Soon after winning the 2014 presidential election, Petro Poroshenko presented an ambitious strategy for Ukraine’s development. Since then he has repeatedly assumed responsibility for the direction the country takes. An observer of Ukrainian politics could thus easily forget that Ukraine has a premier-presidential system of government, which usually limits the role of president to foreign policy and defence. This article presents a comparative analysis that investigates how powerful the President actually is.

Constitutional powers of the Ukrainian president in comparative perspective

Since the adoption of the constitution in 1996, Ukraine has mostly been a presidential-parliamentary republic. In 1996-2005 and 2010-2014, the president had the central role in forming (and dismissing) the government. Together with broad formal and informal powers, this made him arguably the most powerful figure in Ukraine.

The constitutional reform of 2004 (cancelled in 2010 by President Yanukovych and restored by the parliament in 2014) has seemingly changed the distribution of power within the executive by making the government accountable solely to the parliament, except for the defence and foreign affairs.

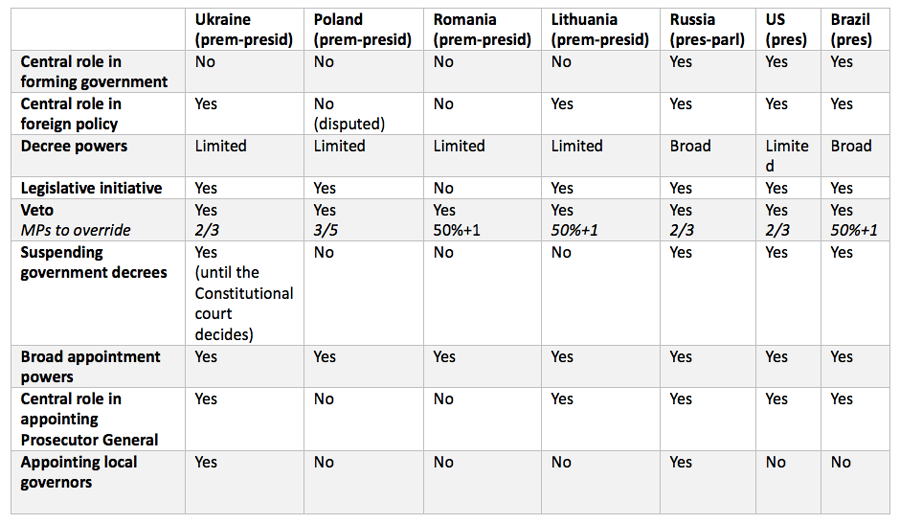

In order to see where this places the Ukrainian president in comparative perspective, Table 1 briefly considers specific presidential powers in Ukraine and other countries with relatively strong presidents.

Table 1. Presidential powers in Ukraine and in selected countries

Sources: Siaroff (2003), Taghiyev (2006), Constitute Project

For instance, presidents in other premier-presidential countries often lose the central role in foreign policy or have to share it with the government. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian president has the right to choose the ministers of defence and foreign affairs.

Another distinctive feature that assures a degree of executive power for the president is the power to appoint local governors. The president can also intervene in the executive branch by suspending the government decisions and challenging their constitutionality.

In addition, Ukraine’s president has a decisive influence over the appointment of the Prosecutor General, whereas in other premier-presidential countries the Prosecutor General is usually appointed by the parliament (Croatia), selected by other agencies (Romania) or his functions are performed by the Minister of Justice (Poland and Austria).

Finally, the veto power of Ukrainian president is stronger than in such premier-presidential countries as Poland, Romania and Lithuania.

These powers set the Ukrainian political system apart from other premier-presidential systems. Indeed, a preliminary assessment shows that the presidential authority in Ukraine may be even higher than in other premier-presidential countries with strong presidents (e.g. Poland, Lithuania and Romania).

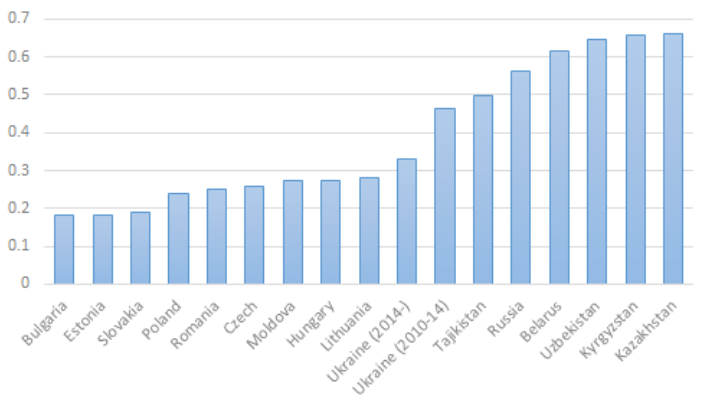

Another way to see this is to plot an index of constitutional presidential powers for Ukraine and other countries (Figure 1). Doyle and Elgie have aggregated all reported measures of formal presidential powers into one index, which allows cross country-comparison (0 is the lowest score).

Figure 1. Presidential powers in post-communist countries

Note: Other measures (Siaroff, Frye) provide similar results for Ukraine.

Post-communist countries can be neatly divided into two groups. The first group consists of relatively democratic countries, which tend to have weaker presidents. The second group is mostly formed by autocracies, which have powerful presidents. Ukraine is in the middle, seemingly undecided, as it has moved from one group to another. Currently in the first group, the Ukrainian president is one of the strongest among his counterparts in other (semi)-democratic post-communist countries.

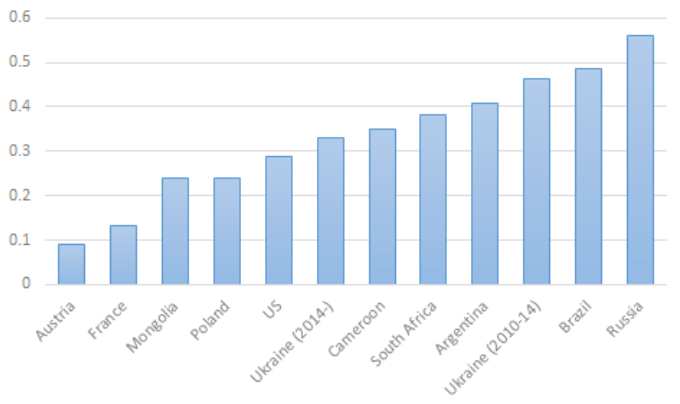

Prior to the constitutional changes, the president of Ukraine was formally as powerful as many Latin American presidents and somewhat weaker than presidents in post-Soviet superpresidential systems (Figure 2). After the changes, Ukrainian presidency has moved down the ranking. However, it is still more powerful than presidencies in other premier-presidential countries.

Figure 2. Presidential powers across the world

Such a powerful presidency in a formally premier-presidential country creates a fertile ground for within-executive conflicts and crises of the kind that we witnessed in February-April 2016 or in 2006-2010.

Beyond the constitution

One of the problems with formal measures of presidential powers is that constitutions do not always reflect the real power that presidents have. Constitutions can be vague and rather provide an outline of the distribution of power, while political circumstances and struggles modify it substantially.

France is a vivid example. Its president is constitutionally weak (scores 0.131, slightly more than Austria). If the president’s party does not hold the majority in the lower chamber of the parliament, he is essentially powerless, except in foreign policy and defence. However, if the president’s party does control the majority of MPs, the president becomes the country’s leader. In this way, French presidents follow the blueprint established by Charles de Gaulle, a charismatic personality who served as president in difficult times. Therefore, a very strong presidential institution can emerge even in a formally premier-presidential republic.

The scope for informal power dynamics is especially large in post-Soviet political systems. Their weak institutional constraints enable leaders to govern through patronage and personal rule. Hale (2005) writes that presidents in post-Soviet countries enhance their formal powers with “informal power and resources derived from the networks of patron client relations that span the state and economy”.

By increasing the prime minister’s authority, the constitutional changes of 2004 (came into effect in 2006) and 2014 have created some uncertainty as to where real power lies. However, presidency remains powerful enough to be a rallying point for interest groups. It competes with other institutions and in many cases overcomes them. For instance, President Yushchenko used his formal and informal powers to dissolve the parliament in 2007 in a legally dubious way and outplayed hostile Prime Minister Yanukovych. In 2010, after becoming the president of Ukraine, Yanukovych easily concentrated power and cancelled the constitutional reform.

In light of the latter, a formal reversion to the presidential-parliamentary system is perhaps unlikely. However, a drop in constitutional powers may not stop Poroshenko from trying to concentrate power within the premier-presidential framework. The ongoing conflict in the east of Ukraine provides a chance for the chief commander to rise above other politicians, as it underscores the central role of the president in defence and foreign policy. The very frequency of constitutional changes in Ukraine (three changes in 12 years) and weak rule of law provide further opportunities to bend formal provisions. Indeed, this is what seems to have happened during the government reshuffle in April 2016.

Coalition building powers of the president

Even powerful presidents need parliamentary support in order to implement their agenda. With this in mind, presidents all over the world routinely use a mixture of such tools as agenda power (veto and decrees), budgetary authority, cabinet management, partisan powers (control over pro-presidential factions), and informal tools (patronage, bribes etc).

The choice of tools is determined by the extent of constitutional and informal presidential powers, as well as by political context. For instance, presidents in Brazil tend to compensate weak partisan powers with considerable agenda and budgetary powers (Table 2).

In post-Soviet countries, e.g. in Russia, presidents initially preferred to use broad agenda powers and budgetary authority. However, these powers alone are not sufficient to ensure reliable legislative support (as the case of Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff reminds us). The desire to expand presidential partisan powers has resulted in the establishment of dominant party systems with controlled opposition.

In Ukraine, according to Chaisty&Chernykh (2015) presidents have used various tools. While budgetary and agenda powers are weaker than in Russia or Brazil, presidents have extensively relied on cabinet appointments and informal tools, which have “included patronage, intimidation, and bribery”. Successful coalition builders have formed legislative cartels, using the informal connections between legislators, ministries and other executive agencies. Yanukovych was especially notorious for using informal tools, such as intimidation and business perks. Recognizing the importance of partisan powers, Yanukovych tried to replicate Putin’s success in creating a dominant party system. However, Euromaidan cancelled out his efforts.

The constitutional reform has significantly decreased budgetary and cabinet management powers of the president. Moreover, in premier-presidential countries, the more powerful prime minister usually acts as the formateur of legislative coalitions. This partly explains why Yushchenko was viewed as the least efficient coalition builder among Ukrainian presidents.

Nevertheless, President Poroshenko has actively (and successfully) sought support for his legislative initiatives. His control over the largest parliamentary faction, divided opposition, broad formal and informal powers – all these factors have ensured his active role in building the parliamentary coalition. This role sets the Ukrainian political system apart from many other premier-presidential systems in Europe.

In order to win the support of parliamentary parties, Poroshenko has consistently used cabinet appointments. The importance of partisan powers and informal tools has increased after Radical Party, Batkivshchyna and Samopomich left the parliamentary coalitions. We have already witnessed and should expect further efforts to enforce strict party discipline. The efforts to increase presidential partisan power make the introduction of a fully proportional election system unlikely, given that majoritarian districts tend to favour pro-presidential candidates.

Informal tools can be especially important for securing the votes of independent and opposition MPs. This is where the president’s control over the Prosecutor General and broad appointment powers might be very useful. The president can also use those budgetary powers that he retains via his influence on the ministry of finance.

Table 2. Presidential coalition building tools in Ukraine, Russia and Brazil

Note: This is a very preliminary assessment by the author. Note of caution especially applies to informal institutions, which are by their very nature hard to measure.

The presidential ability to garner parliamentary support is now more contingent on his political prowess and partisan powers than before the switch to premier-presidentialism. However, under favourable conditions, his formal powers and informal influence seem to be high enough to persuade legislators to support his initiatives.

Conclusion

The Ukrainian president has lost some constitutional powers, but he is still one of the most powerful among his counterparts in premier-presidential countries. Significant formal and informal powers allow the president to compete with other institutions and may enable him to concentrate power even within the premier-presidential framework. While the outcome of this struggle remains uncertain, this institutional arrangement will probably continue generating instability and uncertainty until either a constitutional or a political solution is found.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations