levels since the beginning of the post-communist transition. The graph demonstrates that these differences were only marginal. Both countries witnessed a decline in social trust in the 1990s. However, unlike Russia, Ukraine managed to restore the initial trust levels after the Euromaidan, which is captured by the 2020 survey.

Figure 1. Change in percentage of people who trust others: Ukraine versus Russia

Notes: Figure 1 compares mean values of social trust between Ukraine and Russia for each WVS round in which the two countries participated.

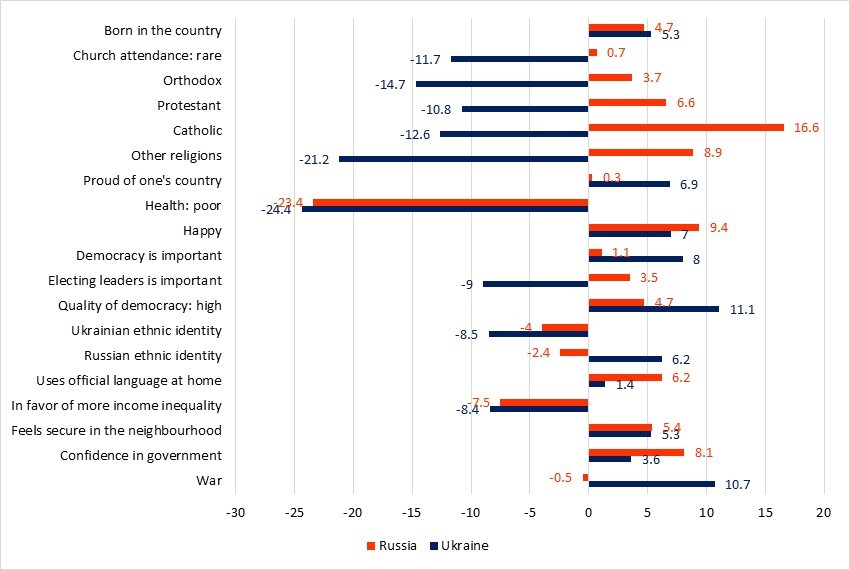

Table 2 and Figure 2 suggest that significant contrasts between the two countries exist in the pattern of social formation. The differences are seen between both contextual variables and dispositional predictors, such as religion. Even if people adhered to the same religion and possessed close levels of religiosity in both countries, the impact of religion and religiosity on social trust appeared to significantly differ between Ukraine and Russia. Religious individuals were more likely to trust others in Ukraine (in particular, attending church on a weekly basis increased the likelihood of trusting others by 11.7 percentage points) but showed no significant difference from non-religious respondents in Russia.

Figure 2. Average marginal probability of social trust: Ukraine versus Russia

Notes: Logistic regression is used to calculate the coefficients. The coefficients show a percentage change in the probability of trusting if the corresponding variable changes its values from 0 to 1.

Likewise, individuals who adhered to the Orthodox religion were characterized by lower levels of trust in Ukraine but tended to trust slightly more in Russia (-14.7 p.p. vs. 3.7 p.p.). Health and happiness levels similarly influenced social trust formation in both countries: being happy increased trust, while health problems lowered it. Important differences between Ukraine and Russia are observed with respect to nationalism (measured as being proud of one’s country). This factor increases the likelihood of trusting by 6.9 percentage points in Ukraine, but is practically zero (and insignificant) in Russia. Thus, national pride is more important in bonding individuals in Ukrainian society than in Russia.

A similar pattern was found for democracy-related variables. Although both societies had relatively similar self-reported scores on the quality of democracy, this variable had a positive (+11.1 p.p.) impact on social trust in Ukraine and showed no association with trust formation in Russia. A significant difference also emerged in the value respondents assigned to democracy as a form of governance in their country. Individuals who believed that democracy is essential for a good political system were 8.0 percentage points more likely to trust others in Ukraine, but not in Russia. At the same time, the importance of free elections was not robustly associated with trust levels in either country.

Of the selected fractionalization predictors, only the attitude to income inequality had an impact on social trust. An inclination toward an economically egalitarian society could increase the likelihood of trusting by 8.4 percentage points in Ukraine and 7.5 percentage points in Russia. Language use was not related to social trust in either country. At the same time, ethnic self-identification was marginally associated with trust scores in Ukraine but not in Russia. Ukrainian residents who identified themselves with the Russian nation had a higher likelihood of trusting than individuals who did not. This suggests that the Russian minority was well-integrated into Ukrainian society.

The war variable was a positive and statistically significant determinant of trust levels in Ukraine but not in Russia suggesting that the war unified Ukrainians against the enemy. Instead, confidence in government positively influenced social trust among Russian people, increasing their likelihood of trusting by 8.1 percentage points. For Ukraine this factor is insignificant. A tentative explanation can be that in Ukraine people tend to differentiate government from the country (including peer citizens), which is more in line with the democratic tradition.

Both societies viewed security in neighborhoods as a foundation for trust formation. Changing from feeling insecure to secure could increase the likelihood of trusting others by approximately five percentage points. Finally, there was wide variation in trust levels across Ukraine’s regions, which can be justified by the country’s historical specificities of territorial formation and unequal distribution of Russian-speaking minorities across the country. The unequal economic and social development of regions may also explain the cross-regional variation of trust in Ukraine. In contrast, Russia’s society was more homogenous in terms of trust, even though some marginal regional differences could also be observed.

Overall, estimation results suggest that even if the two countries considerably resemble each other in their cultural, economic, and contextual characteristics, many of them played very different roles in yielding greater trust. These differences can broadly be summarized in four key points.

First, social trust formation patterns differed significantly between Ukraine and Russia in terms of their major sources. In Ukraine, unlike in Russia, trust was, to a larger extent, the result of contextual factors. Russians primarily relied on their dispositional characteristics to define their level of confidence. This suggests that social trust took the form of faith in Russia, while it was a result of experiences with the country’s context in Ukraine.

Second, among the contextual characteristics, Ukraine stood out in the role of democracy-related factors in shaping trusting attitudes. Both the actual quality of democracy and aspirations for democracy as a form of governance significantly defined trust levels. In contrast, Russians’ social trust was largely shaped by two contextual factors directly related to their imperial identity, such as trust in the government and security issues. The idea of a “great” country not only requires from the individuals a strong attachment to the state and the fear of constant danger but also essentially influences social trust. Those who trusted the government and felt protected by the state displayed greater confidence in their fellows.

Third, despite the established similarities in many cultural factors, such as religion and religiosity, Ukraine significantly differed from Russia in how these factors influenced confidence in society. For Ukraine, the data confirmed existing patterns regarding how the relevant variables affect the formation of social trust (i.e. people associating themselves with a religious group trust less than atheists but those attending church more often trust more). In contrast, in Russia both religion and religiosity showed a relationship to trust levels opposite to the existing theories.

Fourth, the conflict in eastern Ukraine had a strong positive impact on social trust. The war united Ukrainians in the face of a common aggressor. In Russia, the war did not play a substantial role in yielding greater trust among individuals. Instead, greater confidence in the government arising from Russians’ imperial visions united the country’s population.

In summary, my comparative analysis between Ukraine and Russia using social trust suggests that the Kremlin’s assumption that race, religion, and language are critical markers for drawing similarities between our nations should be perceived as false. Even though Ukrainians and Russians had the same religion and ethnicity, and many of them spoke the same language, they developed different trusting attitudes and patterns of trust formation. Thus, my results highlight the existence of a wide gap between the two populations, suggesting that they are two separate nations (here I define a nation as a political and social entity). It is not only the language and religion that make a nation but the way in which people act within the given religious and linguistic settings that make these people a distinct nation.

In Russia, social relations are shaped by the imperial visions of the population. The idea of a strong state constitutes a central point in this imperialist ideology that has significantly impacted contemporary Russian society. Russian citizens are united into society through their attachment to the government and low significance attributed to democratic values (the right to own property, freedom of speech, freedom of conscience, etc.), which results in the limited role these values play in shaping social relations. Social trust takes the form of faith, with the Orthodox religion only reinforcing people’s connection to the state. The strong ideological interdependence between religion and the state is used in Russia as an important symbol of local history and tradition for nurturing the feeling of belonging to the nation and society.

In contrast, social relations follow an entirely different mode of formation in Ukraine. Despite the shared past with Russia, the idea of the state had only an indirect influence on uniting the population by creating democratic institutions in the country. The aspiration for democracy directly arose from the opposition to the idea of a dominant state, often interpreted through the country’s long experience as a colony, occupied by the Russian empire and its descendant Soviet Union. The church’s independence from politics further promoted free thinking in Ukraine and an ultimate departure from the soviet legacy. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrated to Ukrainians the importance of political unity, created by bonding people through mutual aspirations about their own nation and country.

Table 1. Representation of independent variables

| Variables | Scale | Response values |

| Dispositional | ||

| frequency of church attendance | a seven-point scale with values from 1 to 7 recoded to change between 0 and 1 | 0 = “more than once a week” to 1 = “never” |

| religion | – | Catholic, Protestant, Orthodox, other |

| nationalism | binary | 0 = “not proud for my country”; 1 = “proud for my country” |

| health | five-point scale | from 1 = “very good health” to 5 = ”very poor health” |

| happiness level | binary | 0 = “not really happy”; 1 = “quite happy” |

| Contextual | ||

| perceived quality of democracy in a country | ten-point scale with values from 1 to 10 recoded to change between 0 and 1 | 0 = “not at all democratic” to 1 = “completely democratic” |

| importance of democracy | binary | 0 = “democracy is not at all important”; 1 = “democracy is important” |

| attitude to free elections | binary | 0 = “people should not choose their leader in free elections”; 1 = “people should choose their leader in free elections” |

| ethnic group | binary | Ukrainian (for Ukraine)/ Russian (for Russia), other |

| language spoken at home | – | Ukrainian, Russian, other |

| belief about income inequality | ten-point scale with values from 1 to 10 recoded to change between 0 and 1 | 0 = “incomes should be made more equal” to 1 = “we need larger income differences as incentives” |

| security in one’s neighborhood | binary | 0 = “not really secure”; 1 = “very secure” |

| war | binary | 0 = “responses correspond to the pre-war period (2011)”; 1 = “responses correspond to the war period (2020) |

| trust in the national government | binary | 0 = “no confidence” and 1 = “great confidence” |

Note: “Other” category in the “religion” variable includes only 1.5% of respondents

Table 2: Key Factors behind Social Trust Formation in Ukraine and Russia

| Variables | Ukraine | Russia |

| Born in the country | 0.053 | 0.047 |

| (0.050) | (0.039) | |

| Age | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Church Attendance | -0.117** | 0.007* |

| (0.047) | (0.004) | |

| Religion types | ||

| Atheist | Ref. category | Ref. category |

| Orthodox | -0.147*** | 0.037* |

| (0.036) | (0.020) | |

| Protestant | -0.108 | 0.066 |

| (0.086) | (0.094) | |

| Catholic | -0.126** | 0.166 |

| (0.053) | (0.138) | |

| Other | -0.212*** | 0.089 |

| (0.072) | (0.081) | |

| Nationalism | 0.069*** | 0.003 |

| (0.026) | (0.025) | |

| Health | -0.244*** | -0.234*** |

| (0.073) | (0.063) | |

| Happy | 0.070*** | 0.094*** |

| (0.026) | (0.023) | |

| Democracy Value | 0.080*** | 0.011 |

| (0.020) | (0.018) | |

| Chooses Leader in Elections | -0.090* | 0.035 |

| (0.047) | (0.036) | |

| Democracy Evaluation | 0.111*** | 0.047 |

| (0.041) | (0.038) | |

| Ukrainian Ethnic Identity | -0.085** | |

| (0.040) | ||

| Russian Ethnic Identity | -0.024 | |

| (0.042) | ||

| Other Ethnic Identity | Ref. category | Ref. category |

| Uses Official Language at Home | 0.014 | 0.062 |

| (0.027) | (0.041) | |

| Uses Other Language to Communicate at Home | Ref. category | Ref. category |

| Income Inequality | -0.084** | -0.075** |

| (0.039) | (0.030) | |

| Feels Secure | 0.053** | 0.054*** |

| (0.026) | (0.018) | |

| Confidence in the Government | 0.036 | 0.081*** |

| (0.023) | (0.016) | |

| War | 0.107*** | -0.005 |

| (0.024) | (0.041) | |

| Regions (UA) | ||

| East | Ref. category | |

| West | -0.120*** | |

| (0.039) | ||

| South | -0.134*** | |

| (0.031) | ||

| Center | -0.111*** | |

| (0.035) | ||

| Kiev | -0.088** | |

| (0.038) | ||

| Regions (Russia) | ||

| Moscow | Ref. category | |

| North West | 0.035 | |

| (0.049) | ||

| Central | 0.027 | |

| (0.044) | ||

| North Caucasian | -0.096 | |

| (0.080) | ||

| Privolzhsky | 0.092** | |

| (0.043) | ||

| Urals | 0.019 | |

| (0.049) | ||

| Far East | 0.099* | |

| (0.057) | ||

| Siberian | -0.006 | |

| (0.046) | ||

| South | 0.110** | |

| (0.045) | ||

| Log-likelihood | -1151.713 | -1627.124 |

| Observations | 2,005 | 2,974 |

Source: Author’s calculations using the WVS (2011, 2017, and 2020).

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations