The parliamentary elections are only a few days away, and the election silence will start in several hours. While most journalists, politicians and sociologists are busy analyzing the pre-election ratings, we decided to dig deeper and ask ourselves: what do we really know about Ukrainian electorate?

The question itself is complex and cannot be fully covered in a single blog post. Sociological research tends to focus on socio-demographic characteristics: age, gender, location. However, very little is known about other things Ukrainian electorate cares about. We plan to answer this question with a series of articles.

This article aims to refute three popular myths about Ukrainian voters. Though these myths differ from each other a lot, they do have a common trait — putting the blame on others, people who differ from ‘us’. We will discuss blaming other voters («the other ones»), social media (not the media we use), and civil society («they participate, but do it wrong!»).

Refuting these myths is important because they distort Ukrainians’ perception of one another, putting a wrench into solving complex collective problems.

Disclaimer: In March 2019, before the first round of the presidential elections, VoxUkraine along with the International Renaissance Foundation conducted a representative survey of Ukrainians. We interviewed 1,200 respondents and analyzed their answers using the Political compass.

Myth #1. Other voters

This myth is quite popular in Ukrainian social media. Ukrainians tend to despise fellow citizens who support other political parties. A group often thinks it is the only one supporting Ukraine’s economic growth (important reforms or free market), while other candidates’ supporters drag the country in the wrong direction. Populism is one of the main insults thrown at others.

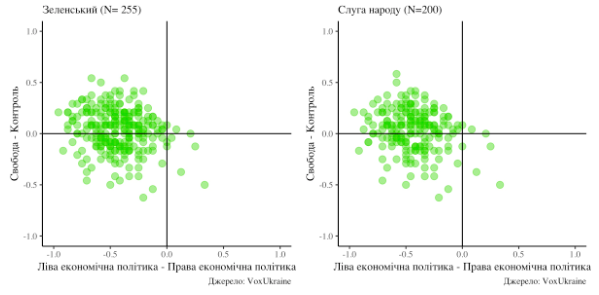

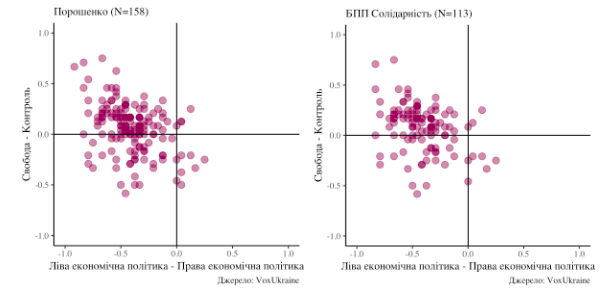

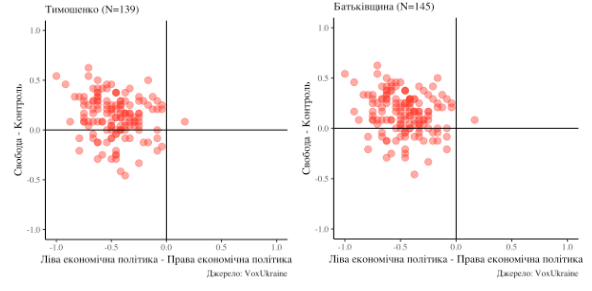

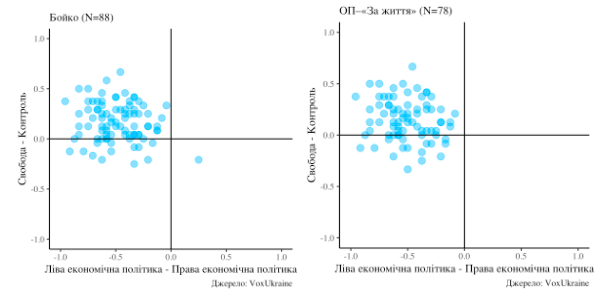

However, our Political compass disproves this notion. In reality, all the Ukrainians who supported the main presidential candidates, as well as parties (as of March 2019) fell into the same section of the political compass.

Disclaimer: Political compass is a result of answering 24 questions. Half of the questions were dedicated to economy — whether it should be free or controlled by the state. The other half concerned the government control of people’s rights and freedoms. As a result, most of the respondents ended up in the upper-left section of the compass. Meaning they often agreed that both economy and the people’s rights should be controlled by the state.

Most of the respondents, regardless of their political choice, ended up in the upper-left section of the compass. What does this section mean? The answer is neither easy nor unambiguous. People can have different reasons for supporting governmental control and human rights limitations. What we want to stress with our analysis is: Ukrainian voters have much more in common than they think.

The questions we marked as a «leftist economic agenda» are often used by Ukrainians in order to call other people populists. And if our readers equal leftist economic agenda to populism, then we will have to admit that all the voters (the supporters of Zelenskiy, Poroshenko, Boyko and Tymoshenko) are populists.

Graph 1. Respondents who said they want to vote for Zelenskiy and the Servant of the People party (before the first round of presidential elections, March 2019).

Graph 2. Respondents who said they want to vote for Poroshenko and BPP Solidarity (before the first round of presidential elections, March 2019).

Disclaimer: Since the survey took place in March 2019, we didn’t ask about the European Solidarity. This analysis does not reflect its current rating. The goal of this analysis is to show that different parties’ electorate (regardless of the parties’ names at the moment) shows similarities on the political compass.

Graph 3. Respondents who said they want to vote for Tymoshenko and VO Batkivshchyna (before the first round of presidential elections, March 2019).

Graph 4. Respondents who said they want to vote for Boyko and OP Za Zhyttia (Boyko, Rabynovych) (before the first round of presidential elections, March 2019).

Myth #2. Other social media

Both traditional and new (social) media are the important tools for political mobilization. They influence people’s mood, their tastes, views and behavior. Some of Ukrainian experts support the idea best expressed by Dmytro Kuleba: «Zelenskiy’s victory is a victory of Instagram over Facebook».

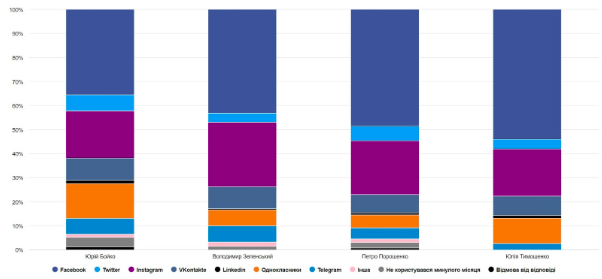

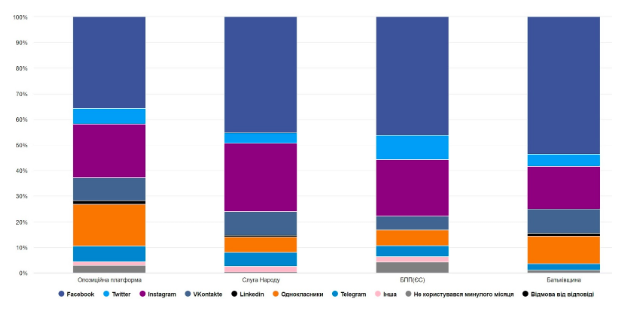

However, our data (graphs 5&6) show that people who supported Zelenskiy and the Servant of the people used Facebook more often, with Instagram taking the second place (meaning the amount or respondents who said which social media they used during the last month). The same applies to the other parties’ supporters.

Fun fact: Odnoklassniki users were the most visible not only among Yuriy Boyko supporters, but among Yulia Tymoshenko ones as well. And even though Telegram wasn’t very popular with Ukrainian electorate, Petro Poroshenko and Yuriy Boyko electorate used it more often than that of Volodymyr Zelenskiy.

The social media usage structure is more complex than it seems on the first sight. Zelenskiy’s voters did use Instagram, but the data show no obvious advantage which would allow us to talk about the fundamental differences between voters.

Graph 5. Answer to the question «Which social media did you use in last month?» and the presidential elections (1,200 respondents, March 2019).

Graph 6. Answer to the question «Which social media did you use in last month?» and voting for the parties (1,200 respondents, March 2019).

Myth #3. «Wrong» civil society

Being an active citizen able to protect their own rights and the rights of others who can ally with other people, seek the common ground, solve complex problems collectively is very important for the electorate. Measuring civil activity and involvement is a hard task. There are a lot of factors which often depend on the context of the situation. Sociology often measures civil involvement as a part of social capital. To put it simply, in theory lack of capital means that people have a limited circle, don’t trust others and are unable to unite for a common goal. Our questionnaire had several social capital measurements — protest activity (did you participate in Euromaidan), the amount of useful connections (core network) and trust for the anonymous other (general social trust).

Electorate of all the main political movements turned out very similar on these metrics. Core network for each group consists of 4-6 people, and general social trust is around 4-5 out of 10.

Different politicians’ supporters were divided only by the question about the Euromaidan: 75% of Poroshenko supporters said they didn’t participate, for other groups the result was 88-94%. We can’t say that supporters of Zelenskiy, Boyko or Tymoshenko differ from each other in this regard.

Table 1. Social capital indicators (1,200 respondents, March 2019)

| Average amount of useful connections* | Average trust to an anonymous other on the scale from 0 to 10 | Part of the electorate not participating in Euromaydan, % | |

| Volodymyr Zelenskiy | 4.7 | 4.8 | 87.8 |

| Petro Poroshenko | 5.3 | 4.8 | 75.3 |

| Yulia Tymoshenkо | 4.4 | 5.1 | 93.5 |

| Yuriy Boyko | 5.5 | 4.6 | 94.3 |

| Servant of the People | 4.8 | 4.9 | 87 |

| OP | 4.8 | 4.5 | 96.2 |

| BPP (ES) | 5.1 | 4.8 | 77 |

| Batkivschyna | 4.6 | 5.2 | 92.4 |

*The questionnaire used the methodology of a nominal generator: «Most people discuss important issues with others. Who did you discuss the most important issues with in the last six months?»

Disclaimer: 75% non-participants does not automatically mean other 25% participated in Euromaidan. The remaining 25% also include those who answered «hard to say», people who helped the protesters bringing food, or participated in the protests in other cities or villages.

In general (excluding a bigger difference concerning the participation in Euromaidan) we didn’t see a glaring difference in social capital of electorate of the main political parties.

Conclusions

Both citizens and experts sometimes fall into the grip of myths and misconceptions about our society. These myths tend to upraise before the elections. We analyzed three of these myths. Despite their differences, they have one thing in common: (1) other parties’ supporters are populists (2) other parties’ supporters use the wrong social media and (3) other parties’ supporters have no social capital. Our data find no confirmation for these myth. On the contrary, they show a lot of similarities among electorate of different parties.

Our analysis has its limitations, of course. There are other ways of measuring one’s social capital or populism, and situation can change with time. However, we have shown the data which disprove these myths.

Blaming others is often based on limited knowledge of one’s own society. We hope new data and their analysis will shed some light on who Ukrainians really are in order to help solve difficult collective problems during the new political season.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations