The economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a sharp decline in labor market demand and deepened the problems inherent in Ukraine’s typical division of labor. Although more men than women lost their jobs during the hard lockdown in the spring, women were more negatively affected by the crisis. First, the most risky areas in terms of virus infection are medicine, education, household services, retail, etc., which are mostly “female”. Second, the traditional burden on women in housekeeping and childcare has increased significantly.

In particular, the closure of pre-school care facilities and schools has put additional burden on working women or caused forced incapacity for work. Most countries around the world are trying to mitigate the impact of the crisis primarily on families with children: by providing direct remittances, guaranteeing additional paid leave, and helping to reduce the burden of childcare.

Disclaimer. The article is prepared as part of the Kyiv School of Economics project to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the economy of Ukraine with the support of the Embassy of Canada in Ukraine

How much has unemployment risen as a result of the crisis? The official data

The official labor market statistics, namely the ILO’s unemployment rate, are released 2.5 months after the end of the quarter (for example, labor market data for the third quarter of 2020 were published in mid-December). In a crisis, when everything is changing rapidly, it does not allow to quickly assess the state of affairs and form a rapid political response.

In the spring of 2020, there was a great need to understand what was happening in the labor market, researchers were making different estimates, but in fact all of them were in the dark until the end of September, when employment and unemployment statistics for the second quarter of the year were published.

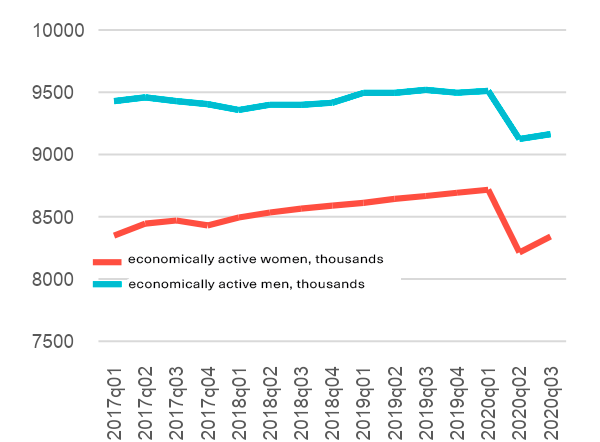

Official data show not only an increase in unemployment in the second quarter of 2020, but also a sharp decline in the number of economically active persons (previous researches also expected this). Under quarantine conditions economically inactive were, for example, the self-employed and entrepreneurs whose activities were limited and who took a waiting position to resume their activities after the restrictions were canceled. They are also people who not only lost their jobs, but also stopped looking for them due to factors such as lack of transport to get there, or problems due to the closure of educational institutions (those who had no one to leave their children with). This also includes the part of seasonal workers who returned to Ukraine in March waiting for the opening of borders with the EU after the lockdown, and therefore did not join the ranks of the unemployed (see also Annex 1).

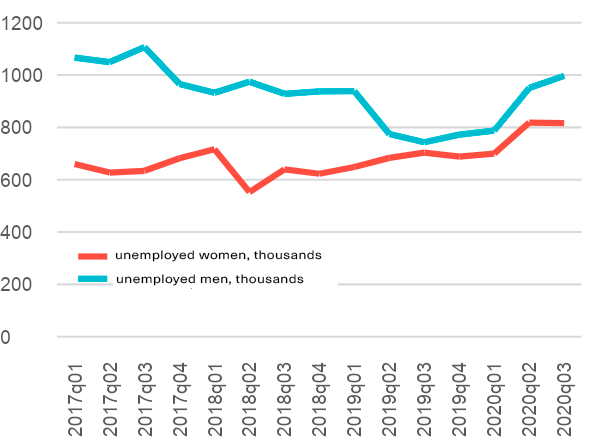

In total, the number of employed ones decreased by 1.2 million people, which is fully in line with our previous estimate. According to the data at the economic level, both men and women have been hit by the situation approximately equally. However, the microdata that we consider below show that economic activity was mixed during the three months of the second quarter.

Figure 1. Number of unemployed women and men, seasonally adjusted indicators

Figure 2. Number of economically active women and men, seasonally adjusted indicators

The real-time unemployment estimates

Besides the official statistics of the State Statistics Service, we use data of eight waves of Gradus opinion polls on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of Ukrainians to quickly study labor market trends (detailed methodology is in Annex 2).

The survey was conducted from late January to mid-May, i.e. covered the pre-quarantine period and the entire period of strict quarantine. We divide respondents into employed, unemployed and economically inactive (see Annex 2 for details). Among the economically inactive we single out:

- self-employed persons who have no income but do not consider themselves as unemployed;

- “others” — those who noted that they are employed in a certain field without having a paid job. They are temporarily out of work, but cannot be classified as economically active because they do not consider themselves as unemployed.

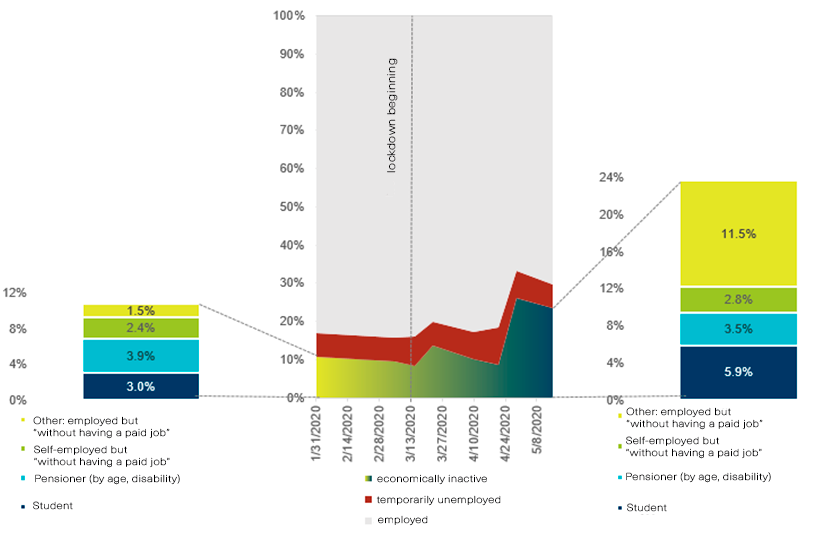

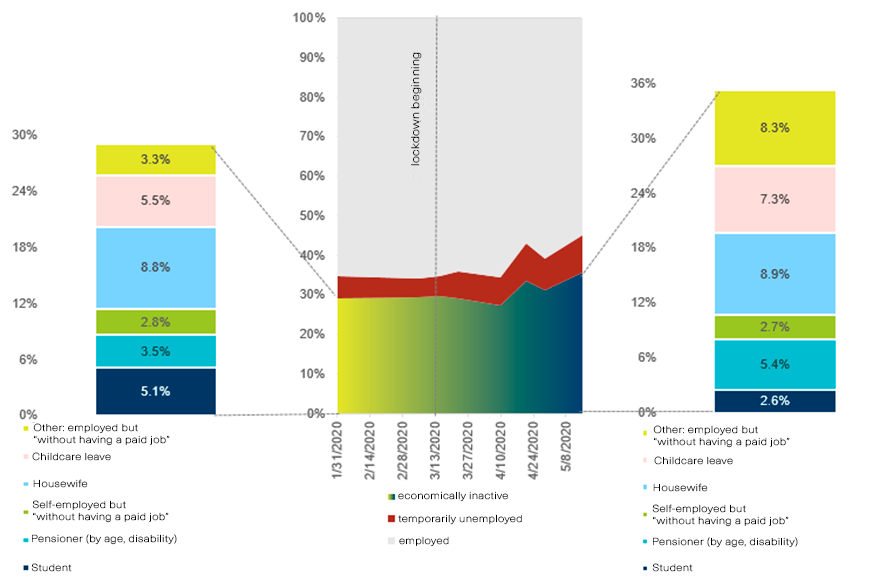

In fig. 3 and fig. 4 in the center is shown how the ratio of the groups we considered changed during January-May 2020, separately for men and women. We also consider the composition of the group of economically inactive at the beginning of the period (one and a half months before the quarantine) and at the end — in mid-May, when the first restrictions eases were made. As you can see, the results for men and women are very different.

Figure 3. Men in the labor market in January-May 2020: shares of employed, unemployed and economically inactive

Source: Gradus survey data

During the lockdown, the share of economically inactive men rose sharply from 11% to 24%. The share of economically inactive women before quarantine was much higher than that of men, primarily due to housewives and those on maternity leave. This share also increased, but not so rapidly.

The category that provides the lion’s share of the growth of the economically inactive, especially men, is the so-called “others”: people who noted that although they do not have a paid job, they consider themselves employed. We assume that these are those who were forced to go on unpaid leave or to stop working as an entrepreneur due to quarantine restrictions, or had not been working due to the temporary suspension of the employer.

The fact that the group of inactive women did not grow as much as men means that most of working women continued to work. An important reason for this is the specifics of “female” and “male” professions. Traditionally “female” industries include such as medicine, education, retail, which continued to operate during the period of restrictions (including distance education). Among the “male” professions are the transport industry, which was almost completely stopped in March and May. Some families could find themselves entirely dependent on women who kept their jobs.

Thus, despite the fact that men have suffered more from the economic crisis in terms of job loss or earnings, women have been significantly burdened, as most of them have continued to work, while performing even more household duties, including children care. This also applies to women who work in essential areas, not remotely, and have children (especially if they had no one to leave them with at home), and women at remote work who were simultaneously taking care of young children, which could also be very difficult.

Figure 4. Women in the labor market in January-May 2020: shares of employed, unemployed and economically inactive.

Source: Gradus survey data

The number of women who indicated that they were on childcare leave increased slightly (although statistically the increase was insignificant). This wording could have been chosen by women who were forced to leave work and stay at home with their children due to the closed educational institutions. There is also a noticeable increase in the share of female pensioners and a decrease in the share of female students (also statistically insignificant). Elderly workers who could not get to work could lose it or, for example, go on unpaid leave. Instead, more mobile students have more opportunities, such as working as salespeople or couriers. However, this is only our hypothesis.

In total, more than half of both unemployed and employed women in our sample have children, which means a sharp increase in the workload for each of them due to closed kindergartens and schools. Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention not only to those who have become unemployed, but also to all families with small children.

Recommendations on public policy

The greater burden on women, even in the short term, can have significant negative consequences for the health and quality of life not only of women themselves, but also of their families. In our opinion, the Government should consider and approve scenarios for short-term support for such families in the event of a recurrence of emergencies such as the spring lockdown. As an example, most European countries have taken this aspect of the coronavirus crisis seriously and have introduced a number of measures to reduce the burden on women. Appropriate may be:

- support for the operation of individual kindergartens or the partial operation of all kindergartens for the care of children whose parents cannot work remotely or work in essential areas (medicine, public transport, delivery and sale of prime necessities, utilities, police, important civil servants). Similar measures have been implemented in Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands;

- a possibility of obtaining additional paid leave for childcare (for example, up to 15 days in Italy).

- monetary measures of social support for families with children, for example, payment by the state of a share of wages or income of self-employed persons without actual working for it in case of kindergartens and schools closure (introduced in Portugal).

Long-term measures include the development of information policy aimed at instilling in society the idea of the need to actively involve men in household duties and childcare at the same level with women.

Appendix 1. Labor migration during quarantine.

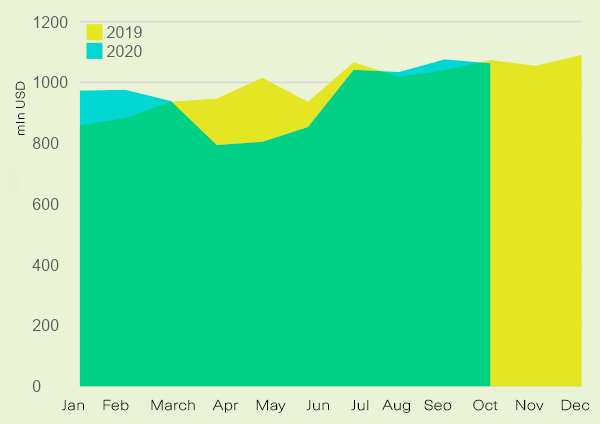

In mid-March, when most countries in the European Union had already announced a lockdown with the closure of borders, and when Ukraine also announced the closure of its own borders, there were many fears about the consequences of these actions due to the return of Ukrainian seasonal workers. Analysts’ fears were related to the expected sharp rise in unemployment, as well as the decline in remittances to Ukraine, which amounted to 10% of GDP before the crisis. To find out how this situation was resolved, let’s look at the dynamics of remittances compared to 2019 (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Dynamics of private remittances to Ukraine

Source: NBU

As it was expected, they fell in April and May. The maximum gap with the figure for 2019 was in May: 20% less. But from June they began to recover quickly, and from July they were at about the same level as a year ago.

Speaking of remittances, it is important to remember that we are talking about indicators in US dollars, while workers in EU countries receive income in either euros or local currencies. Most Ukrainian workers work hard in Poland and the Czech Republic, currencies of which have depreciated against the dollar since the crisis began. In April-May, the local currencies were 9% weaker than a year earlier. The same applies to Russia, where many Ukrainians still work. Thus, about half of the decline in transfers is due to the exchange rate effect. So, the real decline in workers’ incomes was less significant, and many of them managed to find ways not to leave their jobs in the EU even during the lockdown period.

Therefore, in January-October 2020 remittances were only 2% less than in the same period in 2019, which is much better than the forecasts that were heard in society in spring. Ukrainian workers were in demand in the EU, especially in the summer, so they were allowed to come. We see that regulation and the market have been adapting to the new reality for the benefit of both the EU economy and the Ukrainian economy.

Appendix 2. Research methodology

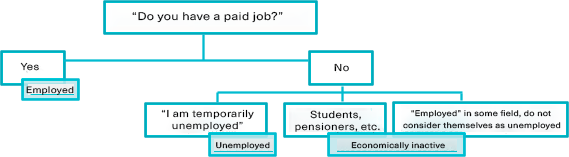

The Gradus online panel reflects the population structure of cities with a size of more than 50 thousand inhabitants aged 18-60 years (by age, gender, size of settlement and region). It is clear that urban dwellers are more likely to face economic problems as a result of the pandemic, so this sample contains useful information about their employment. Respondents were asked whether they had a paid job. Those who gave an affirmative answer, we include in the category of employed. Among those who said they did not have one, we single out the group of unemployed (those who noted that they were unemployed) and the group of the economically inactive (those who do not have a paid job but do not consider themselves unemployed).

The latter group is quite large, especially among women. We divide it into several subgroups. For men, these are students, pensioners, self-employed persons (these are those who work for themselves, but currently for some reason have no income, but do not consider themselves as unemployed). The fourth group, the “others”, is formed by those who have noted that they are employed in some field. By analogy with the third group, we consider them as those who are temporarily unemployed, but do not consider themselves unemployed, and therefore can not be classified as economically active. In the case of women, two more subgroups are added: women on childcare leave and, separately, women who are running a household.

Figure 6. Questions to respondents and the scheme of answers categorization

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations