Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, 16 packages of sanctions were imposed by the EU on Russia between February 2022 and December 2023 (since that time, the EU adopted two more sanctions packages).

These sanctions can be divided into two broad categories. First, general trade restrictions, for example, ban from SWIFT of certain Russian banks. Second – trade restrictions on specific goods, such as equipment or microchips to undermine Russia’s military production. For firms trading with Russia, these sanctions came as an exogenous and unexpected trade shock. How did firms respond to this shock? What has changed for them?

To answer this question, I look at monthly administrative data (2010-2022) of Latvian firms and supplement it with customs and employment data. The data includes firms’ profit, sales volume, volume of trade with Russia, number of employees, wages etc. I also consider what exactly a firm produces or imports from Russia to find out whether firms that produced or imported sanctioned goods suffered more.

Prior to 2022, Russia was in the top-5 Latvia’s trading partners both in terms of exports and imports (for geographical and political reasons). Latvia exports to Russia mainly alcohol, machinery, pharmaceutical products, and plastics, and imports mineral fuels, steel, wood, and fertilizers.

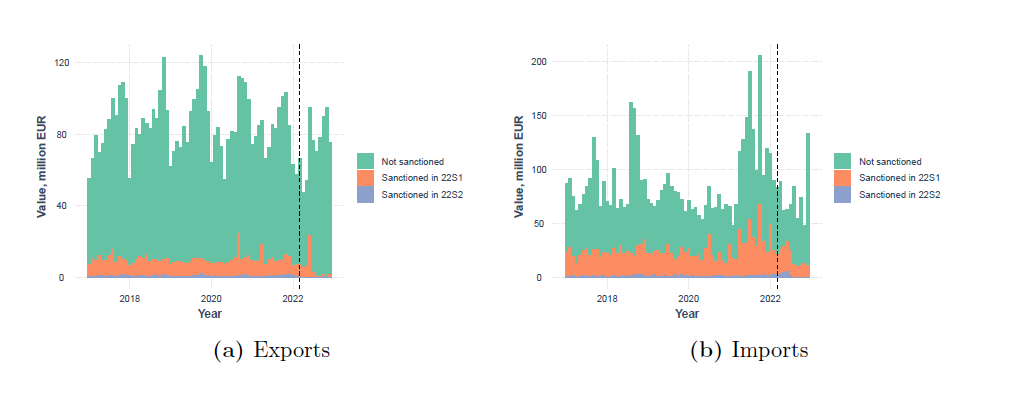

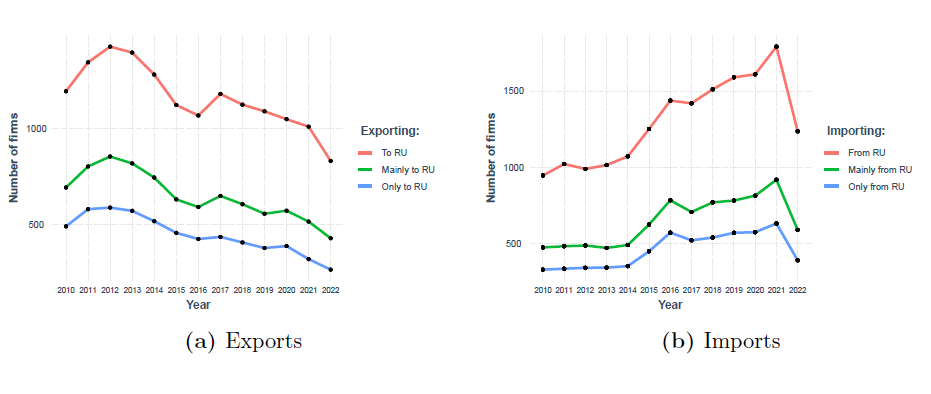

Figures 1 and 2 show aggregate volume of trade between Latvia and Russia and the number of Latvian firms that trade with Russia respectively. Figure 2 shows that the number of firms trading with Russia started to decline well before 2014.

Figure 1. Aggregate trade of Latvia with Russia

Note: the figure shows overall monthly trade with Russia in constant euro, base 2015

Figure 2. Number of Latvian firms trading with Russia, per year

Note: green line indicates the number of firms that have more than 50% of their exports to or imports from Russia, in value

The main research questions are:

- which firms actually experienced a trade shock?

- how to measure this shock at the firm level?

The first question is non-trivial since many firms trading with Russia in a given year do not continue to do so in the following year. A firm exiting the Russian market in 2022 may have stopped trading with partners in Russia, had the full-scale war not started.

Therefore, I used a machine-learning model that studied detailed characteristics and behaviour of individual firms in 2010-2020 to predict which firms would have traded with Russia in 2022 in the absence of the full-scale invasion. I estimated that about 2/3 of firms would have continued trading with Russia in this case (in absolute numbers 617 exporters and 969 importers).

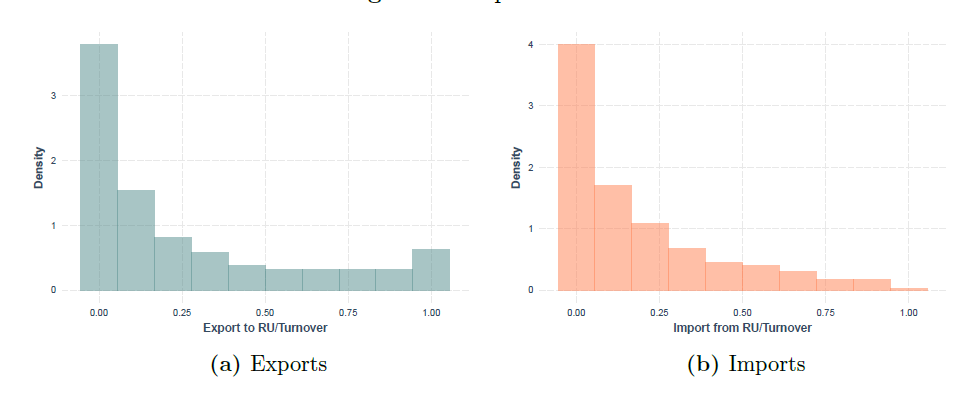

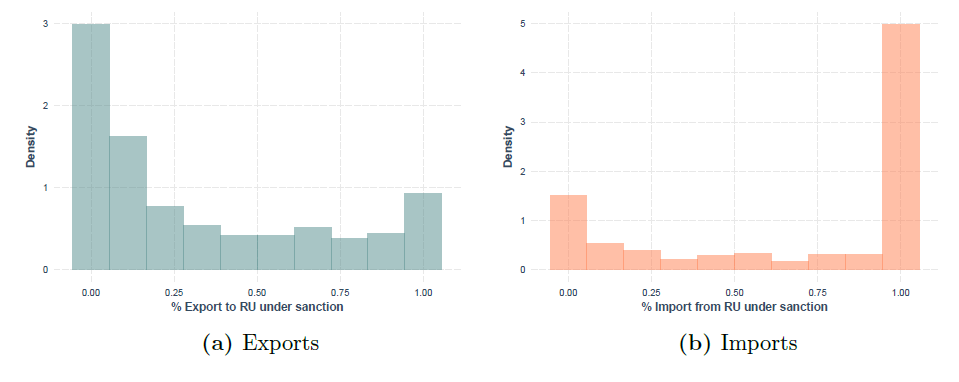

The second issue is figuring out the size of the shock. The literature suggests that we could use the share of sanctioned goods that a firm supplied to Russia in a firm’s turnover. This share can be decomposed into exposure (share of exports to Russia in turnover) and bite (share of sanctioned exports in total exports to Russia). As figure 3 shows, among Latvian firms trading with Russia in 2021, the majority have very little exposure to Russia, i.e. only a small part of their exports (imports) goes to Russia (arrives from Russia). At the same time, Figure 4 shows that a large share of Latvian firms were importing from Russia only goods that subsequently fell under sanctions.

Figure 3. Exposure to Russia (share of exports/imports to Russia in turnover)

Figure 4. “Bite” of trade with Russia (% of exports or imports that fell under sanctions)

I estimate the probability that a firm exits Russia in 2022 due to sanctions. I find that firms with a low exposure to Russia are highly likely to exit the Russian market. On the other hand, the higher the exposure, the lower the probability to exit. The exit rate among the lowest exposed firms is about 65%, whereas it is only 30% for the most exposed firms. However, among stayers, the overall volume of trade with Russia decreased on average by 40%.

Quite expectedly, firms with higher exposure to the Russian market have higher probability to close or lay off staff in 2022 (however, there are very few firms with high probability of shutting down, and the most heavily hit surviving firms would fire only about 10% of the staff). This staff layoff started quite early – already in May/June 2022. Firms with high exposure to Russia also experienced a decline in turnover and profitability. However, this result is driven by a small number of firms with a very high exposure to Russia.

Firms that did not shut down after the sanctions shock decreased their trade volume if they were highly exposed to Russia, while exporters that had low volume of trade with Russia actually increased their exports.

I also found out that the probability to start exporting to CIS countries for firms that used to be highly exposed to Russia increased dramatically in 2022, suggesting sanction circumvention.

Our findings suggest that, in the short run, sanctions do very little damage to firms of countries that apply sanctions to Russia. Only a small number of highly exposed firms significantly suffer from this trade shock. For the large part, firms’ reaction is primarily driven by the mere exposure to Russia rather than the sanctions on specific goods, which nevertheless likely act as a scarecrow. At the same time, firms that used to be highly exposed to Russia are more likely to start trading with CIS countries, which is often used for sanctions evasion.

The full version of this paper can be found via the link.

This research paper was presented at the 9th NBU research conference. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Latvijas Banka.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations