Ukraine committed to aligning its legislation with European environmental standards as part of its Association Agreement with the EU. However, the ongoing war with Russia has made fulfilling this promise significantly more difficult. The Russian invasion has caused severe damage to Ukraine’s ecosystems, with 23% of the country’s territory (139,000 square kilometers) potentially contaminated by landmines. In addition, funding for environmental protection programs has decreased, and constant shelling has destroyed parts of the country’s ecological monitoring infrastructure.

Despite these challenges, Ukraine continues to work on building its capacity for environmental protection. In recent years, the government has succeeded in updating legislation on waste management, industrial pollution control, and access to environmental information.

Before Ukraine’s active move toward European integration, environmental policy had remained mainly outside the government’s focus, and much of the legal framework relied on outdated Soviet-era approaches. Early reform efforts were sporadic and lacked a systematic approach. With the signing of the EU Association Agreement, Ukraine gained a clear direction and binding commitments that have served as a roadmap for aligning our national laws with EU standards.

Chapter Six of the EU–Ukraine Association Agreement—Environment—contains the key environmental integration provisions. According to Annex XXX, Ukraine is required to implement 26 EU directives and three regulations covering air and water quality, waste management, nature conservation, climate change, and industrial pollution.

Figure 1: Areas of implementation of European directives

Clean air

Directive 2008/50/EC on ambient air quality is the key piece of EU legislation in this area. It sets limit values for concentrations of pollutants in the air, including particulate matter (PM10, PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and ozone (O₃). The directive requires mandatory air quality monitoring in cities and industrial areas and the development of air quality plans if pollutant levels exceed the limits.

For Ukraine, this means implementing a modern air monitoring system, designating low-emission zones in major cities (where local authorities may, for example, restrict vehicle access to reduce pollution), and enforcing stricter controls on industrial facilities and thermal power plants (TPPs). These efforts are expected to help reduce respiratory illnesses among Ukrainians.

What has been done so far? To improve air quality, the government has adopted regulations on how air monitoring should be conducted. The Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources (Ministry of Environment) oversees the entire process. At the same time, the State Emergency Service, the Ministry of Health, the Ukrainian Hydrometeorological Center, local authorities, and businesses are responsible for setting up monitoring stations. These stations measure levels of sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, dust, and other pollutants, as well as meteorological indicators. The Ministry of Environment collects this data, publishes it via the national open data portal, and uses it to assess air quality, develop policies, inform the public, and meet international reporting requirements.

In 2023, the Ministry of Environment published methodological guidelines for developing air quality improvement plans. Local communities are expected to appoint a coordinator for the plan and form working groups, including representatives from the Ministry, local authorities, the State Emergency Service, the Ministry of Health, environmental initiatives, academic institutions, and businesses. These groups will monitor air pollution levels and develop recommendations to reduce emissions at the local level.

Since 2020, all enterprises with a significant impact on air pollution, such as producers of coke, pig iron, steel, cement, and others, have been required to install measuring equipment and monitor their emissions. As of 2023, this list has been expanded to include manufacturers of glass and fiberglass.

The government has divided responsibilities among experts to ensure the credibility of greenhouse gas emissions reports. First, specialists at the enterprise prepare the report based on monitoring results. Then, an independent verifier—an organization officially accredited by the government—checks whether air quality monitoring was carried out correctly, with full access to all facilities and measuring equipment. After that, another individual—a peer reviewer selected by the verifier but not affiliated with them (for example, a representative of a scientific institution)—reviews the report. This person does not have access to the measuring equipment and is not permitted to take part in preparing the report. The peer reviewer signs off on the report, assuming responsibility for its final validation. This system prevents any one person from preparing, verifying, and approving the same report.

Water

Directive 2000/60/EC on water policy sets out rules for managing river basins and obliges member states to achieve “good ecological status” for all water bodies.

For Ukraine, this means developing a national river basin management strategy, enforcing stricter wastewater treatment requirements, reducing pollution in the Dnipro and other rivers, and limiting the use of nitrates and pesticides in agriculture.

What has been done so far? In 2017, Ukraine adopted rules for developing river basin management plans—a key document for systematically protecting water resources. Ukraine is committed to implementing integrated water management, including surface and groundwater, as part of its adaptation to the EU Water Framework Directive. To support this, in 2019, the Ministry of Environment approved a methodology for identifying water bodies—sections of river basins that should be assessed separately. This has allowed for more targeted monitoring and better response to risks.

River basin management plans have now been developed for Ukraine’s major basins—the Dnipro, Dniester, Danube, Southern Bug, and Don, as well as rivers in Crimea and the Azov region. In 2023, the Ministry of Environment conducted water sampling and observations at 492 out of 585 planned monitoring points (84%). As a result, it was found that 24% of water bodies are in good condition (not at risk), 15% are likely to be at risk, and 61% are at risk. This includes risks of pollution, depletion of water resources, and disruption of natural processes. Monitoring covers around 80 indicators at each observation point, and the results are available online in real time.

The war has significantly worsened the situation. In addition to widespread pollution, Ukraine’s water system has suffered physical destruction. The most devastating events were the blowing up of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, which destroyed and damaged a vast reservoir, and the damage to the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station. These events have disrupted the hydrological regime, worsened reservoir conditions, and affected water supply across regions.

The quality of the country’s air and water systems largely depends on controlling emissions from major industrial enterprises and effective waste management.

Environmentally responsible enterprises

In industrial pollution control, the key document is Directive 2010/75/EU on industrial emissions (specifically, on the prevention and control of environmental pollution). It introduces integrated environmental permits—a single license covering all significant ecological impacts of an enterprise, including air emissions, water discharges, and solid waste generation—for facilities with significant environmental effects, such as those in the energy, chemical, and metallurgical sectors. The directive also requires businesses to apply Best Available Techniques (BAT) to reduce air, water, and soil emissions.

For Ukraine, implementing this directive means introducing environmental permits for enterprises whose operations result in harmful air, water, or soil emissions. This will enable the government to strengthen control over emissions from metallurgical plants, thermal power stations, and chemical industries, reducing industrial pollution and health risks for the population.

What has been done so far? Since 2023, enterprises have been required to install automated emission monitoring systems. A bit later, in 2024, Parliament passed the Law on Integrated Prevention and Control of Industrial Pollution. This law adopts the European approach to emissions control, requiring enterprises to apply Best Available Techniques (BAT), and stipulates that the Ministry of Environment will issue integrated environmental permits for operating equipment. The law mandates that enterprises must implement BATs, minimize ecological harm, and report on their emissions. For existing enterprises, the transition to BATs will begin four years after the end of martial law.

Recycling instead of landfilling

If an enterprise generates waste, it must participate in organizing its recycling. Extended producer responsibility means businesses are expected to minimize waste generation during production and arrange for the reuse, recycling, or proper disposal of the waste they create.

The key legal framework for waste management is Directive 2008/98/EC, which sets out general EU requirements for waste handling. It establishes the waste management hierarchy (prevention, preparation for reuse, recycling, other recovery, and disposal), along with the “polluter pays” principle and extended producer responsibility. Other necessary directives include Directive 94/62/EC on packaging, Directive 2006/66/EC on batteries, and Directive 2012/19/EU on electronic waste.

For Ukraine, implementing these directives means that domestic producers will be required not only to design products with end-of-life disposal in mind but also to take part in the systems for collecting, transporting, and recycling waste. This will reduce the burden on landfills, lessen environmental harm, and create economic incentives for more eco-friendly product design. For consumers, it will mean greater access to recycling collection points and a clearer system for handling hazardous household waste.

What has been done so far? In Ukraine, extended producer responsibility is established by the Law on Waste Management. The law requires producers, such as manufacturers of packaging, electronics, batteries, or tires, to organize the collection and recycling of their waste, either individually or collectively through special entities known as Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs), i.e., non-profits established by producers to collect waste and prepare it for reuse. These organizations must operate across Ukraine, inform the public about collection and recycling practices, conduct awareness campaigns (including in educational institutions), track waste collection and recycling, report to the Ministry of Environment through an electronic system, and cover recycling costs. If producers or PROs fail to comply with these requirements, they face fines to be determined by separate laws. Specific rules and requirements for the recycling of each product category will also be defined by separate legislation. A draft law on Packaging and Packaging Waste has already been prepared (but not yet adopted) as part of this reform. If passed, it will implement Directive 94/62/EC, which requires that packaging be minimized in size, weight, and hazardous content and be suitable for reuse or recycling. The draft law would also introduce producer responsibility for the disposal of packaging. Fines for producers and PROs who fail to comply with the law range from UAH 85,000 to UAH 340,000.

A similar draft law, On Batteries and Accumulators, has been developed based on Directive 2006/66/EC on waste batteries and accumulators. It aims to introduce a system for collecting, disposing, and recycling batteries, as they pose a serious environmental threat. Batteries can contaminate soil and groundwater with hazardous substances when disposed of in regular landfills. Batteries contain heavy metals—lead, cadmium, mercury—that accumulate in the soil, enter water sources, and can cause neurological disorders, kidney disease, cancer, and other serious health problems in humans. Following the Directive 2012/19/EU model, a draft law on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment is also being prepared. Its goal is to establish clear rules for businesses on handling electronic waste and to assign producers responsibility for the entire life cycle of electronic devices—from production to disposal.

We previously wrote about the waste management reform

If waste cannot be recycled, it must be stored in landfills. In this area, the key document is Directive 1999/31/EC, which regulates landfill operations. It sets requirements for sealing and leachate and gas collection and prohibits the landfilling of untreated organic waste, which produces methane.

For Ukraine, implementing the directive means closing outdated landfills, introducing separate waste collection, developing organic waste processing (such as composting and biogas plants), and gradually phasing out illegal dumpsites, which remain one of the country’s major environmental problems. Every year, Ukraine generates around 500,000–550,000 tons of hazardous waste. Almost all of it (95%) ends up in landfills, while only a small portion is recycled. In comparison, EU countries recycle between 40% and 99% of their waste. According to the Ministry of Environment, there are 5,700 official landfills and dump sites in Ukraine. However, environmental activists estimate the number of illegal dump sites to be between 33,000 and 35,000.

What has been done so far? In 2017, the Ukrainian government approved the National Waste Management Strategy until 2030 to implement a systematic approach to waste management. In 2019, a follow-up Action Plan was adopted, requiring local authorities to begin constructing regional waste landfills and close or remediate existing hazardous dumpsites. These measures bring Ukraine closer to meeting the requirements of Directive 1999/31/EC, which not only sets targets for reducing municipal waste—such as plastic bottles, food scraps, cardboard, and glass—going to landfills (by 2035, such waste should make up no more than 10% of total landfill waste, with the rest being sorted, recycled, composted, or incinerated) but also outlines technical standards for landfill construction. Specifically, landfill bases and walls must be lined with special mineral layers of very low permeability to prevent soil and groundwater contamination. The minimum thickness of this protective layer varies depending on the type of landfill, from 0.5 to 5 meters.

In 2022, to implement the above-mentioned Directive 1999/31/EC and Directive 2008/98/EC on waste, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted a framework law On Waste Management. This law introduces the following waste management hierarchy: prevention, reuse, recycling, recovery, and disposal. To put the law into practice, the government developed regulations for creating regional and local waste management plans and approved procedures for monitoring how enterprises process or dispose of waste. These facilities may include plants or other sites where waste is either reused (e.g., as fuel) or neutralized (through incineration, burial, or discharge into water). Waste treatment facilities may include sorting stations, incineration plants, or landfills. In addition, businesses must now submit declarations for waste volumes exceeding 50 tons per year. All waste-related data is collected through the Ministry of Environment’s information system—the Unified Environmental Platform “EcoSystem.”

The government has approved a waste classification system that defines 20 categories of waste, such as mining waste, chemical processing waste, wood and metal waste, and animal and plant waste, based on their origin, whether they are hazardous, and whether they contain high concentrations of harmful substances. A national waste list has also been established.

In production, enterprises generate not only waste but also by-products. These are not considered waste but are materials formed during production that can be reused without harming the environment. For example, sawdust from a woodworking plant can produce pellets or particleboard. To this end, the government approved procedures for classifying substances as by-products and ending waste status, when a processed waste material becomes a full-fledged raw material or product rather than waste. For instance, crushed construction debris can be used as road gravel and is no longer considered waste. The government also adopted procedures for licensing activities related to hazardous waste management, issuing permits for waste processing, tenders for municipal waste transportation services, etc.

In November 2024, the government submitted a draft law on how to manage waste generated from the extraction of mineral resources, such as contaminated water, sludge, dust, rocks, or toxic substances that accumulate near mines, quarries, or processing plants, as well as residues from ore processing. Previously, such waste was often stored in dumps near production sites, mines, or quarries without proper oversight, which caused environmental harm. The new draft law aims to introduce European standards requiring enterprises to store this waste safely, monitor its environmental impact, and take measures to prevent accidents.

No to industrial accidents

In preventing industrial hazards, the cornerstone is Council Directive 96/82/EC. It outlines the requirements for identifying high-risk industrial sites, conducting risk assessments, developing accident prevention policies and response plans, and mandates that states inform the public about potential threats. In 2012, this Directive was replaced by Directive 2012/18/EU, which further strengthened provisions on public awareness, land-use planning near hazardous facilities, and inspection mechanisms. Under the updated directive, all facilities exceeding specified thresholds for hazardous substance emissions must be included in a single registry, undergo risk evaluations, prepare safety reports, and ensure effective communication with the public and government authorities. The directive also guarantees public access to environmental information and the right to influence decisions regarding the placement of such sites.

For Ukraine, implementing these directives is essential due to the high level of technological risk, the significant number of industrial enterprises, and the increased likelihood of structural damage and hazardous emissions as a result of missile attacks by Russia. Ukraine must transition to a systematic approach to managing the risks of industrial accidents. This requires adopting legislation mandating risk assessments for high-risk facilities, establishing a Unified State Register of such sites, and introducing uniform accident prevention and response standards. Enterprises handling hazardous substances would be required to develop internal action plans, while government authorities would be responsible for external response plans coordinated with local communities. At the same time, transparency must be ensured: citizens living near such sites should have full access to information about potential risks, preventive measures, and emergency procedures.

What has been done so far? At the foundational legal level, the Civil Protection Code of Ukraine plays a key role. It establishes the legal framework for implementing state policy on protecting the population and territories from emergencies, including technological ones. The Code defines mechanisms for responding to accidents, procedures for mitigating their consequences, central and local executive authorities’ powers, and requirements for civil protection planning in case of emergencies. In addition to the Code, in 2023, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine established the State Electronic Register of High-Risk Facilities. This register is intended to collect information on all facilities where accidents could result in significant man-made consequences. At present, the register is not publicly accessible.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Internal Affairs has obligated enterprises to report on safety measures at high-risk facilities, incorporating structured risk assessments. It has introduced policies aimed at preventing accidents at such sites. In 2023, Ukraine ratified ILO Convention No. 170 on the safety of chemical substances and established the State Register of High-Risk Facilities.

The Ukrainian government also continues to fulfill commitments outlined in the 1995 Memorandum on the complete shutdown of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant—encompassing decommissioning and the safe storage of radioactive materials, as well as the transformation of the “Shelter” (the sarcophagus over the destroyed Unit 4) into an environmentally safe structure. In February 2025, Russian forces damaged the protective arch covering the old sarcophagus, which had been designed to prevent radiation leaks.

Environmental governance

Directive 2001/42/EC plays a pivotal role in environmental governance and the integration of environmental policy. It requires environmental impact assessments to be conducted while developing plans and programs across various economic sectors to prevent ecological harm at the planning and strategic document preparation stages (such as regional or sectoral development plans and programs).

For Ukraine, implementing this directive means that authorities must assess the potential environmental impact of strategic documents during their development to prevent ecological disasters in the future.

What has been done so far? Significant progress in environmental governance and policy integration has been made with the adoption of the Law on Environmental Impact Assessment (2017) and the Law on Strategic Environmental Assessment (2018), both of which implement the provisions of Directive 2001/42/EC related to environmental risk assessments in planning and programming. In 2023, Parliament passed a law establishing a national environmental monitoring system. This system includes a central reference laboratory—a state institution responsible for ensuring the accuracy and quality of air monitoring data, calibrating equipment, auditing other laboratories, developing standards, and enforcing uniform air quality assessment protocols nationwide.

Ukraine is steadily moving toward a modern European environmental policy framework. A key step was the introduction of a law on the digitalization of the environmental impact assessment procedure. This ensures that all construction or infrastructure reconstruction decisions now consider ecological consequences. A unified electronic register for Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEAs) has been created as part of this modernization. All documents related to the environmental assessment of plans and programs are now stored in a single open-access online register, available to citizens and civil society organizations. This transparency enables anyone to see who is building what, how it may impact the environment, and to submit comments or objections.

Another significant development was the creation of the national automated system, “Open Environment.” This platform will gradually integrate all environmental data across the country, from air and water quality to pollution sources, into a single government portal. Environmental agencies, local authorities, and enterprises will supply the data. This system will allow citizens to track the ecological status of their cities and towns while giving environmental professionals tools to respond quickly to violations.

In addition, in 2017, Ukraine adopted the National Waste Management Strategy until 2030. The strategy aims to shift the entire country to a separate waste collection system, establish recycling infrastructure, and ensure that most waste is reused or converted into energy rather than sent to landfills. The goal is to reduce landfill disposal to a minimum (currently, over 90% of waste is landfilled) and achieve a household waste recycling rate of at least 50% by 2030.

That same year, Ukraine also adopted the National Emissions Reduction Plan for Large Combustion Plants, which applies to more than 200 power stations and boiler facilities. By 2033, these installations must reduce dust emissions, nitrogen oxides (NOx), and sulfur dioxide (SO₂)—the main contributors to air pollution. The National Plan sets specific targets and deadlines for each facility. For example, total SO₂ emissions must be reduced twentyfold—from 1 million tons in 2018 to 51,000 tons by 2028–2033. Energy companies are responsible for implementing the necessary upgrades, while enforcement falls under the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine. According to DTEK, as of mid-2024, 90% of Ukraine’s thermal power generation and 45% of hydro generation had been damaged or destroyed. Data from the Kyiv School of Economics estimates losses and damages in the energy sector at $14.6 billion. Russia has destroyed the Kakhovka and Dnipro Hydroelectric Power Stations and the Trypillia and Zmiiv Thermal Power Plants. It has damaged or obliterated many other generating facilities and high-voltage substations.

Nature protection

A cornerstone of nature protection policy is Council Directive 92/43/EEC, commonly known as the Habitats Directive. Its primary goal is to preserve biodiversity by establishing a network of Special Areas of Conservation known as Natura 2000. The directive defines criteria for selecting these sites, outlines their protection and management mechanisms, and sets requirements for monitoring the conservation status of species and habitats.

To comply with the Habitats Directive, Ukraine must legally designate natural habitats and species of flora and fauna requiring protection, establish a national monitoring system to track their conservation status, implement an environmental impact assessment procedure for planned economic activities affecting these areas, and identify and officially approve a list of territories that will be integrated into the European Natura 2000 network. This would open the door to EU funding for conservation efforts and support sustainable development that accounts for environmental risks.

What has been done so far? Ukraine has been actively improving its biodiversity protection framework. In 2021, the government approved the Forest Management Development Strategy until 2035, which focuses on modernizing and digitizing forest governance, increasing forest resilience to climate change, promoting recreational use of forests, supporting scientific research, and training professionals. A comprehensive forest inventory is underway, and the government is implementing the President’s “Green Country” initiative, which aims to plant 1 billion trees over five years and expand forested areas by 1 million hectares over the next 15 years.

Since 2009, Ukraine has also been working on the Emerald Network—a protected area system crucial for preserving rare species and habitats. Under the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, this work was to be completed by September 1, 2021, but the process is still ongoing.

Once Ukraine joins the European Union, it will be expected to integrate its protected areas into the broader Natura 2000 network. Ukraine has 377 Emerald Network sites that have received international recognition, but Parliament has not yet formally approved them in law. A draft law on Emerald Network territories, developed between 2020 and 2021, aims to resolve this. It proposes that the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources and local state administrations manage these areas. Adopting this law would also enable Ukraine to access EU funding for environmental protection, but the bill has yet to be passed.

In 2024, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the draft law On Forest Reproductive Resources at first reading. This legislation establishes rules for producing, certifying, circulating, and using seeds and planting material for forest regeneration. It provides for the creation of registries for seed sources, producers, and certificates and mandates quality control. The law aligns Ukraine’s regulatory framework with Directive 1999/105/EC, which governs the trade of forest reproductive material in the EU, including requirements for certification, labeling, and traceability.

Climate change and ozone layer protection

The cornerstone of the European Union’s climate change policy is Directive 2003/87/EC, which established the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). This system covers large industrial and energy enterprises, requiring them to obtain emission allowances and incentivizing emissions reductions through market-based mechanisms. In the area of ozone layer protection, the key regulations are Regulation (EC) No 1005/2009 (which replaced Regulation No 2037/2000, included in the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement), governing the trade in ozone-depleting substances, and Regulation (EU) No 517/2014, which replaced Regulation No 842/2006 and regulates fluorinated greenhouse gases. These instruments aim to restrict and gradually phase out the use of substances harmful to the atmosphere.

Implementing these directives in Ukraine entails adopting national legislation to create a domestic greenhouse gas emissions trading system. The government must also establish a robust framework for monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) of emissions, covering extensive industrial and energy facilities. In the area of ozone protection, Ukraine needs legal mechanisms to control the circulation of ozone-depleting substances and fluorinated gases. These steps would enable effective state oversight of emissions, encourage businesses to reduce them, and help integrate Ukraine into international carbon markets.

What has been done so far? To protect the ozone layer, in 2019, the Ukrainian Parliament adopted the Law on the Regulation of Economic Activities Involving Ozone-Depleting Substances and Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases. This law aligns with relevant EU regulations and restricts the use of substances harmful to the ozone layer.

In 2021, the Verkhovna Rada passed the Law on the Fundamentals of Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, establishing the national MRV system and laying the foundation for a domestic emissions trading scheme. In 2023, the Cabinet of Ministers updated the emissions monitoring and verification regulatory framework. That same year, the government began work on preparing Ukraine’s Second Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) under the Paris Agreement (ratified by Parliament in 2016), setting a target to reduce CO₂ emissions by 65% compared to 1990 levels, bringing them down to 50 million tons by 2030. However, the full-scale invasion by Russia has severely disrupted Ukraine’s ability to meet its climate commitments. Over three years of full-scale war, Ukraine’s greenhouse gas emissions have reached an estimated 230 million tons of CO₂, mainly due to fires sparked by combat operations and the destruction of energy infrastructure through missile strikes. This level of emissions is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia, or 120 million cars in one year. The total climate-related damage caused by Russian aggression over this period is estimated to exceed €40 billion.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs)

In the field of GMO regulation, the key legal instrument is Directive 2001/18/EC, which establishes rules for the deliberate release of GMOs into the environment and their placement on the market. The directive requires risk assessments for human health and the environment, mandatory labeling of products containing GMOs, and public access to information regarding potential GMO-related risks. Directive 2009/41/EC regulates the contained use of genetically modified microorganisms (GMMs) in closed systems, such as laboratories, to ensure the safety of workers and the environment. In addition, Regulation (EC) No 1946/2003 sets out procedures for the transboundary movement of GMOs, including requirements for notification and the prior informed consent of importing countries.

Transposing these directives into Ukrainian law means the country must introduce mandatory health and environmental risk assessments before using GMOs in agriculture or marketing GMO-containing products. It also requires establishing labeling rules for GMO-containing products, public access to information about such goods, a control system for using GMOs in closed environments (e.g., laboratories), and a mechanism for overseeing the transboundary movement of GMOs. These measures must be enshrined in dedicated legislation and bylaws aligned with EU directives.

What has been done so far? In 2023, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the Law on State Regulation of Genetic Engineering Activities and State Control over the Placement of Genetically Modified Organisms on the Market, aimed at implementing Directive 2001/18/EC. This law sets out procedures for registering GMOs, labeling requirements, and the obligation of producers to inform consumers. Under the Law on the Basic Principles and Requirements for Food Safety and Quality, producers must label products with the phrase “contains GMOs” if genetically modified organisms or their derivatives are present in concentrations exceeding 0.9%.

In summary

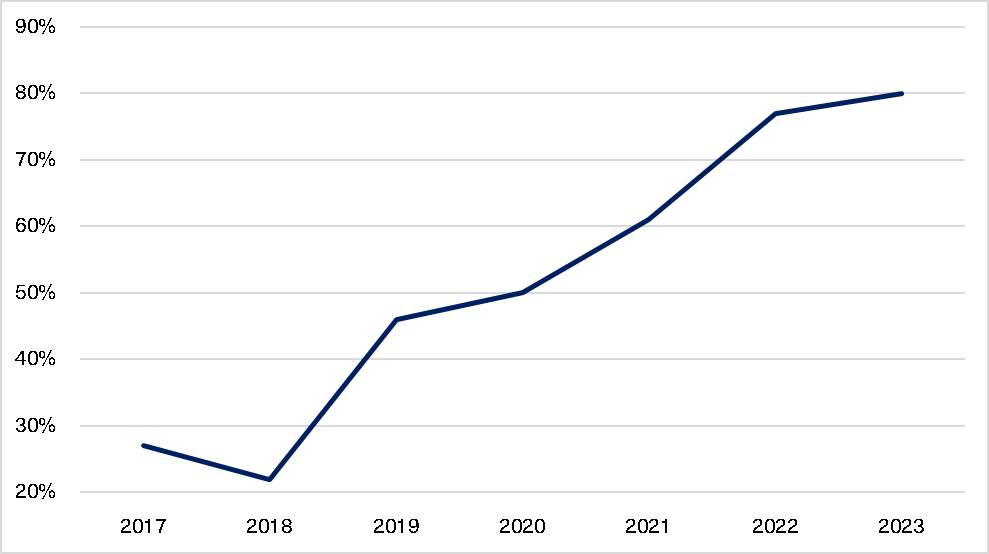

As of 2023, Ukraine had implemented 80% of the measures outlined in the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement regarding environment and civil protection.

Figure 2. Progress in the implementation of measures under the “Environment and Civil Protection” chapter of the Association Agreement

Source: Reports on the implementation of the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU

The full-scale invasion by Russia has significantly impacted Ukraine’s fulfillment of its environmental commitments. The primary challenges include large-scale ecological damage, such as the destruction of industrial facilities, the demolition of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, forest fires, and soil contamination. The total ecological damage is estimated at UAH 2.6–2.7 trillion. Environmental policy has shifted to the background due to urgent military needs, and monitoring pollution in the frontline and occupied territories has become significantly more difficult.

The implementation of environmental policy remains unsatisfactory due to several systemic issues, most notably the weak institutional capacity of government bodies in the environmental sector. Environmental control functions are fragmented across various agencies, leading to overlapping mandates and inefficiencies. For example, the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources shapes environmental policy. However, oversight functions are divided among the State Environmental Inspectorate, the State Water Agency, the State Forest Agency, the Ukrainian Geological Survey (State Service of Geology and Mineral Resources), and regional state administrations. In contrast, EU countries operate independent environmental agencies following EU regulations. Examples include the European Environment Agency, the Federal Environment Agency (UBA) in Germany, the French Agency for Ecological Transition (ADEME), and the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL). These independent environmental agencies are state institutions that objectively oversee environmental conditions and operate autonomously from ministries. Unlike Ukraine’s sectoral agencies (such as the State Environmental Inspectorate, State Water Agency, State Forest Agency, and State Geology Service), which are responsible only for individual areas (e.g., water, forests, minerals), an independent environmental agency in the EU is a single, autonomous, and depoliticized body that conducts comprehensive environmental monitoring, control, and analysis across all environmental domains.

Another significant issue is the underdeveloped environmental monitoring system. For instance, Ukraine’s air quality monitoring network consists of 162 stationary stations (compared to 129 in 2022, while Poland had 287 air quality monitoring stations in 2021), two mobile observation units, and two transboundary transport stations, all of which fall under the jurisdiction of the State Hydrometeorological Service. These monitoring stations (or laboratories) operate in 53 cities across Ukraine. However, most stations are outdated and fail to meet modern standards. For example, many are not automated or connected to digital data collection and transmission systems, and were originally installed as far back as the 1980s. As a result, they cannot provide up-to-date information on air quality in real time. According to the NGO SaveDnipro, a significant portion of environmental data in Ukraine remains inaccessible, which severely limits the ability to respond quickly to pollution incidents, especially in industrial regions.

Passing laws is only the first step. Implementation requires funding, administrative capacity, and changes in public behavior.

Despite the Procedure for State Water Monitoring, according to the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, only 30% of wastewater in Ukraine underwent basic treatment in 2021. By contrast, EU countries treated over 90% of their wastewater as of 2019. Moreover, the government does not exercise adequate control over nitrate and phosphate discharges from agriculture. In other words, while monitoring is in place, it has not translated into actual reductions in water pollution.

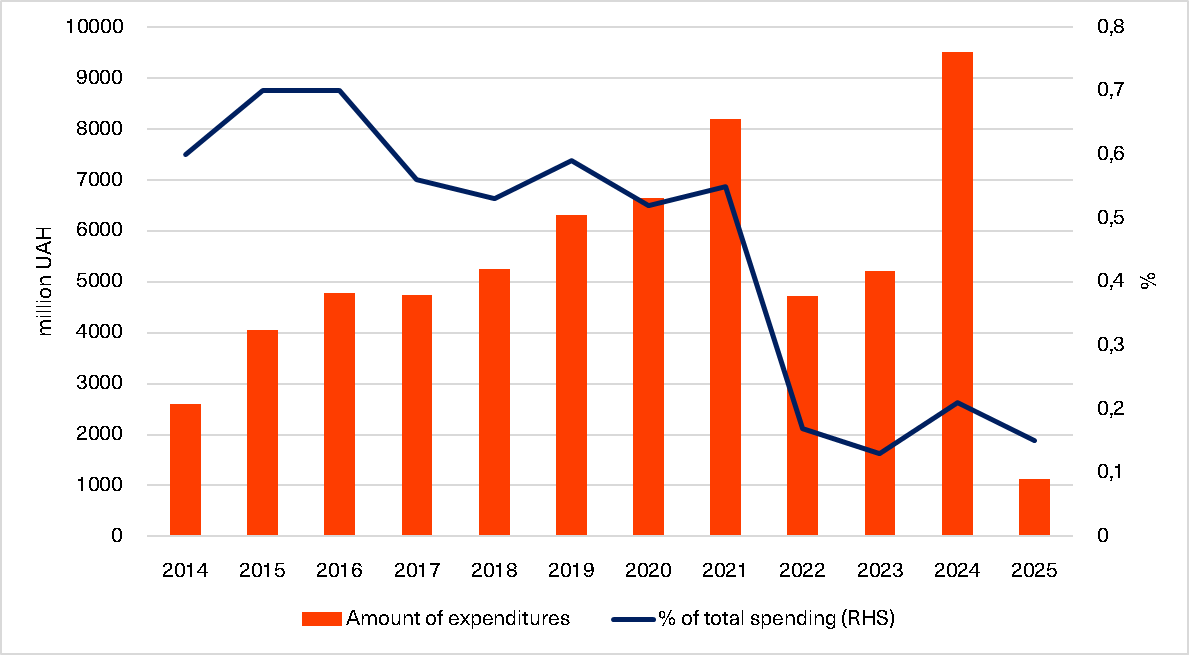

The radioactive waste management program for 2008–2017 was funded at only 10% of its planned level, highlighting a chronic lack of resources. During wartime, environmental expenditures have declined even further. For example, planned environmental protection spending for 2025 accounts for just 0.15% of total state budget expenditures (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. State budget expenditures on environmental protection

Source: State budget expenditures of Ukraine (functional classification) for 2014–2025 at year-end (for 2025 — as of March), in UAH million and as a percentage of total budget expenditures.

Thus, while Ukraine has taken necessary steps toward environmental integration with the EU, implementing EU directives involves more than just changes to legislation. To address the challenges outlined above, Ukraine must strengthen the institutional capacity of its environmental authorities, establish an effective environmental monitoring system, integrate ecological policy into other economic sectors, expand mechanisms for corporate environmental responsibility, embed environmental requirements into the country’s post-war recovery processes, develop waste processing infrastructure, ensure adequate funding for environmental initiatives, and implement modern mechanisms for controlling industrial pollution. Only comprehensive reforms will enable Ukraine to fulfill its commitments to the EU and ensure sustainable development in environmental protection.

Appendix

Ukraine’s Commitments

| Direction | EU Norms | Measures to Be Implemented by Ukraine |

| Environmental Governance and Policy Integration | Directive 2011/92/EU, Directive 2001/42/EC, Directive 2003/4/EC, Directive 2003/35/EC | Adopting national legislation and designating a competent authority (or authorities); establishing requirements for environmental impact assessments of projects; public and governmental consultations; ensuring public access to environmental information; introducing mechanisms for strategic environmental assessments of plans and programs; reaching agreements with neighboring countries on information exchange and consultations. |

| Air Quality | Directive 2008/50/EC, Directive 2004/107/EC, Directive 98/70/EC, Directive 1999/32/EC, Directive 94/63/EC, Directive 2004/42/EC | Adopting national legislation and designating a competent authority; establishing air quality standards and pollutant concentration limits; defining and classifying zones and agglomerations; creating an air quality monitoring system; implementing air quality improvement plans in problem regions; developing short-term action plans in cases of excessive pollution; banning the use of high-sulfur heavy diesel fuels. |

| Waste and Resource Management | Directive 2008/98/EC, Directive 1999/31/EC, Directive 2006/21/EC | Adopting national legislation and designating a competent authority; developing waste management strategies and plans; introducing the “polluter pays” principle and extended producer responsibility; establishing a permitting system for waste management enterprises; creating registries for entities collecting and transporting waste; classifying landfill sites; developing biodegradable waste reduction programs; remediating existing landfill sites. |

| Water Quality and Water Resource Management | Directive 2000/60/EC, Directive 2007/60/EC, Directive 2008/56/EC, Directive 91/271/EEC, Directive 98/83/EC, Directive 91/676/EEC | Adopting national legislation; identifying river basins and establishing river basin management authorities; introducing water quality monitoring; preparing water resource management plans; conducting risk assessment and hazard mapping for floods; developing a marine strategy in cooperation with EU countries; identifying sensitive zones for urban wastewater treatment; establishing a drinking water quality monitoring system. |

| Nature Protection | Directive 2009/147/EC, Directive 92/43/EEC | Adopting national legislation, creating registries of protected areas, introducing mechanisms to protect habitats of rare species, implementing measures to protect migratory bird species, and establishing a system to monitor the conservation status of habitats and species. |

| Industrial Pollution and Technogenic Hazards | Directive 2010/75/EU, Directive 96/82/EC | Establishing an integrated permitting system; introducing Best Available Techniques (BAT); creating a system to monitor industrial emissions; identifying risks of man-made accidents and developing response systems; creating an accident registry and reporting system for major incidents. |

| Climate Change and Ozone Layer Protection | Directive 2003/87/EC, Regulation (EC) No 842/2006,

Regulation (EC) No 2037/2000 |

Introducing a greenhouse gas emissions trading system, developing national emissions reduction plans, creating reporting mechanisms for fluorinated gases, and gradually phasing out ozone-depleting substances. |

| Genetically Modified Organisms (GMOs) | Directive 2001/18/EC, Regulation (EC) No 1946/2003,

Directive 2009/41/EC |

Establishing GMO risk assessment procedures; creating registries of GMO cultivation sites; ensuring proper labeling of GMO-containing products; introducing mechanisms for informing the public about GMO-related risks. |

Source: Annex XXX to the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations