In November, President Joe Biden’s administration warned Congress that the United States is “out of money and nearly out of time” to send aid and weapons to Ukraine. This, together with the recent warning by Ukraine’s top general, Valery Zaluzhnyi, that “sooner or later we are going to find that we simply don’t have enough people to fight,” has been interpreted by some commentators as a sign of Ukraine’s imminent defeat and the urgent need to negotiate with Russia.

But this interpretation echoes the calls to abandon the United Kingdom during World War II and, more recently, the futile “non-escalation” approach embraced by the West since Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008.

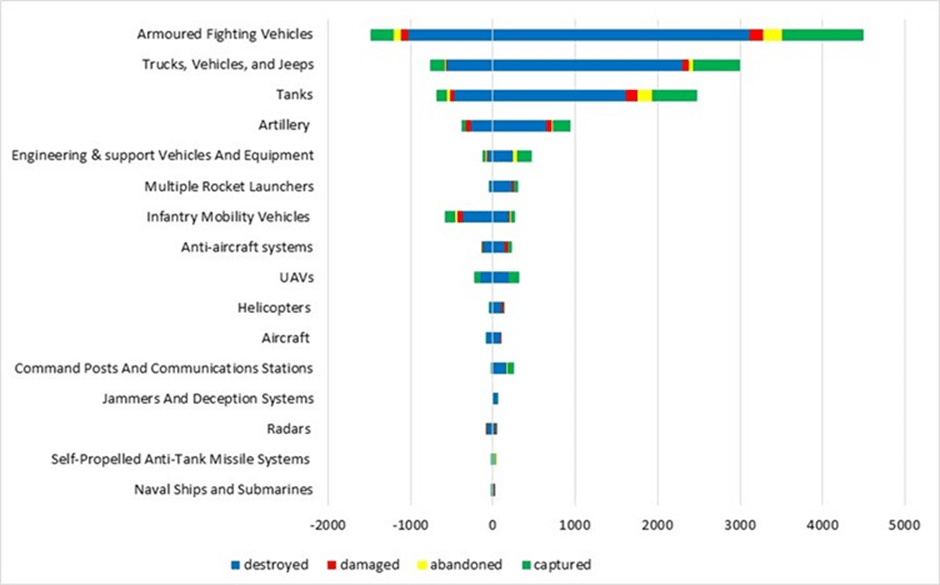

The data tell a different story. Table 1 outlines what Ukraine has been able to achieve with the resources at its disposal. Although these figures are based on open sources like Oryx and are probably imprecise, each data point is supported by photographic and video evidence. Even with this incomplete dataset, Figure 2 clearly shows that the Ukrainian army has been significantly more effective in neutralizing Russian equipment than Russia has been in destroying Ukrainian weapons and supplies. Moreover, Ukraine has managed to retake roughly half of the territory that was under Russian control in the summer of 2022.

Table 1: Comparison of the Ukrainian and Russian Armies Before February 2022 and the End of November 2023

| Early 2022 | Captured during the war by | Lost during the war by | Received from abroad | ||||

| Russia | Ukraine | Russia | Ukraine | Russia | Ukraine | Ukraine | |

| Aircraft* | > 1,390 | 128 | 1 | -94 | -77 | 45 | |

| Helicopters* | > 948 | > 55 | 3 | 2 | -130 | -33 | 68 |

| Air defense | > 2,234 | > 400 | 13 | 46 | -180 | -127 | 681 |

| Tanks* | 3,417 | 987 | 134 | 548 | -1930 | -555 | 759 |

| Various armored fighting vehicles | > 20,310 | > 3,730 | 411 | 1041 | -3728 | -1655 | 6598 |

| Artillery | > 5,500 | > 1,960 | 41 | 207 | -730 | -333 | 944 |

| Surface-to-surface missile launchers | > 150 | 90 | 8 | 53 | -255 | -42 | 105 |

| Warships | 203 | 14 | 17 | 0 | –18 | -10 | 135** |

| Submarines | 49 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 |

| Unmanned combat aerial vehicles | n/d | n/d | 0 | 3 | -11 | -25 | 35 |

| Reconnaissance UAV | n/d | n/d | 74 | 132 | -179 | -125 | 1349 |

| Supporting vehicles | n/d | n/d | 183 | 575 | -2427 | -580 | 153 |

| Engineering vehicles and equipment | n/d | n/d | 26 | 125 | -238 | -73 | 295 |

| Radars | n/d | n/d | 11 | 10 | -73 | -36 | 113 |

| Jammers and deception systems | n/d | n/d | 1 | 7 | -56 | -3 | – |

| Command posts and communications stations | n/d | n/d | 4 | 84 | -174 | -14 | – |

Sources: Defense News, Statista, and Oryx reports on Ukraine and Russia (retrieved at the end of November 2023).

*In other sources, the total number of planes and helicopters was estimated to be more than 4,000, and the number of tanks was estimated at 12,950; General Zaluzhnyi stated that only 40 Ukrainian airplanes and helicopters could fly in early 2022. **Unmanned vessels. Negative numbers indicate equipment loss due to damage or destruction.

Figure 1: Ukrainian (left) and Russian (right) equipment losses Since February 2022

Source: Oryx data

But Russian President Vladimir Putin has access to a nearly limitless supply of cannon fodder. And although Russia’s logistical infrastructure is vulnerable (even in Siberia), its weapons factories, located far from the frontlines, remain largely intact. Delays in Western weapons supplies to Ukraine have enabled Russia to build robust defense systems in the occupied Ukrainian territories, impeding Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive.

Moreover, Russia is ramping up weapons production. Its military budget for 2024 is projected to be at least $120 billion, compared to $76-77 billion in 2022-2023 and $48 billion in 2021. And these estimates do not include additional defense spending funneled through the police and security services, as well as “private military companies” like the Wagner Group. Russia is also rapidly adjusting to modern warfare: according to some estimates, it has the capacity to deploy 20,000-25,000 first-person view (FPV) drones to the frontline per month.

So, is it time to reduce aid to Ukraine and initiate negotiations with Russia? The fact that Putin has violated numerous treaties would cast substantial doubt on the credibility of any deal. But to determine whether lasting peace is feasible, it is crucial to consider Russia’s strategic objectives.

First, Russia has not pursued negotiations with Ukraine; it is demanding total capitulation. Such a “peace deal” would result in Ukraine’s annihilation and the implementation of Russia’s original plans for mass terror and famine, reminiscent of the Soviet Union’s atrocities of the 1920s and the mass starvation of millions of Ukrainians during the Holodomor in the early 1930s. The horrifying massacres in Bucha and numerous other Ukrainian towns and villages, along with the tens of thousands of Ukrainian children that have reportedly been abducted by Russia, illustrate the unimaginable cruelty of the Russian “liberators.”

Second, the Ukraine war is only the first phase of a broader conflict between Western democracies and a new “axis of evil” comprising Russia and its allies. As Christian Mölling and Torben Schütz recently put it, the question facing NATO and Germany is not if the conflict will escalate into an all-out war, but when. Their analysis suggests that following the cessation of hostilities in Ukraine, Russia would require 6-10 years to build the military capabilities necessary to mount a conventional attack against NATO.

But Russia’s hybrid assault on NATO countries is already well underway. Over the past few years, Russia has attempted to undermine liberal democracies by spreading disinformation and supporting far-left and far-right populist parties in throughout the West. It is also enabling terrorism: following Hamas’s October 7 massacre of more than 1,200 Israelis, the group’s leaders received a warm welcome at the Kremlin. Russia’s strategy relies on democracies becoming increasingly polarized, growing weary of the war in Ukraine, and electing populist or pro-Russian governments that would further weaken their institutions.

Liberal democracies must confront this harsh reality. Putin has made no secret of his imperial ambitions, and peace negotiations will not halt his aggression. Just as Adolf Hitler’s quest for power did not end with the Munich Agreement, Putin’s war against the West will not end with the massacres in Bucha and Israel. If Western leaders want to prevent similar atrocities within their own borders, they must support Ukraine until Russia is defeated.

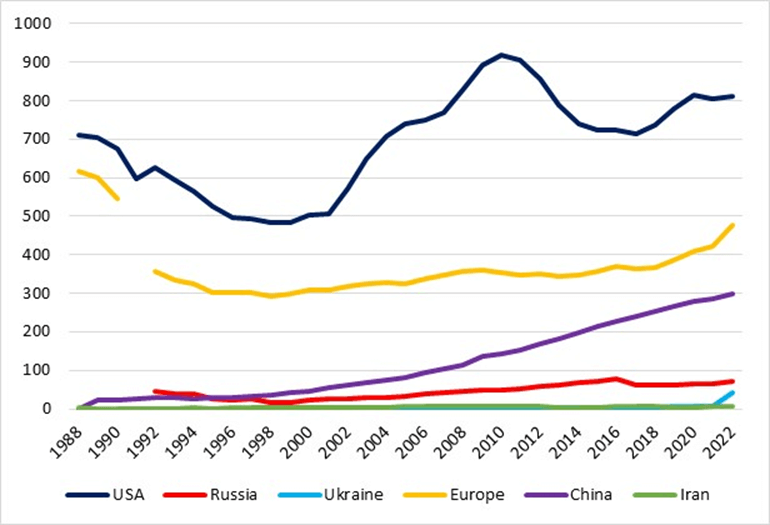

As Zaluzhnyi has noted, Ukraine requires more resources and advanced weapons to counter Russia’s war of attrition. Given that the West’s economic power easily surpasses Russia’s, that is not a daunting task. While Russia has spent tens of billions of dollars building its war machine, these sums are dwarfed by the combined defense budgets of the US and Europe (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Defense Spending in Selected Countries (billions of constant 2021 US dollars)

Source: SIPRI database

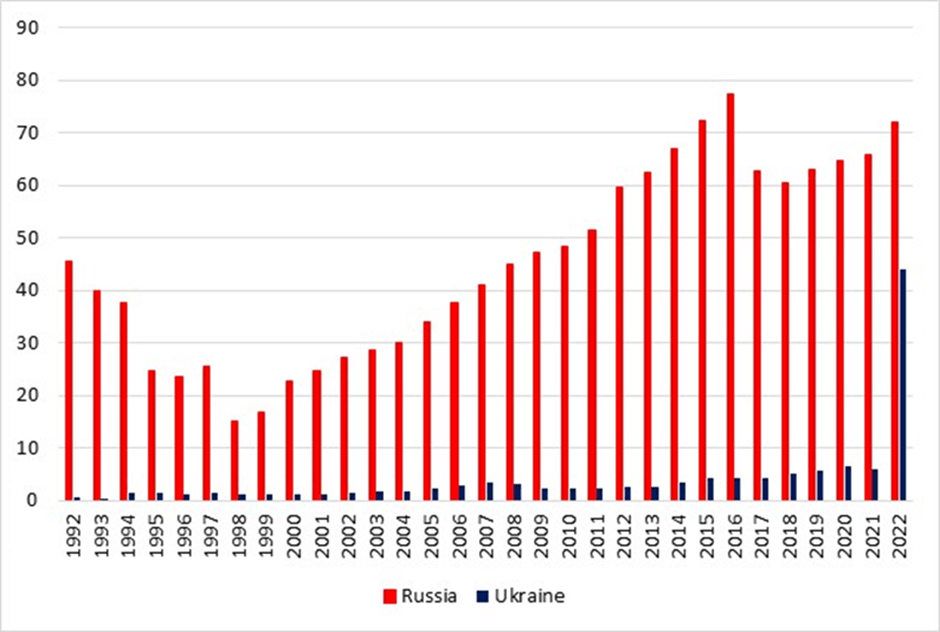

After receiving relatively modest aid from the West, Ukraine’s military capabilities still lag behind those of Russia, but the disparities are not as stark as they were before 2022 (Figure 3). Moreover, Western countries could leverage Russia’s dependence on technologies, goods, and revenues from the rest of the world. To disrupt the Russian war machine, these channels must be cut off.

Figure 3: Defense Spending in Ukraine and Russia (billions of constant 2021 US dollars)

Source: SIPRI database

While Russia and its allies may appear intimidating, they are economically, militarily, and technologically weaker than the world’s liberal democracies. But Western countries must not squander their significant advantage. Political infighting in the West empowers Russia and its allies and enables them to provoke more conflicts, further straining Western democracies’ military, financial, and emotional resources.

Russian revanchism can and must be defeated in Ukraine. Zaluzhnyi’s point was that to achieve that outcome, the era of piecemeal support must end.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2023

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations