The central bank’s profit is often politicized, although the regulator’s main task is to maintain price and macro-financial stability. Profit is merely a consequence of the policy aimed at achieving this stability. Moreover, usually economic growth leads to losses for the central bank, while an economic crisis increases its profit. In the article, we examine in detail what constitutes the profit of the central bank and what factors influence it.

In any country, the profit of central banks occasionally attracts close attention of politicians and society. However, the attention to the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) profits is consistently high. The reduction in transfers to the budget is perceived as nearly a verdict to the effectiveness of monetary policy. And for some reason, any increase in this transfer is always interpreted as concealed emission.

Public interest in central banks’ profits and the transfer of a portion of these profits to budgets is justified. At least from the accountability perspective, central banks must explain the intricate interplay between their mandate, the policies executed to fulfill it, the policy implementation tools, and their financial consequences. Due to specialized knowledge and specific nuances of central bank operations, a typical problem of informational asymmetry arises. Central banks and other stakeholders operate with different amounts of information and perceive it differently. On the one hand, this creates conditions for constructing complex corporate governance models for central banks, within which auditing and approval of financial reporting extend beyond exclusively executive bodies. On the other hand, it generates certain tensions regarding the fiscal impact of regulators’ profits.

Macroeconomics, political economy, and financial results of central banks

The profit of central banks is not the purpose of their activities. This principle is so well-established that it has become a standard legal norm in many countries. At the same time, the existence of such regulations indicates the need for formal protection of regulators from political pressure. The independence of central banks today is inconceivable without a financial component, within which decisions to fulfill the mandate should not rely on considerations of generating a profit and transferring a portion of it to the budget. However, this is only in theory. In practice for many central banks, even in developed countries where the rule of law prevails, the fiscal aspect of central bank profit is often politicized.

In addition to purely fiscal considerations, the question of central bank profits has several politico-economic dimensions.

First, losses experienced by central banks can be indicative of inadequate management. Despite being an extremely rare occurrence, politicians want to make sure that lower-than-expected financial outcomes are not a result of poor central bank management.

Second, profits and losses of central banks have a cyclical component. Typically, profit increases after crisis episodes or cyclical downturns in the macroeconomic conditions. Expanding central bank balance sheets in one period leads to increased profits in the next one. Decreases in profits or even losses often accompany situations when the economy is on an upswing and does not require an increase in the central bank’s balance sheet. However, the political cycle differs from the economic cycle. Fiscal revenues concern certain political actors at specific political moments regardless of the cyclical behavior of the regulators’ financial indicators.

Furthermore, the profits and losses of central banks are generated through significant operations related to ensuring financial stability. For developed countries this implies asset purchasing while for emerging markets – accumulation of FX reserves. In the latter case, the increase in FX reserves is not just a structural component of adaptation to shocks in the global economy, dollarization, and weaknesses in the domestic financial market. Reserves play a crucial role in maintaining price and financial stability. However, the benefits of expanding assets and the losses from holding a significant portfolio of assets may not align with the electoral cycle. In other words, there will always be an issue whereas lower transfers from central banks coincide with the tenure of certain political actors, while the benefits of central banks’ ability to ensure macro-financial stability are reaped when other political actors are in charge.

Central banks’ financial results can be used as a weapon for political attacks on their policies if these policies, although implemented within their mandates, do not align with specific vested interests. These interest groups can be commodities barons aiming for a low exchange rate, oligarchs whose businesses heavily rely on insider loans, owners of online casinos, etc. In any case, the lines of financial reporting can serve as effective media tools to discredit socially optimal policies.

The cyclical mismatch between macro-financial stability and the cost which society pays for it in the form of central bank financial outcomes becomes a natural politico-economic issue. This, in turn, gives rise to another problem: the price of stability is invisible, while the financial results of central banks are clearly traceable in reports and budget transfers. The reluctance to link them leads to politicizing the financial dimensions of regulators’ activities. Perception of achieved and maintained stability as something given can play a cruel joke on them. Even the best standards of accountability and transparency for central banks are not always capable of neutralizing the effects of politico-economic dissatisfaction with financial results. This is especially true if such dissatisfaction results in political pressure on central banks and their independence.

Structural changes in central bank activities and the issue of financial results

The transition of central banks to practices aimed at controlling short-term interest rate fluctuations has led to the emergence of operational designs that require interest expenses. Two main design options exist: the interest rate corridor and the “floor system.” In the first case, instant access operations ensure that banks have the ability to place excess liquidity at an interest rate reduced by a certain number of basis points from the policy rate. In the second case, central banks accrue interest on bank account balances.

These operational designs have proven effective in implementing inflation-targeting regimes. Furthermore, they (especially the floor system) are compatible with quantitative easing programs as they ensure control over the lower bound of money market interest rates under substantial liquidity surplus. However, at the same time, they necessarily increase central banks’ interest expenses for.

While interest rates were low, this did not pose much of a problem. The situation changed when, in response to the surge in inflation after 2021, most monetary authorities were forced to raise interest rates. This automatically led to an increase in interest expenses. Additionally, a problem of re-evaluating the value of large bond portfolios in balance sheets emerged. When rates rise, the value of bonds issued at lower rates decreases. This also significantly impacted financial results. Several leading central banks, including the ECB, have already announced negative financial results for 2022.

However, it is important to consider that fiscal shortfalls resulting from negative financial outcomes are incomparable to the fiscal revenues governments gained from the stimuli created by central banks to rescue economies from the trap of prolonged post-crisis recession. Creating liquidity excesses post-crisis helped to swiftly renew financial stability. It also prevented significant and largely invisible fiscal losses.

Countries with emerging markets face a somewhat different dilemma. This is most vividly observed in the case of Central and Eastern Europe. The respective central banks accumulated substantial foreign exchange reserves in order to prevent a significant fundamental strengthening of exchange rates in response to increased economic productivity and foreign direct investment inflows. Foreign exchange reserves became a source of strong structural pressure toward expanding liquidity surplus, later compounded by asset purchase operations. Similar issues are characteristic of several Asian countries as well as commodity exporters.

In any case FX reserves create a liquidity surplus. Adapting the operational design to this surplus requires significant interest expenses from the central bank. The revaluation of foreign currency assets due to exchange rate strengthening becomes an additional factor influencing financial outcomes. Notably, there are many examples of employing long-term liquidity withdrawal instruments where negative financial results are practically chronic. As prominent examples consider the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, and Indonesia, whose central banks at different points in time issued their own debt instruments with maturities ranging from 3 months to a year.

Ukraine: the price of stability

The NBU has been implementing monetary policy in an environment of structural liquidity surplus for quite some time. The main driver of this surplus is the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves. During the COVID-19 crisis period, long-term refinancing entered the stage (it no longer plays a role today) and during the war – emissionary budget support. External aid inflows to cover the budget deficit also support foreign exchange reserves, contributing to liquidity growth.

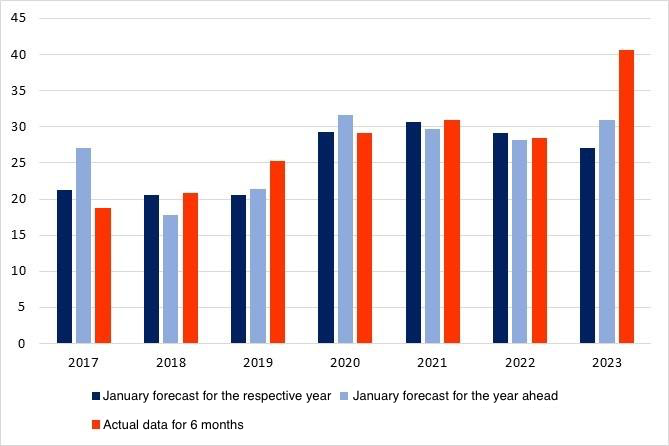

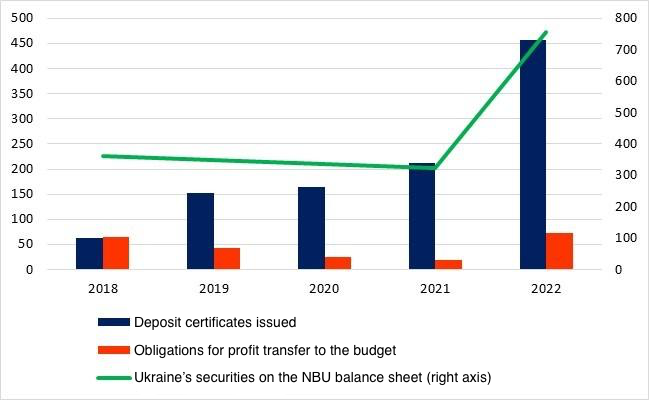

In recent years, the NBU has often had to revise downward its forecast for transferring profits to the budget. This adjustment was often grounded on the disparity between forecasted and actual foreign exchange reserves. Figure 1 demonstrates that the largest discrepancies between predicted and actual levels of FX reserves occurred in 2019 and 2023. Notably, in 2019, the volume of issued deposit certificates increased significantly (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Gross foreign reserves: forecasted and actual, billion USD

Source: NBU data

However, the sum of profit transfers to the budget is not as strictly determined by liquidity withdrawal operations as one might expect, as is particularly evident from the indicators for 2022 (Figure 2). Indeed, apart from net interest income, this amount is influenced by asset revaluation, exchange rates, and the formation of general and other reserves. In other words, the dynamics of the NBU’s fiscal contribution are influenced by multiple factors. But the larger the NBU’s balance sheet becomes, the less predictable the amount of transfers to the budget will be.

Figure 2. Deposit certificates and NBU operations with the government, billion UAH

Source: NBU data

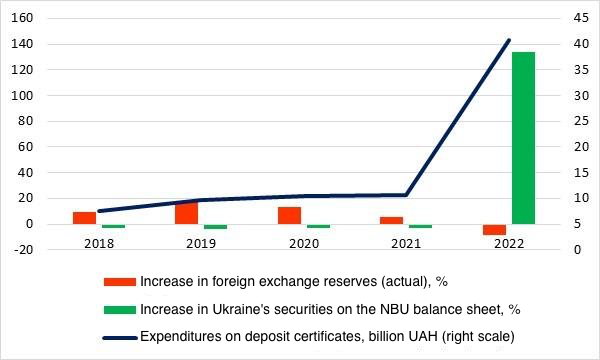

NBU’s budgetary obligations are not highly correlated with the volume of liquidity withdrawal operations. However, the expenses associated with these operations clearly follow the volume of liquidity creation. Figure 3 demonstrates that the increase in expenses for deposit certificates is closely related to the growth of foreign exchange reserves (2019) and the increase in domestic government bonds on the NBU balance sheet (2022).

Figure 3. Sources of liquidity creation and expenditures on deposit certificates

Source: NBU data

Therefore, the NBU interest expenses on instant access operations (overnight loans or deposits) result from liquidity creation processes. However, these processes are not uniform. Accumulation of reserves reflects the need to maintain macro-financial stability, whereas the emission for purchasing domestic government bonds was an emergency measure aimed at stabilizing budget expenditures at the shock moment of the first year of the war.

Thus, NBU financial results merely reflect its contribution to maintaining price and financial stability. Without preventing upward pressure on the exchange rate, the GDP trajectory could have been worse; without a certain level of foreign exchange reserves, it would have been more challenging to overcome the consequences of the COVID and war shocks; and without the emission during the first year of the war, the budget probably would have collapsed.

Anyway, impulses guided by the pursuit of the best outcome pass through a complex system of interconnections between the NBU’s balance sheet, operational design, and macroeconomic processes (however, such impulses are less visible than the line in the financial statement). And the complication of the operational design and the increased role of mandatory reserves during the implementation of monetary policy reflect the NBU adjustment to the prolonged structural liquidity surplus.

Conclusions

Central banks’ profits are more of a political-economic challenge than a macroeconomic one. Achieving better control over interest rates to maintain macro-financial stability comes at a cost that is often more visible than the stability it yields. Attention must be paid to the problem of effectively aligning instant access operations with inflated balances of monetary regulators.

The NBU profit transferred to the budget depends not only on the volumes of deposit operations but on multiple factors. The expenses on such operations directly relate to liquidity creation processes that conceal complex relations between the NBU balance sheet and its implementation of the mandate for price and financial stability.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations