The road to Ukraine’s recovery will depend on securing the nation’s borders and restoring normal shipping lanes to Asia, Europe, and Africa. Even when peace is achieved, the task of rebuilding the country’s economy will be immense. This column contributes to a growing literature on trade and foreign direct investment in Ukraine. Before the war began, Ukraine had become an important exporter, particularly in agro-food products. In the aftermath of war, the EU’s role in Ukraine’s economic recovery – as well as its ongoing legislative and institutional reforms – will be essential.

More articles about rebuilding:

Few questions are more important to the future of Ukraine’s economy than how to get trade back on track after being derailed by the brutal Russian invasion. Of course, much depends on securing Ukraine’s borders and establishing unfettered restoration of normal shipping lanes to Asia, Europe, and Africa. But even after a durable peace is attained, the task of rebuilding the country is a challenging one, as discussed in the just published book Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies (Gorodnichenko et al. 2022), to which we have contributed a discussion of trade and foreign direct investment. Given the highly educated labour force, Ukraine has much to offer, particularly as it attracts back the war-time diaspora.

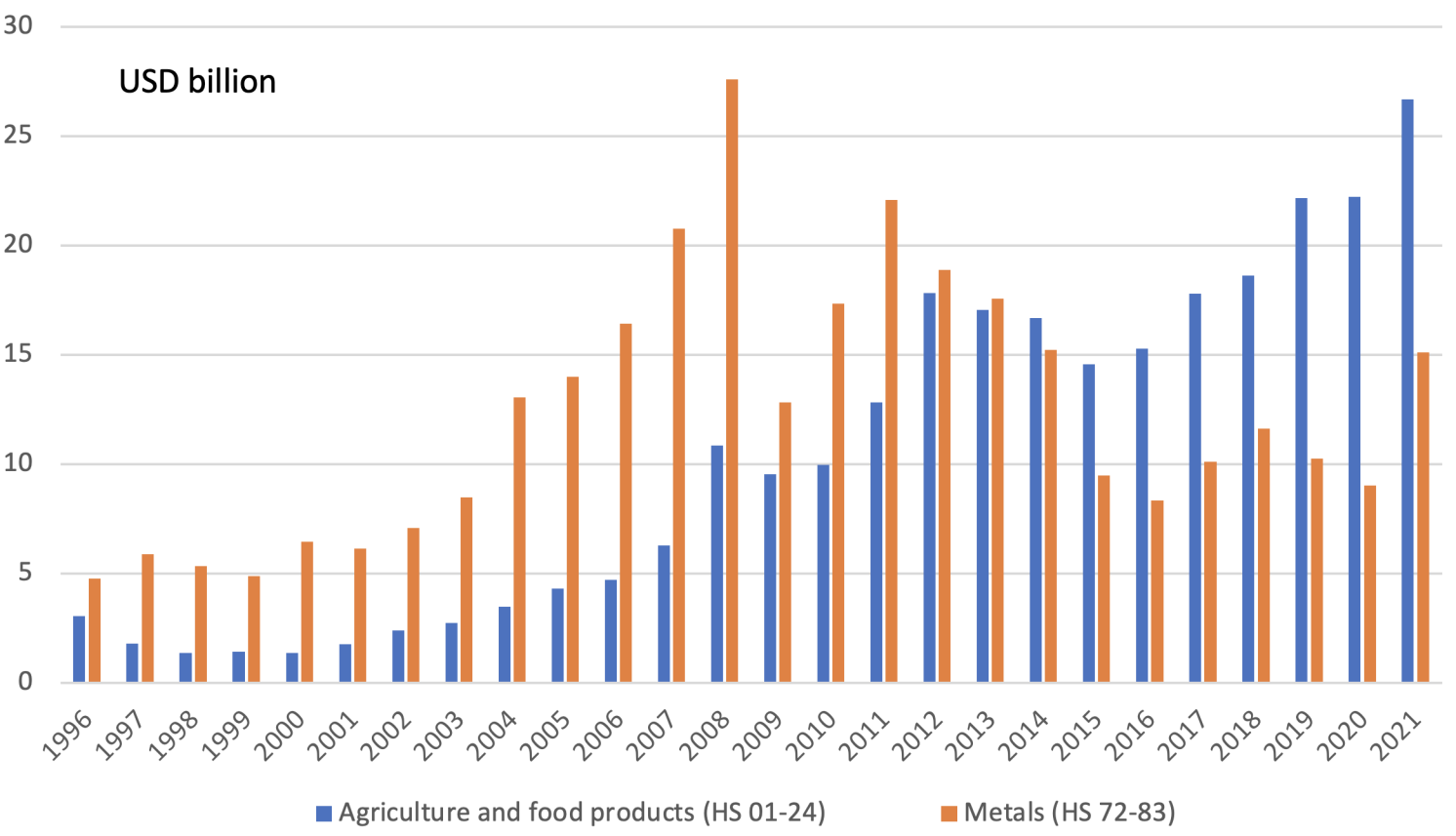

The good news is that trade was already a bright spot before the latest invasion, with Ukraine having achieved a high degree of openness and become an important exporter, particularly in agro-food products. In recent years, Ukraine has become the world’s second largest grain exporter after the US, and the dominant supplier of sunflower-seed oil. Notably, Ukraine has been shipping genetically modified organism (GMO)-free plants, including maize and soybeans, which are in high demand in the EU. Figure 1 below shows the stunning success of Ukraine’s agricultural exports pre-2022, as they overtook its former main export: metals.

Figure 1 Ukraine’s exports of agri-food products and metals (US$ in billions)

Source: Movchan and Rogoff (2022).

The country also has a fast-growing IT sector; Ukraine’s stunning success in containing Russian cyberattacks is testimony to its world-class programmers, who will be a powerful asset in a civilian economy. Technology exports have continued growing even in 2022, unfettered by transport difficulties and the blockade, and despite loss of some electricity generation capacity. Overall, Ukraine’s newfound status as an EU accession country opens vast possibilities for expanding trade.

Although the pre-2022 trade story was by and large a success, there are significant areas for improvement. The country’s participation in global value chains has remained limited. Ukraine is a supplier of raw materials (grains, iron ore) and intermediate goods such as sunflower-seed oil in bulk, various ferrous metals, ignition wiring sets and more, but its role in final production remains modest. This is a key area for improvement. In our paper (Movchan and Rogoff 2022), we discuss in detail the significant progress Ukraine has made in negotiating past trade agreements, as well as the agreements it is currently discussing; combined, they should help provide a framework for deeper integration into global value chains in some industries. Of course, here, too, much depends on rebuilding and improving Ukraine’s transportation links. Post-conflict Ukraine may also establish strong exports in some new areas, such as weapons production (where Ukraine will have built enormous credibility) and medical treatments (where Ukraine has developed innovative approaches to helping burn victims).

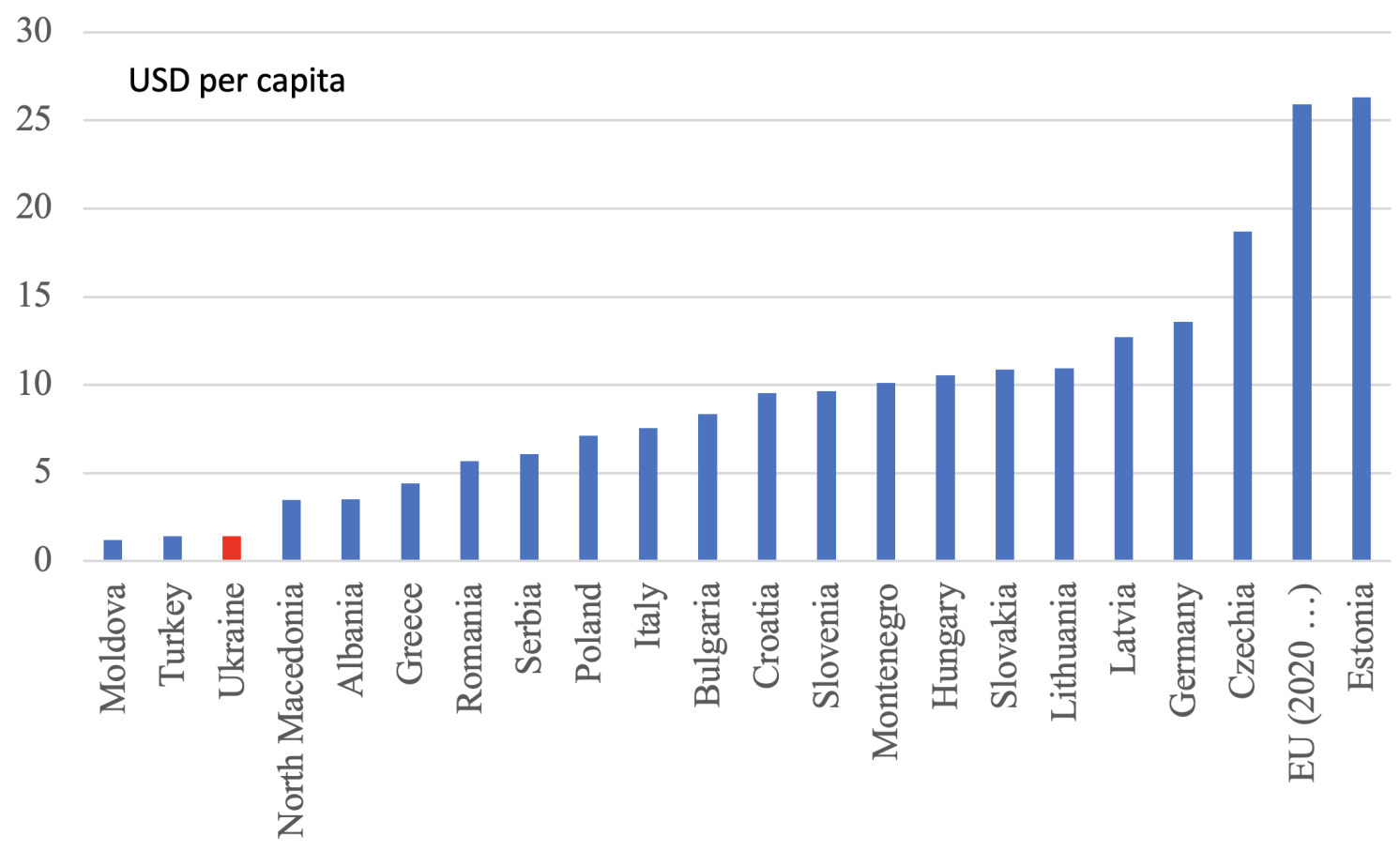

The situation with foreign direct investment (FDI) is much more difficult, but it will need to be solved for Ukraine to fulfil its trade potential. With Ukraine having suffered so much damage to its infrastructure, and with Russian drone and missile attacks laying waste to many factories and metal-processing plants, rebuilding is going to require a considerable investment of capital. Here, Ukraine’s weak past performance in attracting foreign direct investment provides less of a foundation, and it will be essential to strengthen institutions and legal systems to stem corruption and other problems that have hampered FDI into the Ukraine. An optimistic but fully plausible view is that Ukraine will benefit greatly from the process of integrating into the EU, which offers a template for reform. The experience of integrating former Eastern bloc countries into the EU has been varied; it will be important to benefit from this experience.

The challenge Ukraine faces is captured in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Foreign direct investment stock per capita, 2021 (US$ in thousands)

Source: UNCTAD, Movchan and Rogoff 2022.

Of course, Ukraine’s difficulties in attracting FDI pre-2022 already reflected the earlier Russian invasion of Crimea and Donbas. Nevertheless, even pre-2014, FDI was not strong.

What is the path going forward for both trade and FDI? Rogoff and Movchan (2022) give a broad overview of the past, present, and potential future. Given its candidate status, Ukraine should make use of European integration requirements to frame all of its policy changes, including those related to reconstruction (see also Emerson et al. 2021). The lure of EU membership can help navigate the reform process and mitigate related potential internal conflicts, as it has for previous accession countries. Ukraine can envision rebuilding that takes into account EU norms related to environmental protection, energy efficiency, and construction, conditions that will certainly be required to unlock EU aid funds should they materialise.

The discussion to this point has been quite abstract. Concretely, what steps can Ukrainian authorities undertake now to prepare for post-war trade integration?

Implementing current EU-Ukraine Association Agreement opportunities

This includes, for instance, the conclusion of the Agreement on Conformity Assessment and Acceptance (ACAA) of industrial products and the mutual recognition of equivalence for food products. The Association Agreement also envisions concluding special transport agreements that should allow the replacement of the temporary wartime agreement on road transport with a long-term deal opening access to the EU market for Ukrainian carriers. For telecommunications, postal, maritime, and financial services, achieving internal market treatment will be essential. Further opening of the public procurement market, in addition to the access provided through the WTO Government Procurement Agreement, will also be important.

- Joining recent EU sectoral initiatives. For instance, Ukraine is interested in joining the EU Digital Single Market and taking part in the EU Green Deal implementation.

- Concluding further free trade agreements (FTAs) with a focus on the EU’s trade partners, such as Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. These are countries in the Mediterranean region, and an FTA with them would allow better use of the Pan-European-Mediterranean Convention on preferential rules of origin (the PEM convention). Other potentially promising partners for FTAs are South Korea, India, and Indonesia.

- Completing fundamental reforms related to the rule of law and property rights protection. This is the major priority not only to attract foreign investment but to promote long-term growth generally.

- Introducing new risk-insurance schemes. In anticipation of post-war tensions – or, at a minimum, the tail risk of further tensions – a multi-donor fund to cover non-economic risks for foreign investors will be needed. There has been some experimentation with such donor funds at the World Bank, though the viability of this on the scale of Ukraine’s economy may be difficult to secure. For better trade financing, the Export Credit Agency capitalisation by international donors will help to boost exports.

- Further developing quality infrastructure. This includes rebuilding laboratories and other specialised facilities affected by the full-scale war, establishing new facilities, and improving Ukrainian public servants’ capacity in spheres related to quality control.

- Establishing better transport and logistic links between Ukraine and the EU for all transport means. For this, the development of intermodal transportation hubs in Ukraine is needed.

Successful implementation of these recommendations requires the ongoing commitment and active involvement of Ukraine and its partners. Given the ongoing transformation of Ukraine’s legislative practices and institutions in preparation for EU membership, the EU’s role in implementing these recommendations is essential. This will involve not only financial and technical support but also the readiness to swiftly integrate Ukraine into sectors and spheres envisaged by the Association Agreement and sectoral deals that are already in place prior to full membership.

Lastly, we must emphasise that our discussion on possible paths for trade and FDI pertains to a post-conflict world. Until then, the wartime economy requires a more restrictive approach, such as the use of capital controls. But long-term, the potential transformation offered by EU membership – a transformation that will come largely from within – is the best hope for the future. It is time to start planning and acting.

This article was first published by CEPR.

References

- Emerson M, V Movchan, T Akhvlediani, S Blockmans and G Van der Loo (2021), Deepening EU-Ukrainian relations: Updating and upgrading in the shadow of COVID-19, CEPS and IER.

- Gorodnichenko, Y, I Sologoub and B Weder di Mauro (2022), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, CEPR Press.

- Movchan, V and K Rogoff (2022), “International Trade and Foreign Direct Investment”, in Y Gorodnichenko, I Sologoub and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principle and Policies, CEPR Press, 119–165.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations