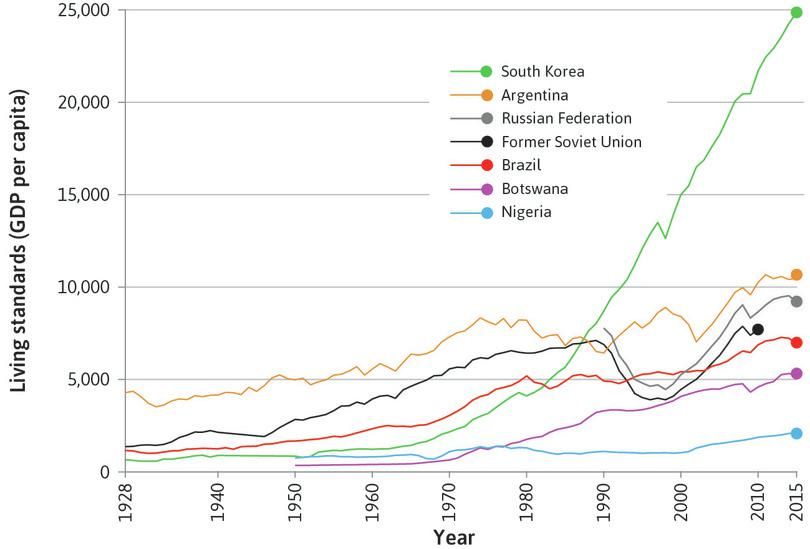

Not every capitalist country is the kind of economic success story exemplified in Figure 1.1a by Britain, later Japan, and the other countries that caught up. Figure 1.11 tracks the fortunes of a selection of countries across the world during the twentieth century. It shows for example that in Africa the success of Botswana in achieving sustained growth contrasts sharply with Nigeria’s relative failure. Both are rich in natural resources (diamonds in Botswana, oil in Nigeria), but differences in the quality of their institutions—the extent of corruption and misdirection of government funds, for example—may help explain their contrasting trajectories.

Firstly published at core-econ.org

The star performer in Figure 1.11 is South Korea. In 1950 its GDP per capita was the same as Nigeria’s. By 2013 it was ten times richer by this measure.

South Korea’s take-off occurred under institutions and policies sharply different from those prevailing in Britain in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The most important difference is that the government of South Korea (along with a few very large corporations) played a leading role in directing the process of development, explicitly promoting some industries, requiring firms to compete in foreign markets and also providing high quality education for its workforce. The term developmental state has been applied to the leading role of the South Korean government in its economic take-off and now refers to any government playing this part in the economy. Japan and China are other examples of developmental states[1].

Figure 1.11 Divergence of GDP per capita among latecomers to the capitalist revolution (1928–2015)

Jutta Bolt, and Jan Juiten van Zanden. 2013. ‘The First Update of the Maddison Project Re-Estimating Growth Before 1820’. Maddison-Project Working Paper WP-4 (January).

From Figure 1.11 we also see that in 1928, when the Soviet Union’s first five-year economic plan was introduced, GDP per capita was one-tenth of the level in Argentina, similar to Brazil, and considerably higher than in South Korea. Central planning in the Soviet Union produced steady but unspectacular growth for nearly 50 years. GDP per capita in the Soviet Union outstripped Brazil by a wide margin and even overtook Argentina briefly just before Communist Party rule there ended in 1990.

Some researchers question the validityof historical GDP estimates such as this outside of Europe, because the economies of these countries were so different in structure.

The contrast between West and East Germany demonstrates that one reason central planning was abandoned as an economic system was its failure, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, to deliver the improvements in living standards achieved by some capitalist economies. Yet the varieties of capitalism that replaced central planning in the countries that had once made up the Soviet Union did not work so well either. This is evident from the pronounced dip in GDP per capita for the former Soviet Union after 1990.

When is capitalism dynamic?

The lagging performances of some of the economies in Figure 1.11 demonstrate that the existence of capitalist institutions is not enough, in itself, to create a dynamic economy — that is, an economy bringing sustained growth in living standards. Two sets of conditions contribute to the dynamism of the capitalist economic system. One set is economic; the other is political, and it concerns the government and the way it functions.

Economic conditions

Where capitalism is less dynamic, the explanation might be that [2][3]:

- Private property is not secure: There is weak enforcement of the rule of law and of contracts, or expropriation either by criminal elements or by government bodies.

- Markets are not competitive: They fail to offer the carrots and wield the sticks that make a capitalist economy dynamic.

- Firms are owned and managed by people who survive because of their connections to government or their privileged birth: They did not become owners or managers because they were good at delivering high-quality goods and services at a competitive price. The other two failures would make this more likely to occur.

Combinations of failures of the three basic institutions of capitalism mean that individuals and groups often have more to gain by spending time and resources in lobbying, criminal activity, and other ways of shifting the distribution of income in their favour. They have less to gain from the direct creation of economic value[4].

Capitalism is the first economic system in human history in which membership of the elite often depends on a high level of economic performance. As a firm owner, if you fail, you are no longer part of the club. Nobody kicks you out, because that is not necessary: you simply go bankrupt. An important feature of the discipline of the market—produce good products profitably or fail—is that where it works well it is automatic, because having a friend in power is no guarantee that you could remain in business. The same discipline applies to firms and to individuals in firms: losers lose. Market competition provides a mechanism for weeding out those who underperform.

Capitalism is the first economic system in human history in which membership of the elite often depends on a high level of economic performance. As a firm owner, if you fail, you are no longer part of the club. Nobody kicks you out, because that is not necessary: you simply go bankrupt.

Think of how different this is from other economic systems. A feudal lord who managed his estate poorly was just a shabby lord. But the owner of a firm that could not produce goods that people would buy, at prices that more than covered the cost, is bankrupt—and a bankrupt owner is an ex-owner.

Of course, if they are initially very wealthy or very well connected politically, owners and managers of capitalist firms survive, and firms may stay in business despite their failures, sometimes for long periods or even over generations. Losers sometimes survive. But there are no guarantees: staying ahead of the competition means constantly innovating.

Political conditions

Government is also important. We have seen that in some economies—South Korea, for example—governments have played a leading role in the capitalist revolution. And in virtually every modern capitalist economy, governments are a large part of the economy, accounting in some for more than half of GDP. But even where government’s role is more limited, as in Britain at the time of its take-off, governments still establish, enforce and change the laws and regulations that influence how the economy works. Markets, private property and firms are all regulated by laws and policies.

For innovators to take the risk of introducing a new product or production process, their ownership of the resulting profits must be protected from theft by a well-functioning legal system. Governments also adjudicate disputes over ownership and enforce the property rights necessary for markets to work.

As Adam Smith warned, by creating or allowing monopolies such as the East India Company, governments may also take the teeth out of competition. If a large firm is able to establish a monopoly by excluding all competitors, or a group of firms is able to collude to keep the price high, the incentives for innovation and the discipline of prospective failure will be dulled. The same is true in modern economies when some banks or other firms are considered to be too big to fail and instead are bailed out by governments when they might otherwise have failed.

If a large firm is able to establish a monopoly by excluding all competitors, or a group of firms is able to collude to keep the price high, the incentives for innovation and the discipline of prospective failure will be dulled.

In addition to supporting the institutions of the capitalist economic system, the government provides essential goods and services such as physical infrastructure, education and national defence. In subsequent units we investigate why government policies in such areas as sustaining competition, taxing and subsidizing to protect the environment, influencing the distribution of income, the creation of wealth, and the level of employment and inflation may also make good economic sense.

In a nutshell, capitalism can be a dynamic economic system when it combines:

- Private incentives for cost-reducing innovation: These are derived from market competition and secure private property.

- Firms led by those with proven ability to produce goods at low cost.

- Public policy supporting these conditions: Public policy also supplies essential goods and services that would not be provided by private firms.

- A stable society, biophysical environment and resource base: As in Figures 1.5 and 1.12.

These are the conditions that together make up what we term the capitalist revolution that, first in Britain and then in some other economies, transformed the way that people interact with each other and with nature in producing their livelihoods.

Political systems

One of the reasons why capitalism comes in so many forms is that over the course of history and today, capitalist economies have coexisted with many political systems. A political system such as democracy or dictatorship, determines how governments will be selected, and how those governments will make and implement decisions that affect the population.

Capitalism emerged in Britain, the Netherlands, and in most of today’s high-income countries long before democracy. In no country were most adults eligible to vote prior to the end of the nineteenth century (New Zealand was the first). Even in the recent past, capitalism has coexisted with undemocratic forms of rule, as in Chile from 1973 to 1990, in Brazil from 1964 to 1985, and in Japan until 1945. Contemporary China has a variant of the capitalist economic system, but its system of government is not a democracy by our definition. In most countries today, however, capitalism and democracy coexist, each system influencing how the other works.

Capitalism emerged in Britain, the Netherlands, and in most of today’s high-income countries long before democracy. In no country were most adults eligible to vote prior to the end of the nineteenth century (New Zealand was the first).

Like capitalism, democracy comes in many forms. In some, the head of state is elected directly by the voters; in others it is an elected body, such as a parliament, that elects the head of state. In some democracies there are strict limits on the ways in which individuals can influence elections or public policy through their financial contributions; in others private money has great influence through contributions to electoral campaigns, lobbying, and even illicit contributions such as bribery.

These differences even among democracies are part of the explanation of why the government’s importance in the capitalist economy differs so much among nations. In Japan and South Korea, for example, governments play an important role in setting the direction of their economies. But the total amount of taxes collected by government (both local and national) is low compared with some rich countries in northern Europe, where it is almost half of GDP. We shall see in Unit 19 that in Sweden and Denmark, inequality in disposable income (by one of the most commonly used measures) is just half of the level of income inequality before the payment of taxes and receipt of transfers. In Japan and South Korea, government taxes and transfers also reduce inequality in disposable income, but to a far lesser degree.

Notes

[1] World Bank, The. 1993. The East Asian miracle: Economic growth and public policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

[2] János Kornai. 2013. Dynamism, Rivalry, and the Surplus Economy: Two Essays on the Nature of Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[3] Dolores Augustine. 2013. ‘Innovation and Ideology: Werner Hartmann and the Failure of the East German Electronics Industry’. In The East German Economy, 1945–2010: Falling behind or Catching Up?Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[4] Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. 2012. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group.