Companies that adhere to gender diversity in senior management are generally more efficient and demonstrate stronger financial performance.

Studies have shown that companies with the highest levels of gender diversity achieve, on average, 28% higher profitability than their competitors. Moreover, corporations with over a quarter on executive committees are ten times more profitable than those with exclusively male boards of directors.

Despite the positive effects of involving women in management, the global share of women in leadership positions remains low (23.3%). This situation is not due to lower qualifications among women but rather to stereotypical attitudes during hiring and career advancement processes. Therefore, both companies and national governments are implementing measures to ensure equal opportunities for women and men, including in the labor market. In the European Union, this issue is regulated by the “Women on Boards” Directive, which sets quotas for women at 40% among non-executive directors and 33% among executive and non-executive directors combined. These EU-level measures are temporary and intended to act as a catalyst for change on the path to achieving gender equality.

In Ukraine, in 2021-2022, women held 21.3% of leadership positions in the largest companies by turnover. A 2021 study by Vox Ukraine revealed that women occupied leadership positions in only 26.7% of Ukrainian enterprises. Moreover, in senior management of large Ukrainian companies, women accounted for only 15.9%, indicating a significant decline in the share of women in leadership as company size increases (see Figure 1). Thus, given Ukraine’s path toward European integration, there is room for improvement in this area, and global and European experiences can serve as valuable guides on this journey.

Figure 1. Share of men and women in leadership positions by company size, %, as of January 1, 2021

Data source: State Statistics Service

Why is gender diversity in senior leadership important?

The need to achieve diversity, including gender diversity, among members of company boards is supported by numerous studies demonstrating its positive effects, such as economic efficiency, increased profitability, enhanced innovation, and improved internal company policies.

Research has shown that companies with higher levels of gender diversity engage in broader research and development activities, achieve better overall innovation performance, and obtain more patents. Companies recognized as innovators are often those with a greater number of female directors. Consequently, involving women in management enhances a company’s ability to foster innovation and creativity, positively impacting financial performance.

When a board comprises diverse perspectives and experiences, it can consider a broader range of ideas and develop more options for problem-solving. Diverse boards are more likely to explore alternative and entirely new approaches to addressing challenges, helping companies maintain a competitive edge in the market.

Studies indicate that involving women enhances the quality of board discussions, as diverse perspectives increase the amount of information available for analyzing and resolving complex issues. As a result, gender-diverse teams are 15% more likely to outperform their competitors in terms of profitability.

Experts from the Peterson Institute for International Economics have published similar findings. Based on an analysis of economic performance indicators for 21,980 companies across 91 countries, they found that companies with more than 30% women in leadership positions achieve a net profitability 15% higher than companies with no women in top management. Notably, even having at least one woman on the board is sufficient to make a significant impact. This correlation can be explained either by the benefits of eliminating discrimination or by the fact that involving women enhances the diversity of skills within the company. Based on these findings, the authors predict that companies engaging women directors will experience higher profits.

The financial benefits of gender diversity are also confirmed by the International Labour Organization (ILO), based on an analysis of leading companies in 70 countries. Companies with 30-40% women on their boards are more likely to improve their business performance. In light of this, the ILO recommends that at least 30% of board members should be women.

Despite the proven advantages of a balanced gender composition on boards of directors, women remain underrepresented in senior leadership: they hold less than a quarter of board seats globally (23.3% in 2023, an increase of 3.6% from 2022). Among board chairs, the representation is even lower—only 8.4% of boards are chaired by women, and just 6% of chief executive officers worldwide are women. In 2021, the highest proportion of women on boards was in Europe and North America, with 34.4% and 28.6%, respectively. The lowest representation of women leaders was in the Asia-Pacific region (13.3%) and Latin America (12.7%) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of women on boards of directors worldwide: Regional distribution, %

Gender Equality Index

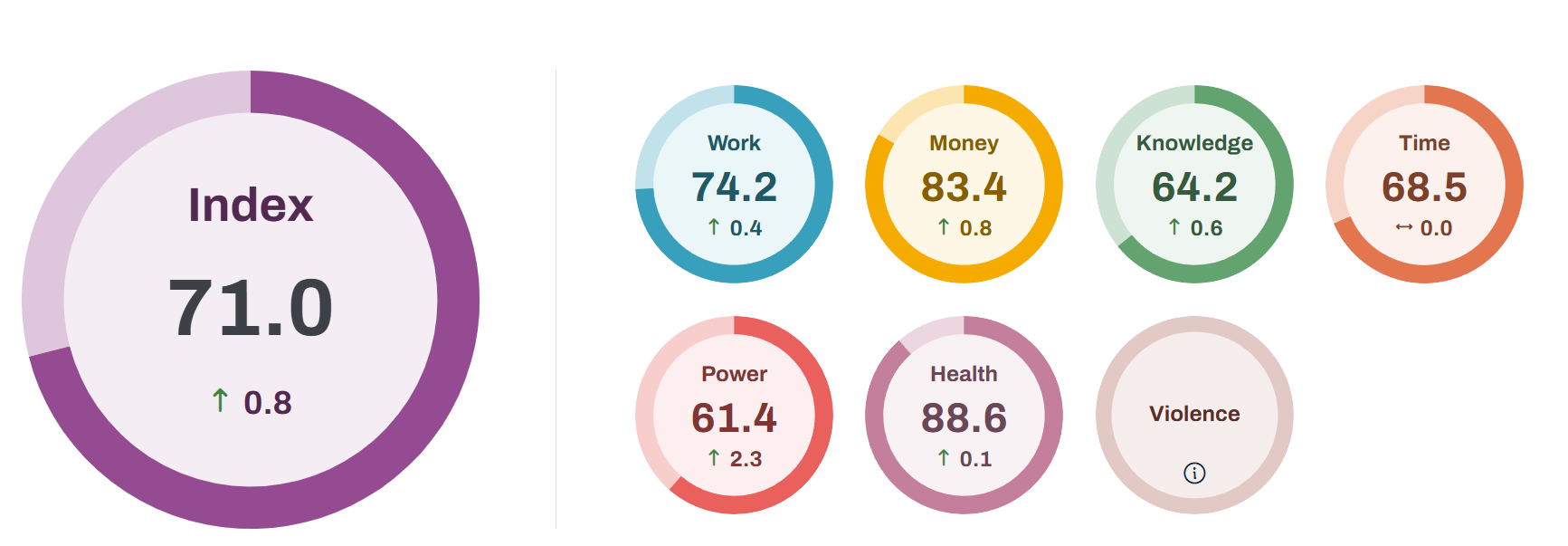

One of the tools that allows for regular measurement of progress in gender equality across European countries, including in the business sector, is the EU Gender Equality Index, developed by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). The Index evaluates EU countries based on six main indicators: work (engagement of women and men in the labor market; working conditions); power (representation of women in politics and economics); knowledge (access to education); money (economic and financial resources); time (care work and social activities); and health (access to healthcare and healthy lifestyles). Additionally, the European Institute for Gender Equality measures the prevalence of the most common documented forms of violence against women, although these data are not included in the Index. The Index ranges from 1 (complete inequality) to 100 (complete equality).

Ukraine has joined the adaptation of the methodology for the European Gender Equality Index, including the collection and calculation of relevant indicators, for the first time. This work became possible thanks to the collaboration between the Ukrainian Women’s Fund and the State Statistics Service, with the support of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration of Ukraine and the Office of the Government Commissioner for Gender Policy. The Index is calculated using the European methodology. However, considering the challenges posed by the war in Ukraine, including limited access to or the complete absence of certain data, the expert team adapted the calculation methodology with professional support from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE).

The development of the Index is part of the project “Network of Gender Think Tanks: Capacity Development for Advanced Policy Design, Impact Assessment, Strategic Advocacy, and Specialized Policy Communications,” funded by the European Union. Vox Ukraine contributed to data collection for calculating the economic impact indicator for women, specifically gathering information on the share of women in supervisory boards and boards of directors of Ukraine’s largest companies by turnover for 2021-2022. According to EIGE’s methodology, data from two years prior is used to calculate the Index. The data collected by Vox Ukraine will be included in Ukraine’s Gender Equality Index, which is set to be published in 2025.

According to the latest data, the average Gender Equality Index score in European Union countries is 71%. The highest level of gender equality in the EU is observed in the field of health (88.6 points), particularly in the subcategory “access to healthcare” (97.6 points). The lowest score remains in the area of women’s power, especially in the dimension of “economic decision-making” (57.6 points).

Figure 3. Gender Equality Index scores in the EU as of 2024

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality

Note: The “Violence” section is not included in the final calculation of the Index.

One of the indicators considered in calculating women’s economic influence is the proportion of women members on supervisory boards and boards of directors of the largest publicly traded companies. In Ukraine, data on the gender representation of women in the largest companies by turnover, collected by analysts from Vox Ukraine, were used for the experimental calculation of the Index.

According to the latest Index data, the share of women in leadership positions in the European Union is 34% (in the European Economic Area, which includes the EU along with Iceland, Norway, and Liechtenstein, this figure is slightly higher at 44.5%). Compared to 2013, the share of women on boards of directors in European companies has nearly tripled (see Figure 4). Representatives of the European Institute for Gender Equality attribute this to the active implementation of quotas for women in European companies. However, the growth rate of women’s representation has slowed since 2019, making it difficult to predict when (or if) parity will be achieved.

Figure 4. Share of women in leadership positions on supervisory boards and boards of directors of the largest public European companies, %

Data: Gender Equality Index (2013-2024)

Ukraine slightly lags behind the average indicators across Europe. Only 21.3% of women hold senior leadership positions, such as board members, supervisory board members, or directors, in 48 out of the 100 largest companies by turnover that provided data. Furthermore, in 13 of these companies, all leadership positions are held by men, meaning women are entirely absent from top management. Despite this, Ukraine’s figures significantly surpass those of certain European countries, such as Estonia, Cyprus, Hungary, and Romania (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Gender distribution of board members in the largest public companies (for Ukraine – largest by turnover), % of supervisory boards or boards of directors

Data: Gender Equality Index, country indicators for 2024

How European countries address gender gaps: Lessons for Ukraine

The Index highlights that European companies still have room to progress toward achieving gender parity among directors and supervisory board members of the largest companies. As of 2024, the best gender balance in the European Union is observed in France, Denmark, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and Ireland. Outside the EU, Norway and the United Kingdom also show strong performance (44.3%). Significant gender imbalances remain in Estonia (where only 13% of leadership positions in the largest public companies are held by women), Hungary (11%), and Cyprus (9%).

Research into national policies aimed at achieving gender equality shows that low levels of women’s economic influence are often due to governments prioritizing the elimination of gender gaps in other areas. Typically, legislation governing gender policies initially focuses on addressing and preventing gender-based violence, while the development of targeted policies to increase women’s representation in leadership positions has long been a secondary priority.

Implementing the EU Directive “Women on Boards” requires governments to reassess national mechanisms and introduce tools to promote gender parity. The Directive sets clear benchmarks: by 2026, at least 40% of supervisory board members must be women. Companies that fail to meet this requirement will need to justify deviations or face fines. This decision marks a significant step forward for many EU member states, where, despite gradual changes, leadership positions have traditionally been dominated by men.

European governments are employing two key models to achieve gender parity in senior company leadership. The first, strict approach involves mandatory gender quotas for top company leadership. The second relies on softer measures, such as recommendations for companies, changes to internal corporate environments, the development of social policies, and the promotion of female leadership.

One of the most compelling examples of successfully implementing gender quotas and penalties for failing to meet requirements for women’s representation in company leadership is Norway. In 2003, the Norwegian government introduced a 40% gender quota. This move sparked heated debates within the business community. Company executives expressed concerns that quotas might lead to discrimination against men. They also feared that women might be perceived as having attained leadership positions solely because of quotas rather than their own merits, potentially resulting in even greater discrimination against women. However, the economic impact of implementing quotas counters these concerns. Today, nearly 44% of leadership positions in publicly traded companies in Norway are held by women, and with increased female representation, the profitability of these companies has risen by 20%.

Over time, the practice of gender quotas for top companies spread across European Union member states. As of 2024, eight EU member states (France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Portugal, Germany, Austria, and Greece) have enacted legislation mandating gender quotas for boards of directors, with penalties for non-compliance. Companies in France, Italy, and the Netherlands have already reached the 40% female representation level required by the EU Directive. Other countries have also significantly increased women’s representation in leadership positions after implementing quotas (see Figure 6). Given the positive effects of mandatory quotas, the need for strict measures is also being discussed in other European countries, such as Sweden and Estonia.

Figure 6. Increase in women’s representation in the leadership of public companies in European countries following the introduction of mandatory gender quotas, %

Another model for addressing the gender gap in leadership is the implementation of “soft” regulatory mechanisms, which do not impose strict penalties for failing to meet legislative recommendations on women’s representation on boards. Some countries adopt “comply or explain” policies, where quotas for companies are merely recommendations, and non-compliance does not result in negative consequences. However, companies are required to publish reports on their efforts to achieve gender parity in leadership, including successes and failures of such policies, and outline plans to meet the established recommendations. Such practices are in place in Spain, Finland, and Denmark.

Data shows that soft, voluntary measures can also be effective. Proponents of this approach argue that it provides companies with more time to develop the skills of women, ensuring that leadership positions are filled by qualified professionals. Spain and Denmark have surpassed the 40% mark for women’s representation on boards of directors, while Finland has achieved 39%, which is close to the EU Directive requirements. However, the soft approach is most effective when combined with progressive social policies.

The state can encourage women to participate in leadership processes by reforming the social security system. Even in developed societies, women are still often perceived primarily as homemakers, mothers, and wives. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted that women tend to assume the majority of family responsibilities, often at the expense of their careers. Therefore, it is essential to implement policies that help balance family responsibilities and career development. Such measures include parental leave, equitable sharing of childcare duties between men and women, expanded childcare services, and the development of affordable and flexible daycare networks. An example of the successful implementation of such approaches is Sweden, which demonstrates strong gender parity in senior leadership positions (37% as of 2024).

At the company level, soft measures can include corporate policies to expand opportunities for women, including career advancement. The “glass ceiling“—invisible barriers preventing women from reaching higher positions—still exists, particularly at the upper levels of corporate hierarchies. These barriers can take various forms, including gender and racial stereotypes, biases against women’s management styles, ideological obstacles, and institutional factors within companies. These may include a lack of mentorship and networking opportunities and systemic discrimination in hiring and promotion processes.

To overcome the “glass ceiling,” leading European companies are implementing innovative management and recruitment practices. Mentorship and training programs for women, aimed at preparing them for leadership roles, are becoming increasingly common. These programs provide women with guidance, support, and opportunities for networking.

Another mechanism is the modernization of recruitment systems. One effective approach to unbiased hiring is “blind” hiring, where identifying information, such as gender, is removed from candidates’ resumes before preliminary reviews. Structured interviews are used at the interview stage, where all candidates are asked the same questions in the same order, helping to eliminate or at least reduce biases. For instance, in the largest companies in Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, transparent recruitment systems with open competitions for leadership positions are in place. This approach minimizes gender bias and promotes women’s representation even in industries traditionally considered “male-dominated.”

Ukrainian companies are also actively participating in these processes. According to the Corporate Equality Index report, in 2021, 57.4% of large companies in Ukraine adhered to workplace equality policies (or anti-discrimination policies), and 80.9% of surveyed companies had staff responsible for promoting gender equality. Additionally, 52% of these companies conducted mandatory annual training sessions to raise awareness of diversity and inclusion, while 19% offered their own courses on these topics. The ongoing martial law in Ukraine has also led to a reduced share of men in the labor market, increasing interest in involving women in professions traditionally considered male-dominated. As a result, there has been a rise in retraining courses and programs for women, including state-supported initiatives.

European practice demonstrates that effective social policies enhance the impact of measures companies adopt to achieve gender diversity. Reforms in social policy are equally crucial for Ukraine, as they can help shift away from the still prevailing belief that women cannot balance career growth and family responsibilities. Currently, Ukraine’s family policy primarily focuses on increasing birth rates, while issues such as family well-being, equitable distribution of responsibilities within the household, and opportunities for both spouses to achieve professional fulfillment largely remain unaddressed by the state. For instance, it was only in 2021 that legislation was introduced allowing fathers to take a two-week leave following the birth of a child without requiring proof of the mother’s employment. Previously, such leave was possible only if the mother officially delegated her responsibilities to the father.

If a woman is a single mother, her career advancement becomes even more challenging. One potential solution to this issue lies in reforming preschool education. According to a recently adopted law, new forms of preschool education are expected to be introduced in Ukraine soon. One such form is the family kindergarten, which would accept children from birth. Additionally, the state guarantees that nurseries will admit children as young as three months old (though it remains unclear who will work with such young children). The law also establishes a guaranteed amount of free preschool education time—up to 11 hours a day. Considering that a standard workday lasts 8 hours, this timeframe is sufficient for parents to work full-time and still have time to pick up their children.

In addition to creating family-supportive infrastructure, progress in achieving gender parity will also be facilitated by introducing gender quotas in companies, even without penalty enforcement. Similar proposals have already been submitted to Parliament. MPs suggest introducing, as a temporary measure until 2030, a requirement for at least 40% representation of one gender on the supervisory boards of state-owned and municipal enterprises, banks, and joint-stock companies. These proposals align with the goals of the EU Directive and the European Union Gender Equality Strategy 2020-2025. We hope this draft law will be adopted.

Conclusions

In the context of Ukraine’s progress toward European integration, the issue of gender diversity on the supervisory boards of the largest companies is particularly relevant. Drawing on European experience, introducing quotas emerges as the most effective way to address gender disparities. The EU’s experience highlights the success of such measures: countries with gender quotas have achieved women’s representation in leadership roles at levels of 35% or higher. Numerous studies confirm that increasing gender diversity in leadership benefits companies: a higher proportion of women in top management leads to increased profits and innovation. Thus, companies should be encouraged to develop internal corporate policies that support women’s advancement to leadership roles.

In Ukraine, an adequate institutional framework to help women effectively balance career growth and family responsibilities is still lacking. Therefore, effective strategies to address gender gaps should also encompass measures in the social policy domain, such as expanding access to daycare and nursery services, introducing flexible work schedules, and more.

Disclaimer. This publication was made possible with the support of the European Union as part of the project “Network of Gender Think Tanks: Capacity Development for Advanced Policy Design, Impact Assessment, Strategic Advocacy, and Specialized Policy Communications,” implemented by the Ukrainian Women’s Fund. The content is the sole responsibility of the NGO Vox Ukraine. The information provided does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union or the Ukrainian Women’s Fund.

Appendix

Table 1. Gender quotas for companies in European Union countries

| Country | Year of implementation | Percentage of women to be implemented in boards of directors or leadership | Sphere of application | Sanctions for non-compliance |

| France | 2011 | 40% | Public companies with more than 500 employees or revenue exceeding EUR 50 million | Penalties; cancellation of fees for directors of companies that fail to comply with legal requirements |

| Italy | 2011 | 33% | Publicly traded companies | Penalties (starting from EUR 20,000); annulment of previous appointments to leadership positions |

| Belgium | 2011 | 33 % | Public companies and state-owned enterprises | Sanctions for leadership: loss of position for a newly appointed or reappointed leader if they do not belong to the least represented gender; if the situation does not change within a year, all benefits and compensations for board members are suspended until the defined share of women is achieved |

| Netherlands | 2021 | 33% | Publicly traded companies | The appointment of a board that does not meet quota requirements is declared invalid |

| Greece | 2020 . | 25% | State-owned enterprises and public companies | Penalties |

| Portugal | 2017 | 20% from the first elective general meeting after January 1, 2018, and 33.3% from the first elective general meeting after January 1, 2020 | Publicly traded companies | Penalties |

| Austria | 2011; 2018 | 25%, since 2018—30%. The quota applies only to supervisory boards | State-owned enterprises, companies listed on the stock exchange since 2018, and companies with more than 1,000 employees | A member of the supervisory board elected in violation of the quota is not legally recognized as an appointed member of the board and has no voting rights |

| Germany | 2016 | 30% | Public companies (since 2021, quotas have been applied to companies with boards of directors consisting of more than 3 members) | Fines, annulment of previous appointments to leadership positions |

| Spain | 2007 | 40% | Public companies | No sanctions; quotas are of a recommendatory nature |

| Denmark | 2013 | 40% | Public companies | No sanctions; quotas are of a recommendatory nature |

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations