Before one suggests an aggressive fiscal consolidation to balance Ukraine’s budget, he or she should contemplate if Ukraine is prepared for another 5-10 percent decline in GDP. A sensible macroeconomic policy includes maintaining the level of public spending, increasing efficiency of government spending, improving tax collection and compliance, and borrowing from foreign sources to cover temporary fiscal deficits.

As 2016 approaches quickly, many observers increasingly wonder how Ukraine’s state budget is going to look in the coming year. The Ministry of Finance plans to release a proposal for the budget along with a new Tax Code soon. Public discussion centered on how much government spending and revenue—and consequently budget deficit—the country should have. A proposal put forth by the Parliament apparently envisions a giant deficit, at least in the short run, because expected de-shadowing of the economy cannot happen overnight.

Given limited fiscal capacity of the Ukrainian government as well as non-existent access to borrowing in foreign capital markets at the moment, some conclude that a balanced budget (with remorseless cutting of government spending) is a prudent course of action. Moreover, in order to continue cooperation with the IMF, which currently is the main source of external finance for public sector, Ukraine should keep its budget deficit within the limits stipulated in the program. There are also estimates suggesting that government spending as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) should be cut by eight percentage points.

Does this policy make sense from a macroeconomic perspective?

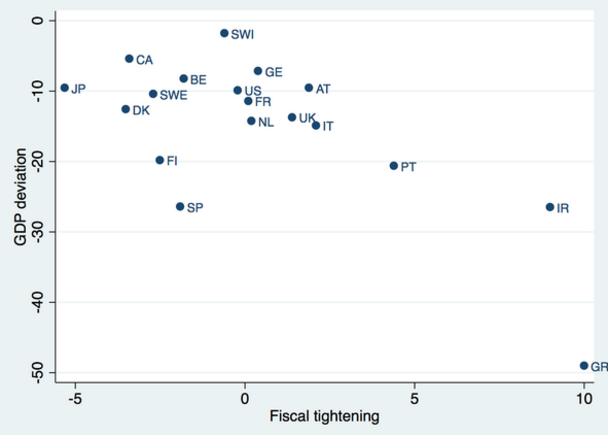

There is strong evidence that fiscal consolidation in weak economic conditions is self-defeating. The mechanics of the process is simple: a cut in government spending contracts output which reduces tax revenue which in turn forces more cuts in government spending. The Greek economy is a good example of how fiscal austerity in a contracting economy led to a collapse not seen since the Great Depression. But Greece is not unique and the lesson generalizes to other countries. In a recent post, Paul Krugman presents a clear relationship between economic performance and tightness of fiscal policy. Even if one excludes Greece, the pattern is clear: larger fiscal consolidations are associated with larger contractions of output. One might have expected that enough time has passed to learn from policy mistakes made by other countries so that current and future policy would avoid the mistakes.

Source: Paul Krugman

Yet, calls for immediate cutting of government spending continue to dominate the public debate. This is striking given what happened in other countries recently and, more importantly, in Ukraine during 2015. Specifically, earlier this year, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Ukrainian government agreed on a fiscal plan that involved a fiscal consolidation equivalent to 6 percent of GDP, a magnitude comparable to what Greece did. In March 2015, the IMF projected a 6 percent contraction of GDP in 2015. This forecast was likely based on the estimate of fiscal multiplier of approximately one: that is, a one hryvnya decrease in government spending leads to a one hryvnya decrease in GDP. At that time, I suggested that this calculation is likely to turn wrong: the multiplier is likely to be bigger (at least 1.5: a one hryvnya decrease in government spending leads to a 1.5 hryvnya decrease in GDP) and, hence, the contraction of GDP is likely to be in excess of 10 percent. Now the IMF, the government and private forecasters project 11 to 12 percent fall in GDP in 2015. These magnitudes are consistent with my predictions made earlier this year and they are clearly off from what the IMF and others forecasted. This outcome should certainly raise a red flag for those who think that a massive fiscal consolidation is going to be a “solution” to Ukraine’s problems in the short run. At minimum, one should take seriously the idea that a radical cutting of government spending can destroy macroeconomic stabilization achieved in Ukraine at a very high price.

What would be a reasonable course? First, I do not advocate for business as usual. Ukraine cannot continue to waste its precious resources on all sorts of inefficiencies in procurement of public goods. There is an enormous capacity to save public funds here via fighting corruption, competitive bidding for government contracts, outsourcing some of the public programs, making transfers more targeted, etc.

Second, expectations that a radical cutting of tax rates will pay for itself (that is, economic growth will be so strong that the tax revenue will stay constant despite lower tax rates) are unrealistic. The shortfall of tax revenue from such policies in the short run is extremely likely and given limited access to borrowing the government will be forced to cut spending, thus jeopardizing macroeconomic stabilization. Perhaps more importantly, tax reforms cannot be reduced to lowering tax rates. As suggested by Ivan Miklos, it has to be comprehensive: it should involve tax rates, tax base, compliance, and administration.

Third, Ukraine cannot raise funds domestically to cover fiscal deficits and, obviously, the National Bank of Ukraine must not print money to cover the deficits. But with successful restructuring of foreign, privately-held debt, Ukraine is improving its credit ratings and may regain access to international capital markets. It’s hard to predict at what price foreign investors would be willing to lend to Ukraine. 7-8 percent per year—close to the rate paid on the restructured debt—seems a sensible starting point. While high relative to what other government pay on their debts, this price may be acceptable if one believes in a high economic growth in Ukraine in coming years (I do believe). If private markets are unwilling to lend to Ukraine, the government should double its efforts to raise funds from public donors. Indeed, a billion dollars may seem an astronomical sum of money in Ukraine but it’s a small fraction of budgets of many Western governments or international financial institutions. Given the role Ukraine plays in geopolitics today, a few billion dollars is a small price to pay. At the same time, it is highly disturbing that the Ukrainian government cannot obtain some of the pre-committed funds from these donors because it fails to implement reforms that are very much in the interest of Ukraine.

In summary, before one suggests an aggressive fiscal consolidation to balance Ukraine’s budget, he or she should contemplate if Ukraine is prepared for another 5-10 percent decline in GDP. I doubt it. The notion that the root of all problems in Ukraine is a fiscal deficit is wrong. Macroeconomic theory and evidence is clear: before Ukraine’s economy resumes growth, running a fiscal deficit is desirable. A sensible macroeconomic policy includes i) maintaining the level of public spending, ii) increasing efficiency of government spending (and thus gradually reducing the size of public spending if the public demands to do so), iii) improving tax collection and compliance, and iv) borrowing from foreign sources to cover temporary fiscal deficits.

Tax Reform Week

Tax Reform – What’s On the Table (Pavlo Kukhta, member of the Editorial Board of iMoRe)

Pavlo Sebastianovich: Medium and Small Businesses Displaced From the Legal Field of High Tax Rates (Pavlo Sebastianovich, Civic Platform “Nova Kraina”)

Vladimir Dubrovskiy: 1-2% of GDP in Additional Revenues as a Result of a Crackdown on Simplified Taxation are Unrealistic Figures (Vladimir Dubrovskiy, RPR expert)

Tetyana Prokopchuk: Business Believes that the Priority is to Simplify the Administration of Taxes (Tetyana Prokopchuk, Vice President of Policy of the American Chamber of Commerce in Ukraine)

Robert Conrad: Tax Reform is not Simply Changing the Law (Robert Conrad, Duke University)

Anna Derevyanko: Cosmetic Changes will not Work for the Society (Anna Derevyanko, Executive Director, European Business Association)

Ukraine Needs a Radical but Sensible Tax Reform (Anders Åslund, Senior fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington and author of the book “Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It”)

Roman Zharko: Core Problem of the Ukrainian Tax System is Practice of Discretionary Use of Fiscal Mechanism to Reach the Established Revenue Targets (Roman Zharko, PhD, Tax Manager, Baker Tilly)

Tax Reform in Ukraine: How to Accomplish the Impossible (Vladimir Dubrovskiy, expert of the RPR group)

Tax Reform in the Light of Macroeconomic Stability: the NBU Perspective (Dmytro Sologub, Deputy Governor at National Bank of Ukraine, and Serhiy Nikolaichuk, Director of monetary policy and economic analysis department at NBU)

Tax Reform in Georgia: Lessons for Ukraine (Olena Bilan, Chief economist at Dragon Capital, member of the Editorial Board of VoxUkraine)

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations