International monetary and financial system is very complex because we have interconnected and in many cases opaque dynamically-evolving financial markets; it is complex because we expect policy-makers to do many things. But if we would like to get to a more efficient system, it seems that there are a number of elements that we should be aiming for. First of all, flexible exchange rates seem to be essential – Ukraine experience has illustrated that. So are the best possible domestic macroprudential policies which we would need in any case just to address the fact that monetary policy can’t simultaneously deal with targeting inflation and preserving financial stability.

The framework I want to use for this set of remarks is the one of two very contradictory views about monetary policy in an open economy. One of these views is that an open economy, provided the exchange rate is flexible, is qualitatively no different from a closed economy. I would cite here the paper of Mike Woodford (2007) that shows that a central bank with an inflation target can meet that target provided the exchange rate is flexible regardless of what shocks are coming from outside of the economy. The other view which is diametrically opposed (it was put forward by Helen Rey in a number of papers which are rather well known now – on dilemma versus trilemma) which is that small open economies have no monetary autonomy regardless of the exchange rate regime because of the effects of financial inflows driven by global financial cycle linked mostly to monetary or financial sector developments in bigger countries, notably the United States.

I take a position between these two extreme views because they both have some validity.

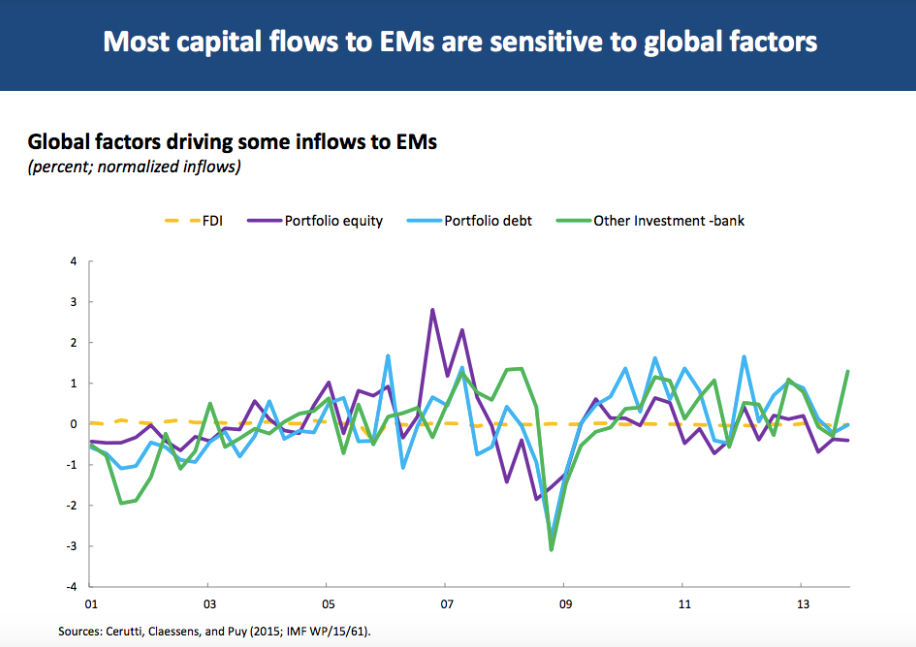

There is no doubt that there is a global financial cycle. If you just look at global capital flows into emerging markets as one of many possible measures, you can see a common cycle in many of the components (Figure 1). This chart breaks up investment flows into the emerging markets (EM) into components (FDI, portfolio equity, portfolio debt, and other investment flows, which is mostly banking flows). What you can see is that FDI is incredibly stable. The other flows do show a lot of co-movement.

Figure 1. Investment inflows into EM

These are not actually the flows themselves but estimated portions of flows which are explained by the global cycle (Cerutti, Claessens and Puy, 2015).

So there is a financial cycle – but what does it tell us about the prudency of monetary policy and the trilemma of monetary policy?

The trilemma of monetary policy in the open economy states that the following three desirable characteristics are not all mutually compatible:

- Fixed exchange rate

- Free cross-border capital movements

- Monetary autonomy

Example. If you fix the exchange rate and allow free capital movements, then monetary policy has to be devoted to fixing the exchange rate, it cannot simultaneously target domestic prices or domestic output or some other thing. Conversely, even if you have capital mobility, if you allow exchange rate to float, then monetary policy can target something else – and this is the main message of Woodford (2007) paper I mentioned above.

In the days of Bretton-Woods system US indeed occupied a very singular position in the world economy because with n currencies in the world you only had n-1 exchange rates. Countries outside the US pegged their exchange rates [to gold] but there was a degree of freedom left, which was the freedom of the US to use monetary policy. Technically, there was a link between US currency and the price of gold but for a variety of reasons that was quite loose and it loosened over time. So the US indeed was exceptional. At the end of 1960s and even much earlier than that people like Milton Friedman and Harry Johnson argued for the regime of floating exchange rates on the grounds that floating exchange rates would create symmetry – every country would be able to use its monetary policy to target its inflation rate. In their view, this would be a much more preferable system than the one in which the US inflation rate was determining the inflation rate abroad, for example, in countries like Germany or Switzerland, which were very unhappy with the results.

When exchange rates started floating in the early 1970s, we learned that life was much more complicated than Friedman and Johnson had advertised. Charles Kindelberger wrote the paper “The Case for Fixed Exchange Rates, 1969” (published in 1970), the most famous quote from which is:

«Along with one more instrument – the exchange rate – you have one more target – the exchange rate.»

And it was even before we started talking about financial stability concerns that we now talk about all the time.

So where are we in this debate about monetary autonomy? How should we think about it? I would argue that neither of the quotes I provided at the beginning – the first one saying that with floating exchange rates monetary autonomy is complete, the second one saying that even with floating exchange rates there is no monetary autonomy – is right. The first of these quotations is basically about the world with one target and one instrument. So if you want to target inflation – you have monetary policy – and that’s the end of this very simple story. But it’s not a world in which real central banks live.

To my view, the second story about the world in which there is no monetary autonomy is also an exaggeration. (Of course I am simplifying here to make a general point on how we should think about monetary policy).

I think a great framework is the one that Stanley Fisher set out in his paper “Myths of Monetary Policy” (2010). He said that many central bankers talk about having enough instruments to hit their targets. And it turns out that for a typical problem that central bankers face there never going to be enough instruments, there will always be more targets than instruments. And so it’s not very useful to think about hitting all your targets – because you just won’t. Then how should you think about it? Think about a loss function where you try to get close to these targets and where you basically weigh against each other the tradeoffs of being distant from all of your targets.

In this framework, the value of the central banker’s loss function in equilibrium will depend on the tradeoffs in the economy that a policy maker faces – for example, on the short-term Phillips curve (tradeoff between inflation and employment).

How does economic openness matter in this setting? Economic openness provides gains from trade but it can also worsen some of these policy tradeoffs. So even if you are optimally exercising whatever monetary autonomy you have you are likely not to end up as close as you would like to be to your bliss point with respect to the various desired outcomes (inflation, unemployment or other). There is no doubt within this framework that with a fixed exchange rate as an additional constraint on the monetary policy you would never be better off, and I would argue that you would actually be worse off.

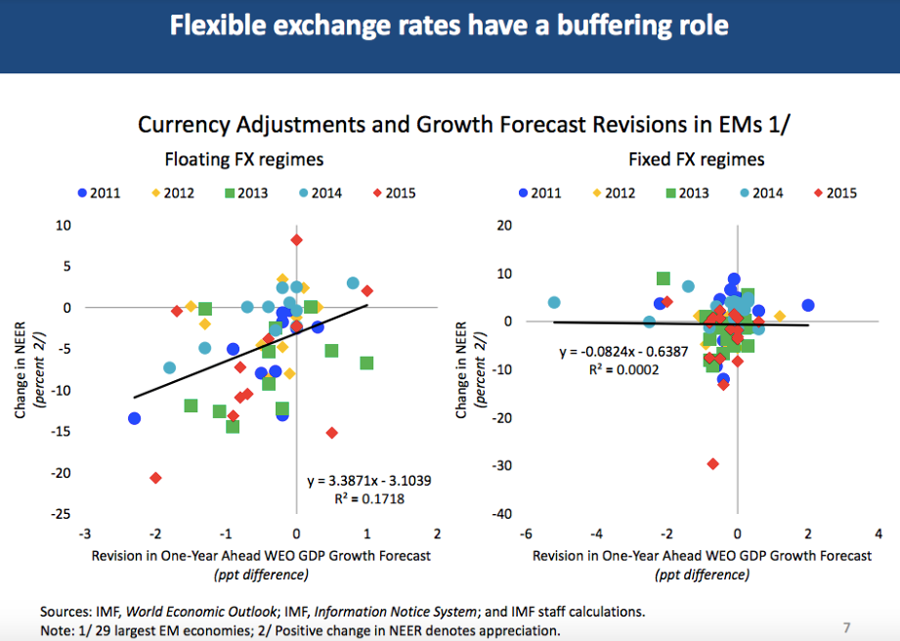

To make that case, one has to argue that there is a benefit from floating exchange rates – some payoffs that we don’t have under peg. Obviously, you avoid the possibility of currency crisis, which can be quite damaging. But it’s also true that floating exchange rates play a buffering role that is fairly evident in the data (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Exchange rate regimes and growth

These are world economic outlook data – forecast revisions for real GDP growth (we do these revisions twice a year – in April and October). These are plots of these revisions for 2011-2015 for large emerging market economies against changes in nominal effective exchange rates (NEER). On the left panel there are countries with fairly freely floating exchange rates. On the right panel there are countries with some kind of pegged or heavily managed floating arrangements.

Figure 2 shows that when output surprises on the upside, the currency tends to appreciate, and conversely when it surprises on the downside, it tends to depreciate. This is partially due to the fact that currency movements are driven by aggregate demand, and partially due to reactions of central banks to these output changes. So when people say that exchange rate movements are completely random, and there is no relationship to the economy, think about a picture like this. Of course it’s possible that these relationships are driven by the mechanism under which exchange rate depreciation causes output to fall – this may occasionally be true in crisis situations but this is not for the most part true (as is evident from this picture) over this time period. An exchange rate adjustment can be very useful and I would argue that is has been useful, especially in the recent history. For example, think about commodity exporters whose terms of trade have fallen recently – you’ll see there large depreciations which have had positive impacts in buffering these economies.

Since monetary autonomy is one instrument that we are trying to use to hit many goals, it is useful to evaluate monetary policy in that setting.

Sometimes in a closed economy there is a “divine coincidence” between stabilizing inflation and stabilizing output. That’s not true in all models. Furthermore, the exchange rate itself, as Kindelberger argued, can be a target of policy: countries may have sectoral objectives in terms of promoting an export sector which has high learning-by-doing or productivity externalities; there can be adjustment challenges when exchange rates change rapidly in moving resources between export-oriented and more non-tradable sectors; for countries that have dollarized liabilities there can be balance sheet spillovers. Hence, there may be harsher tradeoffs for the policy maker in terms of allowing exchange rates to change – and this gives rise to the literature on fear of floating for emerging markets – the idea that central banks might be more prone to limit the exchange rate fluctuations. However, this does not remove the fact that there are benefits from the additional degree of freedom from allowing exchange rate to change – perhaps not as much as under completely free floating.

What is the global financial cycle idea about?

I think it usefully highlights some non-traditional mechanisms of transmission in the modern world of highly integrated financial markets. A traditional monetary transmission mechanism can be viewed as hinging on interest rate parity condition such as

it = itUS + Etet+1 – et + ρt

The basic idea here is that, for example, if the US cuts interest rates, an EM country will receive capital inflows that will tend to make its currency appreciate. If for some reason this country doesn’t want it to appreciate and intervenes, its central bank will buy foreign exchange and thus increase its monetary base. Absent sterilization, that will feed through to financial intermediaries who may be not well equipped to deal with a very large volume of intermediation, and that might cause financial stability problems down the road.

This is a standard story (see Calvo, Leiderman and Reinchart, 1996 on the wave of capital inflows to EM in the mid-1990s).

In recent years, we have started to focus on a number of non-standard transmission channels which may make the situation even more challenging. For example, think about cross-border bank lending that relaxes quantitative credit constraints and may undermine domestic credit controls. In terms of monetary control, if there are capital inflows, if more, say, dollar credit becomes available from abroad to an EM country whose currency is not the dollar, one can argue that when you borrow in dollars and swap into domestic currency, with covered interest parity you’ll still be paying the interest rate that the central bank sets, so the central bank has monetary control. But covered interest rate parity may not hold exactly depending on what the opportunities for hedging are. And many economies have experienced carry trades when borrowers chose not to hedge – this has been destructive in many cases.

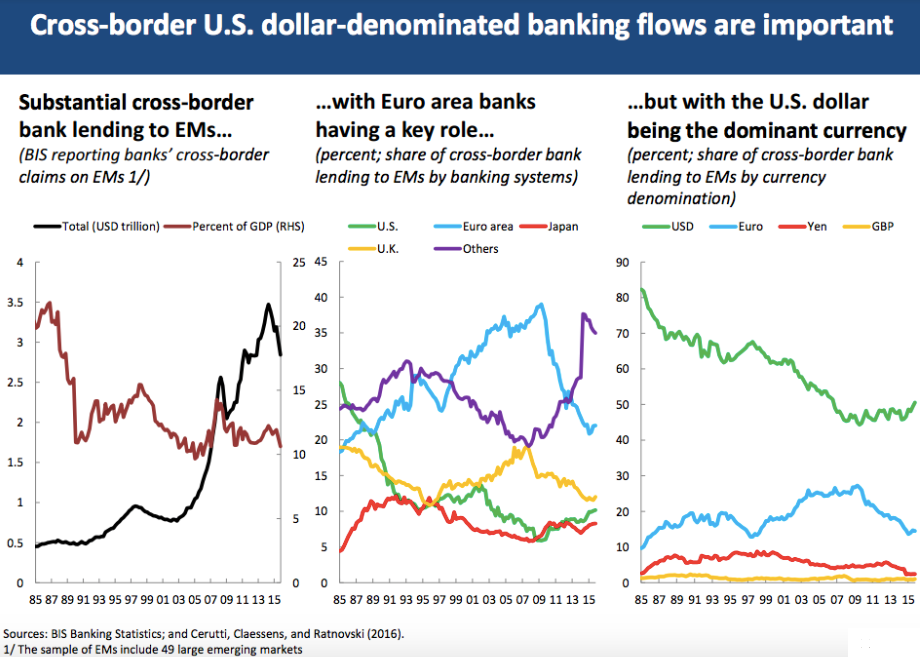

We notice in the data that direct long-term interest arbitrage across currencies appears to be a very powerful mechanism, which could limit monetary autonomy to some degree. US dollar now plays a special role. It is not the role it played under the Bretton-Woods system but there is a lot of financial intermediation in dollars in the global economy among the non-US actors, and this gives USD credit conditions a special role. At the same time, domestic currency bond markets have developed in a number of emerging markets – and this is on the whole useful because it reduces the problem of original sin of having to borrow in foreign currencies. These markets can be thin, they may be susceptible to events in the US or other large bond markets but nevertheless there is a lot of change since 1990s. Figure 3 illustrates the role of the dollar.

Figure 3. USD is extensively used outside the US for transactions

There is a substantial cross-border bank lending to the emerging markets, and the key role is actually played by euro area banks, but the dollar is the dominant currency in these transactions (the right graph). So what the FED does will have impact on a large range of banks’ balance sheets not just for US banks but also for emerging markets banks that are financed in dollars. So it’s a rather complex world out there, and the global financial cycle partly driven by US monetary policy to my mind is a real factor for countries to contend with.

If there are shocks coming from global asset markets, exchange rates in general are not going to cleanly offset those shocks. The Friedman-Johnson shock, the one they worried about most was higher inflation abroad than what you desire at home. So if US is inflating and Germany doesn’t want to inflate at the same rate, Germany should float its exchange rate and appreciate the Deutsche mark to offset that.

Think about a portfolio shift towards EM assets. Even if a central bank lets the exchange rate appreciate without intervening, if there is domestic borrowing in dollars – that is going to strengthen domestic balance sheets and loosen domestic credit conditions. So there you have immediately one possible transmission mechanism because although dollarization may be lower now, it has not totally disappeared. Even if the current account position doesn’t change (and thus capital inflows don’t change and there is no intervention) and all the adjustment is on the private portion of the capital account, there can be offsetting changes in gross positions which could have implications for economic activity and financial stability and for general resilience. Finally, portfolio shifts can feed through to other domestic variables such as corporate borrowing spreads which tend to fall when there is high global liquidity or what we sometimes call risk-on conditions. If you look at corporate Korean spreads, these fell very sharply during the liquidity boom in 2000s.

In some way these are all hypotheses and some of them are substantiated by various partial equilibrium models but I have to admit there is not a lot of general equilibrium modeling of these phenomena and this is one area where we need some more research.

Let me show you some evidence that is suggestive if not definitive of how transmission of monetary policy from large to small economies actually has worked.

I will show you some regression results (Shambaugh, Obstfeld-Taylor-Shambaugh, Klein-Shambaugh)

Δijt = α + βΔibt + γXjt + υjt

In this equation, if we had no monetary policy independence, we would expect β=1.

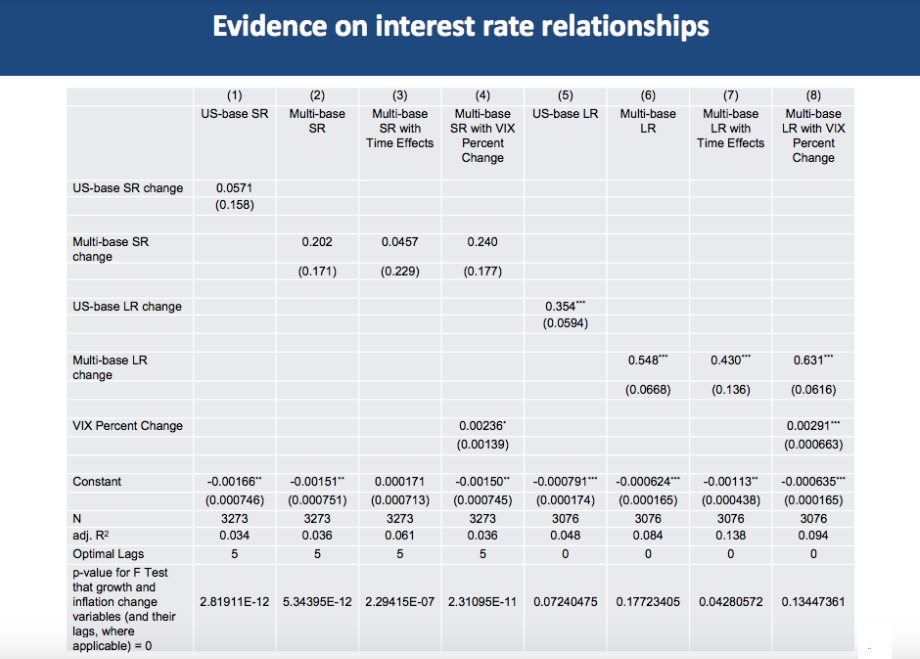

To estimate it, we regress a change in a country’s interest rate (Δijt) on the change in the base country rate (Δibt) and some domestic variables using a large panel of countries (Table 1).

Table 1. Regression results

First, we defined US as the base country because US is usually identified as the driver of global financial conditions. When we do this regression for short-term rate changes (very short-term, such as one-month Treasury bill rates), the coefficient is 0.05 (first column) – so it’s quite far from one. We broke our sample into emerging markets and advanced markets, and for emerging markets the number is actually smaller, even though there has been much discussion about the powerlessness of EM central banks. But you might think that there are common drivers of these interest rates. Unfortunately, in the first regression, since we are regressing everything on a global factor – the US interest rate change – we can’t see this. But then we recognize that different countries may peg to different bases (for example, Ukraine might more naturally peg to Euro than to USD) – and indeed in the regressions with different bases the coefficient is higher.

Then, we put in the time effects – because if you have a common time effect you will probably be overestimating the reaction to base rate movements due to a missing variable which is positively correlated with the US interest rate. Putting these time effects in drives the coefficient down to 0.04. The final experiment we do is instead of time effects we put in the VIX – which is often taken as an indicator of the global risk aversion. A rise in VIX is associated with falling US interest rates because US is a safe haven – so this variable is negatively correlated with change in USD interest rate. When we put that in – we actually get a bigger coefficient of 0.42 but still nothing significant on short-term rates.

The last thing we tested – do any domestic variables enter the regression? For short-term rates domestic variables are all highly significant. So, the picture that emerges from looking at the short-term rates is that there is not much correlation in the short term between rates, domestic factors matter, so there seems to be some exercise with monetary independence at the short end of the curve.

You can do all of the same experiments with long-term rates (column 8 of Table 1) – and you see that all of these coefficients are significant. The last coefficient is 0.63, significant at 1% level, so the domestic policy variables tend not to matter, and that’s a pretty high correlation.

Somehow at the long end of the yield curve there is a lot more coherence. And this is the direct long-term arbitrage phenomenon I referred to before. At the short end the exchange rate regime matters – if you break up into pegs and non-pegs by putting in a dummy variable – the correlations are indeed higher for pegs, and you can’t really say that there is no monetary independence.

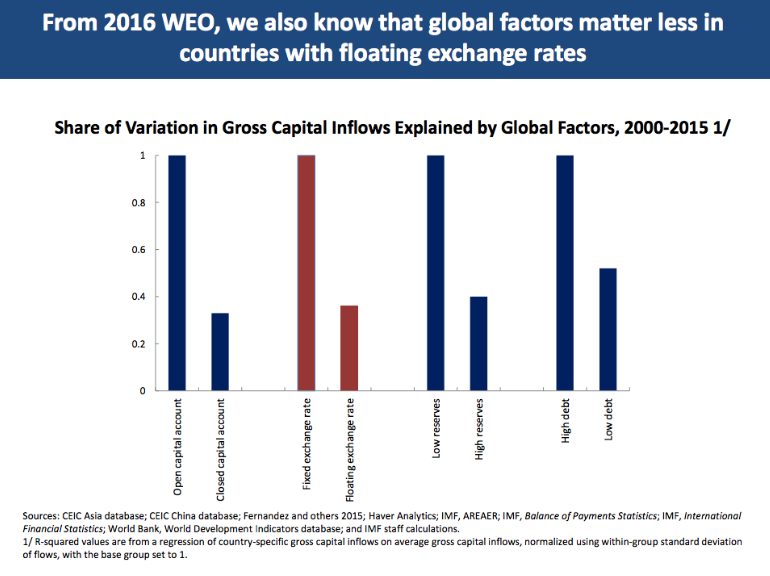

Figure 4. The share of gross capital inflows explained by global factors

Figure 4 shows the share of gross capital flows explained by global factors. For floating exchange rates global factors indeed matter less – this is another metric of the point I made before.

So there is monetary autonomy. But what is the problem with the global financial cycle? What Helen Rey argues is that the global financial cycle is associated with financial stability problems. And what you need to escape those is either macroprudential instruments or – if those cannot be made effective – then capital controls.

This is not a particular problem of the open economy. As I mentioned earlier, even for a closed economy financial stability is an issue. There is a huge debate about the extent to which the monetary policy should be shaded to deal with financial stability issues. But you can’t use your one instrument – monetary policy – and expect to hit exactly your inflation target, your financial stability target and also output target if you have one. So even in the closed economy there are tradeoffs but in an open economy it’s going to be even worse – because it’s inherently harder to do effective macroprudential policies in the open economy. I find it useful to think about this problem in terms of a different trilemma (Shoenmaker, 2013).

The following three are all not mutually compatible:

- Financial stability

- Non-intervention in cross-border capital flows (open capital markets)

- National control over financial supervision and regulation

An extreme version of this which we’ve seen recently has been a Eurozone crisis – where supervisory capacity was delegated to the national level but with fixed exchange rates and with free movement of capital. And the result has been to gather more supervisory power to the center – to the single supervisory mechanism and to the single resolution board. But these problems are not intrinsic to a common currency area. They actually apply more broadly to countries which are linked by international financial relationships but have their own currencies.

Empirical work by Cerutti, Claessens and Levine (2015) indicates how macroprudential measures in open economies induce greater cross-border borrowing to offset them. When one tries to address this – they employ, at least implicitly, some sort of limitation on free movement of capital.

Another sense in which fixed exchange rate is limiting for financial stability is the difficulty of being a lender of last resort when you are simultaneously fixing the exchange rate. We always refer to Bagehot when we talk about lenders of last resort. But reflect that Bagehot was writing in a world where Britain was on the gold standard – so it had a fixed exchange rate. Monetary policy was devoted to that goal. But he also wanted the bank of England to act as a lender of last resort. And the solution to how to avoid what we now call the twin crises – is to lend at very high rates. People say “high rates are about moral hazard”. But they are at least partially about staying on gold because if you have a panic and you raise the interest rate and lend freely to your banks – you’ll stabilize your banks and you’ll also not lose gold. Andrew Thornton who in his 1802 book actually formulated the “lender of last resort” theory well before Bagehot did actually recognized these two conflicting goals of monetary policy. And we saw this tradeoff in the Asian crisis: do you raise interest rates to stabilize the currency and therefore make the situation of your banks worse or do you keep interest rates low but then the currency depreciates making the situation of your banks worse? It is an inescapable tradeoff. But there is no doubt that having the flexible exchange rate – at least when you can get rid of dollarization – will help you a lot as a lender of last resort.

All in all the floating exchange rate seems to be the winning strategy to me and so saying that floating exchange rates don’t matter is a huge exaggeration.

Conclusion

International monetary and financial system is very complex because we have interconnected and in many cases opaque dynamically-evolving financial markets; it is complex because we expect policy-makers to do many things. But if we would like to get to a more efficient system, it seems that there are a number of elements that we should be aiming for.

First of all, flexible exchange rates seem to be essential – Ukraine experience has illustrated that. So are the best possible domestic macroprudential policies which we would need in any case just to address the fact that monetary policy can’t simultaneously deal with targeting inflation and preserving financial stability.

But the financial trilemma indicates that having sound domestic macroprudential policies may not be enough – you may have to supplement them. We try to do that through the international coordination that has evolved since the mid-1970s in the work of the Basel Committee and of the Financial Stability Board. In fact, Basel III contains reciprocity rules that can allow macroprudential policies to be more effective across borders.

Another way to do this is to try to establish domestic regulatory control over large foreign banking operations and organizations which is something the US has been doing – but at the cost of segmenting the synergies some of these organizations may create with their business models. Probably, given national sovereignties, full coordination is not the goal we can attain. Hence, there is a room for capital flow measures, administrative measures, which may at times be needed. To my mind the question being forward is not if but how and when [these measures should be introduced]. For this purpose we do need some rules of the road that would allow us to minimize some of the externalities that can arise when countries resort to capital controls (we need to govern the use of capital controls for attaining competitive advantage over other countries).

The OECD Code of capital account liberalization is being revised again to take account of recent changes in international markets. The IMF has evolved an institutional view on capital flow measures which can be legitimately used in certain situations. Enhanced facilities for international liquidity support are also an obvious need. With all that dollar intermediation it is fortunate that during the crisis FED set up the swap lines, and there is now a network of swap lines for the major central banks but that does not extend to emerging markets. EM have instead accumulated large stock of reserves and while these have served them pretty well including in recent times, gross reserve accumulation can have negative consequences, for example by imparting a deflationary bias to a global economy. Finally, in terms of national balance sheets, I mentioned lower dollarization as being important, also we can see the evolution from debt to equity (as I showed earlier, FDI is very stable, and it’s a preferred method of foreign finance). Equity inflows of a portfolio nature are still preferred to debt inflows which lead to the debt crisis.

The problems of economic management in the open economy are real. They are particularly real for EM, particularly for small EM, but there is a level of interdependence that we have embraced which makes all economies susceptible to global shocks. Even in the US in the mid-2000s Alan Greenspan complained about the conundrum of trying to manage the economy when he found that raising short-term interest rates had a much smaller effect on long-term rates. This is again a symptom of great coherence of long-term rates which I showed to you.

A lecture at the annual research Conference “Transformation of the Central Banking”

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations