Have Ukrainian researchers truly severed ties with their Russian colleagues? In the Scopus database, one can find hundreds of “joint” publications. In reality, their actual number is far smaller. Yet, the problem, at least for now, persists. This article examines how such data should be interpreted and what measures can be taken to reduce both genuine and fake instances of collaboration.

As of mid-2025, it is difficult to imagine Ukrainians cooperating with Russians in any sphere. The reason is not only in the very real risk of facing prosecution for treason, but also ethical considerations: after all the devastation Russia has inflicted on Ukraine, collaboration with Russian scholars is a stark contradiction to every moral principle.

In case of “flexible principles”, the Government of Ukraine has adopted a series of regulatory acts prohibiting scientific collaboration with representatives of the aggressor state, including:

- Law “On the Termination of the Agreement between the Government of Ukraine and the Government of the Russian Federation on Scientific and Technical Cooperation” (June 19, 2022);

- Resolution of the Presidium of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine No. 22 of January 24, 2024, “On the Unacceptability of Participation in Publishing Activities with Scholars Affiliated with Institutions of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus”;

- Letter of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine No. 1/2017-24 of February 6, 2024, “On the Need to Terminate Any Forms of Scientific (Scientific-Technical) Cooperation with the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus”;

- Order of the Presidium of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine No. 145 of March 7, 2022, “On the Termination of Cooperation with Scholars of the Russian Federation in the Publishing Sphere”;

- Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine No. 355 of March 24, 2022, “On the Denunciation of Agreements in the Field of Education and Science with the Russian Federation”.

These documents do not impose sanctions for collaboration with Russian scholars. However, they establish a legal basis for ending such cooperation and provide a framework for possible disciplinary measures within universities and research institutions.

Thus, it would be logical to assume that after 2022, Ukraine and Russia have not engaged in scientific collaboration. However, the facts contradict this seemingly reasonable assumption. As of mid-2025, about 90 Ukrainian scholars were still serving on the editorial boards of Russian journals, and the number of joint publications (that is, papers co-authored by Ukrainians and Russians) since the start of the full-scale invasion had exceeded 1,800 (according to Scopus data as of August 14, 2025).

Do these staggering figures represent an illusion or a troubling reality? Let’s find out.

Disclaimer: This research was conducted by the Working Group on Countering Russian Propaganda and Ending Cooperation between International Organizations and the Russian Academic Community, established by order of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

Based on Scopus data and the built-in SciVal analytics tool, it is clear that the number of joint publications has declined significantly since 2022 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Number of joint Russian–Ukrainian publications, 2014–2025 (according to Scopus data)

Let’s assess the scale of joint publishing activity after the start of the full-scale invasion. From early 2022 to August 14, 2025, the total number of publications was 1,806—comparable to the number for 2020 alone, when 1,513 publications were indexed. In other words, over three and a half years, there were roughly as many joint publications as in a single year before the full-scale invasion.

The overall trend is clear: a sharp decline in joint scientific activity. In 2022, the number of such publications fell by 38% compared to 2021; in 2023, by 49% compared to 2022; and in 2024, by 28% compared to 2023. Thus, in 2024, there was nearly 80% fewer joint publications than in 2020.

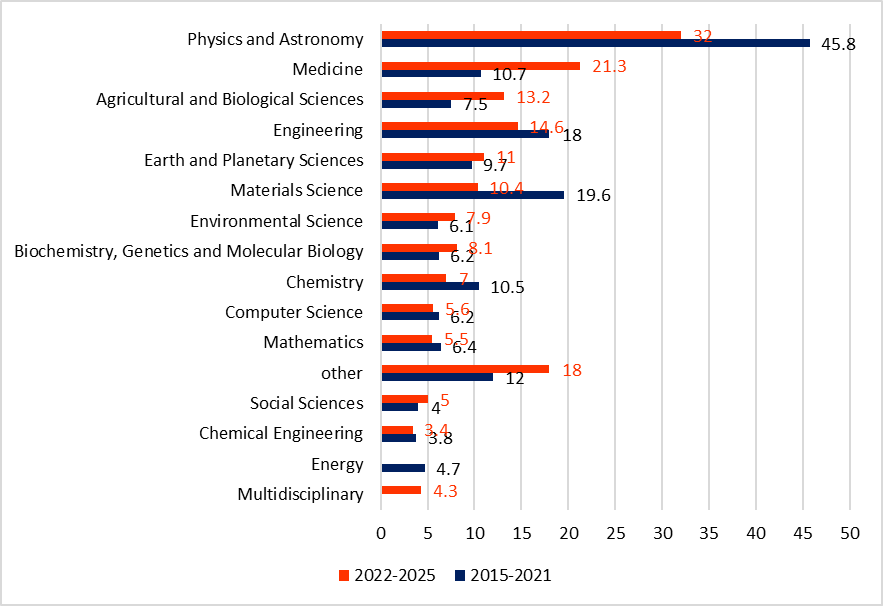

Figure 2. Structure of collaboration by scientific field before the full-scale invasion (2015–2021) and after it (2022–2025)

Source: compiled by the author based on Scopus data

After the start of the full-scale invasion, the distribution of joint publications by field changed significantly (see Figure 2). Physics and astronomy remained in first place, but their share fell from 46% to 32%. Medicine rose from fourth to second place, with its share increasing from 11% to 21%. Engineering, with a share of about 15%, stayed in third place, while materials science dropped from second to sixth, with its share nearly halving to 10%.

The list of the most active organizations in joint Ukrainian–Russian publications is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Most active organizations in joint Ukrainian–Russian publications, 2022–2025

| № | Institution name | Country | Number of publications |

| 1 | Russian Academy of Sciences | Russia | 886 |

| 2 | National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | Ukraine | 432 |

| 3 | CNRS | France | 314 |

| 4 | Lomonosov Moscow State University | Russia | 281 |

| 5 | Université Paris-Saclay | France | 233 |

| 6 | National Institute for Nuclear Physics | Italy | 217 |

| 7 | Russian Research Centre Kurchatov Institute | Russia | 213 |

| 8 | Université Paris Cité | France | 206 |

| 9 | Joint Institute for Nuclear Research | Russia | 203 |

| 10 | Imperial College London | UK | 200 |

| 11 | United States Department of Energy | US | 199 |

| … | … | … | |

| … | V.I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University | Ukraine | 85 |

As we can see, the undisputed leaders on both sides are the national academies of sciences. Without delving into details, this raises questions to the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and its leadership regarding their actions—or lack thereof—in this context. At the same time, 85 joint publications under the affiliation of the Crimean Federal University (which Scopus still lists as Ukrainian) suggest that some part of what appear to be Ukrainian–Russian publications are in fact Russian–Russian, simply presented under the Ukrainian flag.

We wrote earlier about Russia’s use of stolen Ukrainian universities.

In addition, it usually takes more than a year for academic articles submitted to a journal to be published. Finally, some publications appear within large international projects involving dozens or even hundreds of researchers, where Ukrainians and Russians may not interact directly at all.

Next, we will test a few hypotheses:

- Scientific cooperation between Ukraine and Russia is the result of participation in joint international projects—that is, there is no direct collaboration.

- Scientific cooperation between Ukraine and Russia is the result of delays in the publication process—and today, there is no actual collaboration.

- Publications by Russians with other Russians from the occupied territories of Ukraine, under the cover of stolen Ukrainian institutions, may be counted by the Scopus database as collaboration between Ukrainian and Russian scholars.

Let us start with the first hypothesis. In 2024, the Scopus database listed 323 joint publications by Ukrainian and Russian scholars. Of these, 122 were authored by 20 or more researchers. Taking this factor into account, accusations of scientific collaborationism can be dismissed for roughly one third of Ukrainian–Russian publications, since they are actually not. However, this shows that large international projects unfortunately still include Russians. Table 2 illustrates that, on average, about one-third of publications were produced within large global research teams.

Table 2. Number and share of Russian–Ukrainian publications with more than 20 co-authors

| 2022-2025 | 2024 | 2025 | ||||

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Total | 1,803 | 100% | 323 | 100% | 162 | 100% |

| 20 or more co-authors | 635 | 35% | 122 | 38% | 59 | 36% |

Still, more than 1,000 joint publications remain for the period 2022–2025. This leads us to the hypothesis that some Ukrainian–Russian publications are in fact Russian–Russian, with Russian scholars using stolen Ukrainian institutions in the occupied territories to present themselves as Ukrainians. In line with international standards (in particular ISO 3166), the Scopus database labels such institutions as Ukrainian. For example, Scopus marks publications from the Crimean Federal University as Ukrainian—but in reality, these are works by Russian scholars (or by Ukrainians who have betrayed their country).

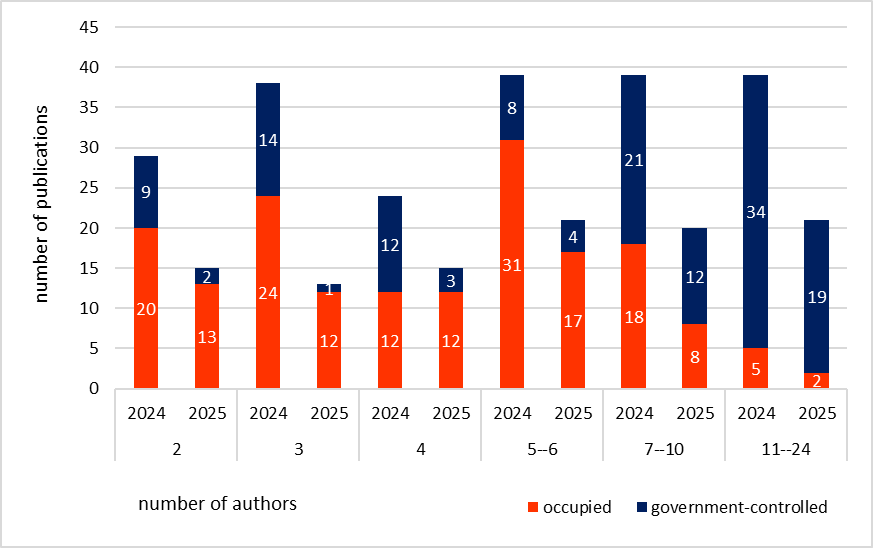

Since there is no automated way to process the database, we manually checked the data for 2024 and 2025, as the years most relevant to the present moment. An additional reason for focusing on this period is that publication lags can last a year or more. In other words, many of the 2022 and even 2023 publications are, in fact, studies from 2021 or earlier. Because this argument is much harder to apply to papers from 2024–2025, we reviewed those years manually. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Estimated number of publications from the occupied territories and from stolen Ukrainian institutions, 2024–2025

As we can see, in publications with 10 or fewer authors, the key factor behind the appearance of joint Ukrainian–Russian papers is not genuine collaboration but rather the use of stolen Ukrainian institutions and territories by Russians to present themselves as Ukrainian scholars. In 2025, in 80–90% of cases where a paper had fewer than seven authors, these were Russian–Russian publications. Thus, the hypothesis of illusory collaboration is partially confirmed.

Interestingly, the percentage of pseudo-Ukrainians drops sharply when the number of co-authors exceeds 10. In other words, representatives of the occupied territories and stolen Ukrainian institutions are rarely included in large international research projects. In such projects, Ukrainians are genuinely present alongside Russians, even if they do not necessarily collaborate directly.

Thus, if we exclude from the set of joint publications those authored by large groups, as well as those authored by Russian scholars affiliated with Ukraine’s occupied territories and stolen Ukrainian institutions, there remain 70 out of 323 publications for 2024 and 22 out of 162 published in the first seven months of 2025.

Therefore, out of nearly 500 joint publications formally reported for 2024–2025, fewer than 100 remain—about one-fifth of what is declared as Ukrainian–Russian scientific cooperation. Hence, more than 80% of what Scopus counts as Ukrainian–Russian publications are, in fact, not such. Still, this leaves 92 publications in 2024–2025 where Ukrainian scholars made a conscious decision to work with representatives of the aggressor state.

We examined these publications in detail. Together with the Ministry of Education and Science (MES), we sent inquiries to the employers of scholars who were co-authors with Russians, requesting an explanation for such collaboration. The deadline for responses was August 28, 2025, so at the time of writing (September 15, 2025), the absence of a reply can be viewed as disregarding the MES letter.

We received 69 official responses, which corresponds to three-quarters of all identified real joint publications. This proportion is high enough to allow extrapolation from this sample to the overall situation.

The list of institutions that ignored the MES letter is provided in Appendix Table D1. The responses we did receive, however, make it possible to draw a number of important conclusions about the nature of joint publications, the reactions of employers to the identified cases, and potential mechanisms for addressing the problem.

We begin with certain caveats and nuances regarding the emergence of joint publications, which became evident in the course of reviewing the organizational responses to the MES inquiries.

Dual affiliations

A partially mitigating factor is that some Russian co-authors have dual affiliations. In practice, this means they no longer work in Russia, they are affiliated with institutions in other countries but for some reason still list Russia as a secondary affiliation (or the Scopus database, by inertia, assigns them an affiliation that is no longer active).

Incorrect affiliations

Some foreign co-authors were mistakenly assigned a Russian affiliation while they are not affiliated with Russia.

Falsified Ukrainian affiliations

A rather common case is the use of Ukrainian affiliations by scholars who have no actual connection to them—in other words, they do not work at the institution they list as their affiliation.

Publication lags

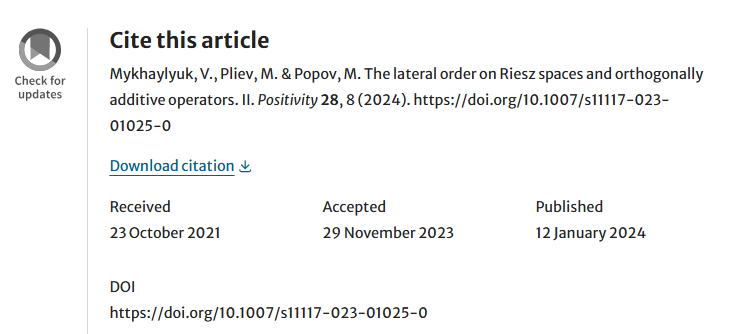

We have already noted that scientific publications are characterized by a lag—that is, the time gap between the research process and the publication of its results. This lag can last for years, which is why the MES focused its inquiries on articles published in 2024–2025. However, the responses to the MES letters make it clear that even papers published in 2024 may have been submitted to journals in 2021 or even earlier.

For example, the article shown in Figure 4 was submitted in October 2021 but published only in January 2024. After 2022, the author had ceased cooperating with Russian scholars.

Figure 4. Example of an article submitted to a journal in 2021 and published in 2024

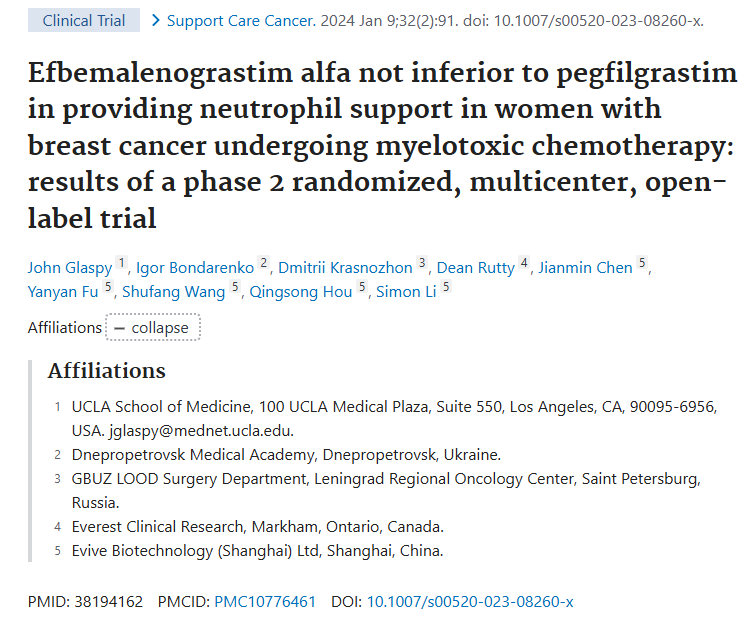

However, this line of argument for the existence of joint works does not always withstand factual scrutiny. For example, the article shown in Figure 5 below was submitted in 2024.

Figure 5. Example of an article submitted in 2024

The article’s metadata indicates that the initial submission date was February 10, 2024—nearly two years after the start of the full-scale invasion. There is only one way to interpret this: deliberate collaboration with representatives of the aggressor state. Moreover, this was a systemic activity, as in 2024 alone, there were five joint articles with Russian co-authors.

The leadership of the Ukrainian scholar’s employer (Odesa State Academy of Civil Engineering and Architecture) stated that its scholars conducted research only in cooperation with Ukrainian colleagues. However, the affiliations of Dmytro Leshchenko’s co-authors are entirely clear (see articles from March 2024, June 2024, February 2024, February 2024-2, and January 2024): they are all Russian institutions. For example, Sergey Yershkov is affiliated with the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics (Moscow); Yevgeny Prosviryakov with the Ural Federal University of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Yekaterinburg); and Natalia Burmasheva with the Institute of Engineering Science, Ural Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Yekaterinburg).

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated case. In the case of the article shown in Figure 6, the response letter to the MES inquiry claimed that it had been written and submitted before the start of the full-scale invasion. In reality, however, it was submitted on February 22, 2024 (!).

Figure 6. Joint article by Ukrainian and Russian scholars, submitted to a journal in 2024

In other words, the author’s employer—the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences—accepted the author’s explanation that the article had been submitted before 2022 without fact-checking. This list could be extended, but it would not provide any fundamentally new information.

Individual positions of certain scholars

The responses to the MES letter highlight another aspect of joint publications that must be taken into account before drawing conclusions. For example, one Ukrainian scholar explained a joint publication with a Russian colleague in the following way:

- My co-author XXX, being a citizen of the Russian Federation, twice signed appeals against Russian aggression and in support for Ukraine (in other words, this person not only supported Ukraine but also took personal risks).

- He is (by birth and passport) a “citizen of the country,” but by no means a “representative of the country.” His position is opposite to that of the Russian state (as noted above).

- The article published the results of a joint study that started before the war.

- My cooperation with XXX is entirely an individual collaboration between two people, with no involvement whatsoever of the aggressor state.

Scholars under occupation

Another specific case is that of a scholar who found himself in occupied territory. Judging by his subsequent actions (co-authoring publications with Russians, resignation from a Ukrainian institution), the Ukrainian scholar sided with the occupiers and chose the path of a collaborator.

Uncoordinated actions of corresponding authors

As a rule, within a team of authors, one person is designated as the corresponding author responsible for submitting the article for publication. The analysis has shown that, in some cases, the corresponding author may introduce unauthorized changes during submission—for example, in co-authors’ affiliations. As a result, a scholar affiliated with the aggressor state may appear in the author list, even though no deliberate collaboration took place.

Falsified co-authorships

We identified several cases when scholars had no involvement in writing a publication at all and were included in the list of authors without their knowledge. For example, in one case, Russian co-authors gained access to the results of a Ukrainian scholar’s research through a joint project. After the Ukrainian scholar cut off all communication and contacts with representatives of Russia, they continued to use the results of the joint research in subsequent publications, adding the Ukrainian scholar’s name to the author list in order to avoid accusations of plagiarism and to maintain a semblance of academic integrity.

International projects

Although in our study we sought to minimize the impact of this factor by limiting the number of co-authors to 10, some respondents noted that their participation in a publication was the result of international research projects, where authors were determined by the project organizers.

In our view, this explanation is entirely valid in cases with dozens or even hundreds of co-authors. However, when the author group is a small “closed circle” (up to 10 co-authors), it looks more like an attempt to avoid responsibility for one’s own actions.

For example, two articles (December 2023 and January 2024) had nine co-authors each, including one Ukrainian scholar. In its explanatory letter, Dnipro State Medical University stated that the co-authors represented hundreds of scholars from dozens of countries, and it was unclear why Russian researchers appeared among them. Since this was a decision made by the project organizers, no Ukrainian scholar bore any responsibility. Thus, according to Tetiana Pertseva, Rector of Dnipro State Medical University and Academician of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, the university scholars do not cooperate with representatives of the aggressor state, although Figure 7 suggests otherwise.

Figure 7. Example of an article with nine co-authors, including both a Ukrainian and a Russian scholar

Being part of an author team is a conscious decision by each scholar and a matter of personal responsibility. One can always prohibit inclusion of his/her name in the author list or submit a request to the journal for removal of the name. Unfortunately, Tetiana Pertseva does not see a problem in Ukrainian scholars publishing together with Russians in 2024, that is, two years after the start of the full-scale invasion. This fact alone underscores the relevance of the research we have implemented.

Specific circumstances

One of the joint articles (in metrology) was published “based on the results of international comparisons of national standards.” Such publications are uploaded automatically. In reality, all the joint work—and any contacts within this project—had ended back in 2019.

Employers’ reactions

What characterizes the system is not so much the mistakes themselves as the response to them. The most typical responses are disciplinary measures such as reprimands or warnings. But there have also been more radical steps, as well as cases of complete inaction. Let us look at the most common reactions.

Reprimand/Warning

An employee who published an article together with representatives of the aggressor state typically receives from their institution an official warning or reprimand as punishment for such collaboration.

Dismissal/Termination of contracts

One university fully terminated its employment relationship with a Doctor of Sciences, Professor.

Non-renewal of contracts

Two universities declined to renew contracts with their staff members. One of them using this precedent adjusted its policy by introducing a direct ban on contracting academic and teaching staff who had engaged in joint scientific activity with representatives of the aggressor state.

Demotion and liquidation of departments

One research institution eliminated an entire laboratory headed by a scholar who had published together with representatives of the aggressor state. Employees who had co-published with Russian scholars were reassigned to a technical department.

Strengthening internal control

Heads of research units were instructed to more thoroughly oversee the formation of author teams that include foreign scholars prior to submitting publications.

Informing foreign partners

Another form of institutional response was to notify foreign partners of the impossibility for Ukrainian scholars to participate in author teams together with representatives of Russia.

Strange reactions

One of the responses to the MES inquiries made it clear that if your husband is Russian and works for the Russian Academy of Sciences (Igor Karachentsev, affiliated with the Special Astrophysical Observatory, a research institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences), then cooperating with Russia is apparently acceptable. At the same time, you can hold a position within the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (Main Astronomical Observatory of NASU), and that institution does not think that five (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) joint publications with Russians in 2024–2025 by an employee is the reason for reprimand or dismissal. Instead, the employee received a note of caution and was “recommended” (!) to “temporarily” (!!) put joint publications on hold. In addition, these articles will not be included in the institution’s annual report. With this approach, it becomes clear why there are still hundreds of joint publications by Ukrainians with representatives of the aggressor state.

No reaction

The most typical pattern of response to MES inquiries is the absence of any real action. In other words, no reprimands, demotions, dismissals, non-renewal of contracts etc. As a rule, the reply is composed of general phrases about inappropriateness of cooperation, adherence to norms, or the importance of oversight, but in reality an institution avoids imposing sanctions, sides with the employee and accepts their explanations even when those explanations do not align with the facts.

Still, institutions’ reactions—or absence thereof—generally do not help resolve the issue. The very fact of a joint publication sends a signal to the world that supports the narrative of Ukrainians and Russians as “brotherly peoples” who communicate seamlessly with each other. Below, we outline the most common practices for addressing this issue.

Practices for addressing the problem

Retraction of a publication or an author

The classic and most effective practice for addressing this kind of problem is retraction (withdrawal) of the publication. Several scholars whom we contacted sent letters to journal editors or publishers requesting retraction. An alternative approach is to request the removal of a scholar’s name from the list of authors.

Letters to publishers requesting affiliation changes

Take, for example, an article co-authored by scholars with Russian affiliations (Figures 8A, 8B). At the first glance, this looks like a classic joint publication between Ukrainians and representatives of the aggressor state. In reality, however, the corresponding author (a foreign national) had entered incorrect affiliation data without informing the Ukrainian co-authors. After the Ukrainian scholars raised the issue, the corresponding author wrote to the publisher requesting corrections to the affiliations of certain authors. The publisher resolved the matter favorably: Russians were replaced by “independent researchers” (much like “neutral athletes”).

Figure 8A. Original author affiliations

Figure 8B. Corrected author affiliations

In other cases, co-authors had dual affiliations, one of which was Russian, and this outdated information was automatically provided by the system. In response to the written requests to remove the Russian affiliation, publishers deleted it.

Letters to scientometric databases

A Ukrainian scholar was included in the list of authors, along with Russians, without his knowledge. He wrote to Scopus requesting that the publication be removed from his profile. Similar approaches were mentioned in other responses to MES inquiries. However, this does not resolve the issue, since the article remains in the database along with all the authors and their affiliations.

The Acknowledgements section

Notable are cases when representatives of the aggressor state appear among the authors even though no actual cooperation took place (typically within international projects). In such cases, the Acknowledgements section may clarify that the Ukrainian scholar had no communication or joint work with Russian researchers during the preparation of the publication or the course of the research. For example: “…declares that he had discussions exclusively with the corresponding authors.”

Thus, the problem of joint publications by Ukrainians and Russians does indeed exist, although its actual scale is an order of magnitude smaller than one might assume from Scopus data. While the issue may appear binary at the first glance (a publication either exists or does not), in reality, it comes with a range of specific nuances that must be carefully examined before labeling any scholar a scientific collaborator.

Solving this problem requires a comprehensive approach, combining the individual actions and personal responsibility of Ukrainian scholars with policies of the institutions they represent. The most effective solution remains a retraction of an article or removal of the Ukrainian author from the author list.

However, joint publications are only one aspect of scientific “brotherhood”. Another, no less important, manifestation is the presence of Ukrainian scholars on the editorial boards of Russian journals.

Editorial boards

The editorial board is the heart and face of a journal: it gives the publication its scientific legitimacy and reputation. Its composition is therefore crucial—and it is the first thing potential authors look at.

We examined the editorial boards of about 800 Russian journals (those indexed in Scopus, meaning at least minimally represented in the international research space). The results were discouraging: as of July 2025, more than 90 scholars with Ukrainian affiliations were listed as active members of the editorial boards of Russian journals.

Even taking into account Russia’s policy of “dead souls”—8 Ukrainians (about 9% of the total) listed as board members of Russian journals are in fact deceased (some since 2016)—and the presence of several outright traitors (4 collaborators, or 4% of the total, such as Mykola Vatutin and Viktor Variukhin, who work for the occupiers in Donetsk, and Ihor Dovhal, who serves them in Crimea)— about 80 scholars remain.

Based on our study of the editorial boards of Russian journals, we can assume that about 70% of the listed members are not active at all—in other words, the data are entirely or partially falsified.

To test this hypothesis, we, together with the MES, sent formal inquiry letters to the employers of Ukrainian scholars listed as members of Russian journal editorial boards. To the 79 letters sent, we received 52 replies (65%). The list of institutions that ignored the MES inquiry regarding their employees’ participation in Russian journal editorial boards is provided, in Appendix Table D1.

Only in one of the 52 cases did a scholar confirm actually being a member of a Russian journal’s editorial board—explaining that the journal was, in fact, no longer Russian: the editor-in-chief had left Russia for Belgium, and the journal was planning to transfer its jurisdiction from Russia to Kazakhstan. The rest (apart from a few evasive responses) stated outright that they did not perform any editorial board duties or that they had no idea of being listed as members in the first place.

In 35 of the 52 cases, the replies contained direct confirmation that the Ukrainian scholar’s editorial board membership had been falsified. Not a single response indicated that even one Ukrainian scholar had implemented editorial duties since 2022. This suggests deliberate falsification of editorial boards by journals from the aggressor state. Some scholars had already sent letters requesting removal from editorial boards even before the MES inquiry. The typical response of Russian journals was to ignore such requests.

The standard way of addressing the problem of a Ukrainian scholar being listed on the editorial board of a Russian journal is for the scholar to send a formal letter to the journal demanding removal from the board. In addition, the scholar may write directly to the journal’s publisher.

Possible ways to address the problem of scientific “brotherhood”

Relying on the “raw” data from Scopus can produce a radically misleading picture of the scale of collaboration between Ukrainian and Russian scholars, since Scopus indexes articles by scholars from occupied territories and stolen Ukrainian institutions as Ukrainian.

Secondly, a considerable number of international scientific projects still involve both Ukrainian and Russian scholars, resulting in joint publications that create the illusion of collaboration. Another issue is the (largely falsified) presence of Ukrainian scholars on the editorial boards of Russian journals. Yet the core problem lies in the deliberate choice of some Ukrainian scholars to publish together with Russians.

What are possible ways to address these problems?

The problem of mimicry

The primary source of the illusion of collaboration is that Russian scholars present themselves as Ukrainians by affiliating with institutions in occupied territories and with stolen Ukrainian academic organizations.

On the one hand, Scopus is correct to classify occupied territories and stolen institutions as Ukrainian. This aligns with international law, specifically the ISO 3166 standard. However, there must also be a second step: if Ukrainians did not write a given article, then it should not appear in the Scopus database. In other words, an article authored by Russians in occupied Crimea or Donetsk under the name of a stolen Ukrainian university or research institution should not be indexed as having a Ukrainian affiliation at all—because in reality, no Ukrainian affiliation exists.

To address this problem, we propose that Scopus introduce a rule stipulating that the database will not index publications from occupied territories, stolen Ukrainian institutions, or stolen Ukrainian journals without an explicit consent from Ukraine.

The first step should be removing all stolen Ukrainian institutions and journals from Scopus, with the support of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. The next step should involve either retracting already indexed articles or reclassifying the affiliations of Russian authors and authors from occupied institutions as neutral—that is, without indicating any country or institution. This would prevent Ukraine’s name from being used against it.

The problem of dual affiliation

Ukrainian authors must pay more attention to their co-authors’ affiliations. If a former Russian scholar, now working in the United Kingdom or the United States, lists Russia as a secondary affiliation, Ukrainian scholars should condition their co-authorship on removal of that second (Russian) affiliation.

Large international projects

We propose following the CERN model—or the analogy of major sports: there are no Russian scholars or athletes, only neutral individuals without a flag or affiliation. In this way, individual researchers are not subjected to authorship-related restrictions or discrimination, but Russia, as an aggressor state and an uncivilized country, is excluded from the context of the civilized scientific world.

Learning from mistakes

Learning from mistakes is essential: Ukrainian scholars who have engaged in any form of scientific collaboration with Russia, along with their employers, must acknowledge the problem and take corrective actions.

Retraction of articles/authors

When it comes to joint publications, the primary mechanism should be retraction: ideally, the retraction of the entire article (including those written before 2022), or at the very least the removal of the Ukrainian scholar’s name from the list of co-authors.

Consider a specific example. The article Teslyk et al. (2022) records that the authors Olena Teslyk (Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv) and Lidiia Zadorozhna (Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv) requested that their names be removed from the list of authors. Today, their names no longer appear in the list of authors. We do not know the reasons behind this decision, but one of the article’s co-authors is Evgeny Zabrodin, affiliated with the Skobeltsyn Institute of Nuclear Physics, Moscow State University.

It is quite telling, however, that Maksym Teslyk, affiliated with the Faculty of Physics at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, chose to remain on the list of authors alongside Evgeny Zabrodin. Today, Maksym Teslyk works in the Department of Applied Physics and Higher Mathematics at the Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design.

To be fair, in another article, submitted to a journal in August 2023, Evgeny Zabrodin (Skobeltsyn Institute of Nuclear Physics, Moscow State University) appears together not only with Maksym Teslyk (Department of Applied Physics and Higher Mathematics, Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design), but also with Olena Teslyk (Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv).

Withdrawal from editorial boards

If a Ukrainian scholar believes their inclusion on the editorial board of a Russian journal is inaccurate, they can contact the journal with a demand to be removed, and, of course, monitor the process by periodically checking whether their name has in fact been deleted from the list of board members. In addition, they may inform other board members and the publisher of their position.

Monitoring, compliance, and the role of the MES

An essential element of any systemic effort is oversight. Accordingly, the MES, as the body responsible for science in Ukraine, must conduct regular monitoring of Russian–Ukrainian scientific collaboration and take appropriate measures—ranging from inquiry letters requesting clarification of specific cases to sanctions such as dismissal, reprimands, or demotions—against scientific collaborators.

Conclusions

The problem of scientific “brotherhood” (collaboration between Ukrainian and Russian researchers) persists even after three and a half years of full-scale war. Although it is largely an illusion, to an outside observer unfamiliar with the details it appears as thousands of joint Ukrainian–Russian articles and dozens of Ukrainian scholars—including academicians, professors, and directors of research institutes—serving on the editorial boards of Russian journals. This aligns with Russian propaganda about “brotherly nations,” complicates the introduction of new sanctions against the aggressor state, and significantly weakens Ukraine’s position in urging the international community, including the academic sphere, to cut ties with Russia.

We have demonstrated that the actual extent of Ukrainian–Russian scientific cooperation is much smaller than it seems at first glance, since a significant share is generated by Russian researchers masquerading as Ukrainians, using occupied Ukrainian territories and stolen Ukrainian institutions for this purpose. In addition, Russian journals openly falsify their editorial board memberships, often illegally listing Ukrainian scholars. Another aspect is the participation of both Ukrainians and Russians in large international projects involving dozens or even hundreds of researchers, which does not necessarily imply direct cooperation. In such cases, questions are rather to the organizers of these projects who still collaborate with Russians.

One direct outcome of this study has been a reduction in cooperation between Ukrainians and Russians following letters from the MES: dozens of Ukrainian scholars have contacted Russian journals demanding removal from editorial boards; a number of joint publications have been retracted or entered the retraction process; in several cases scholars’ affiliations have been corrected, resulting in the disappearance of “joint Russian–Ukrainian” publications. Some scholars have faced disciplinary measures for collaboration with Russians, sending a clear signal to the entire Ukrainian academic community about the inappropriateness of cooperation with representatives of the aggressor state. Together, these developments provide hope that instances of scientific collaboration will be eliminated.

Since the problem is complex and manifests at different levels of scientific collaboration, its resolution must involve all stakeholders—from Ukrainian scholars and authorities to international scientometric databases and multinational research projects. The ultimate goal, however, must remain the same: to remove the illusion of cooperation where it exists and to terminate cooperation where it is real.

Appendix

Table D1.

| List of institutions that ignored the MES inquiry regarding joint publications by their employees with Russian researchers | List of institutions that ignored the MES inquiry regarding their employees’ participation on the editorial boards of Russian journals |

| Odesa State Environmental University | Odesa National Medical University |

| Shalimov National Institute of Surgery and Transplantology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine | Ukrainian Institute for Public Health Policy Research |

| Dnipro State Medical University | Dnipro State Medical University |

| National Science Center “Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology” (NSC KIPT) | Zaporizhzhia Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine |

| Odesa National Polytechnic University | National Pyrohov Memorial Medical University, Vinnytsya |

| Kolomiychenko Institute of Otolaryngology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine | Zaporizhzhia State Medical and Pharmaceutical University |

| Institute of Geological Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | Ukrainian State Research and Design Institute of Mining Geology, Geomechanics and Mine Surveying |

| Boholiubov Institute for Theoretical Physics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | Tymoshenko Institute of Mechanics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine |

| Astronomical Observatory of Odesa of I. I. Mechnikov National University | Kyiv Medical University |

| Admiral Makarov National University of Shipbuilding | Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute |

| Sytenko Institute of Spine and Joint Pathology of the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine | Ukrainian Research Institute of Transport Medicine, Ministry of Health of Ukraine |

| Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology | Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics |

| Kyiv National University of Technologies and Design | National Technical University “Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute” |

| Museum of the Book and Printing of Ukraine | Interregional Academy of Personnel Management |

| Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University | |

| Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | |

| Dnipro Metallurgical Institute of the Ukrainian State University of Science and Technology | |

| Bohomolets Institute of Physiology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine | |

| Karazin Kharkiv National University | |

| Lytvynenko Institute of Physical Organic Chemistry and Coal Chemistry of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine |

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations