If we can’t eliminate them, then what should be done about these cycles? Modern economic theory suggests that governments should use countercyclical policies to smooth these fluctuations.

A standard recipe for the government has two parts. In recessions, the government should run a deficit (more spending, less taxation) to support the economy. In economic booms, the government should save (run a fiscal surplus) to repay debts accumulated in recessions. As a rule, governments are much more sensitive to the first part of this recommendation while trying to avoid the second one. There is always an incentive to stimulate the economy a bit more in order to win some more votes. Of course, increased government spending comes at a cost – higher government debt and thus higher interest payments (but quite often this is already a problem for the next government).

To reign in this urge to spend, many governments introduce fiscal rules. The most famous example of such rules is the 60% cap on the debt-to-GDP ratio and a balanced budget over a business cycle (that is, a government can run a deficit in a recession but it should run a surplus when the economy recovers).

Budget deficit can be financed either by borrowing (internal or external) or by privatization. Some countries finance the deficit by printing money but this would be a very bad choice for Ukraine. To assess whether public debts are sustainable, it is informative to look at primary budget deficit, which is calculated as budget deficit (revenues minus expenditures and net budget loans) less interest payments on government debt. Primary budget deficit shows whether a government spent more than it earned after mandatory payments to debt holders.

To better understand the concept, consider an example. Suppose you need to pay UAH 1000 interest on a bank loan. If you earned UAH 10000 and spent UAH 9000, you run a primary surplus and thus you can easily pay to the bank. If you earned UAH 10000 and spent UAH 11000 (i.e., run a primary deficit of UAH 1000), you must borrow UAH 2000 to not only cover your deficit but also to pay to the bank. Thus, when a government runs a primary budget deficit, its debt rises.

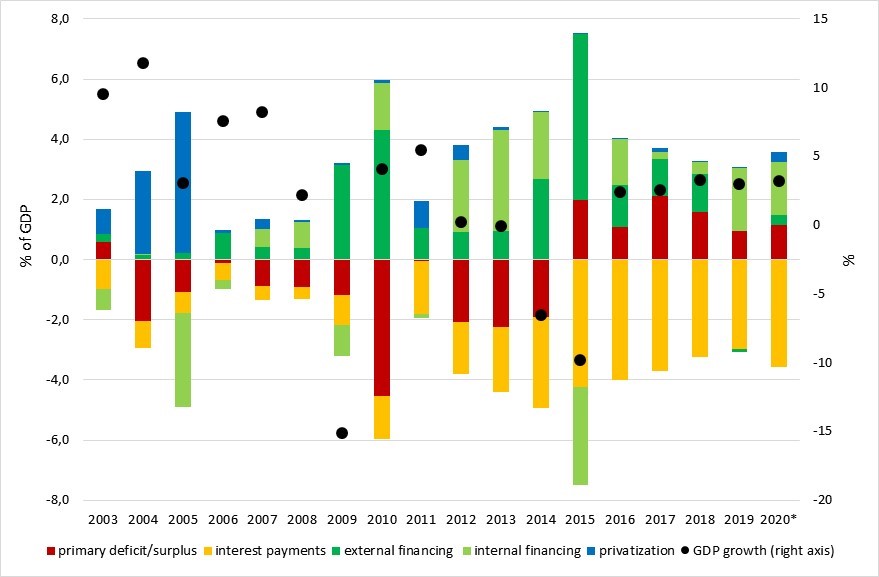

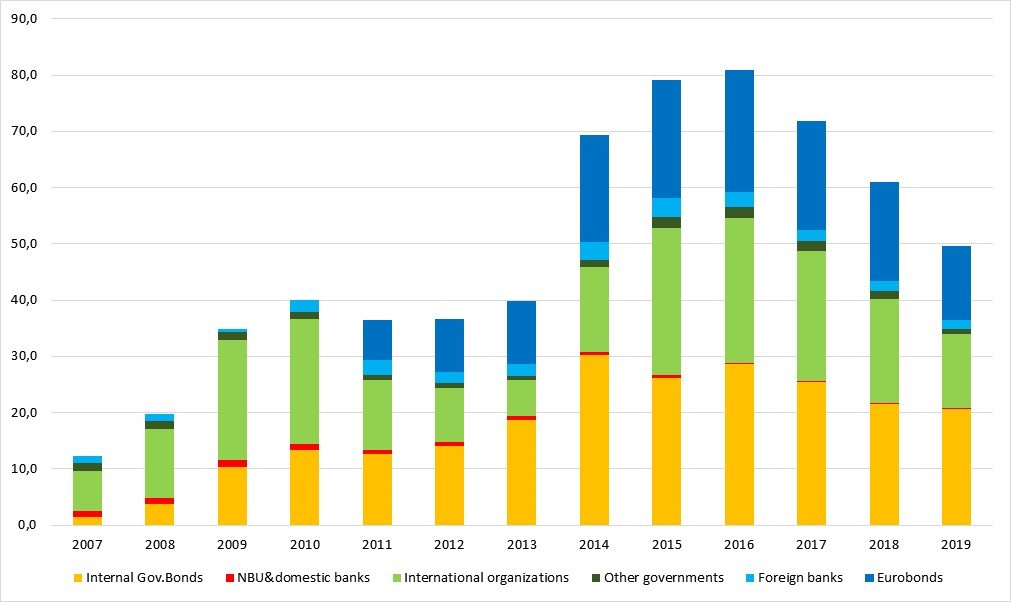

Did Ukraine’s governments adhere to these rules? Figure 1 shows that it was not always the case. Thus, in 2004-2007, and then again in 2012-2013 Ukraine ran a primary deficit when its growth was positive (and in the first period also very high). In 2005, the government debt decreased compared to 2004: very high revenues from privatization of Kryvorizhstal steel mill allowed the government to repay some of its debt. After that, however, the debt started to grow (figure 2). Debt restructuring in 2015 and a prudent fiscal policy largely supported by the IMF program allowed Ukraine to lower its debt-to-GDP ratio in the recent years. At the same time, this figure shows how Ukraine’s government financed domestic companies with the help of foreign borrowing in times of crises: in 2009 this was bailing out of a few banks, in 2015 the government support was provided to banks, deposit guarantee fund, and Naftogaz.

Figure 1. Budget deficit and its financing, 2003-2020

*2020 – as planned in the State Budget law adopted in 2019. Financing includes borrowing and other types of financing (deposits, funds remaining in other budgets or on the Treasury account etc). Since 2008 external financing includes only borrowing. Source: Treasury reports, Law on State Budget-2020

Figure 2. Debt to GDP ratio by holder, 2007-2019, %

Source: Ministry of Finance

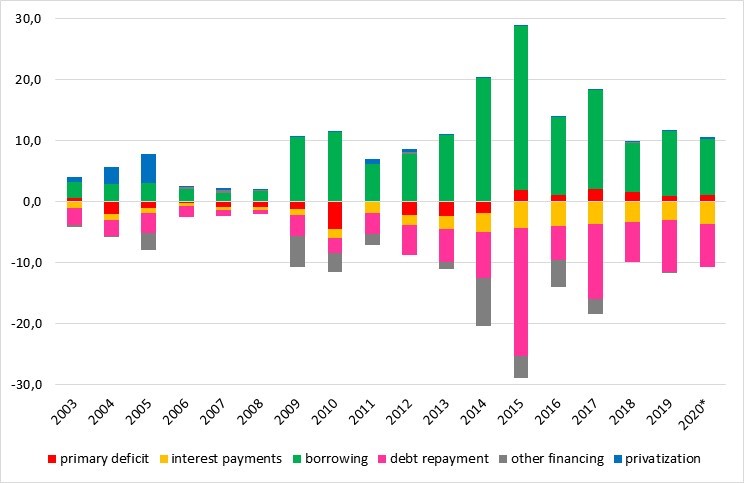

Unlike a household, the government does not have to fully repay its debt – it can replace expiring bonds with new ones and roll over the debt forever. This rollover can happen under two conditions: (1) interest payments don’t get out of control, i.e. government revenues grow faster or in line with interest payments, and (2) there is someone willing to lend money to the government. As Figure 3 shows, every year the Ukrainian government had to repay rather large amounts of debt. At the same time it was able to roll over the debt with the new borrowing.

Figure 3. Primary deficit, debt repayment and servicing, % of GDP, 2003-2020

*As planned in the Law on State Budget adopted in 2019. Source: Ministry of Finance, Treasury reports

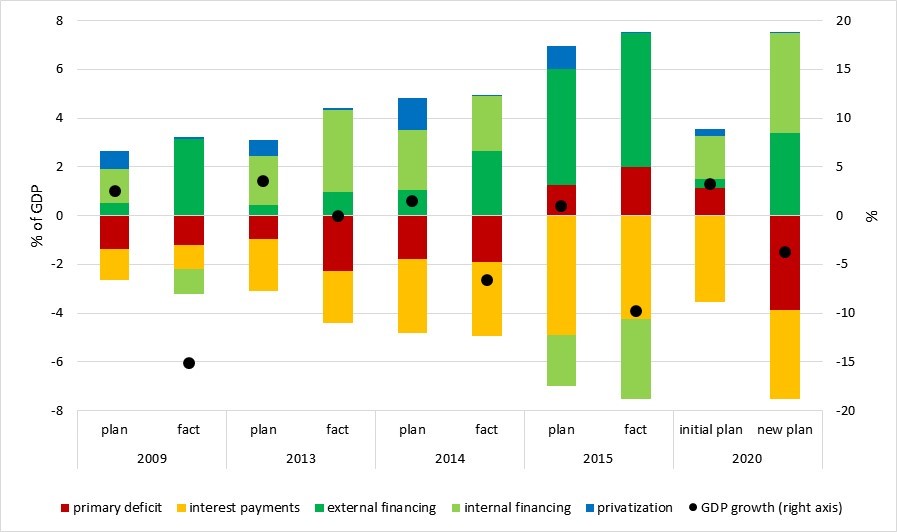

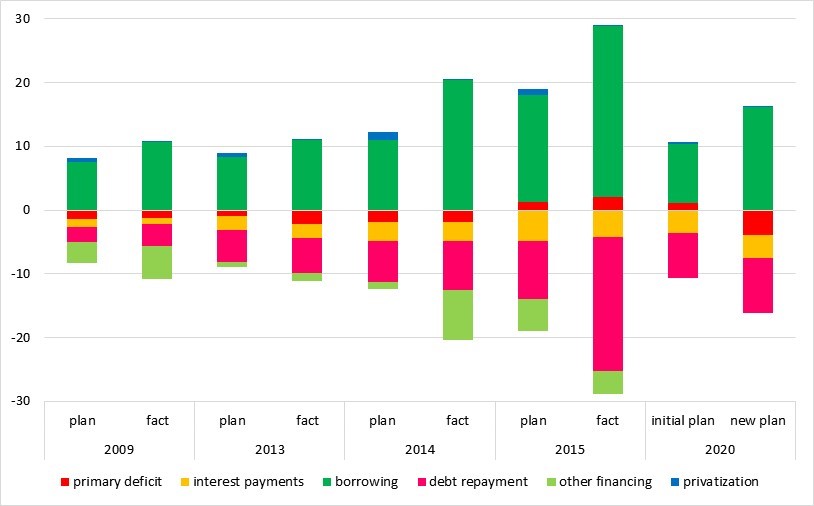

Let’s have a closer look at crises times when due external factors actual growth was very different from forecasts. Figure 4 shows that during the 2009 crisis the government abstained from much spending and even reduced the deficit (by 36% in nominal terms). In 2015 the situation was similar, although restructuring of a part of the debt reduced interest payments. This figure also clearly shows how missing privatization revenues were replaced by external borrowing.

It also illustrates that in 2009 and 2015 the government provided practically no fiscal stimulus, which may have added to the economic downturn. Then, as well as today, Ukraine could borrow only from the IMF and other international institutions. They, however, believed that Ukraine could find a lot of fiscal space by eliminating internal inefficiencies (for example, by reducing corruption in public procurement).

Today, the situation is different. Firstly, reforms implemented during the last few years likely have addressed the major inefficiencies. Secondly, when the economy stops working, the shadow sector also stops and thus cannot act as a cushion during the crisis. Thus today the Ukrainian government can do what a “normal” government would – support people and businesses and invest into healthcare.

Figure 4. Budget deficit and its financing, crisis years

Note: in 2020 initial plan means state budget adopted in 2019, new plan is the amended budget law adopted on April 13th 2020. Source: Treasury reports, Law on State Budget-2020

At the end of 2019, the Ministry of Finance planned to borrow $13.5 billion in 2020 to repay $10.4 billion of government debt and finance the budget deficit of about 2.4% of GDP. The new version of the budget is based on the assumption of -3.7% GDP decline and a respective drop in revenues. It also includes some fiscal stimulus to the economy. It implies almost $22 billion of borrowing to repay the debt and finance a deficit of 7.5% of GDP. Still, as Figure 5 shows, the situation seems better than in 2015 when Ukraine lost part of its territory and nearly 9% of GDP.

Figure 5. Primary deficit, debt repayment and servicing, % of GDP, crisis years

Is this plan feasible? Yes, with the support of the IMF and other partners who will loan money to Ukraine. Can these plans be overly optimistic? Yes, for two reasons. First, the global economic crisis could be deeper than we expect today. Second, the Ukrainian parliament and the president could fail to meet the requirement for an IMF program. Without IMF support, the situation in Ukraine would be catastrophic. Ukraine would not be able to finance the planned spending and would have to run a primary budget surplus in the time when both economic theory and common sense suggest that it should do the opposite (previously we explained that a default and money printing are not feasible options either). This makes the choice very simple: serve the interests of an oligarch who still owes at least $5.5 billion to the Ukrainian people, or create an opportunity for the country to more or less smoothly pass through the crisis.

In summary, the Ukrainian government often lived beyond its means, and the price of lavish, procyclical public spending was deep recessions because the government would not have resources to stimulate a depressed economy. This time is different. Since the Revolution of Dignity, Ukraine has been building fiscal space to help people and businesses in an economic downturn. This is the time to use fiscal firepower to counter the crisis. Our partners (the IMF, the World Bank, the European Commission, etc.) are willing to help Ukraine, but the Ukrainian authorities must do their homework to make it all feasible.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations