In March 2020, the NBU spent more than $2 billion out of the foreign exchange reserves to smooth exchange rate fluctuations. The speed with which the external assets of the Ukrainian central bank declined alarmed many, and for some it became an invitation to the world of familiar alarmism in “we are doomed” style.

However, there are grounds for caution about interventions of this magnitude. In Ukraine, macrofinancial stability has been associated with exchange rate stability for a long time. Loss of reserves is mostly perceived as a negative signal. Uncertainty about the scale and depth of the crown crisis has been and remains enormous, and the first forecast calculations of the dynamics of macroeconomic indicators for most countries appeared only in the second half of April. In those circumstances, it was difficult to determine in advance whether the NBU’s policy to support the hryvnia by reducing the reserves was smart or not. On the one hand, if the crisis were perceived as a strong long-term shock, perhaps the best choice would be to allow the exchange rate to fall and keep the reserves in case the situation worsens further. On the other hand, if the crisis is perceived as a transitional shock with a subsequent V-shaped recovery, the rapid neutralization of the hectic demand for foreign currency through large-scale interventions looks like a winning option: stabilization of expectations allowed to better prepare the fiscal and banking sectors to the depositors’ raid on financial institutions.

This is not the first year of inflation targeting in Ukraine. Economic agents should get used to exchange rate fluctuations, as well as to fluctuations in foreign exchange reserves. However, it is the uniqueness of the situation that has shown that foreign exchange reserves remain in focus. In the first moments of the crisis, it is chained to them much more than the discount rate. There are grounds for this: criticism of the insufficient accumulation of reserves during 2019; increasing vulnerability to reverse capital flows due to the reorientation of the Ministry of Finance to domestic sources of borrowing; uncertainty regarding negotiations with official creditors (at that time); the slowdown in the domestic economy and the traditional appointment of monetary policy to blame. Taken together, these political and economic factors have sharpened attention to how the NBU has responded to the shock associated with the coronacrisis. The question arises — to what extent the reduction of reserves by $2 billion fits into the experience of emerging markets, and to what extent is such a reaction comparable to the experience of other inflation-targeting central banks? The first month of the crisis is important because it shows the reaction in the conditions of the highest uncertainty. Therefore, in this article we focus on developments in March.

Shock and response options: why is it important to understand the role of foreign exchange reserves?

The first month of the coronacrisis (March 2020) in the global economy is particularly important for several reasons.

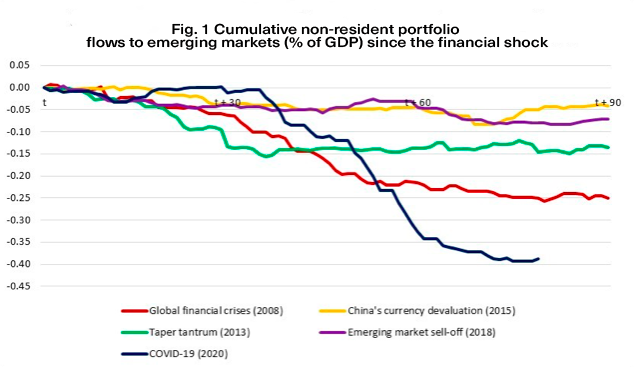

First, it was during this period that the reversal of capital flows in the global economy clearly crystallized. The outflow of capital from emerging markets (EM) was the complete opposite of 2019, which was characterized by an expansion of investment in corporate instruments and medium- and long-term sovereign debt of EM countries. The scale of the outflow has repeatedly been characterized as unprecedented. Fig. 1. clearly indicates that capital outflows have significantly exceeded the previous sad record of the global financial crisis.

Source: IMF data.

Secondly, in the conditions of strong pressure on the exchange rate, the central bank always has a dilemma — to allow a correction of the exchange rate or to conduct interventions to support it. In the first case, monetary authorities are limited by how the change in the exchange rate will affect future inflation and financial stability. The latter is especially important in light of the problems with the dollarization of liabilities. Negative balance sheet effects can shake confidence in the solvency of companies and financial institutions. The weak point of interventions is that their volume is always limited by the physical stock of dollar liquidity (in some cases — the ability to enlist the support of external creditors). In the case of prolonged pressure in the foreign exchange market, foreign exchange reserves are insufficient. These are cases of so-called double drain, when residents add to the withdrawal of capital by non-residents.

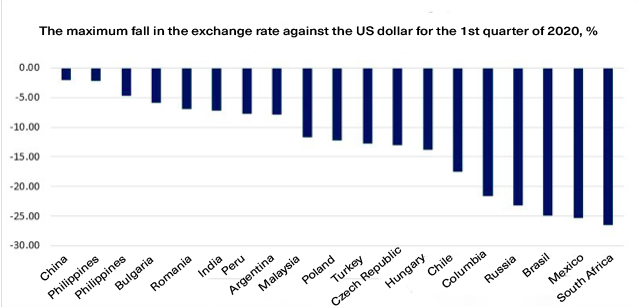

In March 2020, emerging markets faced strong external pressures. Fig. 2. demonstrates that the depth of exchange rate correction in such countries can be described as a currency shock. Also the data of fig. 2. show that the exchange rate reaction turned out to be a natural choice of inflation-targeting central banks. In other words, the exchange rate softened the blow from a significant outflow of capital.

Source: IMF data.

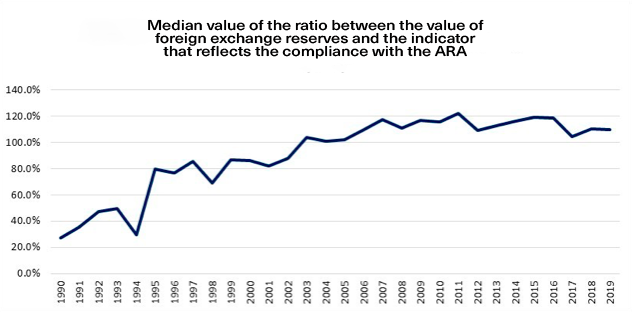

If inflation targeting countries have already reached such a level of exchange rate flexibility that it can take the brunt of capital outflows, then why does the focus continue to focus on foreign exchange reserves? Fig. 3. demonstrates that, despite the long experience of structural reforms aimed at developing financial markets and adjusting to a floating exchange rate, the role of foreign exchange reserves is not declining. They have grown significantly since the early 1990s. However, after 2011 their growth in the categories of compliance with the ARA (Adequacy Reserves Assessment) stopped.

Source: IMF data. ARA — Adequacy Reserves Assessment — a special tool developed by the IMF to assess the adequacy of foreign exchange reserves, taking into account the size of exports, external debt and coverage of domestic monetary aggregate adjusted for exchange rate, capital flows and commodity exports

Emerging market countries are increasing openness faster than they can build up reserves. And rather than further accumulation, it seems appropriate given the fiscal losses from owning significant external assets. That is, with increasing openness, the potential vulnerability does not decrease, in contrast to the ability to compensate for its further accumulation of reserves. This means that countries must adapt to global shocks through more complex institutional arrangements than the physical accumulation of foreign exchange reserves.

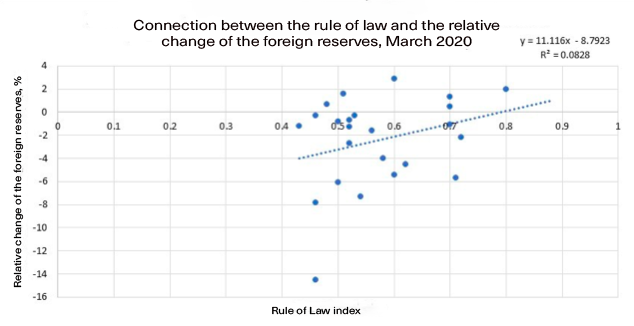

Improving the quality of institutions to deepen the financial system is a key element in adapting to a life with a more open economy and a more flexible exchange rate. Equally important is the rule of law in order to create the political preconditions for the proper conduct of regulators whose actions would prevent the accumulation of financial imbalances and concomitant external vulnerabilities. Foreign exchange reserves continue to play an important role in ensuring macrofinancial stability. But if the country relies solely on them, then the quality of institutions is clearly not commensurate with the needs of global integration. The response to the shock with reserves is indicative of the extent of previous structural distortions, the weakness of policies and the lack of reforms aimed at correcting the above.

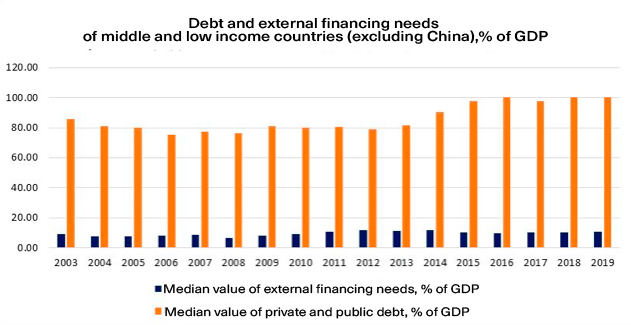

Third, emerging markets have become more open to the effects of financial shocks. The environment of low interest rates, formed after the global financial crisis, has significantly shifted towards debt financing in both the corporate and public sectors (Fig. 4). Not surprisingly, external financing needs have also increased. Compared to 2008, they increased almost 1.5 times. Thus, this group of countries has become much more sensitive to external stresses, even compared to a decade ago.

Source: IMF data.

It is clear that in the case of growing financial openness and given the propensity for debt financing, global investors continue to compare the country’s resilience to external shocks with the amount of accumulated reserves. They also know that for middle- and low-income countries, there is a dilemma between choosing a more pronounced response to a shock through the exchange rate or through reserves. They also know the political context of central banks in weak institutions. Thus, it is no coincidence that reserves have retained their place among the indicators of assessing the resilience of countries.

How did foreign exchange reserves decline in the first month of the crisis in different countries?

Why do we pay special attention to the first month of the crisis — March? Because during it the reversal of capital flows was finally formed. It is at such moments that central banks experience the greatest and, in fact, sudden pressure in the foreign exchange market. It was during the first month that the highest level of uncertainty about the profile of the crisis and its scale took place, which deepened the problem of choosing from the available options for responding to the shock. It was during this period that the excitement of global players and residents regarding the behavior of central banks became most acute. It is quite natural that the external vulnerability accumulated during the previous period should have been most pronounced at this time.

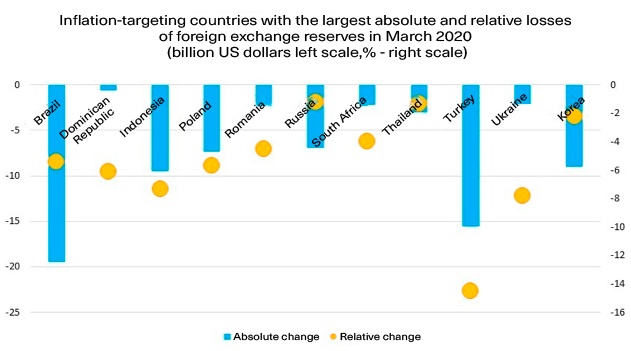

It was during March that the NBU reduced its reserves by $ 2 billion. But what does this mean in the international context? Consider countries where there has been a similar decline in reserves, namely: (1) an absolute reduction in reserves of more than $ 2 billion. USA, and (2) relative — more than 5% of pre-crisis value. Consider the 27 countries that target inflation + Argentina. The group includes Australia and New Zealand, but Norway, Canada and Sweden are not taken into account due to the fact that they have the most developed financial systems that allow the course to work better as a channel for adaptation to shock; this group does not cover all inflation targets (eg Ghana, Jamaica, Albania, etc.) due to limited disaggregated data. Fig. 5 demonstrates that the set of countries turned out to be quite diverse, albeit with the presence of traditional “heroes” of investment news.

Source. Author’s calculations based on IMF data.

As can be seen from Fig. 5, the largest absolute loss of reserves was suffered by Brazil, and the largest relative — Turkey. Russia and Korea have lost almost 10 billion, which is a lot in absolute terms, but not critical in relative terms. In Indonesia, there is a noticeable both absolute and relative decline in reserves. Thus, the reduction of reserves in Ukraine by 2 billion fits into the general trend. But in relative terms, our country is second only to Turkey, whose ambiguous policies have made investors even more nervous. This indicates that the exchange rate response potential remains limited. In the event of a stronger shock, Ukraine could face much more threatening pressure on the central bank’s external assets. On the other hand, controversial policies (such as quantitative easing against capital outflow risks) that highlight structural and financial imbalances, as in the case of Turkey, are an extremely dangerous ingredient in the unfolding of a financial shock.

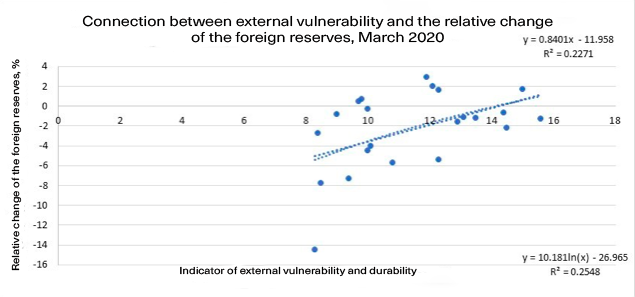

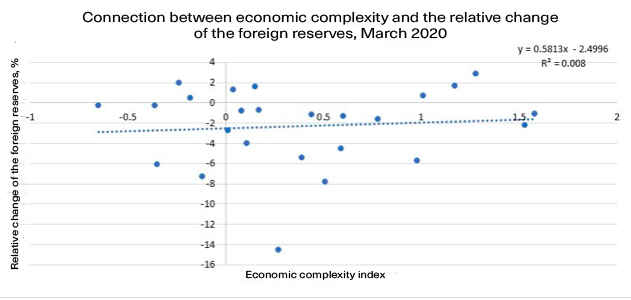

Which factor is most associated with the reduction of reserves? Accumulated external vulnerability is a representative indicator of how much a country has been forced to rely on its external assets. As commodity prices respond feverishly to global stresses, and countries’ vulnerability to fluctuations reverses to the level of economic diversification, it can be assumed that the more diversified the economy, the less the country will need a reserve response to shock, even if it is a supply shock. Instead, the stronger the institutions, the better safeguards the country has against the accumulation of imbalances. Qualitative institutions improve the conditions for financial development, thereby reducing dependence on foreign exchange reserves as the first “line of defense” against shock. The data in Fig. 2 and 5 showed that countries can respond to shock by combining reserves and the exchange rate. However, the country’s ability to reduce its reserves will point to a lack of structural flexibility in the financial sector and vulnerability to the accumulated risks of global shocks.

Fig. 6-8 show that the most important variable that characterizes the fall in reserves in the first month of the crisis is the indicator Scope External Vulnerability and Resilience, which combines 4 indicators of external vulnerability and 4 indicators of the ability to withstand crises (Fig. 6). The Index of Economic Complexity, chosen to reflect the degree of differentiation of economies, did not show any explanatory ability at all (Fig. 7). Thus, in the current crisis, the structure of the economy or the structure of exports are not prerequisites for greater vulnerability to external shocks. In other words, the structure of exports does not automatically cause an economic crisis. Much more important is how the quality of economic policy, the political institutions that support effective policies, the institutions that inhibit the accumulation of significant risks, interact and prevent the generation of external vulnerabilities. The rule of law index correlates more with the amount of loss of reserves (Fig. 8) than the index of economic complexity, although it is also inferior to the variable that characterizes the external vulnerability.

Source: own calculations based on IMF data (International Exchange Reserve Statistics) and Economic Complexity Data Map.

Source: own calculations based on IMF data (International Exchange Reserve Statistics) and World Bank data (World Development Indicators).

Source: own calculations based on IMF data (International Exchange Reserve Statistics) and World Bank data (World Development Indicators).

From fig. 6-8 the following conclusions follow. First, economic agents clearly identify countries’ external vulnerabilities and their ability to withstand crises. This means that with the level of information available, it is difficult to create a “surprise” for the markets and beat them. In the event of destabilization, the pressure on the foreign exchange market first arises in those countries that have accumulated significant financial imbalances and structural distortions, which grow into external vulnerabilities.

Second, the politico-economic and institutional quality of safeguards against the accumulation of external vulnerability comes to the fore in situations of the most acute phase of global shock. If economic agents do not trust the country’s economic policy, are uncertain about the future economic course of the country, they first want to get out of the assets associated with it. Even if regulators in such countries are sufficiently independent and professional, it is political and economic weakness that makes such regulators vulnerable to politically motivated interventions, which are negatively perceived by markets.

Third, global integration does not automatically generate incentives for more prudent policies. For example, due to endogenous changes in risk appetite. Therefore, if such incentives are weak and institutional safeguards for the accumulation of external vulnerabilities remain undeveloped, the force of the shock increases. It is in such cases that foreign exchange reserves come to the fore as a channel of adaptation to global shock. The country cannot rely solely on the exchange rate due to insufficient financial depth, which, in turn, has no impetus to increase due to the weakness of institutions.

Fourth, as shown by the case of Ukraine, where in the first month of the crisis residents put more pressure on the foreign exchange market than non-residents, if there are doubts about political and economic guarantees of access to international liquidity due to, for example, independent central bank under political pressure, losses foreign exchange reserves can be significant. And the case of Turkey stressed that the loss of reserves may be on a scale that does not preclude further strengthening of negative devaluation expectations.

Fifth, foreign exchange reserves continue to be an important component of the macro-financial stability mechanism, but this is more typical for countries that cannot embark on an alternative institutional trajectory, which is characterized by the creation of preconditions for deepening the financial system and incentives to prevent the accumulation of significant external vulnerabilities.

Conclusions

One month, of course, is not enough to analyze the optimal choice of policy instruments to respond to shock and further counter the crisis. However, the specific context of the pressure on the foreign exchange market in March 2020 requires international comparisons and an understanding of the institutional nature of the reduction of foreign exchange reserves in some cases. Foreign exchange interventions to support the exchange rate continue to be on trend, and the scale of the decline in the NBU’s external assets used for this purpose is comparable to that in other countries. However, if economic agents clearly assess the extent of a country’s external vulnerability and its ability to adapt to global shocks, the pressure on the foreign exchange market is natural.

However, such pressure is a reflection of a more complex manifestation of political, economic and institutional factors, which manifests itself in the accumulation of financial imbalances and structural distortions, as well as a lack of confidence in economic policy, which is highly sensitive to political macroeconomic instability. The scale of the loss of reserves is a continuation of the story of how distrust of the central bank’s political environment complicates the latter’s ability to minimize the negative effects of the global shock. In addition, this scale is evidence that the quality of institutions has been insufficient for the financial depth to expect greater exchange rate flexibility as the first line of defense.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations