The blockade is working in sense that it increased prices of grocery products in Crimea: prices appear to have increased by approximately 10 percent more in Crimea than in mainland Ukraine. There is a likely further increase in prices in Crimea. However, the effect appears to be modest and thus unlikely to overturn policies in the occupied Crimea. Tatars announced that they plan to cut supply of electricity from mainland Ukraine to Crimea. This additional blockade may be more damaging to occupants than the truck blockade.

After being annexed by Russia, for a significant part of peninsula’s population, Crimea is gradually turning into an unpleasant place to live. Sanctions limit investment, Visa/Mastercard do not process transactions, transportation to/from Crimea is an ordeal. If this was not enough, Crimean tatars started to block trucks going to the peninsula thus reducing access to Ukrainian goods normally available to consumers in Crimea or Russia. The main idea of the blockade is to make the occupation costlier to Russia. While the PR campaign has been influential, the economic significance of the blockade is not clear. While some claim that limiting the 6,000 tons of food flow in Crimea might have surged prices by as much as 150 percent, others consider the economic effects of the blockade to be negligible. Is it possible to adopt a data-driven approach to estimate whether this barrier to trade raised the cost of doing business or living in Crimea?

Photo: uapress.info

To answer this question, we examine the dynamics of retail and wholesales prices in Crimea around the start of the blockade. Economic theory predicts that an effective trade barrier between locations A and B should create a disparity (“wedge”) in the level of prices in A and B. If location A is an importer from location B and B is larger than A, a barrier should generate a level of prices in A higher than that in B which means lower quality of life in location A. On the other hand, if there is no barrier, the law of one price should hold: a given good should be sold for the same price across locations (after adjusting for differences in tax codes, legislations, possible custom duties). Otherwise, there are arbitrage opportunities and unexploited profits. Thus, if we want to measure changes in welfare and effectiveness of the blockade, we need to study the dynamics of price quotes for identical goods sold in Crimea and Ukraine. If prices became higher in Crimea than in mainland Ukraine, the blockade is working.

Unfortunately, most price data at the geographically disaggregate level are available at low frequencies (monthly or annual) and hence not suited for analyzing adjustment of prices at the daily or weekly frequency. In addition, the statistical agencies in Ukraine and the occupied Crimea can sample different goods while constructing price indices. However, there are alternatives to official data. For example, the wholesale agricultural market in Simferopol (http://privoz-crimea.com) provides daily data on retail and wholesale prices for a number of grocery products at a very detailed level and so we can have a good guess if a product is local to Crimea or if it is imported . For example, the list of the products covers about 100 products, including lemons (not grown in Crimea and imported through either mainland Ukraine or Russia), plums (grown in Crimea), beets (imported from mainland Ukraine or Russia).

From 25.08.2015 till 18.10.2015 we collected wholesale and retail price ranges (minimum and maximum) denominated in Russian rubles. As data were not updated over weekends we exclude all Saturdays and Sundays. To maintain a relatively stable composition of goods over our time span, we also removed all goods that were traded over less than 20 days (e.g. baby potato). After the screenings we have 98 products, 88 of which were traded during each of 37 observation dates.

We do not have comparable data for a Ukrainian city and, as a result, we will only be able to examine if prices for grocery products increased relative to the pre-blockade level. However, the time period we study is September-October. During this time span the consumer price index in September for mainland Ukraine increased only 1 percent for vegetables and 6 percent for fruit relative to August. Hence, the behavior of the benchmark prices in mainland Ukraine has been relatively stable. Furthermore, price reaction to blockade is not likely to be affected by the exchange rate RUB/UAH, as it was in the range 3.05-3.10 from the end of August till the first week of October.

There is a great deal of heterogeneity in the dynamics of prices (see Table 1). Some items had dramatic price declines, while others experience large price hikes. Because the behavior of prices for each product is often determined by product-specific factors and there is substitution across products, in the rest of our analysis we focus on equally weighted “price indices” which capture the average dynamics

Table 1. Top 5 price declines/increases

| name | % | name | % | |

| 1 | Chinese cabbage | -83.39% | Courgettes | 92.99% |

| 2 | Green radish | -63.80% | Tomatoes | 76.89% |

| 3 | Chilly | -36.07% | Aubergine | 76.11% |

| 4 | Mandarine | -33.88% | Cauliflower | 69.31% |

| 5 | Pomegranate | -33.04% | Plum tomatoes | 69.17% |

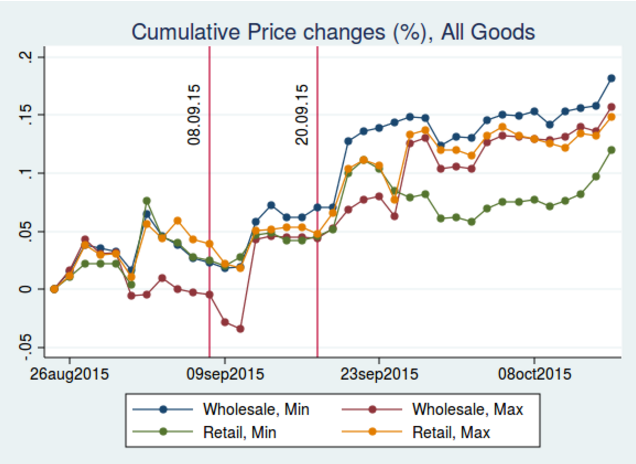

Figure 1 plots time series for the average cumulative price change across index. Each “price index” is normalized to start at zero at the end of August. Based on our price ranges, we define four types of prices: minimum retail price, maximum retail price, minimum wholesale price, maximum wholesale price. Although there is some variation across price indices, there is a consistent pattern in the data. Prices increased at the time the blockade was announced (September 8, 2015; the first vertical line in the figure) and then again when the blockade was implemented (September 20, 2015; the second vertical line in the figure). Depending on the price series, the level of prices increased by 10 to 18 percent since early September. While this magnitude is larger than the inflation we observe for mainland Ukraine, the price hike in Crimea is not shocking and, perhaps, not as large—at least for now—as the tatars hoped.

Figure 1. Cumulative Price changes

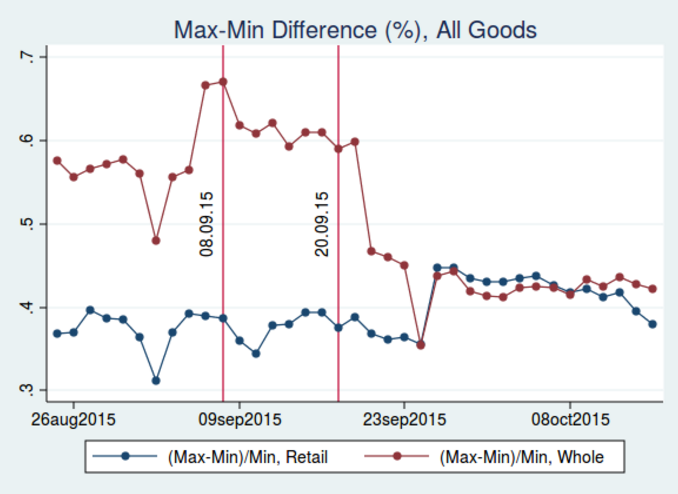

There are signs that more price increases are coming in Crimea. First, profit margins (measured as the percentage difference between retail and wholesale prices) declined since the peak levels in early September. This suggests that some of the price shock due to the blockade was absorbed by retailers. This adjustment is likely not sustainable in the longer run and thus the profit margins are likely to rise in the future. Because Crimea can hardly influence wholesale prices (it is a small market relative to Ukraine or Russia), rising profit margins should translate into higher retail prices.

Figure 2. Profit margin

Second, the distribution of wholesale prices in Crimea for these products (measured as the percentage difference between maximum and minimum prices for goods in a given product category) became more compressed. A likely explanation is that high-quality goods within each product group exited the market which eliminated the high-end of the price distribution. To the extent these higher-quality goods are going to return to Crimea, one should expect a further increase in the level of prices effectively paid by consumers.

Figure 3. Price dispersion

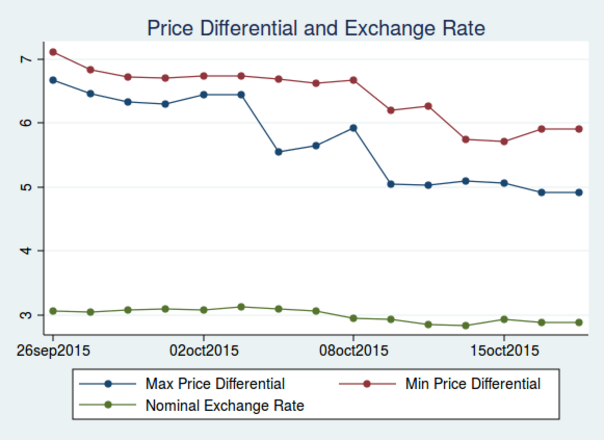

While we do not have pre-blockade prices for mainland Ukraine, we collected data from Nejdanyj wholesale market in Kherson region (http://www.nejdana.in.ua/) during the post-blockade period, 26.09.15 to 18.10.15. Using these data, we calculate price ratios ( “effective exchange rate”) (Price RUB/ Price UAH) for identical product categories in both Kherson and Simferopol. For example, if the minimum wholesale price of one kilogram watermelon in Kherson is 1 UAH, while the minimum wholesale price of watermelon in Simferopol is 12 RUB, price differential is a factor of 12. This magnitude is substantially larger than official exchange rate of 2.88 RUB/UAH which indicates huge profit opportunities. That is, buying 1 kg of melon in Kherson would cost only 1 UAH and selling it in Simferopol would generate 12 RUB /(2.88 RUB/UAH)=4.17 UAH thus giving a profit of more than 3 UAH. Figure 4 reports dynamics of price differential (the ratio of Crimean prices to Ukrainian prices) for minimum and maximum prices. Even though we observe downward trend in price differential (from 7 to about 5.5), disparity in price levels remains large. This likely provides incentives for smugglers to use water transport for delivering goods to Crimean markets.

Figure 4. Price differentials and exchange rates

In summary, the blockade is working in sense that it increased prices of grocery products in Crimea: prices appear to have increased by approximately 10 percent more in Crimea than in mainland Ukraine. There is a likely further increase in prices in Crimea. However, the effect appears to be modest and thus unlikely to overturn policies in the occupied Crimea. Tatars announced that they plan to cut supply of electricity from mainland Ukraine to Crimea. Given how inelastic demand for electricity is and limited capacity to cheaply generate electricity in Crimea, this additional blockade may be more damaging to occupants than the truck blockade.

The Crimea Week

Crimea Triangle: Where do Missing Trucks from Ukraine Go? (Yuriy Gorodnichenko (UC Berkeley) and Oleksandr Talavera (U Sheffield), co-founders of VoxUkraine)

The Geostrategic Games around the Word «Investment» in Crimea (Ridvan Bari Urcosta, political scientist)

How the Chinese Government and French Conservatives Are Helping Russia to Undermine Humanity’s Non-Proliferation Regime (Andreas Umland, Dr. phil., Ph. D., Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Euro-Atlantic Cooperation in Kyiv and General Editor of the book series “Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society“)

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations