Poor protection of property rights by Ukrainian judiciary has been a major obstacle to foreign investment for a long time. Inside the country, it has had one of the lowest levels of trust (according to the survey of the Institute of Sociology, in 2018 only 0.8% of people completely trusted and 6.3% somewhat trusted the courts, and this level has been more or less stable – see Figure 1). The latest polls suggest that judicial reform is among top-5 priorities of Ukrainian citizens. Indeed, any progressive legislation loses sense if there is no mechanism to enforce it. And it is hard to expect economic growth if basic rights of agents, including property rights, are unprotected.

Judicial reform has been on the agenda of many Ukrainian governments. In fact, some of Ukrainian presidents tried to reform the system before, but these reforms were not aimed at making the system a truly law-protecting rather than a repressive tool. The results of such ‘reforms’ have been fully felt during the Euromaidan, when courts sentenced people on the basis of fake police protocols or without any evidence.

An early attempt to ‘reload’ the courts was implemented in 2014 – heads of all primary-level courts were dismissed. However, 85 per cent of them were re-elected by the staff of the respective courts. Thus it was clear that judicial system needs much more than that. At the same time, reforming courts is one of the hardest tasks because the government has to find a balance between integrity of the judiciary and its independence.

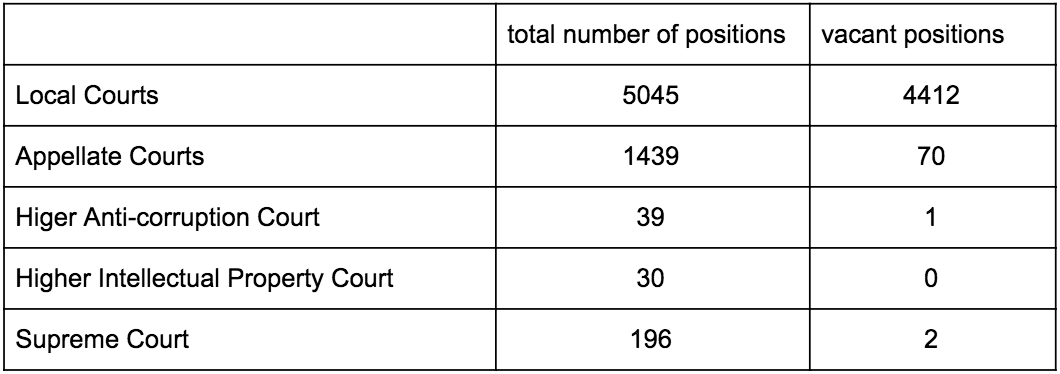

The Strategy for reforming the judicial system was adopted in 2015. Already in the early 2015, the law “On the right to justice” was adopted. It strengthened the role of the Supreme Court and streamlined some of the court procedures. Voluntary ‘cleaning’ of the judicial branch started in 2015 with introduction of e-declarations – about 2000 of 9000 judges left their positions unwilling to declare their assets. Mandatory cleaning of the judiciary, i.e. re-attestation of judges has been underway since 2016. As of end-2018, over 20% of judges that underwent the re-attestation procedure did not pass it. Today, the system has over 4000 vacancies (table 1). Naturally, lack of judges causes overload on the remaining judges and prolonged consideration of cases. This is the price one has to pay for higher quality of the judiciary.

Table 1. Number of positions and vacancies in Ukrainian courts

Source: Higher Qualification Commission of Judges

The major reform of the system started with amendments to the Constitution in summer 2016, complemented by the new law on Judicial system, on the Higher Council of Justice (which is the self-governing body responsible among other for prudential oversight of judges and disciplinary actions towards them) and amendments to the court procedure.

All in all, the judicial reform has brought up the following changes:

- the court system was changed from four-level to three-level one. The intermediate level between appellate courts and the Supreme Court introduced by former president Yanukovych was eliminated. The role of the Supreme Court was strengthened. An open competition for 196 positions in the Supreme Court started in 2017. In May 2019, 193 vacancies were filled. However, the Civic Integrity Council that had an advisory role in the selection procedure reports that 44 appointees have dubious reputation.

- the Higher Court on Intellectual Property and the Higher Anti-Corruption Court (HAC) were established in mid-2018. Establishment of the HAC was uneasy because this court completes the vertical of anti-corruption bodies – National Anti-Corruption Bureau (investigation), Anti-Corruption Prosecution and Anti-Corruption Court (conviction). In September 2019 the HAC started its operations. International experts played a major role in selection of the HAC judges. In fact, the willingness of the former president Poroshenko to undermine their role was one of the major obstacles to the adoption of the law on the HAC.

- the independence of the judiciary was strengthened along several lines. Firstly, selection and disciplinary actions towards judges are performed mostly by the professional community. Thus, if previously the Higher Council of Justice (HCJ) consisted of 10 representatives of judges and other lawyers and 10 representatives of executive and legislative power, today the ratio is 15 to 6. The Higher Qualification Commission of Judges (HQCJ – the body responsible for selection of judges) previously did not include representatives of attorneys and included a person from the Ministry of Justice. Now it includes two representatives of attorneys and no Ministry representatives. Secondly, judges now do not have a five-year ‘probation’ period. They are appointed once and for life (they can be dismissed by the HCJ if they commit a crime or ruin their reputation). However, the minimum age and experience needed to become a judge were raised. Thirdly, judges are appointed not by the parliament but by the Higher Council of Justice (the president formally signs the decree with appointment of judges recommended by the HCJ). At the same time, members of the HCJ and the HQCJ cannot work elsewhere while previously they were allowed to hold elected or executive offices. Finally, salaries of judges were increased multiple times. Simultaneously, judges are obliged to submit the declaration of their assets and revenues and the declaration of integrity, and their immunity was limited – now a judge can be detained if captured at the crime scene.

- the institution of attorneys was considerably strengthened – they received a lot of opportunities to protect their clients which were not available to them before. At the same time, only attorneys are allowed to represent a person in court, while previously anyone could do that (although the law which still has to be adopted can limit this clause only to criminal or otherwise significant cases).

- court procedures were streamlined – in particular, many have been transferred into electronic form (e-court), and an automatic distribution of cases among judges was introduced.

- to improve the enforcement of court decisions, private enforcement agents were allowed, and remuneration of public enforcement agents was linked to the results of their work.

Thus, the institutional carcass for the judicial reform is sound. However, its actual implementation is not flawless. For example, there were questions to the procedure of re-evaluation of judges. The Civic Integrity Council even issued a statement on its withdrawal from the process since too little time provided for the procedure did not allow to thoroughly evaluate candidates. After this statement the process slowed down and even was broadcasted via web-cams.

The process of reorganization of courts is not complete either. In fact, appellate courts were renamed rather than renewed. The consequences of half-reformed judicial system are quite obvious – for example, there is a number of dubious decisions on reversing the resolution of insolvent banks by the NBU, renewal on the job of many policemen dismissed upon attestation or of heads of state-owned enterprises fired within the SOE corporate governance reform. Thus, some courts are trying to reverse the reform progress, including that of judicial reform. A recent scandal revealed participation of Kyiv District Court in [sometimes successful] attempts to replace the HQCJ members to take this body under control of the executive branch. The respective recordings were released by the NABU but have not yielded any tangible results yet.

Both newly elected president, parliament and civic activists argue for the ‘reload’ of Higher Council of Justice and Higher Qualification Commission of Judges since these bodies did not properly implement their functions. NGOs argue for selection of members of these two bodies with the help of international experts and with increased role of the Civic Integrity Council using the same criteria that apply to judges. Whether the new government accelerates the judicial reform or reverses it remains to be seen.

Prosecution reform and police reform have been one of the biggest disappointments of the last five years since only the first steps were made in them. The prosecution was deprived of the general oversight function (a Soviet remnant) while its other operations are unchanged. Within the police reform, the brand new patrol police was created, and other policemen underwent the re-attestation procedure. However, only about 5-6% of policemen were fired as a result, and many renewed in their positions with the help of the courts. Since the rest of the police remains unreformed, the new people leave the new patrol police. And the trust of citizens to police as a whole is deteriorating.

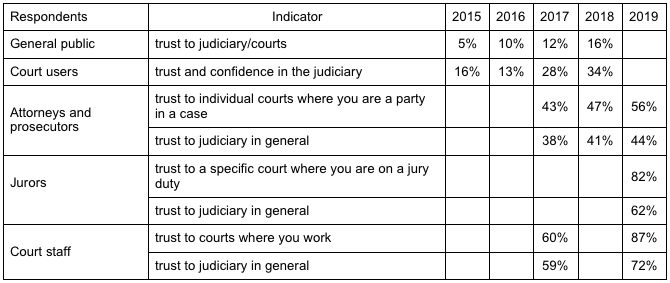

Figure 1. Trust to judiciary, prosecution, police. Panel A.

Note: the graph shows the share of people who said they trust or mostly trust in those who had a definite answer. Source: Institute of Sociology NASU surveys

Panel B.

Source: Democratic Initiatives Surveys

Table 3. Trust to judiciary by different types of respondents

Source: USAID “New Justice Program” surveys

You can find out more about the ‘White Paper on Reforms 2019’ project and other chapters of the book at this link

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations