While agriculture has been a net recipient of subsidies, current measures fail to achieve the objective of enhancing productivity and compensating for market failures because they were largely poorly designed, fragmented, ad hoc, ill targeted and not pro-growth. Based on global principles for such support, we discuss specific options for redressing this and outline next steps to be taken in this respect.

Guiding principles in designing efficient agricultural support policies

Over the last century, there has been extensive stock of research and analysis on agricultural support. OECD nicely converts this stock of knowledge, including their own extensive experience, into clear policy recommendations. They are very much aligned with the WTO framework on domestic support measures in agriculture, whereby various support measures are grouped into those subject to restrictions – trade-distorting support (or ‘amber box’ measures) and those not subject to restrictions – with no or minimal distortive effect on trade (‘green box’ measures). Building upon this stock of knowledge and taking into account Ukraine’s political economy/reform content, we explore Ukraine’s agricultural support measures against the following guiding principles:

Do not pick up the winners – products/sectors

If a government explicitly supports a particular sector with subsidies, this implies the government can correctly pick up the right sectors and correctly foresee their future and contribution to the overall economic development. Formally speaking this is so-called infant industry promotion policy. There are, however, two strong arguments against this industrial policy:

- it is an illusion that a government is in the best position to identify correct industries, products and firms to support, since this requires deep knowledge of the markets and technological processes; this is especially a problem for developing and transition countries where analytical capacity of governments is very limited;

- in selecting winners, government may be influenced by bribes and lobbying, which generate big distortions and lead to market inefficiencies. Creating top-down list of sectors that require the government support proved to be counterproductive. Instead, it is much better to create an environment where all types of companies in all sorts of industries are able to produce and experiment with different products. The markets will then select good and bad products without any government involvement.

This approach is very much in line with the WTO framework that restricts so-called coupled support, i.e. the one linked to supporting specific sectors and products.

Focus on market failures

There are many cases, however, when governmental intervention is well justified and desirable, i.e. in case of market failures, when market cannot provide adequate signals. They include all kinds of negative externalities (e.g. environmental problems, climate change). Positive externalities in the form of public goods and services is also a well justified excuse for government intervention, in particular they extend the benefits to all producers. For example, building up the roads, a modern and efficient plant and animal health and food safety systems, efficient land governance infrastructure, information systems, education, research and development, extension services etc. These are all services that benefit all producers but the private sector is not able to supply a sufficient level of public goods output.

Market imperfections is another case of a market failure. Imperfect financial (credit) markets is perhaps a common one for developing and transition countries. In Ukraine this is magnified by the land sales moratorium, whereby especially small and to some extend medium agricultural producers have no access to credits. This precludes small farmers from making productive investments, increasing their productivity and grabbing higher market shares and incomes.

WTO domestic support framework does not restrict its members in expenditures on such activities, which all fall into the green box category of domestic support measures. So implicitly WTO nudges its members to shift support measures from amber to green box measures.

Consider fiscal constraints and targeting

Counties very often face fiscal constraints. This is especially so for countries like Ukraine with its difficult fiscal and macroeconomic situation, significant budget deficit and war in the East. In these circumstances agricultural fiscal support budget is expected to be quite limited and it is important to design farm-income support measures targeting those in a real need.

Agricultural Fiscal Support in Ukraine

Evolving structure of a fiscal agricultural support

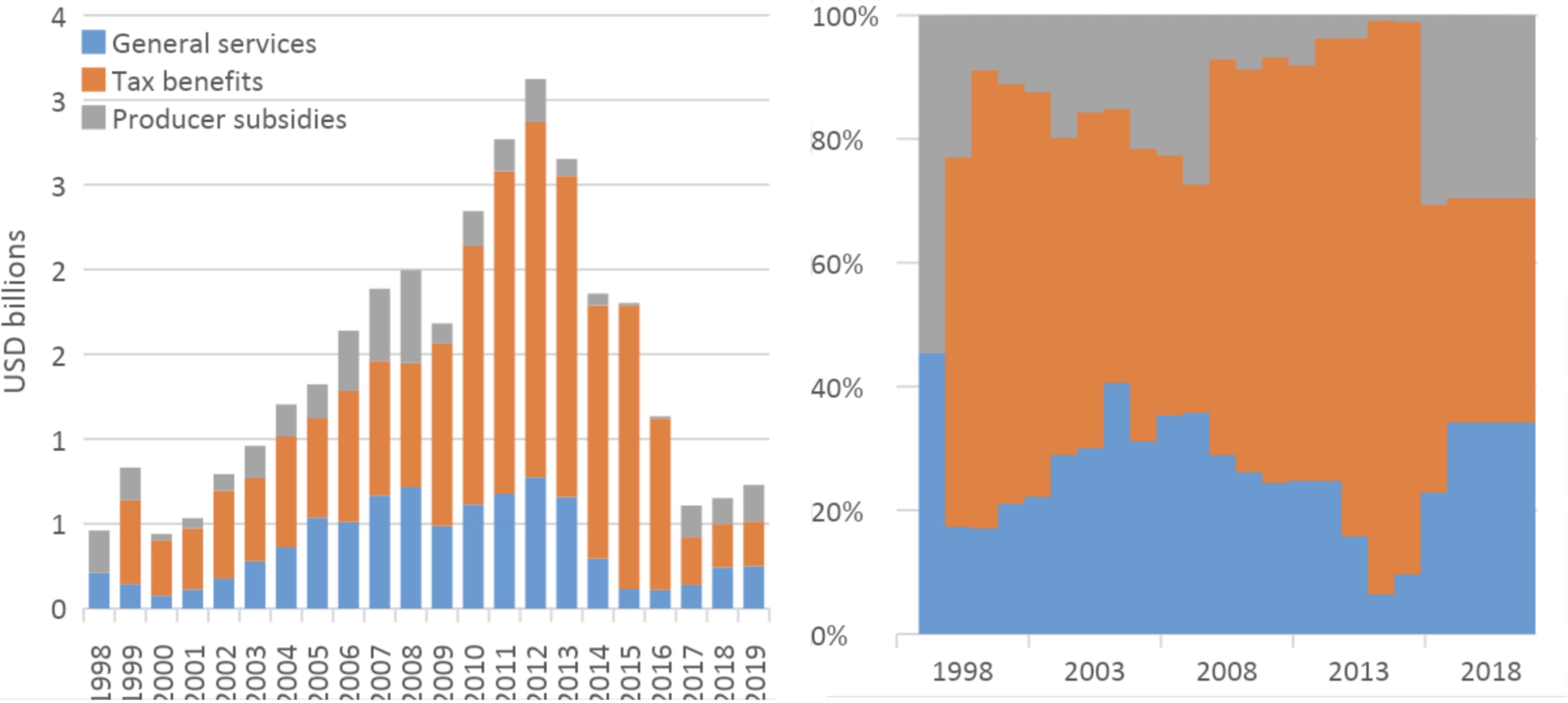

Before 2017 tax benefits was the major source of a fiscal support to agriculture (Figure 1). Support of general services in agriculture (e.g. sanitary and phytosanitary measures, education and research, food security, extension services etc) or so called ‘green box’ measures (according to the WTO classification) was a second major component of agricultural fiscal support. The weight of direct producers’ subsidies (direct budget outlays to producers) has always been the lowest. Tax benefits accrued from a so-called single tax (or Fixed Agricultural Tax before 2015 – FAT) and a special value-added tax regime in agriculture – AgVAT.

Figure 1. Agricultural fiscal support in Ukraine since 1998

Source: own presentation based on PSE ОЕСD tables and State Budgets of 2018 and 2019 years

The FAT is a flat rate tax that replaced profit and land taxes. Its rate varies from 0.09% to 1.00% of the normative value of farmland. In 2010, the FAT resulted in an average tax payment of only roughly USD 0.75/ha of arable land that left farm profits in Ukraine essentially untaxed. In 2015, due to significant increase of the normative value of land, FAT liabilities increased to roughly USD 9/ha, which is also very low compared to what the farmers would have paid on the general tax system.

According to the AgVAT regime, farmers were entitled to retain the VAT received from their sales to recover VAT on inputs and for other production purposes at the discretion of farmers. In 2016 and 2017 the AgVAT system was gradually eliminated under the IMF and other international donors pressure. In 2015, the benefits from the AgVAT were estimated at UAH 28 bn. The FAT or profit tax exemption is still in place and is expected to continue.

In 2017 the AgVAT tax benefit system was terminated and replaced by so-called ‘quasi accumulation VAT’ regime. This was no longer a tax benefit system, but instead agricultural producers (mainly livestock and horticulture producers) were entitled to receive budget subsidies proportionally to the VAT transferred to the state budget. The total volume of the program was UAH 4 billion. The program was, though, heavily criticized as such that favored primarily large agriholdings and thus was terminated.

Current farm subsidies programs

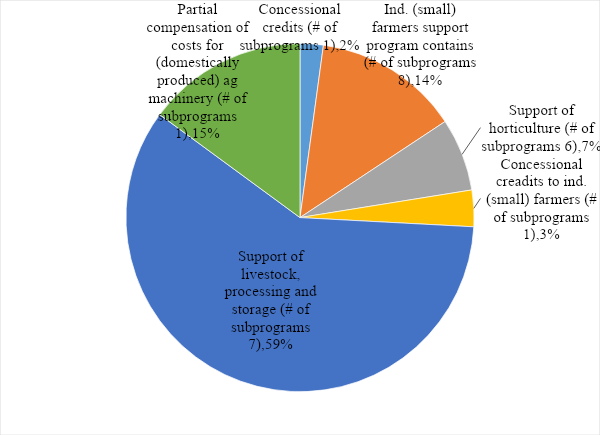

Since 2018 the volume of producer subsidies significantly increased and their structure also changed substantially. Broadly speaking now all producer subsidies fall into 5 major programs: 1) concessional credits; 2) individual farmers support; 3) support of horticulture; 4) support of livestock, processing and storage; 5) partial compensation of costs of (domestically produced) agricultural machinery. Each of these categories contains another 1 to 8 subprograms (see Table 1 in the ANNEX for the detailed description of the programs):

- concessional credits: the program compensates 50 to 100% of the refinance rate of the National Bank of Ukraine to all eligible agricultural producers. Producers of livestock products are treated more preferably;

- individual farmers support program contains 8 + 1 subprograms, whereby individual farmers can get support for: concessional credits, 80% compensation of costs of seeds, 90% compensation of extension services costs, financial support of cooperatives, compensation of agricultural machinery costs, per ha subsidy for new and existing individual farms. Additional program foresees interest-free credits for working capital, production and processing, construction etc;

- support of horticulture program contains 6 subprograms, whereby agricultural producers receive a partial compensation of costs of: planting material for fruit and berries crops, vineyards and hops; cooling equipment; processing lines; refrigerating equipment; drying equipment; other specialized machinery;

- support of livestock, processing and storage program includes 7 subprograms: concessional credits; partial compensation of the cost for construction or reconstruction of livestock farms, milking parlors or processing facilities; maintaining or increasing the herd of young cattle (per head); per cow head payments for corporate enterprises; partial reimbursement of costs of breeding livestock; partial compensation of the cost of construction of grain storage and processing;

- partial compensation of costs of (domestically produced) agricultural machinery, whereby agricultural producers can get up to 25% compensation of agri-machinery costs.

Figure 2. Composition and weight of various farm support programs

Source: own presentation using Treasury data

So, in one way or another, the above programs could be summarized as so-called input subsidies, i.e. subsidies that decrease the costs of inputs for the farmers.

Analyzing Agricultural Fiscal Support Measures

Agriculture is a net recipient of a fiscal support

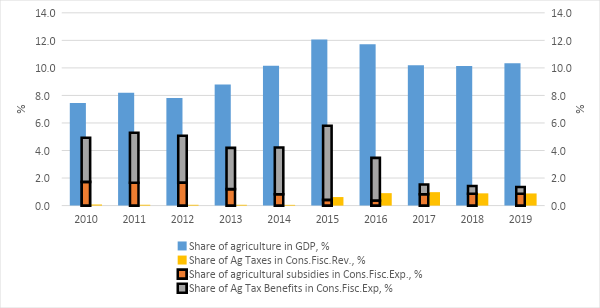

While agriculture has been one of the most successful and growing sectors in Ukraine, agricultural producers remain net recipients of fiscal support. Figure 2 below demonstrates that tax benefits (forgone fiscal revenue which is a subsidy) and agricultural subsidies (direct producer subsidies plus expenditures on general services) in total exceed the volume of tax revenues generated/paid by agricultural producers. We do not account for the revenues from the value added tax (VAT) as well as from the personal income tax (PIT) in agriculture, for these taxes are de-facto paid by either consumers (in case of VAT) or by employees/landowners (in case of PIT) and producers play the role of tax agents only. As it was mentioned above, profits are not taxed in agriculture, but instead a low flat rate tax FAT is levied.

Figure 3. Contribution of agriculture to national economy and to the State Budget of Ukraine, %

Source: own presentation based on Ukrstat and Treasury data; Cons.Fisc.Rev. – consolidated fiscal revenues; Cons.Fisc.Exp. – consolidated fiscal expenditures.

Ad-hoc and poor design/implementation without incremental effect on investments and productivity

To start with there is no officially approved Strategy for Agricultural and Rural Development in Ukraine, which implies a lack of officially declared long-term vision and measurable goals that the state support or budget program KPIs could be aligned with.

As a consequence, a design of agricultural support programs has been ad-hoc, without a due public and evidence-based discussion and it was subject to repeated changes over the last several years. Budgeting and implementation of the programs also has been ad-hoc. Overall level of budget programs execution and its timing remains substantially ad-hoc, 92% of the planned outlays were disbursed in 2017 and only 66% in 2018. Moreover, only about 20% of the planned budget outlays were disbursed by the fall last year. This implies the government subsidized investments and purchases that would have made in any case. In order to be effective and to have incremental effect on productivity/output or to change the behavior of producers, budget support programs have to be stable and lasting for a long time so that agricultural producers could develop a trust and include them into their business plans. In other words, one always has to ask a question whether investments, for instance, in a construction of livestock complexes would have been possible without the subsidies. If such investments were not possible without subsidies, then these subsidies could be regarded as effective, putting aside a question of their economic effect.

Poor design has also been a part of the story. For example, there are three credit concession programs (see Table 1) tailored to different various farm groups with a total budget of about USD 10 mln in 2019. A fundamental flaw of this program is that a decision about the subsidy (compensation of the interest payments) is made by a special commission (nominated by the MAPFU) post factum, i.e. after a decision by the bank on the extension of the credit has already been made. In other words, by applying to the bank for the credit, a farmer does not know whether interest payment will be compensated/or what share of interest payments will be compensated. As a result the program becomes irrelevant with respect to increasing the volume of agricultural credits.

The same flaw is contained in other major support programs – partial compensation of the cost for construction or reconstruction of livestock farms (USD 33 mln in 2019) and partial compensation of agricultural machinery costs (USD 35 mln in 2019). In each case a decision on subsidy is made post-factum, i.e. after a reconstruction and corresponding expenses have been made or after an ag machinery has been purchased already.

All the budget support programs are designed in a way that a compensation of input costs is undertaken post factum, i.e. after the decision ‘to invest or not’ is made. Also there is always a ministerial commission on a way to the subsidy which increases uncertainty of getting the subsidy and increases the risk of corruption.

In such circumstances and taking into account a historical distrust among the farmers to budget support programs, one can rather strongly argue that current investments in agriculture (gardens, machinery, seeds, credit etc.) are made irrespective of subsidies and would have been made in any case. So current subsidies cannot be considered as effective.

Fragmented design that thus dilutes public resources and increases administrative costs

So far there are too many budget agricultural support programs (i.e. 24) which dilutes the effectiveness of each of the programs (taking into account limited fiscal resources available for agriculture) and does not address market failures. Apparently this stems from a lack of clearly defined goals of agricultural development and makes an impression that policy makers are trying to tackle a little bit of everything. Fragmented design of the support programs results in:

- Overlapping responsibilities: a clear example is the existence of 3 credit concession programs;

- Conflicting goals: agro machinery costs compensation program is specifically tailored for domestically produced agro machinery which is not necessary in line with increasing agricultural productivity goal. Domestically produced agricultural machinery is often cheaper but of inferior quality/lower productivity compared to the imported one.

- Increased administrative costs: running more than 20 individual support programs certainly requires individual administration and thus increases total costs of administering state fiscal support programs.

Concentrated and ill-targeted design of the support programs

Only about 15% of the budget support is channeled specifically to small farmers, although this share is further diluted among 8 various support subprograms with all consequences we raised in a previous section.

Other support programs are designed in a way that benefits primarily medium and especially large agricultural enterprises. Each year two to three large agricultural companies receive more than a half of total subsidies, and huge scandal outbursts in the local and international media outlets.

Credit concession programs are accessible only to those farms that already have an access to commercial banks lending. Mostly these are the farms larger than 2,000 ha. Smaller farms (lower than 500 ha size or even below 100 ha) usually do not have access to commercial credits. As a consequence, only a meager share of credit concession subsidies end up with small farmers. The same story line applies to other major program. Investments in agricultural machinery, livestock complexes or processing facilities/lines is by definition easier and faster for medium and large agribusiness (including due to better access to capital) which implies better and to a greater extent in higher volumes access to state subsidies.

Mounting distortions

Even if all the above problems were gone and everything functioned properly (i.e. clearly defined strategy and development goals, minimum necessary programs, appropriate targeting, timely and transparent design and implementation, no risks of corruption, demonstrated effectiveness etc), still a question about the appropriateness of the support instrument (input subsidies) would remain. Just to remind, in one way or another, all the fiscal support measures could be summarized as so-called input subsidies, i.e. subsidies that decrease the costs of inputs for the farmers.

It is widely accepted in policy making and economics is that a good policy should aim at no or minimum distortion of economic signals. WTO classification of agricultural support measures explicitly points out which measures distort (amber box measures) and which don’t (green box measures). Input subsidies in their current form are to a great extent tailored for specific sectors/products thus distort production structure of agricultural sector by favoring some sectors and ignoring the others.

Poor instruments for achieving higher growth

Improving competitiveness and productivity are the two measures associated with growth and are usually the main goals of agricultural policy. There there are absolutely good reasons for that, especially for Ukraine. First of all, current agricultural productivity in Ukraine is a fraction of that in other European countries. Agriculture value added per hectare in 2016 was $416 in Ukraine, compared to $1,414 in USA, $1,266 in Brazil, $773 in Argentina, $527 in Russia and $2,239 in France. The primary reason for this is that agricultural production in Ukraine focuses on lower value-added products (such as grains). Another reason is that the terms of trade for farmers is deteriorating, i.e. the ratio of farms output to inputs prices is decreasing over the last 6 years. In other words, prices for farm inputs are rising faster than prices for agricultural products. Accordingly, the only sustainable way for farmers to maintain or increase their incomes is to increase productivity.

Documented evidence so far gives a pretty clear guidance on whether coupled support/input subsidies stimulate productivity and efficiency gains in the agricultural sector. Existing empirical studies demonstrate that so-called “coupled” subsidies (including input subsidies) have a major adverse effect on production efficiency and productivity. From a scientific and also practical point of view, we have a competing forces of income and substitution effects here. The income effect is that farmers can buy more machinery, for instance, or it is cheaper for them to buy the same number of machinery that can improve their productivity. At the same time, it can lead to the so-called soft budget constraints, whereby farmers will invest too much without real economic need. An extreme example would be Switzerland with the highest tractor intensity in the world. United States, for example, have almost ten times fewer tractors per 10 ha. Furthermore, the substitution effect opposes the income effect because managers may work less hard to achieve a certain level of profitability/efficiency because of the subsidy. Empirical evidence suggests that the substitution effect almost always prevails. An example of the EU, with its heavy support programs and where farming turned more into a hobby than a business, is a clear evidence to that.

Unintended beneficiaries

Transfer efficiency studies of support programs suggest that the major and ultimate beneficiary of input subsidies are input suppliers, – more that 80% of the entire state support ends up in the pockets of inputs suppliers in one way or another. Input subsidies also imply significant dead-weight losses – 5-6% of the state support. This is especially evident in case of the program that compensates the costs of domestically produced agricultural machinery. It is widely regarded as a subsidy to domestic producers of agricultural machinery rather than to farmers (we mentioned already a conflict of interest in the case of this program above).

Some positive developments achieved and to be kept and developed further in the future

There are, however, some positive developments with agricultural fiscal support that are important to keep in the following phases of its reform – clear focus on more transparency. One has to acknowledge a new webpage of the Ministry of Agricultural Policy and Food dedicated to explaining various modalities of the agricultural fiscal support programs. Also one can find there quite detail reports on who received the support and in what amounts.

How to Achieve Higher Effectiveness with the Current Support Budget?

Following the storyline we developed in previous sections, It may be useful to discuss these in a bit more detail (i.e. we do not want to pick winners but (i) efficiently provide public goods (e.g. extension, markets, irrigation, environmental management); (ii) overcome market imperfections (credit markets being the most immediate one) that were reinforced by the land sales moratorium; and (iii) ensure a level playing field and basic equity which implies providing opportunities for viable small farmers to invest.

Abandon current sector/product specific programs

Aim at shifting as much as possible to so called green box measures (according to WTO classification): pest and disease control, developing rural infrastructure, land governance infrastructure, agricultural training/education and research, general inspection services etc.

Design a targeted farm support instruments to tackle a specific market failure

Access to finance is the immediate market failure that the farmers face. The reason is fairly objective and economic in nature – there are significant risks on the banks’ side when working with farmers because of usually no collateral, lack of bank-friendly financial reporting (because of a simplified system of taxation and reporting for agricultural sector), lack of credit history or information asymmetry etc. This problem is reinforced by existing agricultural land sales moratorium that has been in place since 2001 and does not allow farmers use their land as a collateral. This is especially a problem for small farmers that usually cultivate their own land.

A proposed new design includes the following components:

- Small and medium farmers is a target of the new fiscal support model

Large farmers are already getting disproportionately higher volumes of support via tax benefits from the single tax.

- Basic extension voucher for a target group

This would include developing state/private extension service providers that would reach out with messages on production as well as economics/finance, potentially with co-payment being phased in/increased over areas. The Government have to work on accrediting extension service providers and framing the messages

- Improve access to finance for a target group

Partial or Full Guarantee Fund (PCG) is well recognized instrument to tackle this problem and is considered one of the most market friendly intervention. It guarantees fully or partially the repayment of loans in the case of a default. This reduces the risk of lending for banks and creates a multiplier effect on the volume of lending to the agricultural sector. Roughly speaking, if the share of non-performing loans in the agricultural sector is currently around 6%, with 100% guarantee, the UAH 7 billion currently allocated to subsidies to farmers could be converted to more than UAH 50 billion of credits under the guarantee of the Fund. The multiplier, based on international experience, can be as high as 20. Of course, it is necessary to discuss separately the design of such a Fund, the conditions of access to the Fund’s resources, its formation and independent functioning of the Supervisory Board, etc.

- Capitalize the small farm sector through targeted support

On top of PCG, the government can design a subsidy program for a target group that could be embedded into the PCG facility. Matching grants and to a less extend interest rate subsidies could be two alternative instruments.

Matching grants up to a certain predefined cap per producer for acquisition of a set of inputs (machinery, simple construction, sprinkler irrigation etc) could be used to capitalize small farms and increase their productivity.

Interest rate subsidies could be another alternative and there is a way to make this instrument working properly. There are, however, enough investment opportunities with returns high enough to pay market interest rates and generally speaking we do not these to be crowded out by low-return investments.

- Ensure minimum intervention of the government in selecting the recipients of the support

This is a condition to avoid rent seeking and corruption. A new design should aim at involving private sector and commercial banks in particular in selecting good candidates for a support.

- Stringent monitoring and transparency of subsidies distribution

Current shift of the Ministry towards more transparency of subsidies’ distribution should be highly welcomed and maintained. A farmer registry could substantially improve administration, transparency and accountability in this area.

Annex

Table 1 Farm support programs

| Concessional credits (# of subprograms 1) | 5.03 |

| Concessional credits to all agricultural producers in local currency | 5.03 |

| Ind. (small) farmers support program contains (# of subprograms 8) | 31.62 |

| compensation of costs of seed | 3.16 |

| compensation of extension services costs | 0.20 |

| financial support of cooperatives | 1.98 |

| compensation of agricultural machinery and equipment costs | 9.88 |

| per ha subsidy for new farm | 3.55 |

| per ha subsidy for existing individual farms | 9.48 |

| concessional credits | 3.36 |

| credit arrears compensation | 0.01 |

| Support of horticulture (# of subprograms 6) | 15.81 |

| partial compensation of costs of: planting material for fruit and berries crops, vineyards and hops | 7.91 |

| cooling equipment | 5.93 |

| processing lines for fruits | 0.48 |

| refrigerating equipment for fruits and berries | 1.00 |

| other specialized machinery | 0.27 |

| drying equipment for fruits | 0.23 |

| Concessional credits to ind. (small) farmers (# of subprograms 1) | 7.91 |

| Concessional credits for ag machinery, equipment, working capital, processing, certification, planting fruits and berries, cooperation development, irrigation etc | 7.91 |

| Support of livestock, processing and storage (# of subprograms 7) | 138.34 |

| concessional credits for sheep, goats, bees, beast, rabbit and fish sectors | 1.98 |

| partial compensation of the cost for construction or reconstruction of livestock farms (on bank credits) | 3.95 |

| per cow head payments for corporate enterprises | 27.67 |

| maintaining or increasing the herd of young cattle (per head) | 27.67 |

| partial reimbursement of costs of breeding livestock | 9.88 |

| partial compensation of the cost for construction or reconstruction of livestock farms | 33.60 |

| partial compensation of the cost of construction of grain storage and processing | 33.60 |

| Partial compensation of costs for (domestically produced) ag machinery (# of subprograms 1) | 34.85 |

| Partial compensation of ag machinery costs | 26.95 |

| other expenditures | 7.91 |

| TOTAL | 233.56 |

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations