In recent years, emerging market (EM) countries have significantly increased the use of their local currencies in international transactions. However, the shares of these currencies remain small on a global scale, while the U.S. dollar retains its absolute dominance among currencies used for trade and investment transactions. What explains this trend—and what comes next?

What the data show

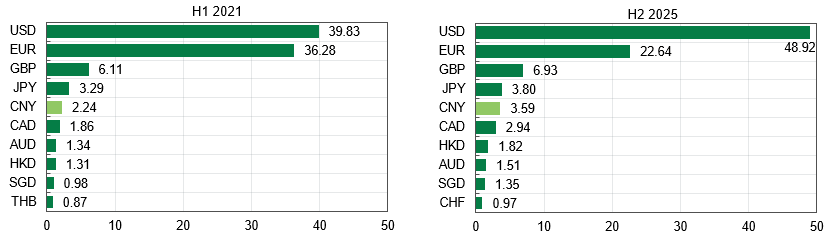

Among the currencies of EM countries, the Chinese yuan is the most actively used—about 3.6% of all international payments (all transactions implemented via the SWIFT system, that is, SWIFT MT 103, MT 202 cross-border payments, and ISO equivalent) in the first half of 2025, compared with 2.2% four years ago. However, the relative share of the yuan—like that of other EM currencies—remains small despite the upward trend, especially compared with leading currencies. For instance, the share of the U.S. dollar was about 50%, and the share of the euro stood at 22.6%.

Chart 1. Top 10 currencies by use in global payments, % of total transaction value (period average)

Source: SWIFT, Bloomberg, authors’ calculations

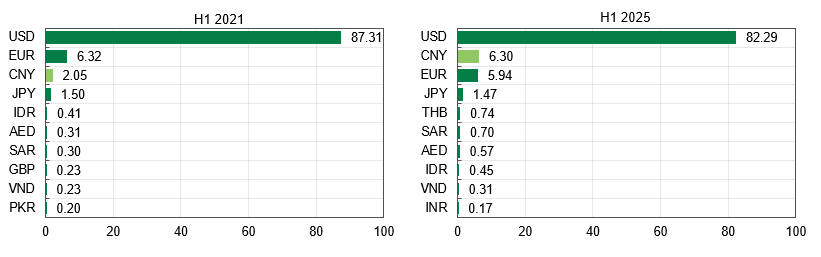

Meanwhile, in trade finance (for example, loans for foreign trade, including documentary transactions with payment through letters of credit), the share of the yuan has grown significantly in recent years—to 6.3% in the first half of 2025 (from about 2% four years ago), approaching the share of the euro and far exceeding that of the yen. The top ten most widely used currencies in trade finance also include the Thai baht, Saudi riyal, UAE dirham, Indonesian rupiah, Vietnamese dong, and Indian rupee. However, their relative shares are each below 1%. The undisputed leader in servicing trade finance transactions remains the U.S. dollar (82.3 percent).

Chart 2. Top 10 global currencies in the trade finance market, % of total transaction value (period average)

Source: SWIFT, authors’ calculations

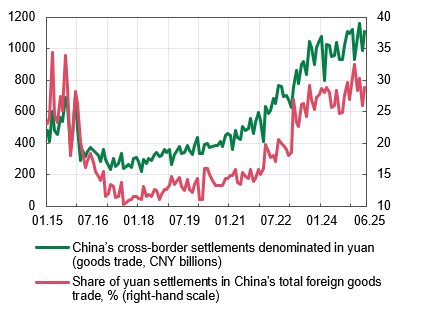

Over the past ten years, China has increased its settlements and payments for international trade transactions in its national currency. In absolute terms, international settlements for goods trade amounted to CNY 1.11 trillion (about USD 154.5 billion) in June 2025, compared with CNY 483.4 billion (≈ USD 77.7 billion) at the beginning of 2015 (according to Bloomberg).

Chart 3. China’s settlements for foreign trade in goods in yuan

Source: Bloomberg, PBOC

At the same time, the share of yuan settlements in China’s total foreign trade stood at 28.8% in June 2025. The indicator shows an upward trend but is still lower than in 2015, when the peak share reached 34.4%—a result that can be explained by the yuan’s depreciation due to capital outflows and the central bank of China’s policy of stimulating exports.

China’s attempts to reduce dependence on the U.S. dollar

These efforts were preceded by the escalation of trade tensions between the United States and China after 2016, including restrictions on the export of key technologies.

In 2025, against a backdrop of heightened tensions, China is once again intensifying its push to internationalize the yuan. In particular, in May 2025, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) called on major banks to increase the share of yuan in international trade transactions to 40% from the current 25%. In addition, China is expanding the international use of its UnionPay payment system, whose network of agreements covers more than 30 countries. Using UnionPay payments via QR codes in Southeast Asian countries is boosting transactions by tourists and small businesses, reducing reliance on the dollar.

The yuan’s strengthening has also been supported by China’s policy of developing its financial sector and expanding the international role of its national currency. In particular, the Chinese government has taken a number of steps to promote the yuan in bilateral trade relations. In September 2021, the Local Currency Settlement (LCS) cooperation mechanism between China and Indonesia was launched. In March 2023, China and Brazil reached an agreement to conduct trade between the two countries in their national currencies. Since 2022, China has expanded international lending in yuan: in 2021, only about 17% of China’s cross-border loans were denominated in yuan, while by early 2024 this share had reached 32%. New clearing banks have been actively opened, including in Laos, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, and Brazil, and both the volume and the number of commodity market trade agreements denominated in yuan have been increasing.

China is increasingly expanding its network of swap lines—currently, agreements have been concluded with more than 40 other central banks (in addition to bilateral swap lines, the PBoC also participates in multilateral initiatives that use currency swap mechanisms, such as the Chiang Mai Initiative and the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement). For example, in just the past few years, currency swap agreements have been activated with the central banks of Argentina, Egypt, Laos, Mongolia, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. As of February 2025, the available volumes of bilateral currency swap lines between the PBoC and other central banks had reached CNY 4.3 trillion (≈ USD 591 billion). Note that the size of signed swap lines differs from the actually used (i.e. activated) volumes of funding. Furthermore, in June 2025, the central banks of China and Turkey signed a memorandum of understanding to establish yuan clearing arrangements in Turkey.

The PBoC’s network of swap lines has become an important tool of international crisis management alongside lending under aid programs (so-called rescue lending), and China itself has become a key “lender of last resort” for EM countries. China’s introduction of bilateral swap lines and offshore clearing banks is aimed at facilitating settlements for international trade transactions in yuan and expanding the yuan’s presence on the global stage—especially given that its liquidity outside China is limited due to the country’s controls on cross-border capital flows.

Initially, the geography of swap lines was concentrated in the Asian region; later, other EM countries were added. Countries that make use of financing under the PBoC’s swap lines are typically those with low reserves and weak credit ratings, doing so during periods of financial or macroeconomic distress. Recently, several central banks from advanced economies—including Canada, the ECB, and the United Kingdom—have concluded agreements to open swap lines with the PBoC as a mechanism for managing financial stability risks. However, China’s swap agreements and loans to leading economies do not play a significant role in expanding the use of the yuan in international transactions.

The use of national currencies by sanctioned countries

Sanctioned countries, including Russia, have also turned to using the yuan for settlements and payments. Even before its military aggression against Ukraine, Russia had been developing bilateral ties with China to facilitate transactions in local currencies. It began in 2010 with the launch of direct trading between the ruble and the yuan on the interbank foreign exchange market, followed in 2011 by the expansion of an agreement to conduct trade settlements in national currencies between the two countries (previously limited to border regions).

After sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2022, including freezing its central bank’s assets and excluding many Russian banks from the SWIFT system, the country faced acute difficulties in carrying out international transactions in dollars or other major currencies. As a result, most trade and investment activity between Russia and China began to be conducted in yuan or rubles. China significantly increased the use of the yuan in settlements for imports of Russian goods, particularly oil, coal, and certain metals (the yuan share in 2022 rose from 4% to 23%). Russia also agreed to accept Chinese yuan and UAE dirhams from India for oil payments. Trade agreements in rubles also grew substantially—from 18% of Russia’s total foreign trade in January 2022 to 34% by the end of 2023.

After the first sanctions were imposed on Russia in 2014 and discussions began about restricting its access to SWIFT, the Russian central bank started looking for ways to reduce reliance on that system. The Russian central bank created the SPFM (System for Transfer of Financial Messages) platform. At present, more than 580 users—including banks, nonbank financial institutions, and companies—from Russia and 24 other countries are connected to SPFM. However, the potential for further international expansion of this alternative system is very limited due to new sanctions and warnings from the United States about the risk of sanctions for jurisdictions that join the Russian system.

After 2022, many Russian banks converted their foreign currency assets into yuan-denominated assets and switched from the U.S. Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) to China’s CIPS (RMB Cross-Border Interbank Payment System, launched in 2015), which specializes in yuan transactions. The currency swap mechanism between the Russian and Chinese central banks is also actively used; according to official PBoC data, their first bilateral agreement was signed back in October 2014 for CNY 150 billion (≈ USD 24.5 billion) and was renewed in 2017 and 2020. In 2016, the two central banks signed a memorandum of understanding to establish yuan clearing mechanisms in Russia.

In addition, sanctioned countries are seeking to develop the use of local digital currencies to circumvent sanctions. In particular, countries under financial sanctions (Russia, Iran, and North Korea) view the use of the digital yuan (e-CNY) as a viable alternative to the Western SWIFT-based payment transfer system and support the adoption of China’s digital currency (a pilot project for introducing it in selected regions of China has been underway since April 2020).

Another example of a sanctioned country using national currencies—other than the yuan—for international settlements and payments is Iran. There is potential for increased use of the Indian rupee in trade settlements between Iran and India, especially in the context of a significant expansion in bilateral trade volumes (in 2022, India’s imports from Iran grew by 60% compared with 2021, while exports rose by 44%). At meetings in 2022 and 2023, Iran and India discussed the feasibility of expanding trade in rupees and establishing the necessary banking mechanisms.

BRICS Initiatives

For more than a decade, BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have been discussing the need to expand trade and investment ties and encourage the use of their local currencies in payments. However, actual progress has been slow.

At present, within the BRICS grouping, there is no functional infrastructure for making payments between these countries. At this stage, the technical barriers to creating such an infrastructure are outweighed by political ones.

In addition to existing technological hurdles, efforts to create and launch alternative cross-border payment infrastructure face obstacles stemming from geopolitical factors, differing objectives of member countries, and persistent trade imbalances among EM nations.

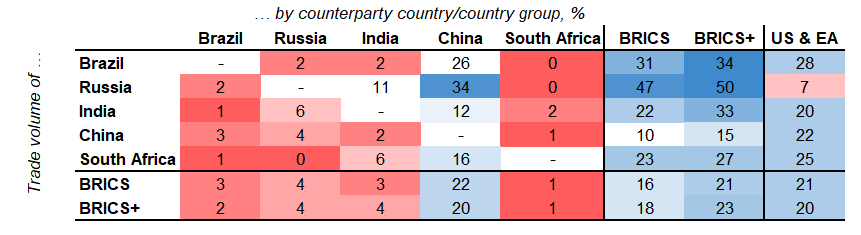

Table 1. Shares of intra-BRICS trade by partner, % of total trade volumes

* Trade volumes are calculated as the sum of exports and imports of the respective country/group of countries (rows) with partner countries/country groups (columns), expressed as a percentage of the total trade volume of the given country/country group. The BRICS+ group includes new members—Iran, Egypt, Ethiopia, the UAE, and Indonesia. Shares of trade with partners amounting to less than 10% of total trade are marked in pink; the lower the share, the darker the shade. Shares of 10% or more are marked in blue; the higher the share, the darker the shade.

Source: J. P. Morgan, Haver Analytics, IMF.

One of the first attempts to develop so-called sovereignty and “de-dollarization” of payments was the launch in 2010 by BRICS countries of the Interbank Cooperation Mechanism (ICM) to promote international payments in local currencies among the development banks of member countries. However, the actual use of the ICM for the purposes of so-called de-dollarization has been limited. As of 2024, there is no information—according to J.P. Morgan—on the signing of bilateral credit line contracts in local currencies between countries, specifically within the ICM framework.

In 2018, BRICS countries launched the BRICS Pay project—a digital payments platform in national currencies—but it remains in the early stages of discussion.

BRICS member countries (including new members—Egypt, Iran, Indonesia, Ethiopia, and the UAE) have concluded bilateral agreements among themselves for cross-border payments using national currencies. In recent years, in particular, the use of China’s bilateral swap lines with its trading partners has been increasing, as already mentioned. Outside the BRICS framework, the Asian Chiang Mai Initiative is a more advanced financing mechanism. It began as a network of bilateral swap agreements between the ten ASEAN members, as well as China, Japan, and South Korea, in response to the financial crisis of the 1990s, and later became a more structured multilateral agreement in 2010.

An analysis of trade links within BRICS shows that China is more connected with other members of the bloc than the other BRICS countries are with each other. As a result, the development of payments within BRICS primarily creates opportunities for the Chinese yuan. However, China’s capital controls reduce the attractiveness of Chinese assets for foreign investors and limit the willingness of third countries to accept payments and conduct settlements in yuan, as well as to accumulate assets denominated in this currency.

Several BRICS member countries have made progress in developing national infrastructure for digital payments—China (Alipay, WeChat Pay), India (UPI), Brazil (Pix)—and are even working on creating their own central bank digital currencies. This could potentially expand opportunities for cross-border transactions in national currencies among these countries.

Discussions on further integration and expansion of cross-border payments among BRICS countries cover issues such as payment mechanisms, types of currencies, how to implement the necessary infrastructure in practice, and how to share the costs. Concerns have arisen over integrated systems, as the bloc’s recent expansion has caused delays in developing cross-border payments. Technical barriers to integration are also compounded by the non-convertibility of certain member states’ currencies, sanctions imposed on Iran and Russia, and the unpreparedness of some countries’ central bank systems to implement such changes.

India, also a member of BRICS, is another example of relatively active use of its national currency in international transactions.

Since 2012, the Reserve Bank of India has operated a local currency swap mechanism for Southeast Asian countries—the SAARC Currency Swap Facility. In addition, in 2023, the Reserve Bank of India authorized banks from 22 partner countries, including Russia, to open Special Rupee Vostro Accounts (SRVAs) in Indian financial institutions to promote bilateral trade in national currencies. From July 2022 (when the central bank created the first mechanisms for rupee settlements) to October 2023, India’s international trade in rupees amounted to more than USD 2.5 billion equivalent—about 2.6% of India’s total foreign trade for October 2023 and just 0.23% of the country’s total trade for 2023. Nevertheless, while the share is small, it has been steadily increasing.

In addition, the Reserve Bank of India and the Central Bank of the UAE signed a memorandum enabling exporters and importers to invoice and pay in local currencies. Unofficial reports indicate that around thirty Russian banks have been authorized to open such accounts in Indian banks. However, despite attempts to increase the use of the rupee in trade payments between India and Russia, volatility in the currency remains an obstacle. As a result, Indian companies prefer other currencies—particularly the dirham—when settling with Russian energy companies. Overall, the volume of international transactions in Indian rupees remains small on a global scale.

Conclusion

Some EM countries are increasingly discussing opportunities to expand the use of local currencies in international transactions. However, real progress so far has been quite limited, with the actual relative shares of national currencies in trade operations and other payments remaining much smaller than that of the U.S. dollar.

China has achieved the most significant progress in promoting its national currency—particularly through developing the necessary infrastructure and expanding the role of swap-line mechanisms with other countries’ central banks. Some countries under international financial sanctions use local currencies for settlements as a forced measure, and once again, the central currency in this context is the Chinese yuan.

The creation and development of digital currencies present a potential opportunity for EM countries to advance cross-border payments in national currencies. However, this process is complex and requires considerable time.

Thus, while there is a trend toward increasing the popularity of local currencies in international transactions among EM countries, the process will be slow, and the U.S. dollar and the euro will continue to hold leading positions. Under these conditions, the potential for imposing sanctions by Ukraine’s key international partners will remain—although it may gradually weaken as alternative payment systems based on the national currencies of emerging market countries develop.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations