Youth unemployment is an indication of wasted talents and underused economic resources; it spoils personal lives of the unemployed and leaves scars on their future career, earnings, health and social life. Ukrainian labour market seems to be more favorable for the young than in the EU countries. It is rather robust to the economic downturns. Youth unemployment of 15% rate in 2013 seems to be far less of a problem in Ukraine than it is in the EU where it reaches up to 55% at the extreme (Greece), with much wider gap between the young and 30+ people.

The article is based on the findings of research project EXCEPT and own contribution of the authors. EXCEPT is an EU funded research project within the Horizon 2020 Programme.. The aim of the EXCEPT project is to develop effective and innovative policy initiatives to help young people in Europe overcome labour market insecurities and related risks. Further information can be found at: http://www.except-project.eu/home/

Modern youth is more educated, healthy, lives in a more technologically advanced and economically developed world. Deloitte (2016), concludes about Millennials, people born in 1980-2000, – “They are no longer leaders of tomorrow, but increasingly, leaders of today”. One can check this by reading the “30 under 30” lists, looking at young digital start-uppers and civil society activists. At the same time the peers of these bright stars, though, cannot find a place for themselves in a contemporary world which – shaken by financial crises, wars and social unrests – appears to be harsh to the young. In some countries, they feel as insecure about their jobs as youth 50 years ago. In this column, we talk about youth unemployment in Ukraine and in the EU after the 2008 economic crisis and during recent downturns.

Why care about youth unemployment?

Being unemployed at any age is not a status to be appreciated. However, research shows that youth unemployment in particular may be extremely costly to the society implying many negative outcomes in terms of both material and mental wellbeing. First, the unemployment itself may make one feel miserable at the moment. But some consequences last far beyond unemployment periods.

For the society as a whole, youth unemployment is a waste of talents and human potential, waste of resources invested in education, and lost production. Jobless young decrease the basis for the state tax revenues, beside all, shifting the burden to sustain pensioners on the rest of the workers.

For the person, joblessness is dangerous because of its self-perpetuating nature – or “scarring” effects in later life. Experiencing unemployment shortly after finishing education sets in motion a whole range of adversities: lower pay, increased chances of subsequent unemployment spells, less life satisfaction and mental health problems in the adulthood. Longer periods out of job bring depreciation of skills and of self-confidence, and makes the CV less attractive for the employer. First 10 years of professional life define how high and how fast the person can climb the career ladder.

Youth unemployment frequently goes hand in hand with social exclusion. Jobless teen – if they cannot rely on family support – may suffer from insecurity, get into dependence from state support programmes, or lose social protection entirely. Jobs do not only bring income – jobs bring reputation, respect and social capital. Unemployed can frequently be excluded from the networks of more successful peers, and from many aspects of economic and cultural life, and unintendedly start to socialize with “wrong” people. At the extreme– such exclusion goes together with delinquency, drug and alcohol addiction, suicide etc.

Last, but not the least, youth unemployment is worrying since it may also be a symptom of other problems in the economy – like poorly designed labour market policies and regulations, institutional problems and flaws of the education system.

How big is the problem in Ukraine?

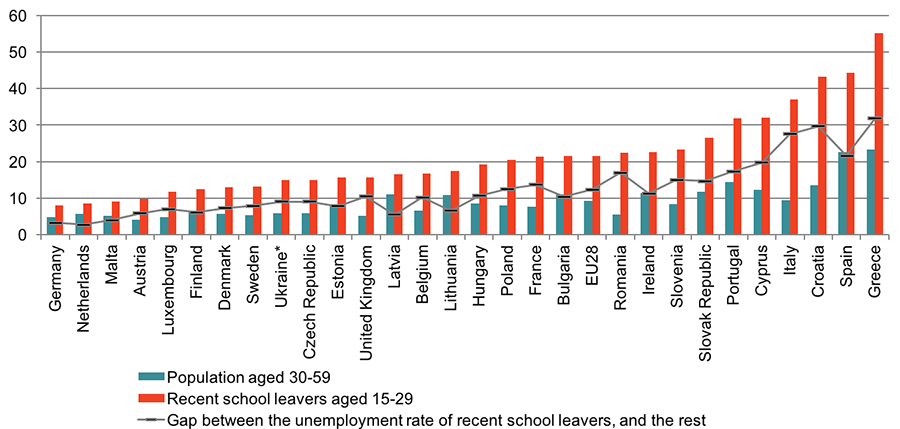

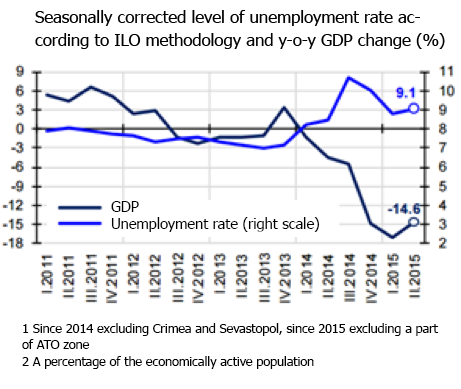

Unemployment rate is low. Youth unemployment rate is lower in Ukraine than the EU average indicator -15% youth unemployment in Ukraine as compared to 22% EU average. However, this indicates the severity of the problem in the EU. Figure 1 shows that- unemployment rates among the recent school leavers in six EU countries exceed one third, reaching 55% in Greece. The gap between the youth unemployment and adult unemployment ranges from 3% in Germany to 32% in Greece, with the EU average of 12%. Ukraine in this respect is below the average, with the gap between youth and adult unemployment being at 9%.

Figure 1. Unemployment rate for recent school leavers and population aged 30-59 in 2013

Source: Own calculations based on EU-LFS; *Source of data for Ukraine – Ukraine Labour Force Survey

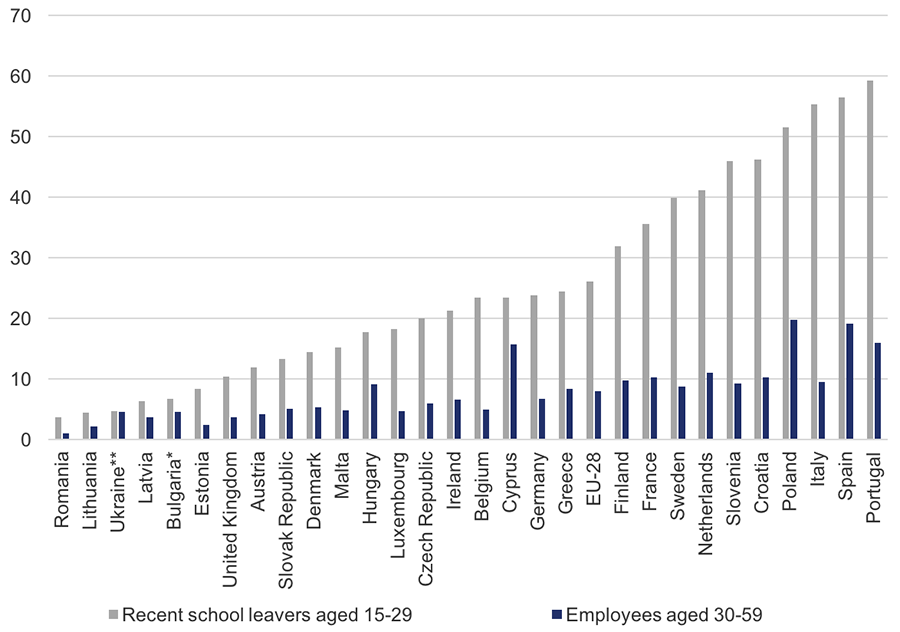

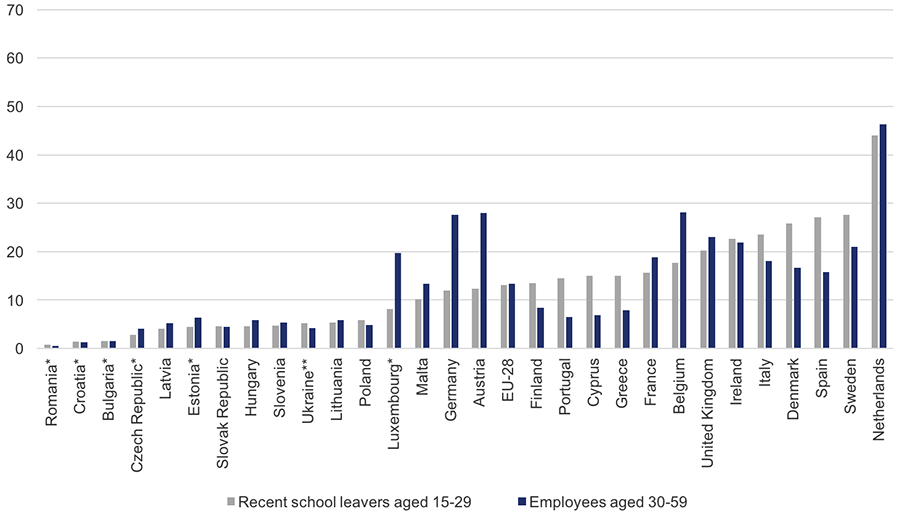

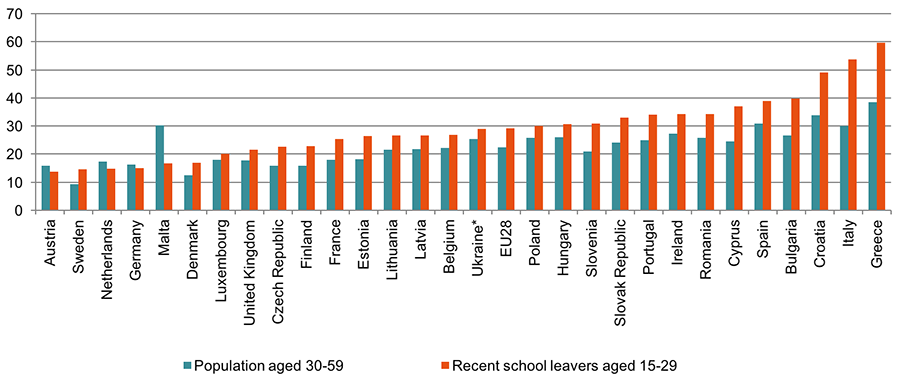

Insecure employment is rare. Temporary contracts and part-time employment in Ukraine – which are considered as insecure forms of employment – are also not manifested with high rates in Ukraine, and there is no evidence that insecure employment is observed among the young disproportionally more often than among the old (Figures 2 and 3). For instance, temporary contracts constitute about 4,6% among recent school leavers compared to 26% EU average, part-time employment – 5,3% compared to 13,3% EU average. For example, in Poland, Italy, Spain and Portugal, temporary contracts among the young constitute more than one half; part-time jobs are most spread in the Netherlands – about 44% of all recent school leavers’ employment. These types of employment arise because the employer is shifting the risk related to the uncertainty of the global market toward the employee. Youth is over-represented in the temporary jobs in the majority of the European countries because the young entrants of the labour market are less experienced and lack professional networks and reputation (OECD 2014). But the situation is different with respect to part-time contracts (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Temporary contracts among recent school leavers aged 15-29 and employees aged 30-59 in European countries in 2013 (%)

Source: Own calculations based on EU-LFS. Note: * less than 50 observations in recent school leavers group; **Source of data for Ukraine – ULFS; For Ukraine temporary contracts include temporary, seasonal contracts and casual work

Figure 3. Part-time jobs among recent school leavers aged 15-29 and employees aged 30-59 in European countries in 2013 (%)

Source: Own calculations based on EU-LFS. Note: * less than 50 observations in recent school leavers group; **Source of data for Ukraine – ULFS

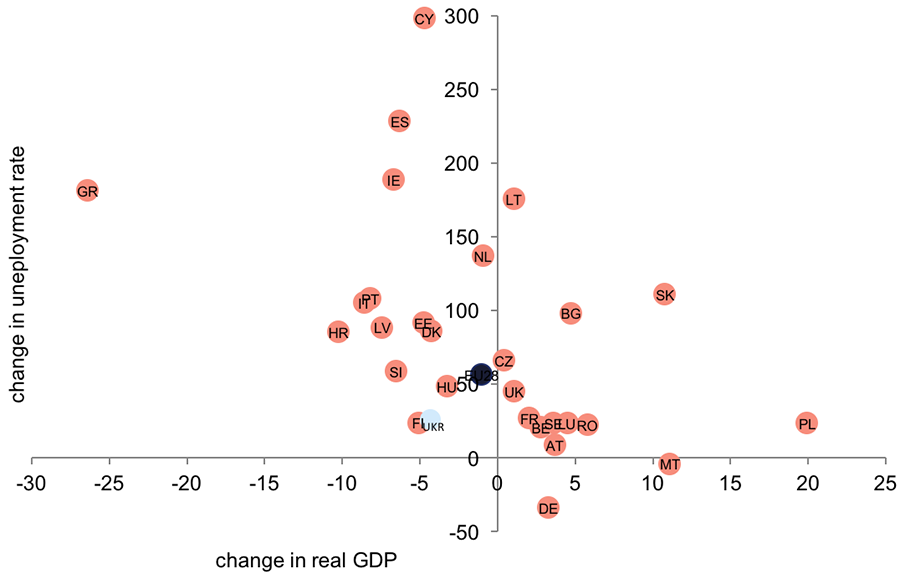

Youth labour market is robust to economic downturns. Ukrainian youth labour market also seems to be more robust when it comes to severe recessions. In 2013 Ukraine had a 4% lower real GDP than in 2007 – on par with many other countries like Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, Denmark – but the unemployment rate in Ukraine showed very insignificant response if compared to any other country with negative outcome for the real GDP (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Changes in the real GDP (%) and in youth unemployment rate 15-29 (%) between 2007 and 2013

Source: computations of GDP change based on World Development Indicators, World Bank; computations of change in unemployment rate based on Eurostat and State Statistics Service of Ukraine

Most recent economic crises in Ukraine also did not manifest itself in huge number of unemployed according to the official statistics: even with the consequent GDP yoy declines reaching cumulatively up to 20% – the unemployment rate was actually dropping and in second quarter of 2015 was at 9%.

Source: September NBU inflation report

Does this evidence mean that the recent school leavers in Ukraine have similar opportunities as young people in Sweden, Czech Republic, UK, Estonia or Belgium – countries close to Ukraine in terms of unemployment statistics? The answer is no.

Why Ukraine has low unemployment rates?

First, young labour force is a narrower group in Ukraine than in the majority of European countries. We can see it via comparing the high education attainment rates and comparatively high not in education neither in employment nor training (NEET) rates, which are excluded from the denominator for the unemployment rate calculations. According to the recent Global Competitiveness Index, Ukraine occupies 13th place out of 144 countries in terms of tertiary education enrolment rate – only Greece, Finland and Spain among the EU countries perform better. Ukraine has the highest share of young people (25-29) with tertiary education – 55% (EU average is 38%) and the share of people with only lower secondary education or below is the smallest – 5% (EU average is 15%). This phenomenon has ambiguous relation with the unemployment rate among the young. On the one hand, country with low demand for young professionals creates stimulus to spend more years in education, on the other hand, the more people are studying the lower is the labour market participation rate.

29% of Ukrainians (equal to the EU average), which is quite a high number, are not in education neither in employment nor training. This phenomenon is partly rooted in culture (Chiuri and Del Boca, 2008). The welfare costs of high youth unemployment are frequently lower in cultures where there is widespread social acceptance of children staying with their parents well beyond completion of school. Taking into account large share of students and large share of inactive young, we see that the unemployment rate is indeed low in Ukraine, but this rate refers to a comparatively small group of the young.

Figure 5. Proportion of NEETs among recent school leavers and population aged 30-59 in 2013

Source: Own calculations based on EU-LFS; *Source of data for Ukraine – Ukraine Labour Force Survey

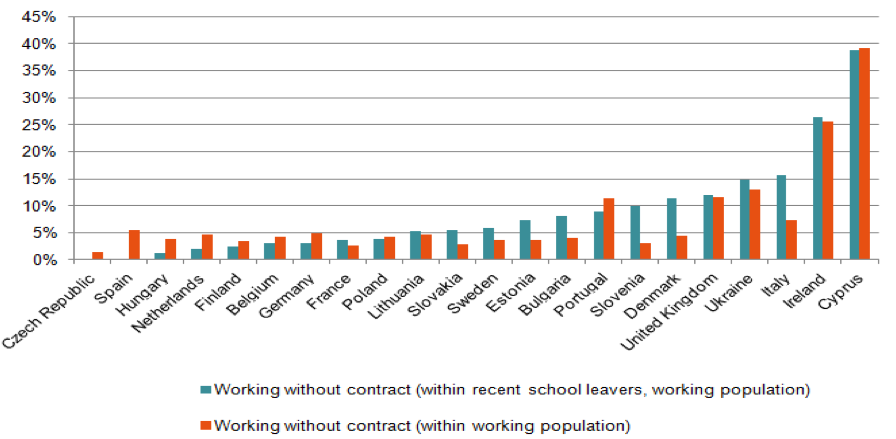

Second, more than 15% of the young people do have an informal sector job. Had the country stronger regulations of the employer-employee relations like in many EU countries (other things being equal) – these people would be unemployed. According to the ESS, Ukraine is one of the leaders in terms of work out of the national legal framework. Only 2 European countries have higher informal employment rates than Ukraine – Ireland and Cyprus.

Figure 6. Informal dependent employment rates per country and its recent school leavers subpopulation (2012)

Source: Own calculations based on European Social Survey (ESS), 2012

Work in the informal sector is not only a problem of resulting fiscal deficits for the country or uncontrolled quality of production, but it is a job without protection of the person rights.

Weak institutions in Ukraine and poor workers’ rights protection – be it formal or informal sector – created unhealthy employer practices that help firms to adapt to the economic downturns. In particular, employers in the private sector may recur to wage arrears, forced unpaid leaves for workers, decrease in working hours, etc.

Third, finding a job in Ukraine may be easier, but less rewarding as compared to the EU. For example, the average wage in Ukraine is low, currently at about 170 USD per month, and the minimum wage is 60 USD per month, which makes Ukraine the lowest wage country in Europe. Minimum wage, as well as labour regulations overall (Gorry, 2013), as research shows, have a negative impact on the employment, especially among the young people. In countries like Ukraine, with comparatively low wage, comparatively weak voice of the labour unions and poor worker rights protection – the cost of hiring is low for the employer, and this increases the employment rate in Ukraine, particularly among the youth.

Conclusions

Youth unemployment is an indication of wasted talents and underused economic resources; it spoils personal lives of the unemployed and leaves scars on their future career, earnings, health and social life. Ukrainian labour market seems to be more favorable for the young than in the EU countries. It is rather robust to the economic downturns. Youth unemployment of 15% rate in 2013 seems to be far less of a problem in Ukraine than it is in the EU where it reaches up to 55% at the extreme (Greece), with much wider gap between the young and 30+ people. But favourable employment data hides low rates of participation in the labour market, insecure working conditions and long years of education which are not being rewarded. Moreover, young Ukrainians who work are getting lower wages than their peers in the EU, which in itself may have detrimental longer term effects.

Traditionally, labour market policies and reforms are on the periphery of the policy-makers attention. In spite of the numerous pre-elections promises of higher remuneration and creation of new workplaces. This phenomenon is to some extent justified because all the efforts to stimulate economic growth, liberalize markets, improve education, deregulate economy and reduce the tax burden do favour job creation and reduce structural unemployment. But labour market conditions are not only a derivative of economic development. They can also play a significant role either promoting economic development, or pulling it back by damaging human capital and decreasing productivity. For example, the 2016 Index of Economic Freedom puts Ukraine at the 147 place out of 186 by Labour Freedom with the score 47.9 and at the 162 place in the overall world ranking. The measure encompasses various aspects of the legal and regulatory framework of a country’s labour market, including regulations concerning minimum wages, laws inhibiting layoffs, severance requirements, and measurable regulatory restraints on hiring and hours worked, plus the labour force participation rate as an indicative measure of employment opportunities in the labour market. To get closer to the successful economies – like Hong Kong, Singapore, United Kingdom, or United States – Ukraine has to speed up its work on the Labor Code, draft of which at the moment seem to be strongly criticised by the workers’ unions. However, one must not forget that with weak law enforcement, even the best legislation is worth nothing. So, both improved Labour legislation and properly functioning legal system are key to improving the functioning of the labour markets and create more opportunities both for young and for old.

*All calculations are based on the report M. Rokicka, M. Kłobuszewska, M. Palczyńska, N. Shapoval & J. Stasiowski “EXCEPT Working Paper No. 1 “Composition and cumulative disadvantage of youth across Europe” in the EXCEPT project.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations