Since February 24th 2022 the full-scale Russian invasion has completely grabbed the attention of Ukrainians and moved other topics to the periphery of the information sphere. Since the news from the frontlines are the most important, reforms are often out of the focus of public attention, although there is no doubt that despite martial law the reforms should continue. Continuing reforms is important not only to show to the Western allies Ukraine’s dedication to the EU integration but first of all to modernize the Ukrainian state and to make it more resilient. To be sustainable, reforms should be supported by people. Therefore, we asked Ukrainians about their attitude to reforms.

The main results

- Ukrainians express high support for reforms, with relatively higher support of those reforms, results of which they can feel “with their own skin” (e.g., healthcare, education reform or digitalization). Understandably, Ukrainians name the army reform as one of the most important (although it may not be rational to radically reform the army during the full-scale war).

- Perceived importance of judicial reform, development of public procurement or privatization is lower, although these reforms are crucial for modernization of the country. Thus, there is a need for more intense communication of the importance and impact of reforms in those spheres which citizens rarely face in their everyday life.

- The most expected reform result is lower corruption, with increased welfare in the second place.

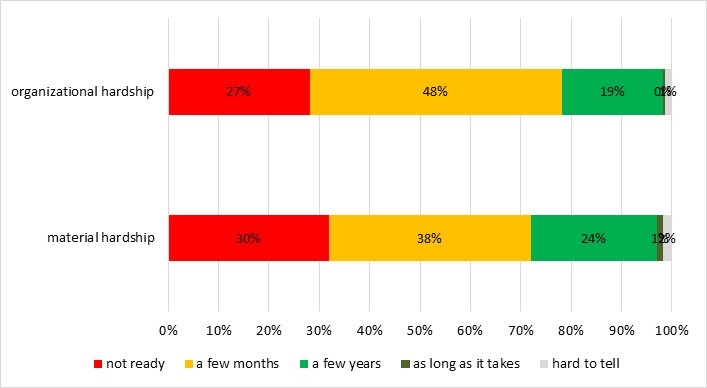

- About a third of Ukrainians (primarily from lower-income households) are not ready to withstand temporary hardships while reforms are being implemented, and 30-40% can cope for just a few months. People participating in civic activity are more likely to support reforms and more patient about their results.

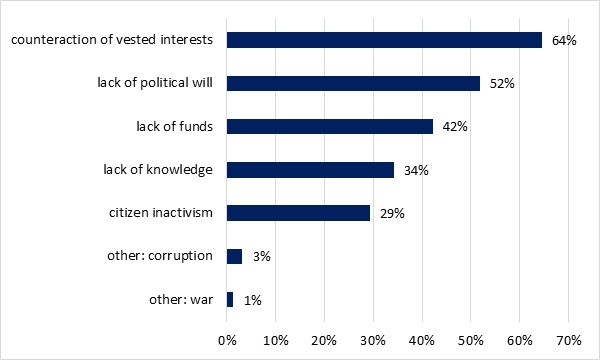

- The main obstacles to reforms in the eyes of Ukrainians are counteraction of vested interests and unwillingness of the government to implement them rather than lack of money or knowledge.

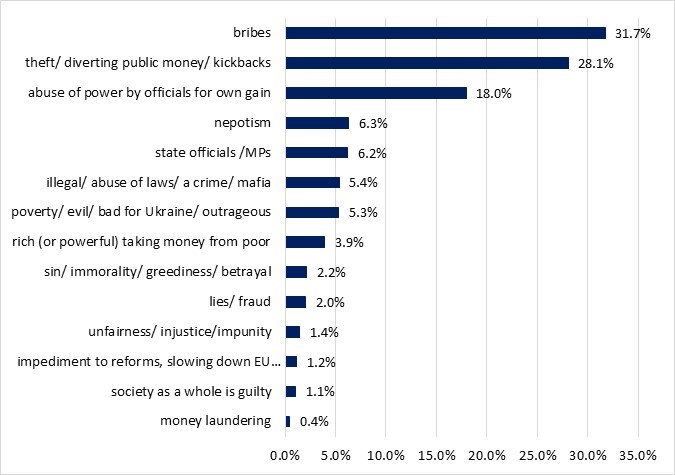

- Ukrainians associate corruption mostly with bribes, diversion of public funds and abuse of power by officials.

- Since the start of the full-scale war civic activity refocused towards volunteering and charity. After the war ends, civic activity, especially charity, will decline, and there will be a rotation of people – some will leave the NGO sector while others will join. Taking into account the significant role of civil society in the after-war reconstruction, this sector will require some support.

- Our policy recommendation to the government is to involve citizens into the reconstruction and reform process. This will increase citizens’ understanding of reforms and therefore popular support and sustainability of reforms. This will also increase popular trust in the government.

Data description

The survey had three sets of questions: on reforms (importance of reforms, expected result and impediments to reforms), on corruption, and on civic activism. Besides, a number of personal variables were recorded – sex and age, household size, education, employment (both whether a person is employed, unemployed or out of labour force and a more refined set of questions on a person’s main economic activity); self-defined material stance (from “we do not have money even for food” to “we can buy everything we want”), region and type of settlement (urban/rural) where a respondent lived before the full-scale war. The share of refugees in the sample is 5%. The majority of people did not answer questions about their current location, thus we did not include this information into our analysis.

The survey was implemented by Info Sapiens polling company during 12-30 October 2022; method: online interview, sample: 2113 respondents 18+ who lived in government-controlled areas as of February 23rd, including those who moved abroad after February 24th; the sample is representative for Ukraine’s population by sex, age, settlement size and region according to Ukrstat data as of 01.01.22, theoretical error is no more than 2.2% for total sample. The survey data can be found here.

“Personal” reforms are perceived as more important

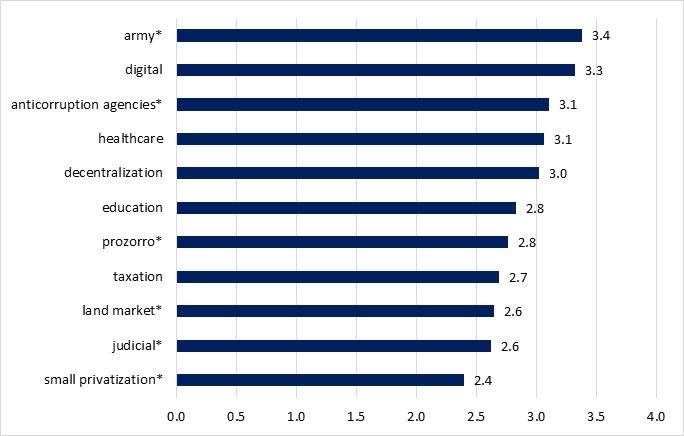

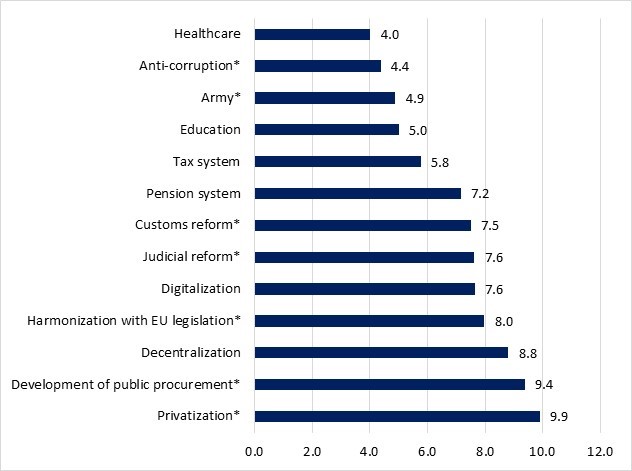

Prioritization of reforms differed depending on question formulation. Figure 1 compares the relative importance of reforms when people were asked to evaluate their importance (panel A) and when respondents were asked to rank the reforms. In each panel stars mark “general” reforms, i.e. those the effect of which a person usually would not feel directly, while non-starred are more “tangible” reforms, i.e. those which a person is more likely to feel in her everyday life. In both rankings “general” reforms have slightly lower scores than “personal” reforms, which suggests that people perceive reforms that have a direct impact on their lives as more important.

Figure 1. Relative importance of reforms

Panel A. Answers to the question: How important are the following reforms (very important, rather important, rather not important or not important. Respondents could have also selected the answer “I have never heard of it”). Respondents were provided with a brief description of each reform.

Note: numbers represent weighted average scores of each reform where 4= very important, 1 = not at all important and 0 = have never heard of it. Higher scores represent more important reforms. Average score of “general” reforms is 2.8 compared to 3 for “personal” reforms.

Panel B. Ranks of reforms: respondents were asked to rank each reform from 1 to 13 (1 = the most important)

Note: here lower scores represent more important reforms. Although the list of reforms slightly differs from panel A, again “general” reforms are slightly less important (average score 7) compared to “personal” reforms (average score 6.8).

Both panels of figure 1 show that the most important for Ukrainians are reforms of the army, healthcare, and anti-corruption. This is reflected in the expected results of reforms (see Figure 4 below) with lower corruption being the most expected. Interestingly, judicial reform and privatization which are key elements in lowering corruption are not prioritized. Thus, there is a need for more communication on how these reforms can lead to lower corruption and how they impact the lives of people.

Importance or reforming the army in the eyes of Ukrainians grew in 2022 after the full-scale Russian invasion. Thus, according to the survey of Democratic Initiatives Foundation, in 2020 the most important reforms for Ukrainians were anti-corruption, healthcare and pension. Army reform was in the middle of the list, and education, land and energy reform were the least important.

Previous surveys show that people’s awareness can impact popular support of so-called “social” reforms. Thus, Razumkov Centre 2018 survey shows that respondents who were more aware about certain reforms more often noticed their positive impact, whereas lower awareness raised the share of respondents who did not feel the impact of reforms or felt negative impact. Healthcare reform is an exception: this same survey shows that Ukrainians were most aware about it but more than half of respondents (57%) evaluated its impact as negative.

Digitalization became a flagship reform of the Zelensky government, and since the start of the full-scale war access to administrative services and their convenience became even more important: during six months since February 24th the number of IDPs in Ukraine increased to almost 7 million people (from 1.5 million before the full-scale invasion). These people needed respective documents, payments and support. Administrative service centers were not able to quickly do the paperwork, and the lines sometimes could last for several weeks. Partially this problem was solved via Diia app. In April the Ministry of digital transformation introduced an opportunity to get an IDP certificate and support from the state. As of December 13 almost 1.5 million citizens have used this service.

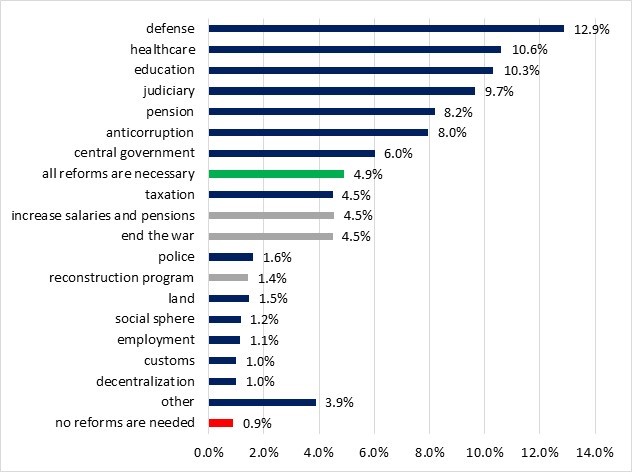

Figure 2 presents answers to the open question “Which reforms are needed in 2023?” The answers to this question should be rather interpreted as the spheres about which people care most in the short run because we have quite a few answers “to increase salaries and pensions” or “to lower prices” which are not reforms but are often expected from the government. In this list of priorities the judicial reform is rather high – right after the defense, healthcare and education.

Figure 2. What reforms are needed in 2023? (open question, share of respondents, %)

Note: in this figure answers that are not reforms but rather people’s wishes are marked with gray.

As we see from figures 1 and 2, generally reforms are quite important for Ukrainians. What defines whether a person considers certain reforms important? Our estimation* shows out that men care less than women about education, healthcare and anticorruption reforms but care more about judiciary reform and state-level reforms in general**. Perhaps women more often take care of education and healthcare for the family and consequently deal with petty corruption and other problems in these spheres. People aged 45+ are more likely than youth 18-25 to consider taxation, decentralization and public procurement reforms as important, while youth 18-25 expectedly are more likely to mark education reform as important. People with higher or incomplete higher education are more likely to care about taxation, introduction of anti-corruption agencies, digitalization and army reforms.

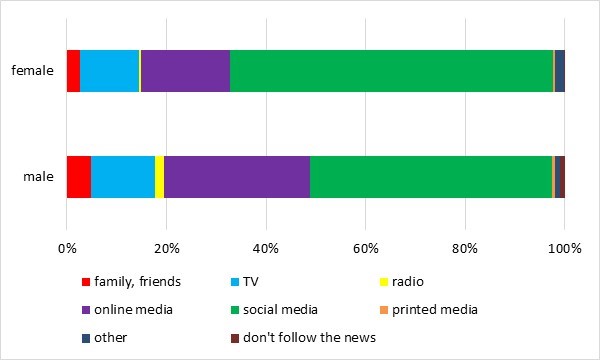

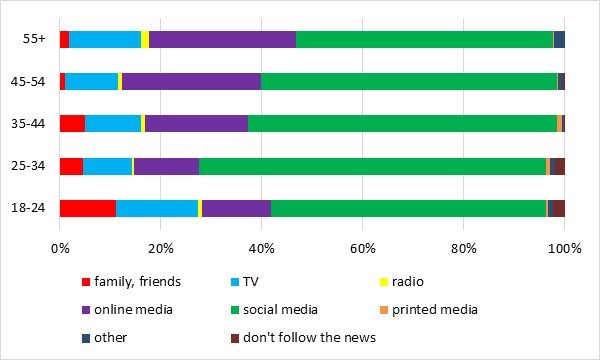

Poorer people (those saying that they do not have enough money even for food) are expectedly less likely to care about reforms. City dwellers are more likely to care about such reforms as digitalization, anti-corruption agencies, introduction of Prozorro, and decentralization. People who derive news mostly from online media and social media are more likely to support “general” reforms such as judiciary, army reform, small privatization, creation of anti-corruption agencies, but also decentralization and healthcare reforms. However, since these are primary news sources for Ukrainians (see Figure 3), we should be cautious about this result – it can be simply that people who follow the news (from any media source) are more likely to support reforms. Finally, civil activists are more likely to support reforms.

Figure 3. Distribution of respondents by their main news source, %

Panel A. By gender

Panel B. By age intervals

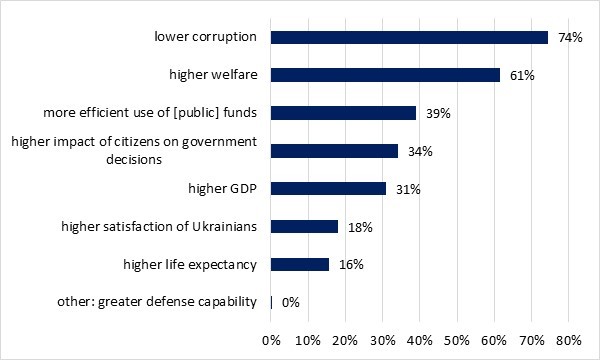

Lower corruption is the most important expectation from reforms

Since corruption has been high on the agenda of Ukrainian society for more than a decade, it is natural to see that Ukrainians expect from reforms first of all reduction of corruption (almost ¾ of the sample). Over 60% expect higher welfare, while other answers are less frequent (Figure 4, panel A). Males are more likely to name GDP increase as an expected reform result and less likely to name welfare, which is consistent with their slightly higher probability to consider “general” reforms as important. Civil activists are also more likely to expect GDP increase and less likely – welfare and life expectancy increase. People with higher education are more likely to expect lower corruption, higher welfare and life expectancy and less likely – higher citizen impact as a result of reforms.

Not unexpectedly, richer people are more willing to withstand some hardship during implementation of reforms, as are civil activists. The first category may have a longer planning horizon, while the second one can be more aware that reforms do not have an immediate effect (Figure 4, panel B).

Figure 4. People’s expectations of reforms and how long they can withstand temporary hardship

Panel A. Expected reform results (a respondent could select no more than 3 answers)

Panel B. For how long are you willing to withstand temporary hardship during implementation of reforms?

Counteraction of vested interests and lack of political will are the main obstacles to reforms

What do citizens see as impediments to reforms? These quite naturally stem from the perception of corruption as one of the main Ukrainian problems. Thus, two main barriers to reforms in view of Ukrainians are counteraction of vested interests and lack of political will (figure 5).

Taking a closer look, we can suggest that respondents’ answers depend on their personal experience. Thus, people with higher education are more likely to name citizen inactivity and less likely lack of money as an impediment to reforms. People from richer households, employees of private companies or self-employed are more likely to blame vested interests, while non-working people – citizen inactivity. Those working in NGOs or studying are more likely to blame lack of knowledge, while public employees – lack of both knowledge and money. Civic activists are more likely to name vested interests, lack of knowledge and citizen inactivity as impediments to reforms and less likely – lack of political will or money.

Figure 5. What are the main obstacles to reforms? A respondent could name no more than three options and provide his/her own version

Corruption is mostly associated with bribes and diversion of public funds

The next block of questions concerns corruption. Here respondents were asked to define corruption (an open question) and to define whether some situations can be considered as cases of corruption, not corruption or depending on the circumstances. Based on the answers to the second question, we calculated the corruption score*** for each respondent (the higher the score, the more correct answers a respondent provided). Expectedly those with higher corruption scores were more likely to consider anti-corruption and related reforms (judicial, privatization, taxation, public procurement) as important. They were also more likely to expect less corruption and higher GDP as a result of reforms and more likely to blame vested interests and lack of political will for slow reforms.

The definition of corruption provided by respondents is quite interesting. We classified the answers into several categories (Figure 6). These categories can be interpreted as things with which respondents associate corruption. Expectedly, bribes, misuse of public funds and abuse of power were the most frequent answers. Many more Ukrainians (6.2%) associate corruption with the government (in a broad sense) than with society as a whole (1.1%). About 4% directly stated that corruption implies “rich” or “powerful” extracting money from “ordinary citizens”. This suggests that more communication on integrity and proper governance practices is needed, as well as on how citizens can enforce those practices.

Figure 6. Respondents’ definition of corruption, open question (a respondent could provide several answers)

Note: answers were manually classified into these categories. Category “abuse of power by officials” may contain some fraudulent answers since some respondents obviously just copy-pasted the definition of corruption from Wikipedia. We tried to exclude such answers but cannot guarantee 100% success since we’ve given our respondents the benefit of the doubt.

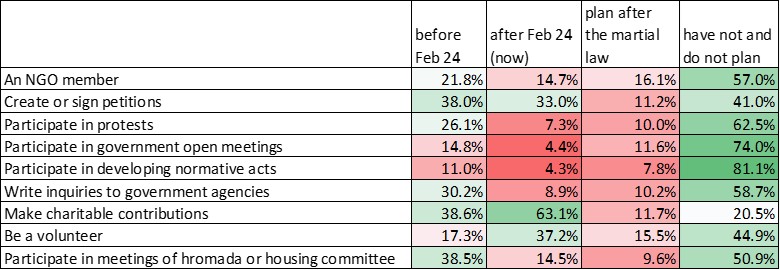

Today civic activity is concentrated in volunteering and donations; a new wave of activists will emerge after the war

Finally, we asked our respondents about their civic participation. Table 1 presents the shares of people who participated in certain activities before February 24th 2022, after this date (i.e. they are participating in these activities now), plan to do this after the war or never participated and do not plan. Table 1 shows that the least “popular” activities are participation in writing normative acts or in government meetings, whereas many people wrote or signed petitions or donated money – probably because this is the least time consuming. We also see an understandable drop in protest activity and an increase in volunteering and donations after February 24th. After the war many people plan to scale down their civic participation.

Table 1. Civic participation of respondents (% of those who answered yes to a certain type of activity)

Note: neither rows nor columns add up to 100 since a person could participate in a few activities simultaneously as well as participate (or plan to participate) in them during several time periods.

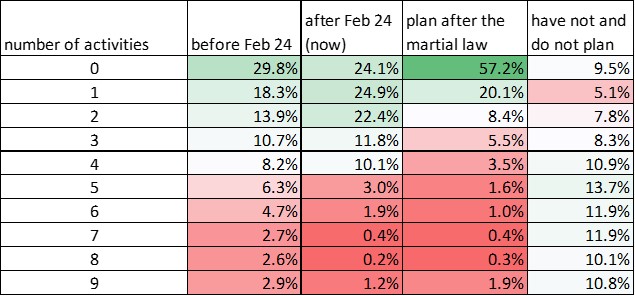

Table 2 shows that decent shares of people are involved in several related activities simultaneously, e.g. write petitions and participate in government meetings or participate in NGOs and in development of normative acts etc. Those who are currently volunteers are more likely to also be NGO members and provide charitable contributions. In the current time we see more concentration of activities compared to the period before February 24th: today only about 7% of respondents take part in 5 or more activities while previously this share exceeded 19%.

Table 2. In how many civic activities respondents participate(d)

Note: the share of people who have not and do not plan to participate in any of the activities is in the bottom right corner of the table (10.8%). Columns of this table add to 100%.

We have not identified personal characteristics that unequivocally increase a person’s civic activism (younger females may have a higher probability of involvement but the result is not robust). Perhaps, a person’s participation in a civic activity is due to some unobserved factors.

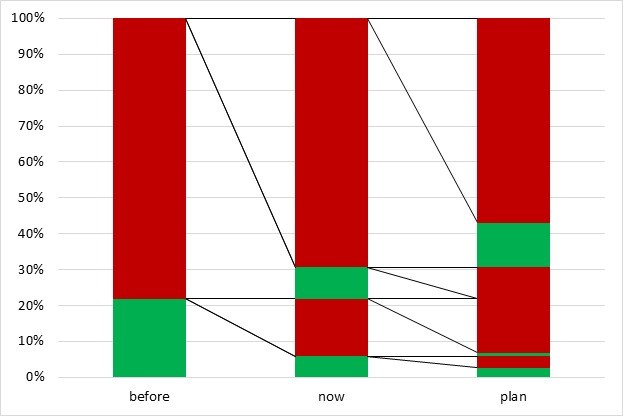

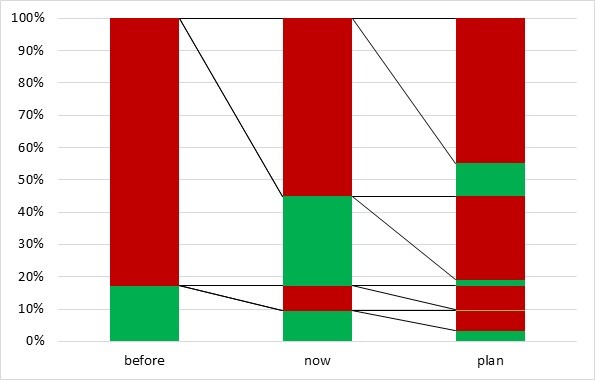

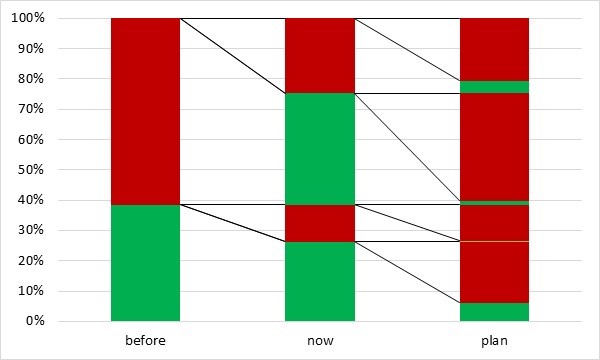

We have also looked at how persistent civic participation is and how many people switch from activity to inactivity and vice versa. We looked at three types of civic activity (figure 7) – being an NGO member (panel A), being a volunteer (panel B), making charitable contributions (panel C). Figure 7 suggests that there are and there will be significant inflows and outflows into and from civic activities. Thus, only 2.7% of people were in NGOs before February 24th, are in an NGO now and plan to continue being an NGO member after Ukraine’s victory. 68% of those who were NGO members before February 24th (15% of respondents) seem to have exited the NGO sector for good (although their plans may change in the future). On the other hand, 19% of those who have never been an NGO member (and 12% of respondents) plan to join an NGO after the war.

Likewise, 3.3% of respondents were volunteers before February 24th, are volunteers now and plan to continue this activity in the future. 26% of respondents (and 70% of those who are currently volunteers) became volunteers after February 24th and do not plan to continue this activity after the war. Generally, volunteer activity after the war will return to approximately its pre-war level, although different people will be involved in it. To the contrast, charitable activity, although considerably increased after February 24th (from 39% to 63%) will largely decline after the war – only 11% plan to be involved in it after the war. More than a half of them will be those people who made charitable contributions before the full-scale war and continue to donate now (6.1% of total number of respondents). About a third of people who made contributions before February 24th stopped donating after the full-scale invasion, while 61% of those who did not donate started donating after February 24th. After the war people will need money to restore their health, houses etc. – and this can explain an expected decline in charitable activity.

Figure 7. Movement of people from and to civil activism

Panel A. Participation in NGOs

Panel B. Being a volunteer

Panel C. Making charitable contributions

Note: to see the share of respondents who were, are now or plan to participate in a certain activity, add up green parts of respective columns.

Concluding remarks

The survey showed that not all Ukrainians can clearly define what a reform is, but the majority of them believe that reforms are important. Higher importance of reforms which one can feel “with her own skin” suggests that more explanation of “general” reforms is needed. Specifically, today the most important reform is the “reload” of the judiciary.

Today civil activism – namely, the share of people who are volunteers or those who donate – increased, but after the war civic participation will be lower. Moreover, there will be some rotation of people – some civic activists will exit to other sectors while others will join.

We recommend the government to involve civil society into all stages of the reconstruction process – project development, prioritization, implementation, and evaluation (audit). This will not only attract more people to the sector but also increase the trust in the government as well as popular support for reforms, which is necessary for their sustainability.

* Probit regression with dependent variable equal to 1 if certain reform is important or rather important for a person. Independent variables are demographic characteristics, civil activism and news sources. Estimation results are available from the authors upon request.

** Here and in further in this text only statistically significant results are reported.

*** Correct answers were considered as +1, incorrect as -1, the sum was divided by maximum possible score.

This publication was produced within the framework of the “Support of think tanks” project which is carried out by the International Renaissance Foundation with the financial support of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine and the International Renaissance Foundation.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations