In 2023, we published two articles on Slavic studies in leading US universities, showing that their course offerings were severely skewed towards Russia both quantitatively (i.e., many more courses on Russia are offered than on other countries) and qualitatively (i.e., rather than taking an objective point of view, they provide a Russian perspective on the subject). In this article, we consider the latest data to see whether things have changed.

Disclaimer. By looking at the selected universities, we do not suggest that the situation in other institutions is better or worse. We suggest that Slavic studies need to be critically revised everywhere. First, the share of content devoted to countries other than Russia should be increased. Second, the remaining Russia-focused content should present a balanced perspective rather than Russian narratives.

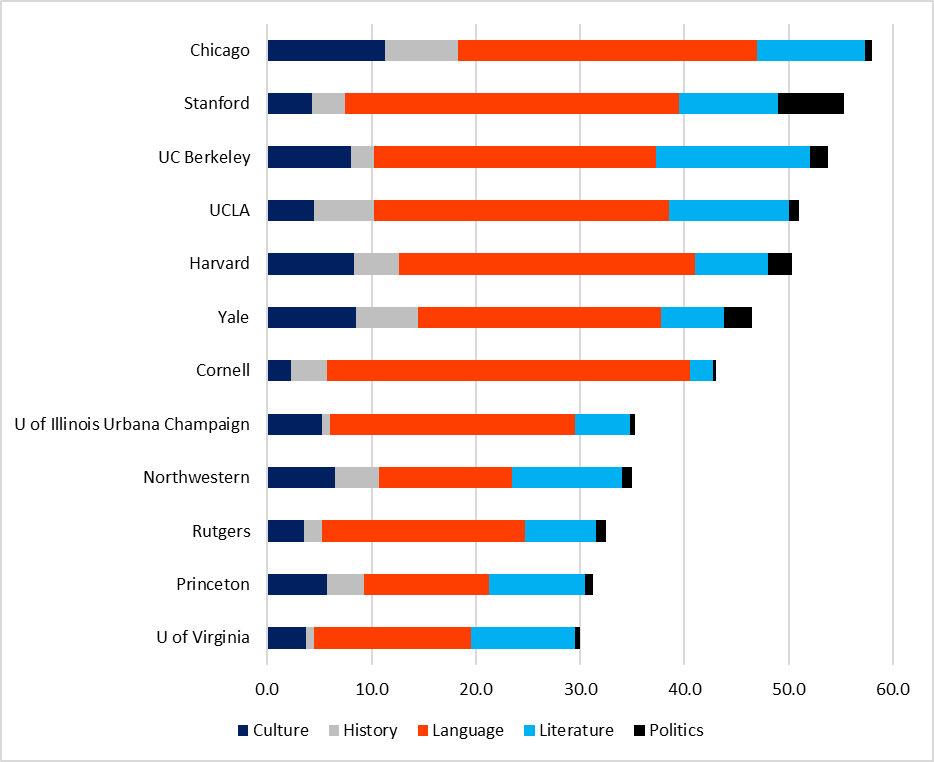

We examine courses offered by the same sample of top US universities over four academic years: 2021/22, 2022/23, 2023/24, 2024/25 (the details of the data are described in the previous article). Figure 1 shows that most courses offered by Slavic departments are language courses (although someone studying a language will inevitably acquaint themselves with samples of literature and culture from that country or countries). The number of courses – between 12 and 25 courses per semester – does not vary much from year to year.

Figure 1. Average annual number of courses offered by Slavic departments of selected universities, by discipline

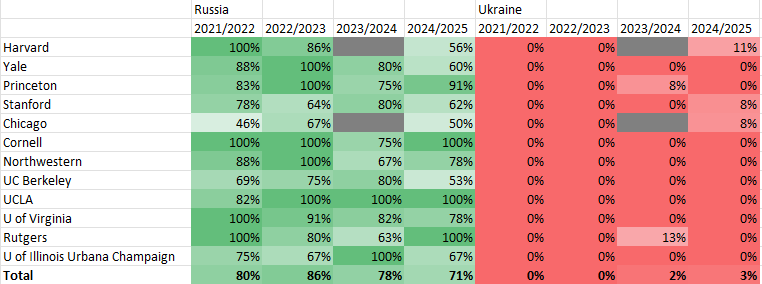

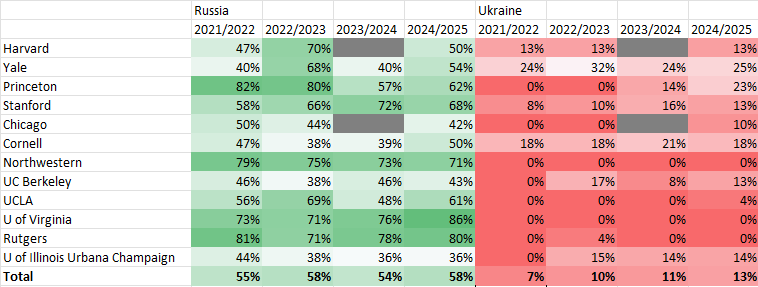

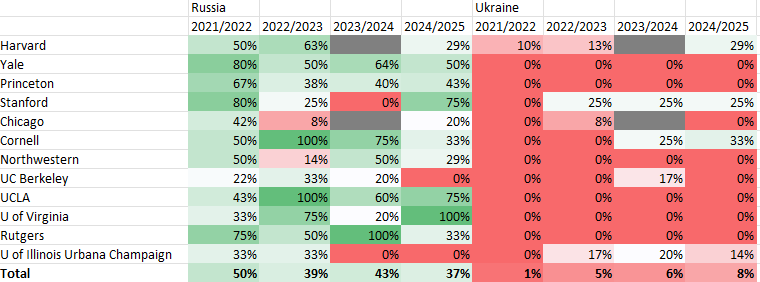

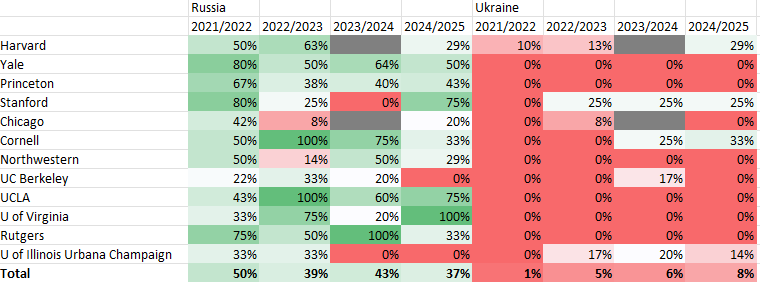

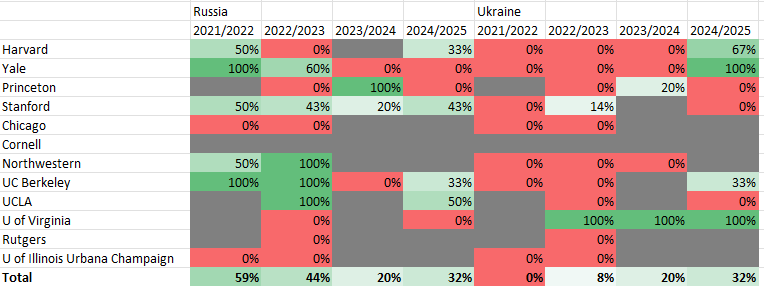

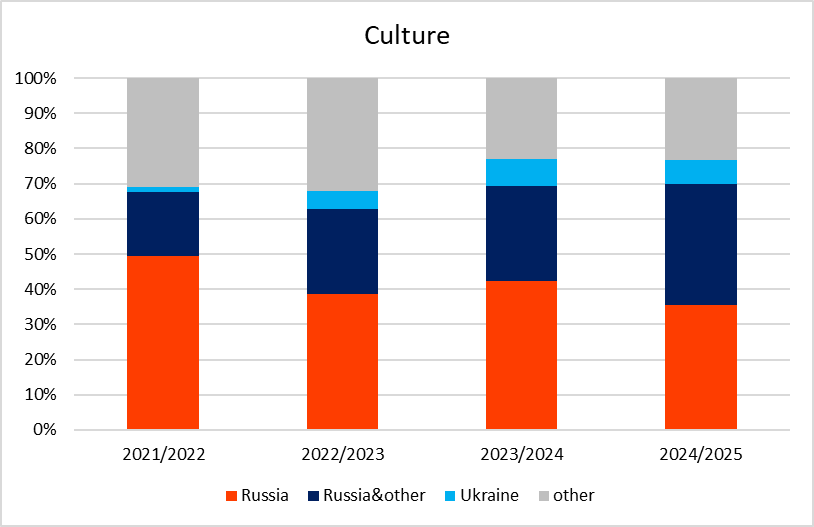

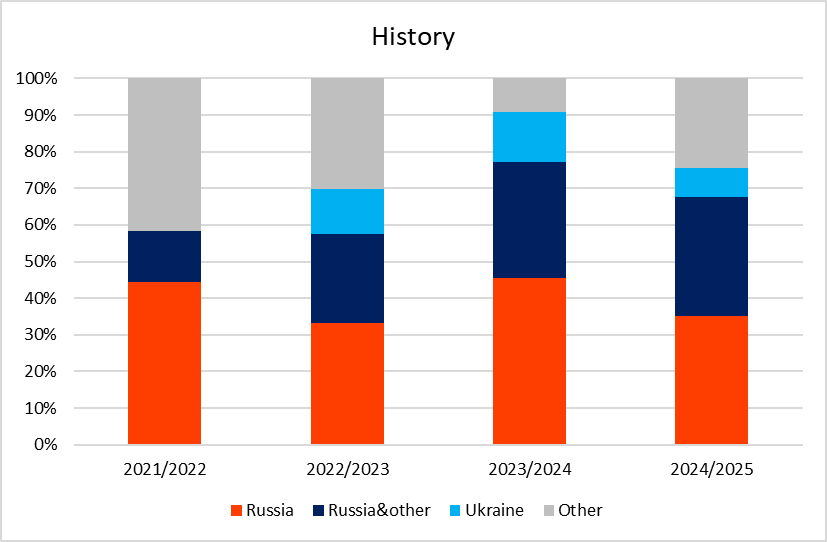

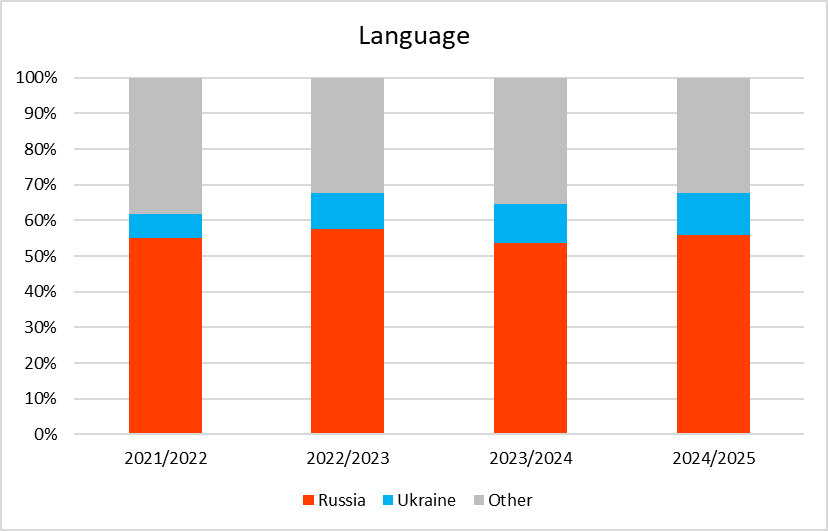

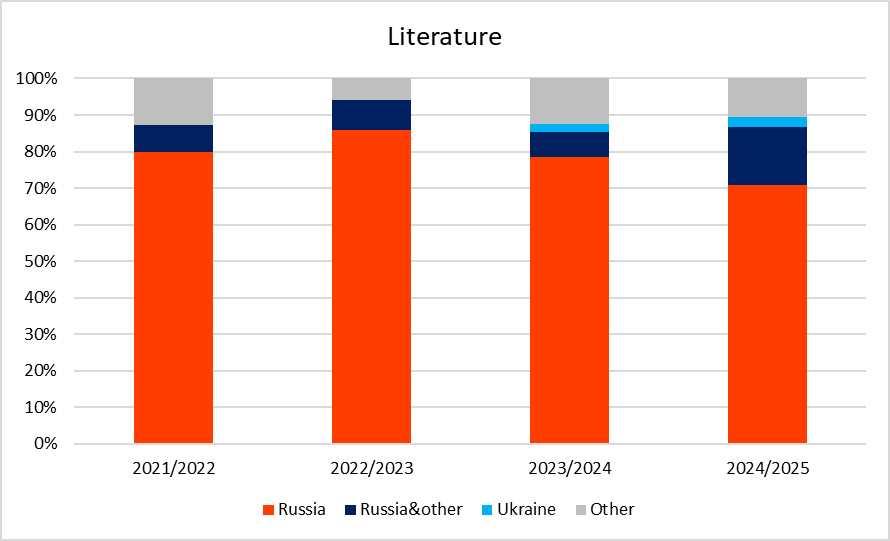

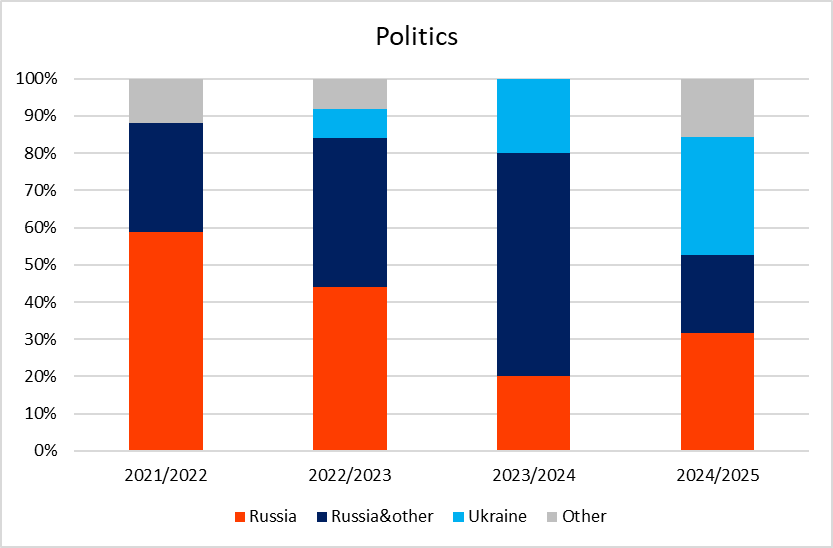

Figures 2A-2E show that these courses, especially literature, have been severely skewed towards Russia. After the start of the full-scale war the situation somewhat improved but not much.

Figure 2A. Share of “Russian” and “Ukrainian” courses in literature

Figure 2B. Share of “Russian” and “Ukrainian” courses in language

Figure 2C. Share of “Russian” and “Ukrainian” courses in culture

Figure 2D. Share of “Russian” and “Ukrainian” courses in history

Figure 2E. Share of “Russian” and “Ukrainian” courses in politics

Note: grey cells mean that either no courses in a certain discipline were offered in a given year or that there is no publicly available data on these courses

As we see from figures 2A-2E, there has been some increase in the share of Ukrainian language and literature courses (although Russia-focused courses remain dominant), the introduction of a few courses on Ukrainian culture in some universities and a spike in Ukrainian history courses followed by a decline. The “politics” courses are few in number, so the rise of Ukrainian courses to 100% usually means that only one course was introduced.

Looking at the description of these courses, we see sharply contrasting narratives. For example, a course called “The Ukraine crisis: East and West” is described as follows: “The Ukraine Crisis has brought relations between the West and Russia to their lowest level in a quarter century. Join UVA faculty member Yuri Urbanovich to discuss the origins, developments and significance of the battle for Ukraine in light of recent political actions.” Calling Russia’s aggression against Ukraine a “Ukraine crisis” and talking about “the battle for Ukraine” deprive Ukraine of sovereignty and make it an object of the “relations between West and Russia,” which is one of the Russian propaganda narratives. A similar language of “conflict in Ukraine” (as if Russia has no relation to it) is used by a Rutgers course on the war.

In contrast, the Yale “War in Ukraine” course “examines in detail why Russia decided in February 2022 to begin a “special military operation” that turned out to be nothing less than a full-fledged war against Ukraine.” Another good example is the UC Berkeley course on Russia titled “Stolen Lands: Indigenous Pasts, Settler Presents, Decolonial Futures,” which takes a decolonization approach in discussing century-long modus operandi of the Russian Empire.

More universities should take an objective approach to Russia that recognizes two basic facts. First, there is no “both sides” or “Ukraine crisis.” Russia is the aggressor, and Ukraine is the victim fighting for survival. Second, as a land empire, Russia has been leading genocidal wars (including the current one on Ukraine) for centuries — this is how it gained its vast territory.

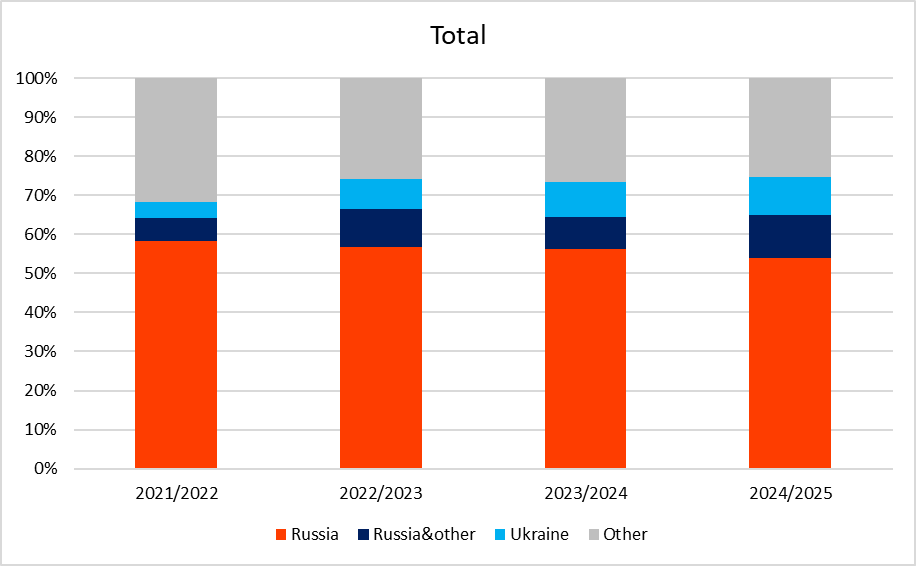

Figure 3 takes a broader view on the composition of courses offered by Slavic departments. Courses that are either focused on Russia (orange) or include Russia (dark blue) constitute well above a half of the total number of courses offered. The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine did not significantly change the composition of these courses (noticeable change in the distribution of “politics” courses is explained by the small number of these courses, where adding or subtracting one course makes a significant difference).

In literature the situation is especially grim. It leaves the impression that Slavic literature essentially equals Russian literature, which is certainly not true. Apart from their dominance, several conceptual problems exist with Russian literature courses. First, their appropriation of Ukrainian medieval literature up to the 18th century (Russia does not have its own baroque literature, let alone earlier texts). Second, their appropriation of Ukrainian writers. For example, studying Gogol not as a Russian writer but as a Ukrainian who suppressed his identity to succeed in the Russian empire would not only pay tribute to the truth but also add a lot to the understanding of his texts.

Third, the courses focus almost exclusively on “Tolstoevsky,” i.e. 19th century novels. These novels describe some ideal Russia or a ‘mysterious Russian soul’ that has never existed. Therefore, they have been extensively used by Russian state propaganda to conceal the true nature of Russian society. Modern Russian literature, even “anti-Putin” authors, is full of propaganda too but since it is aimed at the internal audience, it much more openly describes people of other countries as inferior and/or hostile to Russians (Tolstoevskyies do that too, but in a less direct way). Thus, if the aim is to educate US students about Russia rather than brainwash them into Russia-verstehers, they should read modern Russian literature, e.g. written in the last 30 years.

The texts of Soviet/Russian dissidents should be also read via the decolonization lense: many of them, even those who emigrated to Europe or the US, preserved the imperial thinking, which postulates that Russian people are superior to other nations, and other peoples living in Russian empire do not exist (in this respect they are very similar to modern so-called “Russian liberals“). For example, Solzhenitsyn in his essay “How should we organize Russia?” suggests that Ukraine and Belarus should completely merge with Russia as “one people,” and Brodsky wrote a hateful and racist poem “On independence of Ukraine.”

Figure 3. “Regional” distribution of courses over time

Note: “Russia&other” category includes geographic and time categories related to Russia, e.g. Eastern Europe & Russia, Ukraine & Russia, Soviet Union, post-Soviet countries, etc. This category does not exist in Language courses since languages are clearly attributed to single countries, while culture or literature courses can include several countries.

Many history courses continue to repeat Russian myths. The most common is the inclusion of the medieval state Rus’ (a direct ancestor of modern Ukraine) into Russian history. This historical myth is one of “justifications” for the current Russia’s war on Ukraine (e.g., Putin described it to Tucker Carlson), so it is especially strange that Western universities keep spreading this myth. In reality, kings of Rus’ founded a few forts in what is now Volodymyr and Moscow regions of Russia, but in the 13th century that territory and a large part of Rus’ was conquered by the Mongol empire. Rus’ repelled Mongols in the mid-14th century, while Moscovia emerged from the remnants of the Golden Horde a century later. Since the early 16th century, Moscovia has pursued what it calls the “unification of the Russian state.” In reality, this was a series of genocidal wars that continues today.

The first Moscovian genocide (the term “Russia” was not applied to Moscovia until 18th century) was the killing and deportation of over 90% of the population of the Novgorod Republic by Ivan the Terrible in 1569-1570. Capture of the lands of this Slavic republic, along with later occupation of Ukrainian, Lithuanian and Polish lands, is the foundation of another Russian myth that “early East Slavic” is the same as “Old Russian”. As Czech writer Karel Havlicek wittily noted in 1844, “The Russians like to label everything Russian as Slavic, so that later they can label everything Slavic as Russian.” Unfortunately, some Slavic departments do the same. Some even repeat the Russian lie that “Ukraine” means “borderland” (in reality, “Ukraine” means “country” in the same way as “land” means “country” in “England“, “Netherlands” etc.).

Another common false narrative is equating “Soviet” with “Russian.” While the USSR was indeed a form of Russian empire, peoples living there, including Ukrainians, Georgians, Uzbeks and many others, never considered themselves “Russian,” despite huge Russification efforts. That’s why Soviet leadership after Stalin (unsuccessfully) tried to create an artificial identity of a “homo sovieticus.”

Since 1991, Russification policy in Russia has been much more successful. However, many people still remember who they are and identify themselves as Erzya, Kalmyks, Buryats, Tatars etc. To erase their national identities, modern Russian state not only suppresses their languages and culture but also sends disproportionately large numbers of these people to the frontlines where they are killed (for example, 3.5 times more Bashkirs, 3 times more Tatars and twice more Buryats were killed in the war than representatives of Moscow). Thus, it is fundamentally wrong to talk about a “Russian national identity” since it does not exist. The correct approach would be discussing people facing a choice between acquiescing to the Russian empire vs sticking to one’s national identity (again, remember Gogol as an example).

We are pleased by the fact that some Slavic departments have started to change their perspective on Russian studies. For example, in 2025 Stanford offered a course called “Russian novel decolonized” (its description suggests that the course provides a decolonized view on the ‘classic’ Russian novels). The University of Chicago has a “Russia through its wars” course discussing the culture of nations that have suffered from Russian aggression, and Rutgers’ “Language and Power Behind the Iron Curtain” course takes a view on the “role of language in imperialism and decolonization throughout Central and Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Siberia.” We very much hope that students of this and similar courses will learn that if people in some region speak Russian, one should study the underlying reasons for this rather than suggest that these regions should belong to Russia.

In short, the good news is that Slavic studies have started to move away from Russia-centric coverage. The bad news is that, after more than 11 years of Russia’s barbaric war on Ukraine, progress is quite limited. Clearly, universities should provide more resources and a decisive push to reform their Slavic studies programs so that they can deliver to their students a more accurate portrayal of the Slavic world.

Authors are very grateful to Berkeley student Quinn Vasfiye Mai Shioda for her help with data collection

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations