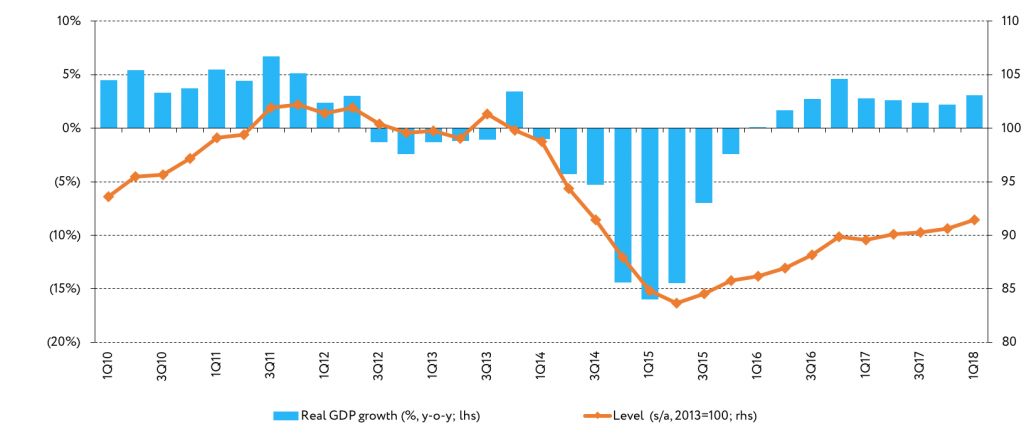

Ukraine has been gradually emerging from the economic collapse of 2014-2015. While the growth rate is respectable for a developed country, it remains low compared to developing neighbor-states. Ukraine’s economy advanced by 2.4% in 2016 and 2.5% in 2017, while emerging economies in Europe grew by 3.2% in 2016 and 5.7% in 2017. Sadly, two years into expansion Ukraine has not yet caught up with the pre-crisis level of output. Perhaps more importantly, there are surprisingly few signs of a major acceleration of economic growth just around the corner. Indeed, the rate of unemployment is stubbornly high and has been hovering at around 10 percent for the last two years.

Industrial production has been growing in fits and starts with frequent contractions rather than in a consistent manner. After an inflationary boost to government revenues, public finances appear to send bad omens with consolidated budget running cash deficit in the first quarter of 2018 after several years of healthy surpluses. Even positive signs, such as high growth in investment (18.2% in 2017) is against quite low base and is crucially dependent on imports.

Chart 1: Ukraine’s Real GDP

Source: State Statistics Service

Given that Ukraine has effectively no margin for error, where does it leave us?

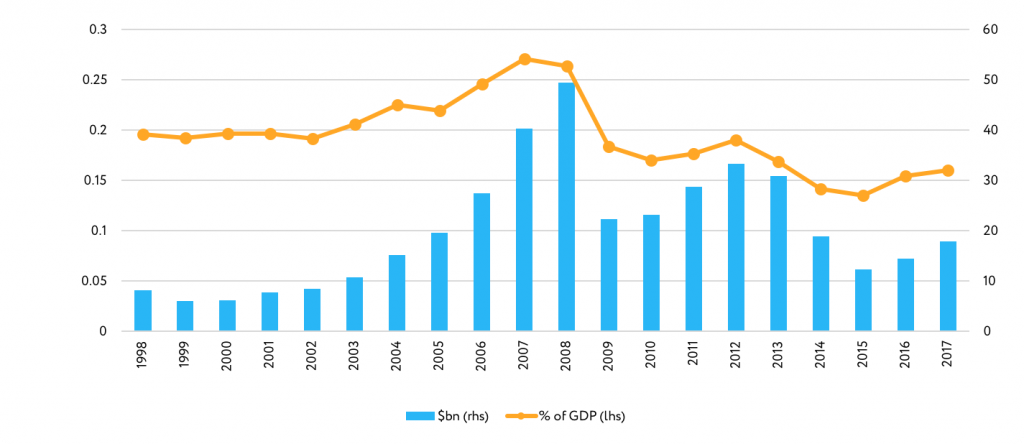

Ukraine’s progress in reforms over past several years was unprecedented compared to historical track record. However, reform progress was not sufficient to put Ukraine on a path of sustainable and strong economic growth. The country failed to attract large investments, which are needed for economic upturn. FDI inflows slid to mere 2.0% of GDP in 2017 with foreign investors naming widespread corruption and lack of trust to judiciary as major obstacles. Investment in fixed capital remained below historical average: 16% of GDP vs 20% in early 2000th and 25% recorded during 2005-2008 economic boom (recall that capital investments are the main driver for many emerging markets, including China, whose high growth rates are often cited as an example for others).

Chart 2: Investment in fixed capital to GDP

Source: State Statistics Service

Furthermore, several years of economic stability and even anemic growth should not be taken for granted. Ukraine’s economy remains dependent on global commodity markets, which have been favorable to Ukraine over past several years, but will not remain so forever. Ukraine must pay billions of dollars on its public debt in the near future and will likely have tough time borrowing from credit markets, as recent experience of Argentina and other emerging economies suggests. Though the government has received sizable financial support from the West and restructured its external debt, external financing still remains crucial to keep Ukraine afloat.

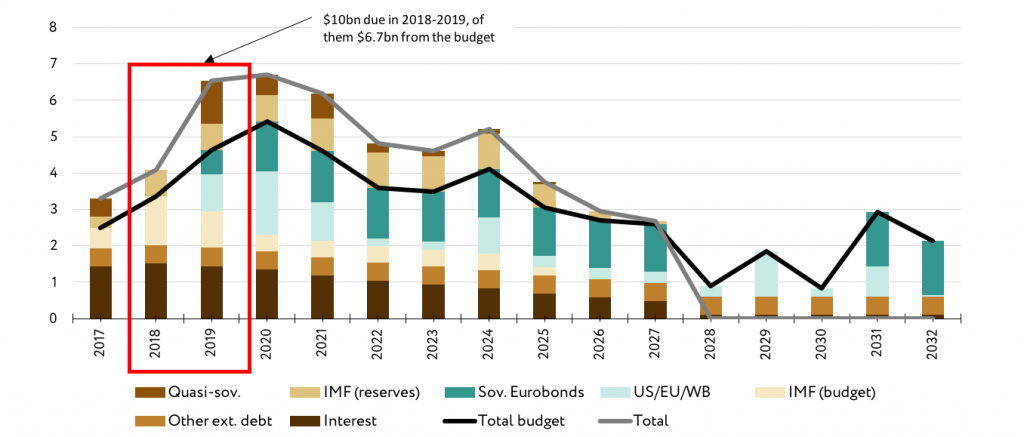

The current $17.5bn IMF program (Ukraine already received $8,4 billion in four of the planned 12 tranches) expires in March 2019, just before Ukraine enters elections’ long cycle: Presidential elections in March next year and Parliamentary elections in October. But Ukraine’s authorities don’t have time until March next year as heavy payments start soon.

Indeed, Ukraine faces more than $10 billion of external public debt repayments in 2018 and 2019, including principal and interest on external debt. Repayments to official creditors, such as the IMF, the World Bank or the U.S., account for almost two-thirds of this amount.

Indeed, Ukraine faces more than $10 billion of external public debt repayments in 2018 and 2019, including principal and interest on external debt. Repayments to official creditors, such as the IMF, the World Bank or the U.S., account for almost two-thirds of this amount. Though the authorities had enough resources to make 1Q18 repayments, external sovereign debt coming due until end-2019 amounts to sizable $8.5bn, accounting for almost half of central bank’s international reserves ($18,4bn by end-April). Without new foreign currency borrowings, the NBU reserves will slid below commonly recognized safety threshold of 3 months of imports already by the end of 2018. Continuous decline in reserves coupled with increased uncertainty on the eve of elections and unfavourable end-year foreign exchange market seasonality will likely give a rise to devaluation expectations. Pressures on the national currency will build up quickly, putting hryvnia at risk of sharp devaluation. The NBU will be forced to react with interest rate hikes, new capital and exchange controls, and other anti-crisis measures. Would these steps be effective in preventing currency crisis or not depends on many factors, including global commodity prices. In any case, anti-crisis measures will dent on already weak economic growth, which will likely undermine the current pro-EU course of Ukraine and give new ammunition to pro-Russian (and populist) forces.

Chart 3: Sovereign external debt repayments ($bn)

Source: National authorities, Dragon Capital estimates

Moreover, the government may appear on the brink of default even earlier, as the majority of scheduled external debt repayments are to be made from government’s coffers, not the central bank. The government faces $6.7bn of external debt repayments by the end of the next year . Of these, about $2bn are due already by the end of 2018, while the government’s foreign currency liquidity amounted only to $1.4bn by end-1Q18, on our estimates, including funds kept in state-owned banks. This is sufficient to meet scheduled repayments only till August-September. The government can buy foreign currency from the central bank, if it has enough hryvnias in its account. This may be an important “if” because the government’s revenue is falling behind the plan. The government may muddle through for another several months by tapping domestic dollar-denominated bonds, but will eventually find itself on a brink of default, perhaps even to official creditors such as the IMF or the US.

Does it mean Ukraine has to be bogged down in a low-growth state?

No! Ukraine still has untapped reserves for economic growth. For example, while opening land market for sale is not particularly popular among Ukrainians, it has a huge potential to benefit the economy and the people of Ukraine. It should generate fiscal revenue, increase productivity, facilitate the flow of credit, and bring in foreign direct investment. Going against public opinion is hard, but it is not impossible to change (mis)perceptions and do the right thing for the country.

Likewise, protection of property rights remains poor because of widespread corruption. While the government has invested significant resources into anti-corruption institutions, investors remain skeptical and, indeed, it is hard to expect overwhelming progress in this area until they see convictions of corrupt high-level officials. Sadly, most Ukrainians agree that the current law enforcement system has proven impotent at the task. We may debate about the optimal design of the anti-corruption court – a key requirement for the next IMF loan tranche – but the need for a new institution is clear. The public support for this new court is strong enough to outweigh the resistance of vested interests.

We may debate about the optimal design of the anti-corruption court – a key requirement for the next IMF loan tranche – but the need for a new institution is clear. The public support for this new court is strong enough to outweigh the resistance of vested interests.

Relatedly, privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is a challenging exercise in a depressed economy and ideally it should be done when the value of the property is at its peak. However, after years of abuse, few SOEs can boast strong financial positions. Waiting for the right time to do privatization may be too costly. A recently adopted law on privatization can accelerate the process and attract more buyers, which can help raise the price of SOEs offered for sale. Privatization should remove economic distortions and sources of corruption.

Ukraine continues to have high concentration of economic power in a number of sectors. These monopolies not only generate economic distortions (high prices, low productivity, etc.) but also create political risks as incumbents may try to bribe politicians to protect their rents. Sadly, in the new history of Ukraine there is hardly a successful case of breaking a monopoly. Yet, creating a more competitive environment will lead to a more dynamic economy. There are already legal prerequisites for introduction of elements of competition into energy sector (new laws on natural gas market and on electricity market). Implementation of these laws, together with keeping a single market-determined natural gas price for all consumers will not only increase competition but also likely increase production of energy as well as energy efficiency.

Finally, Ukraine still has many inefficiencies in the provision of social support – from household utility subsidies to child allowances. The funds spent on subsidies provided to people who don’t really need them, could otherwise be spent on infrastructure and/or energy efficiency, education and healthcare. However, the registry of beneficiaries of social safety net is still far from completed – despite all the time and (donor) funds allocated to it.

Concluding remarks

Today, heavy debt repayments and possible macroeconomic and currency crisis require urgent action. If these risks materialize, the government will be unable to fulfill its obligations, including social transfers to the public. This will result into a major political crisis on the eve of the elections.

At the same time, if the risks are addressed, there continue to exist a number of opportunities to accelerate economic growth. For each of these options, the government must overcome resistance of incumbents and vested interests. To succeed, the government must show resolve and “own” reforms.

Editorial board of VoxUkraine, Kyiv School of Economics

- Olena Bilan, Dragon Capital

- Yuriy Gorodnichenko, UC Berkeley

- Ilona Sologoub, KSE

- Tymofiy Mylovanov, Honorary President, KSE

- Veronika Movchan, IER

- Denys Nizalov, KSE

- Olena Nizalova, University of Kent

- Alex Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, Lehigh University

- Oleksandr Talavera, Swansea University

- Oleksandr Zholud, NBU

- Oleg Nivievskyi, KSE

- Oleksandra Betliy, IER

- Natalia Shapoval, Vice-President for Policy Research, KSE

- Volodymyr Bilotkach, Newcastle U

- Tom Coupé, Canterbury U

- Natalia Mostepanyuk, Vice-President for Finance, KSE

- Yuliya Klymenko, Vice-President for Business Education, KSE

- Olesia Verchenko, Vice-President for Economics Education, KSE

- Oleksa Stepaniuk, Data Analyst, KSE

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations