While Parliament has the exclusive authority to pass laws in Ukraine, the President wields considerable influence over the legislative process. Among the President’s most significant powers is the ability to veto a law, thereby preventing its enactment if it does not align with the head of state’s views. However, due to imperfect legislation, the President can employ a covert tactic of indefinitely delaying his decision on laws to block them. Our investigation delved into the laws that Volodymyr Zelensky blocked during his time in office.

The Ukrainian Constitution stipulates that the President must take action within 15 days after the Verkhovna Rada passes a bill, either by signing it and making it official or by vetoing it and sending it back to Parliament with his own recommendations for reconsideration.

The method of counting these 15 days is specified in a separate ruling by the Constitutional Court. The counting of days is based on the calendar, and if the deadline falls on a weekend or holiday, it is extended to the next business day.

If the head of state fails to sign a bill within the designated time frame, the document is considered approved by default. It must be “signed and officially published” – a similar rule exists in the United States. However, the Constitution does not specify who should sign and publish bills if the President misses the deadline for signing. It also does not contain provisions that classify such conduct on the part of the guarantor as a violation or establish penalties for it. As a result, Ukrainian Presidents have allowed themselves to disregard the requirement of signing a law within 15 days. As a case in point, Volodymyr Zelensky postponed the signing of every fourth law passed by Parliament.

These actions can be seen as a form of “covert veto,” which involves intentionally delaying the ultimate decision on laws that had mixed public perception or could harm the President’s image.

How many laws did Zelenskyy veto?

Throughout Volodymyr Zelensky’s nearly four-year tenure, the Verkhovna Rada passed a total of 955 laws, out of which 912 were signed by Zelensky.

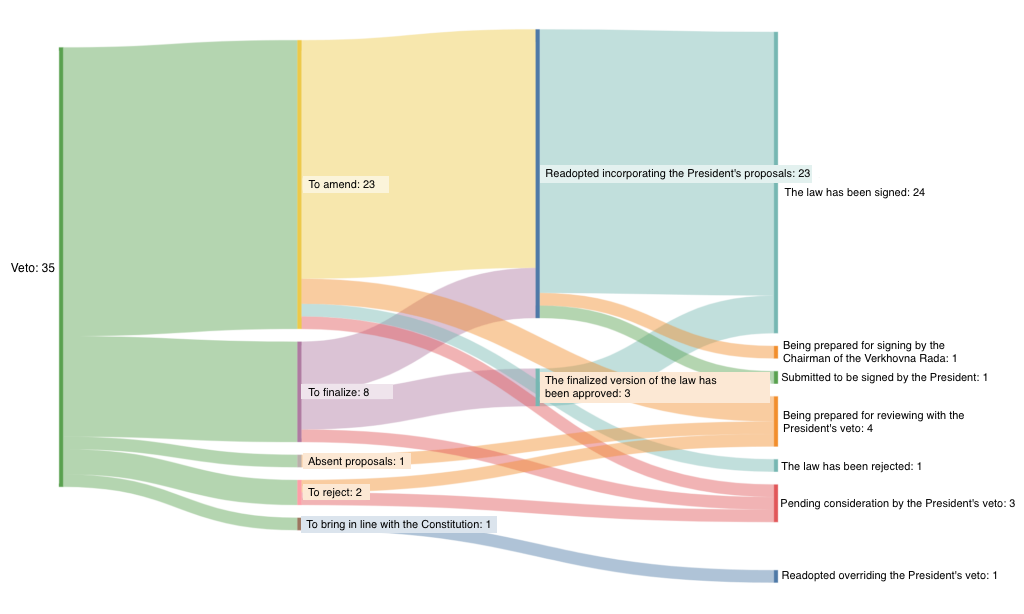

As of April 11, throughout the 9th convocation of the Verkhovna Rada, we identified 39 vetoed laws. Among these, Zelensky vetoed 34 and provided his recommendations. Another bill that sought to increase penalties for crimes committed against minors or those who have not attained sexual maturity was repealed by Zelensky. Still, his recommendations were not included in the accompanying card. Therefore, we considered a total of 35 documents. Out of these, four were proposed by MPs from the 8th convocation and vetoed initially by Petro Poroshenko; hence they were not included in our analysis.

Out of the 35 laws that were vetoed by Zelensky (as shown in Figure 1), lawmakers revised or incorporated the head of state’s recommendations into 26 of them and readopted them. Seven bills are still under consideration, while one was withdrawn and rejected (despite Zelensky’s proposals of amending it, not denying it). Parliament succeeded in overriding the Presidential veto only once to approve the law on temporary investigator commissions and special commissions of the Verkhovna Rada, which established the impeachment procedure for the President.

Figure 1. Results of the presidential veto

Data source: author’s calculations based on data from the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine of the 9th convocation (05/20/ 2019 to 04/11/2023)

The Reform Index included twelve laws that passed through the presidential veto. These laws include the law on electronic communications (+3 points); on the administrative procedures (+2 points); on virtual assets (+1.25 points); on resuming the work of the High Qualification Commission of Judges (+2 points); on changes to the rules for the dismissal of category A civil servants (+1 point); on developing the institute of starosta in Ukraine (+1 point); on enhancing criminal liability for false declaration (+2 points); on leasing property of state-owned enterprises through electronic auctions (+1 point); on punishing collaborators (+2 points); on sanctions regarding the assets of individuals (+1 point); on banning the symbols of the occupiers and pro-Russian public organizations (+0.8 points); and on developing voluntary fire protection in communities (+1.5 points).

Although Zelensky mostly complied with the Constitutional 15-day deadline for vetoing laws, he violated it in 9 out of 34 cases. This means that he vetoed those laws after the deadline had expired, which is a formal violation of the Constitution. The average time between the submission of a law for signature and its veto was 20 days because three pieces of legislation, including the law on the temporary investigative commission of the Verkhovna Rada with an amendment on the impeachment procedure, the law establishing criminal liability for violations in military procurement, and the law on supporting the Plast scout organization, were held in the President’s Office for more than two months. For one vetoed law, Zelensky took 21 days to make a decision, while for five other repealed regulations, he made a final decision within 20 days, which was also after the Constitutionally mandated deadlines.

The law on changes to the rules for dismissing category A civil servants, which eliminated the possibility of dismissing such servants on their own initiative or at the request of the Cabinet of Ministers within four months from the date of appointment of the head of the government or the relevant minister or state agency head, was vetoed by Zelensky in the shortest time possible – one day.

Why does Zelensky veto draft laws, and what does he propose instead?

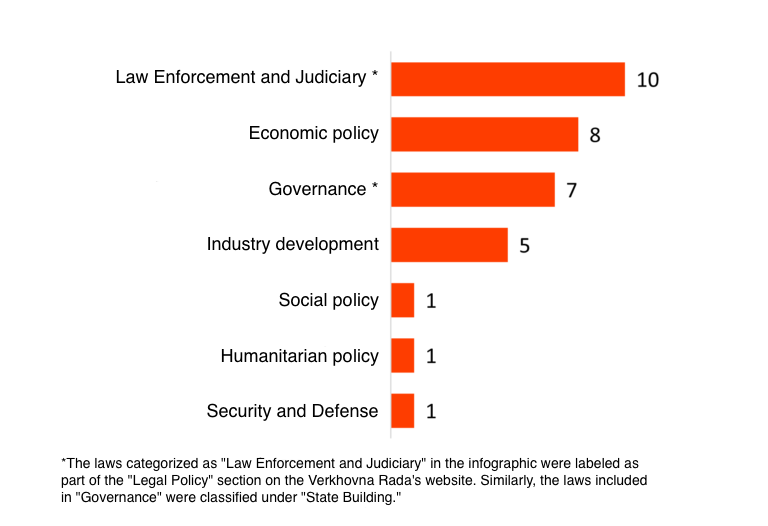

The laws that Zelensky vetoed the most were related to law enforcement, the judiciary system, governance (including the functioning of central and local authorities and interaction between citizens and the state), and economic policy.

Figure 2. Distribution of vetoed laws by rubric

Data source: author’s calculations based on data from the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine of the 9th convocation (05/20/2019 to 04/11/2023)

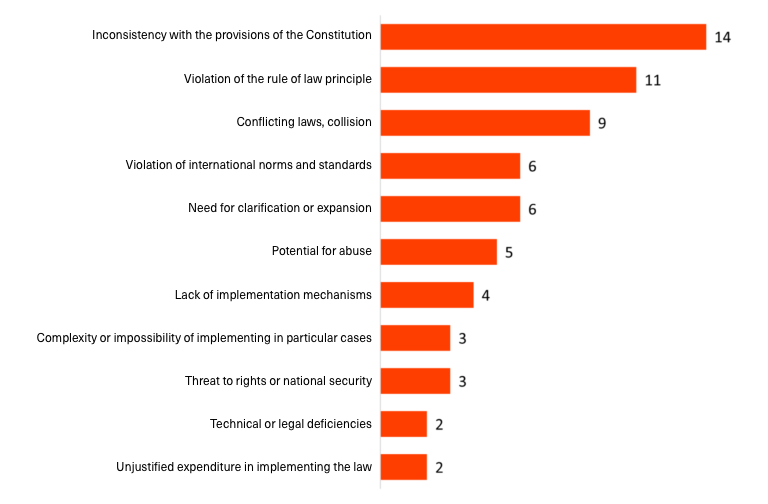

The President is required to provide formal reasons for his disagreement in the proposals to the vetoed law. In summary, his remarks (shown in Figure 3) can be categorized into three types: non-compliance with the Constitution and existing legislation, implementation difficulties, and the potential for abuse.

Zelensky typically cited one or two reasons for disapproving of a law, but some bills received more extensive comments. For example, the proposals for the law on electronic communications included seven points of commentary, addressing issues such as the law’s inconsistency with the Ukrainian Constitution, potential threats to national security, violations of the rule of law, the difficulty of implementation, and numerous technical deficiencies. The President also offered many comments on bills proposing changes to the law on preventing corruption, particularly regarding the protection arrangements for whistleblowers and on amendments to legislation concerning the High Qualification Commission of Judges of Ukraine.

In Figure 3, it can be observed that the most frequent formal reason for Zelensky’s veto of laws is their inconsistency with the provisions of the Constitution, which accounts for 40% of his proposals (14 out of 35).

Figure 3. Veto reasons by frequency of mention in the President’s proposals to the law

Data source: author’s calculations based on data from the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine of the 9th convocation (05/20/2019 to 04/11/2022)

MPs initiated the majority of vetoed laws (30). This is unsurprising given that people’s deputies proposed most of the legislation in the Verkhovna Rada of the 9th convocation. Zelensky repealed seven laws exclusively proposed by MPs from his own Servant of the People faction and two laws initiated by Batkivshchyna faction MPs. Other vetoed laws were written by MPs from two or more factions, and three were proposed by MPs from the previous convocation. In addition, Zelensky repealed two laws submitted by the Cabinet of Ministers and two of his own bills.

Although a presidential veto prohibits implementing a law passed by the Verkhovna Rada, it does not necessarily mean starting work on it from the beginning. During his nearly four-year term, Zelensky only recommended complete rejection of the vetoed laws twice, and both of these documents are still under parliamentary review. Instead, he proposed modifications to two-thirds of the vetoed bills, such as amending some parts of the text, rearranging it, or removing specific provisions. In nine instances, the President suggested the lawmakers finalize the law according to the comments and resubmit it to Parliament for reconsideration.

Decisions postponed “for later”

As of April 11, the President had put his signature on 912 laws passed by the Parliament of the 9th convocation.

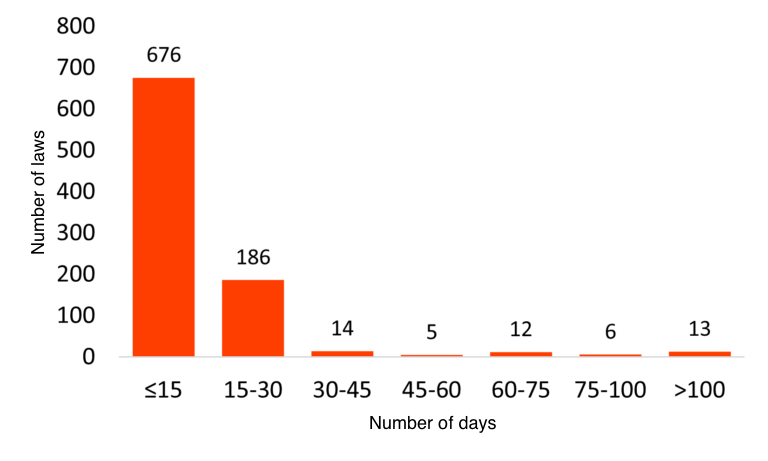

The average duration between the submission of a law to Zelensky for signature and its signing is 15 days, which generally falls within the deadline established by the Constitution.

In 236 instances, which amounts to one-fourth of the cases, the President breached the timeline stipulated by the Constitution, thus formally violating the Fundamental Law.

Figure 4. Distribution of laws by waiting time for the President’s signature (days)

Data source: author’s calculations based on data from the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine of the 9th convocation (05/20/2019 to 04/11/2022)

Thirteen laws hold the record for the longest waiting time, with the President taking three to six months (101 to 332 days) to sign them. The two laws that took the longest to be signed were proposed by Zelensky, three by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, and eight by MPs. Most of these laws (four) are related to economic policy, and two are ratifying international agreements, including a credit agreement.

Four laws, which significantly impacted different areas, were added to the Reform Index after being signed by Zelensky. These include the amendments to the Code on Bankruptcy Procedures, which imposed a moratorium on the bankruptcy of budget-funded institutions (it took 124 days to sign); the law on state registration of human genomic information (115 days of waiting); the law on the protection of state information resources (105 days of waiting), and the law on social and legal protection for political prisoners, prisoners of war, and their families (104 days of waiting).

Figure 5. Top-13 laws with the longest waiting time for the President’s signature

Data source: author’s calculations based on data from the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine of the 9th convocation (05/20/2019 to 04/11/2022)

As of April 11, 32 laws were awaiting the signature of Volodymyr Zelensky. However, he has kept more than two-thirds of them (23 statutes) pending for much longer than the timeframe established by the Constitution.

The amendments to the Budget Code, which aimed to allocate extra funds for road construction, have been pending for over three years, waiting for Zelensky’s signature. Although they were approved by the Verkhovna Rada and submitted to the President for signature on January 21, 2020, they have now become irrelevant and are unlikely to be signed.

Six laws have been waiting for the President’s signature for over two years:

- amendments to the law on temporary investigative commissions and temporary special commissions of the Verkhovna Rada;

- amendments to the law on ensuring the rights and freedoms of citizens and the legal regime in Ukraine’s temporarily occupied territories, which should resolve the issue of access of residents of the temporarily occupied territories to courts in Kyiv;

- amendments to the Verkhovna Rada Regulations regarding the publication of its decisions;

- amendments to the Criminal Code enhancing responsibility for crimes against journalists;

- amendments to the legislation regarding renewal of the unified procedure for calculating convocations of local councils;

- amendments to the law on the National Police expanding the powers of rectors of internal affairs universities.

Nine laws have been waiting for over a year for the President’s signature, and an additional nine bills have been delayed in the Office of the President for up to one year. The last on the list of the “slowest” laws is the urban planning reform law, No. 5655, which was intended to establish a system of urban planning control but was met with criticism from activists and local authorities.

However, explanations for the delay in approval or veto of laws by Volodymyr Zelensky or his team are rarely provided. There have been few instances of explanation. One time, the Office of Access to Public Information of the President’s Office declined to provide information, citing inconsistency with the law On Access to Public Information. On another occasion, Ruslan Stefanchuk, the first vice-speaker of the Verkhovna Rada, attributed the delay in signing the law on people’s power through the all-Ukrainian referendum to “internal approval procedures” in the Office of the President. He added that the President does not have the right to veto a law after the fifteen-day period specified by the Constitution. However, as mentioned earlier, Zelensky has violated this provision of the Fundamental Law nine times.

“People’s veto” does not work: which laws cause opposition from the public and how Zelensky reacts

Finally, we have undertaken an investigation into which laws Ukrainians oppose and whether the President takes into account public opinion. To accomplish this quickly, we examined the legislative initiatives against which Ukrainians submitted petitions.

We found nearly a hundred petitions calling for a veto relating to fifty different laws and bills. In some cases, multiple petitions were signed by Ukrainians against the same document.

Most petitions submitted to the President failed to meet the required threshold of 25,000 votes for consideration. Upon reviewing the unsuccessful appeals, we noticed a common trend: many citizens resorted to using accusatory language and bold statements without providing substantive reasoning for their disagreement. Furthermore, filing multiple petitions against the same draft law diluted the voices of those who dissented.

Do well-crafted petitions with over 25,000 signatures guarantee that Zelensky will heed the public’s demands? The short answer is no, not really. In fact, only four out of 94 registered petitions met these criteria.

One of these petitions requested the veto of law 8271, which aimed to increase the punishment of service members. Critics of the law argued that it gave commanders excessive authority to discipline military personnel and imposed harsh penalties for insubordination. Although Zelensky eventually signed the law on January 21, 2023, after a delay of 42 days, he did respond to the petition on December 15, 2022.

A petition was also created urging for the vetoing of law 7251, which sought to amend the labor relations laws to remove the obligation of employers to pay workers their average wages while in the service. In response, Zelensky pointed out that the time limit for vetoing the law had already passed and advised that the issue of providing proper support to the military be brought to the Cabinet of Ministers instead (the response to the petition was published in September, more than two months after the law was signed).

The petition that demanded the repeal of the Istanbul Convention’s ratification met the required number of votes for consideration. The Convention became the record holder for the number of petitions submitted against it. Zelensky responded to the petition, but it did not impact the Convention’s ratification. The response to this petition was also published after the law was signed.

The petition calling for the veto of law 5655 on urban planning reform garnered the most public attention and support with over 42,000 votes. Despite the significant public outcry, Zelensky failed to respond to the petition, as he was required to do within ten days of its submission. Additionally, the President has refrained from signing or vetoing the bill for over 100 days.

It can be inferred that President Zelensky has not complied with any petitions from citizens to veto a law. However, when an initiative generates negative attention, the President appears to take a wait-and-see tactic, possibly anticipating that the public will eventually lose interest in the issue.

Conclusions

Throughout his term, Volodymyr Zelensky has exercised his veto power 35 times, typically adhering to the 15-day limit prescribed by the Constitution for vetoing laws and proposing amendments. However, he has violated this provision on nine occasions.

The President’s vetoing of laws is mainly due to their non-compliance with the Constitution, existing laws, or the potential for abuse. Most of the bills that elicited comments from Zelensky were introduced by MPs, with the majority of laws vetoed by the President originating from the Servant of the People faction.

Zelensky has violated the fifteen-day deadline for signing laws on 25% of occasions. In many cases, he has employed a tactic known as the “covert veto” by intentionally delaying the signing of laws criticized by the public. Some signed laws have remained in the President’s Office for as long as six months. As of April 11, 32 laws are awaiting the President’s decision, 23 of which have already passed the deadline for signing. The delay has been so long for some laws that they have become irrelevant.

The current President has yet to heed the public’s call for vetoing laws. We found four petitions calling for vetoing laws that garnered over 25,000 citizen votes. Although three of these petitions received a response from Zelensky, it did not prevent the laws from being signed. As for the fourth petition, the President failed to respond within the ten-day deadline, and the status of Bill 5655, which the petition sought to veto, remains uncertain after more than 100 days.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations