Recently, an analysis of possibilities the pandemic creates for the democratic development of modern political communities was published at VoxUkraine website. Its author Kyrylo Pasenyuk is right: during the crisis of the national systems of public healthcare and a range of other associated crises, populists lose their influence on political processes.

The arguments Mr. Pasenyuk offers convince that populists cannot remain in their usual positions while faced with the matters of life and death. Indeed, experts and politicians who base their strategies on sound scientific and expert advice have increased their influence to a certain extent in some countries, while the populist politicians (such as Trump and Bolsonaro) have lost some of their popularity. Finally, there is every reason to agree that “in an optimistic scenario, a pandemic could become a factor that could create a demand for expert governance”.

I profess and support a critical approach towards the quality of politics in contemporary political communities. This quality is characterised by the ever decreasing role of public rationality and elements of rule of law, as well as by growing emotionality, destructive irrationality and de-modernizing impact. However, I am not sure that “expert governance” is a way to renew and revive vibrant liberal and social democracy. Realpolitik of the expert rule restricts the rights and freedoms of citizens, destroys the representative force of democracy and undermines political communication by establishing hierarchy of “expert — inexpert”. Thus, such governance cannot be called an “optimistic scenario”. However I repeat: political regimes and systems gain from a bigger weight of institutions and rationality than we see it today. The danger arises when rationality and institutionalization become the goals of political development, and political power ends up in the hands of self-declared “experts”.

As for the idea that the current pandemic and related political and economic crises can have some positive effect on the quality of politics, which is present in the analysis of Mr. Pasenyuk, and in numerous articles by political scientists, philosophers and economists, I agree with it: the existential challenge of pandemic forces citizens to politically engage into social, demographic and economic processes.

But it is important to consider two aspects: (1) the resumption of political competition after the quarantine made it much more affective or emotional, and (2) the political choice has changed under the influence of the pandemic.

Richard Youngs has published an important analysis of how existing political systems emerge from quarantine. He demonstrates that in democratic societies, the return to normalcy occurs as a new, much deeper, political polarization under pressure from governments for the full restoration of freedoms and socio-economic recovery. In particular, he provides convincing evidence of how right-wing radicals, using democratic rhetoric, capture hegemony in matters of democracy and rights, while progressive forces take too much care of the economy.

But Youngs does not notice that the emotional nature of the “post-quarantine” politics also applies to the radicalization of the left. The anti-racist movements of the West are an example of such radicalization. In some countries, these movements may somewhat improve the situation with social equality for better. But in the countries where right-wing populists were already in power and they began to lose ground due to the epidemic, these movements frightened the rich and the remnants of the “middle class,” which create demand for a “strong hand” and far right political choice. Therefore, the rationalizing and democratizing effect of the epidemic can be lost due to this explosion of the protest energy.

Highly emotional radical politics is just a short-term reaction to the government sovereigntist attempts (i.e., attempts to put the interests of the nation above the universal norms and the international law), in ten or twenty years the choice of the future political communities will likely be related to the answer each of the countries give to biopolitical trilemma.

In the context of this conversation, biopolitics is a political practice aimed at securing, supporting and increasing their populations. The specificity of biopolitics is that it provides the state with the legitimacy to treat citizens not as holders of inalienable rights and freedoms, but as a biological specimen of the Homo sapiens living in the government-controlled areas. Therefore, the sovereignty of the citizen is denied, and the sovereignty of the government is absolutized. Biopolitcs legitimizes a ruling group to deprive citizens of their rights to their body and life, as well as to control, for example, sexual life of individuals (at what age it is permitted to start it, between which groups, genders and sexes it is permitted, etc.), abortion, vaccination, access to health care services, euthanasia, and/or quarantine. Aso, such ruling groups actively promote the benefit of their political care to the controlled population, and many philosophers (for example, Giorgio Agamben) write about the dangers of care that deprives a person of protective “clothing” of their freedoms.

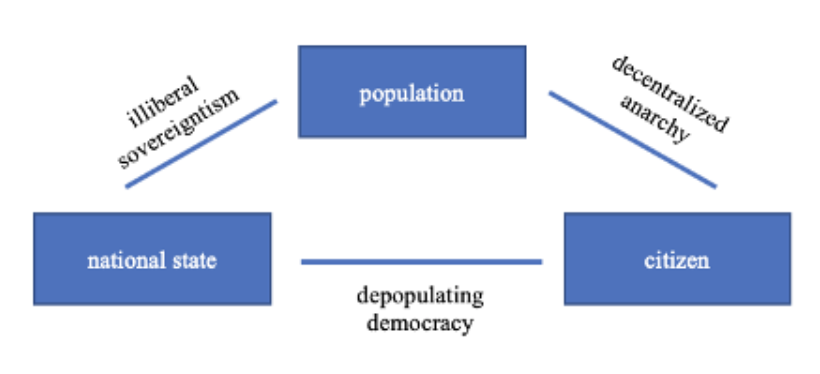

Due to the pandemic effects, the choice in political communities is prescribed in a way that can be modeled as trilemma, i.e. the choice between three alternatives. Following Rodrick’s geoeconomic trilemma, I formulate the biopolitical trilemma as a choice in which the set of interests of only two of the three agencies can be unambiguously taken into account. In our case, we are talking about the government of a sovereign state,a sovereign citizen and the population as a population of people within state borders.

In this model, the interests of the state are focused on achieving the absolute sovereignty, the interests of the population are centered on the biological and microeconomic survival, while the interests of the citizen are directed at preserving its political and socio-economic rights, which make it a sovereign equal to the state.

Given these interests, the future of political systems will fluctuate between three sets of political choices.

- illiberal sovereigntism (autocracy) appears as a compromise between the interests of the state and the population. Here, the sovereignty of the ruling group coincides with the survival of the population.

- Depopulating democracy is the result of a compromise between the government and the citizen, when the constitutional balance of the rights of the citizen and the government limit the ability to respond quickly and effectively to epidemiological threats. This, in turn, contributes to the relentless depopulation of certain countries and the creation of a demographic vacuum, which sooner or later would be filled by migrants from overpopulated regions (Africa and Southeast Asia).

- Finally, decentralized anarchy is the result of a compromise between the citizen and the population interests. Given that most current states are quite deficient, certain social groups, communities and individuals take responsibility for their own lives and disregard the ineffective government. This option mobilizes individual and big and small groups to experiment with stateless forms of politics, including anarchist projects, sub- and trans-national de facto state projects etc. This active political creativity would bring chaos, conflicts and new political formations, only a small part of which is likely to provide equality, freedom and security to its citizens in the first half of the XXI century.

Assuming this model is correct, it partly supports Mr. Pasenyuk’s assumptions and conclusions. The pandemic and related crises do encourage political mobilization and creativity. Part of this creativity can certainly contribute to the emergence of free political regimes and systems. However, in addition to this option, there are many others, including sovereigntist and/or anarchic.

The European nations, including Ukrainians, can make any choice they want but one: they cannot refuse to make that choice. Biopolitical challenges force us to act — indifferently, intelligently or emotionally, but necessarily in an active and creative way. Populist imitation is not possible in this situation. And an attempt to reject choosing will lead to the end of the political community’s existence.

* During the quarantine, the opposition (where it existed) refused to criticize governments. With the end of quarantine, competition between political groups has resumed. However, the resume of competition is much more affective and emotional.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations