Almost one million Ukrainian refugees remain in Poland after more than 800 days of the full-scale Russian aggression. In this article, we explore happiness, trust and self-declared health of Ukrainian refugees in Poland and Ukrainians who stayed in Ukraine. We find that refugees are less well off both in terms of their general wellbeing (happiness) and also economically compared to their Ukraine-based peers. In addition, past experience of violence lowers happiness, generalized trust and health of Ukrainians in both countries.

What do we know about Ukrainian refugees in Poland?

The full-scale russian aggression caused the largest displacement of population in Europe after World War II forcing many Ukrainians to become refugees or internally displaced. Two years later Poland still hosts 960 thousand Ukrainian refugees which is the second largest number in the EU after Germany. Yet little is known about the refugees’ socio-economic characteristics in comparison to those who stayed in Ukraine (unfortunately, we have too little data on IDPs and thus cannot analyze them as a separate group), or about the factors which induced Ukrainians to leave their country during the full-scale aggression.

In our new working paper (Fidrmuc, Obrizan and Stanek, 2024) we fill this gap by analyzing the differences in three socio-economic outcomes of Ukrainians in Poland and Ukraine, and in particular, their response to violence. Specifically, we are interested in what determines whether a person reports to be happy, trusts others and has good self-rated health. To study these questions we used data from two sources. First, we surveyed over 400 Ukrainian refugees in the Cracow area (Poland) who filled in an online questionnaire in November/December 2023. Second, we commissioned five questions to be included in the December 2023 wave of the nationally-representative survey of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (KIIS). For each question, we converted the original five-point scale question to a binary indicator, with 1 for respondents who chose the “yes” or “rather yes” options and 0 for those choosing the remaining options. In addition, we analyze how Ukrainians in the Polish subsample differ from those in a nationally representative sample of Ukrainians who stayed in their home country.

Surprisingly, previous literature found a mixed (and not always negative) effect of violence on socio-economic outcomes. For example, Kijewski (2020) showed that war experience (being injured or having had parents or grandparents injured or killed during WWII) decreases life satisfaction by about 0.1 (on a scale of 1 to 10) even sixty years later. On the contrary, Djankov et al. (2016), using a similar specification and the same dataset, find no significant effect of the same war experience. Victimization in recent civil wars goes together with reduced generalized trust (Grosjean 2014). Roy and Ray (2018) argue that armed conflicts are strongly associated with a dramatic devastating impact on public health. Obrizan and Iavorskyi (2023), on the other hand, found no statistically significant effect on population health in war-affected regions of Donbas in 2015-2016 for the majority of disease classes compared to the data in 2012-2013 before the war.

How different are refugees from those who stayed in Ukraine?

We combined the two (Polish and Ukrainian) surveys, resulting in a merged dataset with 2314 observations (1980 in the Ukrainian sample and 334 in the Polish sample, after dropping missing observations). A comparison of medians indicates that Ukrainian and Polish samples differ with respect to many characteristics. In particular, respondents from the Polish subsample are more likely to be female (90.7% vs 56.0%) and younger (the average age is 38.1 vs 53.1 years), are urban residents (49.4% vs 29.3% come from cities with more than 500 thousand inhabitants), are more likely to have visited the EU before 24.02.2022 as a tourist (72.2% vs 32.4%), have higher education (82.3% vs 43.2%), and are more likely to be professionals with higher education (40.4% vs 19.3%) or unemployed (23.4% vs 2.9%).

At the same time, Ukrainians in the Polish sample are less likely to graduate from a technical school (3.3% vs 34.5%), be a retiree (0.3% vs 37.2%), report injuries or death of close contact (12.6% vs 22.4%) and have experienced a minor inconvenience after the full-scale russian aggression (58.4% vs 69.1%; in this question respondents could choose 0 or multiple types of violence that they have experienced). The two samples are not different based on the comparison of medians for the other covariates. The observed differences are expected given that most men under 60 cannot leave Ukraine under martial law making younger women with children the main group of refugees.

Most importantly, Ukrainians in Poland are more likely to self-report good or very good health (51.2% vs 31.2%) but are not different with respect to the other two socio-economic outcomes: both samples demonstrate a similar level of happiness (62.6% in Ukrainian and 64.4% in Polish samples report being happy or rather happy) and trust (28.6% in Ukrainian and 29.0% in Polish samples report that they trust or rather trust others). The observed differences could be interpreted as one more confirmation of the strong self-selection of external refugees from the russian aggression (see, e.g., Kohlenberger et al., 2023).

How does violence affect socio-economic outcomes?

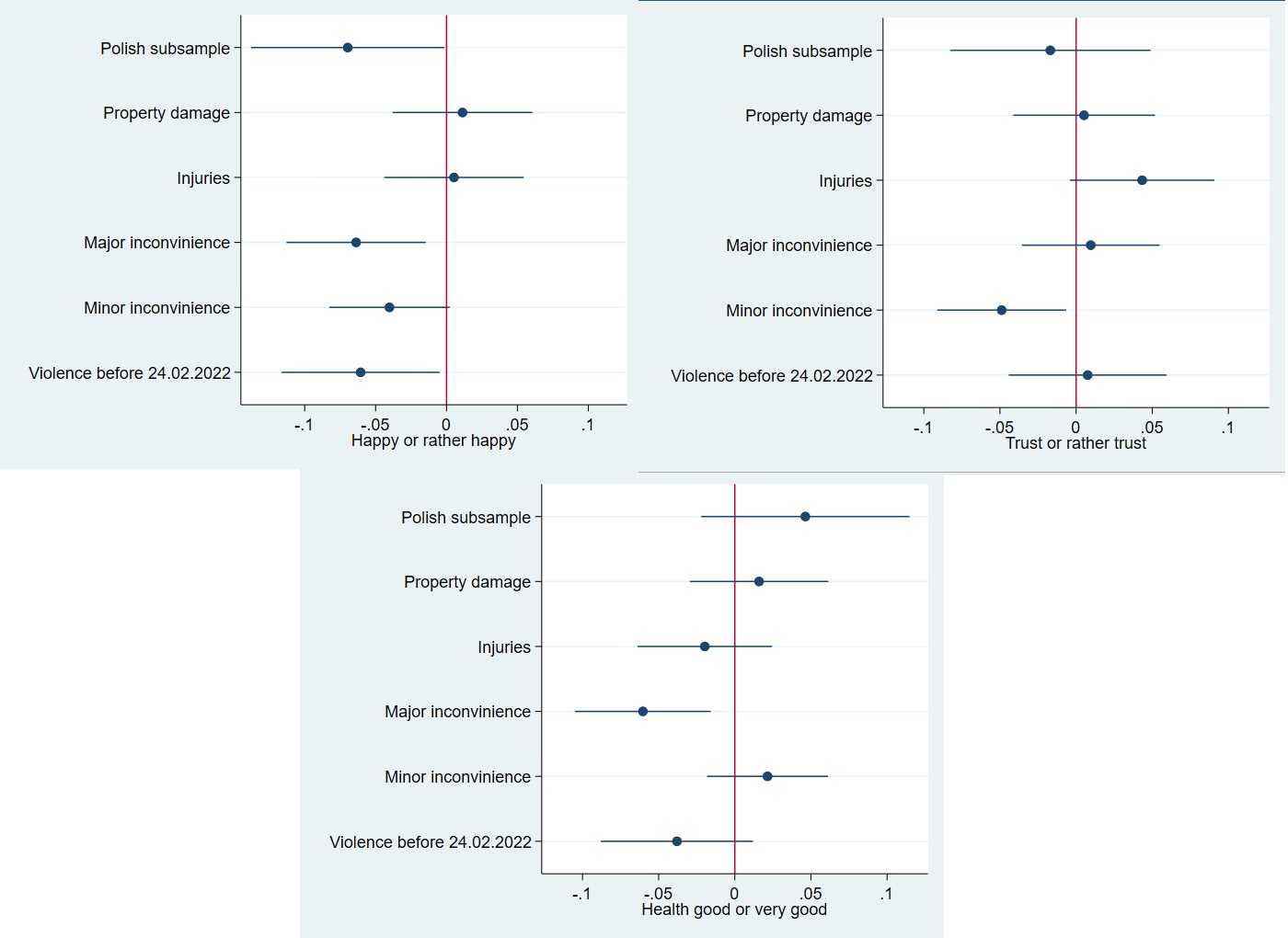

Our primary focus in this article is on the effects of violence on socio-economic outcomes. We report selected coefficients from our regression models in Figure 1.

Surprisingly, the most tragic events – injuries or deaths of close contacts – are not associated with reduced socio-economic outcomes in a statistical sense. Even more surprising is the marginally significant (at 10%) and positive association between injuries of a close contact and trust in others (higher by 4.3 percentage points). Perhaps, war victims who experienced injuries in their close circle and survived trust the others more because it was the support from people around them, often strangers, that helped them survive.

On the other hand, a major inconvenience, like a life-threatening lack of food, is associated with a 6.4% points lower probability of being happy and a 6.0% lower probability of good or very good self-rated health. In addition, experiencing any violence before the 2022 full-scale aggression is associated with an additional 6.1% points lower probability of being happy while minor inconveniences (like blackouts) are associated with 4.9% points lower chance of trusting others.

Figure 1. Results from linear probability models

Notes: Authors’ calculations based on the KIIS Omnibus survey and KRAUKLAB survey. The models also include a full list of characteristics which are not reported to save space. The base category includes living in settlements with less than 20 thousand people, being a manual worker, having high school education or less, not having enough money for food. Lines represent a 95% confidence interval.

Other interesting observations (statistically significant at 5%) include 7% points lower reported happiness of Ukrainians in the Polish subsample. This could be due to the separation from their family and friends, economic hardship due to living in a foreign country, uncertainty about the future of themselves and Ukraine or the result of traumatic experiences before and during their escape from Ukraine. Prior work experience in the EU, on the other hand, has a protective effect with 8.2% points higher chances of being happy or rather happy.

Better education is associated with a higher probability of being happy, trusting others and reporting good health. In particular, respondents with higher education report 11.6% points higher chances of being happy, 7.9% points higher probability of trusting others and 7.8% points higher probability of being in good health.

Likewise, higher subjective evaluation of one’s economic situation is associated with better socio-economic outcomes compared to the base category of those not having money for food. For example, respondents who could afford some expensive things report 37.1% points higher chances of being happy, 12.6% points higher probability of trusting others and 25.3% points higher probability of reporting being in good health which is consistent with some previous studies (i.e. Coupé and Obrizan 2024).

Concluding remarks

The study investigates the effects of war violence on socio-economic outcomes of Ukrainians who stayed at home or became refugees in Poland. Surprisingly, those who experienced injuries in their close circle show a slight increase in trust, likely due to the support received during crises. Major inconveniences, such as severe food shortages, significantly lower happiness and subjective health. Violence before the 2022 full-scale aggression also reduces happiness, and minor inconveniences like blackouts decrease trust.

Ukrainians in Poland report lower happiness, potentially due to separation from family, economic hardship, and uncertainty, though prior EU work experience offers some protection in this respect.

Higher education and better economic conditions strongly correlate with improved happiness, trust, and health, emphasizing the positive impact of economic stability and education on socio-economic well-being.

Thus, our results identify the substantial socio-economic costs of russian aggression in Ukraine, extending beyond killings, injuries, and infrastructure destruction.

References

Coupé, T, and M Obrizan. 2024. War and Happiness. University of Canterbury. Department of Economics and Finance. Working Paper No 6/2024.

Djankov, S., Nikolova, E. and Zilinsky, J., 2016. The happiness gap in Eastern Europe. Journal of comparative economics, 44(1), pp.108-124.

Fidrmuc J, Obrizan M and P. Stanek. 2024. Violence and Socio-economic Outcomes of Ukrainian Refugees in Poland. Working paper.

Grosjean, P. 2014. “Conflict and Social and Political Preferences: Evidence from World War II and Civil Conflict in 35 European Countries.” Comparative Economic Studies 56: 424-451.

Kijewski, S. (2020). “Life satisfaction sixty years after World War II: the lasting impact of war across generations.” Applied Research in Quality of Life 15(5): 1253-1284.

Kohlenberger, J., Buber-Ennser, I., Pędziwiatr, K., Rengs, B., Setz, I., Brzozowski, J., Riederer, B., Tarasiuk, O. and Pronizius, E., 2023. High self-selection of Ukrainian refugees into Europe: Evidence from Kraków and Vienna. Plos one, 18(12), p.e0279783.

Obrizan, M. and Iavorskyi, P., 2023. Health consequences of the war in Eastern Ukraine: comparing 2015-16 to 2012-13. European Journal of Comparative Economics, 20(2), pp.239-263.

Roy, K. and Ray, S., 2018. War and epidemics: A chronicle of infectious diseases. Journal of Marine Medical Society, 20(1), pp.50-54.

Disclaimer. The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations.

This research was financed with funds from the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP – FOR UKRAINE Programme) and Lille Économie Management (LEM). Neither the FNP nor the LEM had any direct involvement in the research design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in the writing of the report