In March 2019, before the first round of the presidential election, we interviewed a representative sample of 1,200 respondents about their views on the role of the state in the regulation over the economy as well as personal freedoms. We asked more than two dozen questions on the topic and created the first representative political compass of Ukraine. It shows that most of Ukrainians tend to believe that the state should have a strong influence on the economy and that personal freedoms should be restricted. Previous studies have shown that most well-known leaders of major political forces also tend to believe so. Ukrainian citizens and party leaders align on the political compass.

The material was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework of the project “Ukrainians on the Political Compass”. The material reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

Why do Ukrainians vote for certain politicians? The answer does not lie on the surface. The difference between the regions of residence or the age of voters can not explain everything that happened during the election. Therefore, we would like to go beyond and ask a wider question: what are the expectations of Ukrainians regarding the social and political system they live in? Should medical services be free in this system? To what extent is censorship allowed? What do they think about social benefits? We did not ask questions about political institutions per se. We rather focused on the issues of state regulations, economic redistribution and personal freedoms.? In total, we asked more than two dozen questions to a representative sample of 1,200 respondents. Design of our questions was based on the idea of a political compass.

Each citizen may have different views on the questions outlined above. But altogether these items can tell us a lot about the political ideas that are close to Ukrainians. In this article we focus on the ideological compass of Ukrainians. We will take a closer look at how this compass is related to the electoral behavior in the forthcoming materials.

Ukrainians are different. Some of us radically support the intervention of the state in the lives of citizens, while the other does vigorously oppose this idea. These two groups will be located at different poles of our compass. But there are also Ukrainians who will be somewhere between these extremes. Our analysis can show a whole range of such positions.

Measuring positions of people on a compass is not a new idea. The world media, our website, as well as other Ukrainian media, made their own versions of the political compass. All these polls shared one limitation – they were only seen by the audience of a specific site. This could be a problem, because not all Ukrainians use the Internet. In addition, not all of them regularly visit the resources that have placed the compass.

Thus, we made the next step and conducted the first representative survey of the political compass among Ukrainians.

How did we design the survey?

A national representative survey was conducted from March 7th to March 17th, 2019. Sample size 1,200 respondents. Sampling error does not exceed 3% with a confidence level of 95%. In addition to the questions of political compass, the questionnaire also included a wide range of items — from participation in EuroMaidan to media consumption.

Despite the relatively small size of the sample, we managed to catch the electoral tendencies of Ukrainians quite precisely. Table 1 shows that the results of our poll are very close to the results of other polls that used larger samples..

Table 1. Comparison of the VoxUkraine study with other ratings and results of the 1st round of elections

| If the presidential elections are held next Sunday and the following candidates are presented, who will you vote for? | ||||

| VoxUkraine survey

n=1200 7-17 March 2019 |

KIIS, | Sociological Group “Rating”, | Central Election Commission of Ukraine, | |

| Volodymyr Zelenskyi | 21.3% | 17.8% | 20.6% | 30.24% |

| Petro Poroshenko | 13.2% | 11.7% | 12.9% | 15.95% |

| Yulia Tymoshenko | 11.6% | 8.3% | 13% | 13.4% |

| Yurii Boiko | 7.3% | 7.1% | 7.4% | 11.67% |

| Anatolii Hrytsenko | 6.5% | 5.4% | 7.4% | 6.91% |

| Oleh Liashko | 3.7% | 3.4% | 4.2% | 5.48% |

| Oleksandr Vilkul | 2.4% | 2.6% | 3.1% | 4.15% |

| Ihor Smeshko | 2.2% | 2.8% | 2.7% | 6.04% |

| Other | 1.8% | – | 0.4% | – |

| Yevhen Murayev | 1.4% | – | – | – |

| Ruslan Koshulynskyi | 1.1% | 1.1% | 1.4% | 1.62% |

| Would cross out all the candidates | 2% | 2.2% | – | – |

| Would not participate in voting | 6.8% | 6% | 8.3% | – |

| Denial from answering | 4% | 8.9% | – | – |

| Hard to say, undecided | 14.7% | 14.7% | 15.2% | – |

Figure. 1 Socio-demographic parameters of the sample (N=1200)

How did we select the questions?

Four years ago, we created the online test “Political compass” in order to engage our audience to learn about their political preferences. We adopted an international online survey Political Compass to the Ukrainian context. This compass included 40 questions (or 40 items).

For a new representative survey, we had to make a smaller version of the compass, since 40 scales are too much for a face-to-face interview with questionnaires printed on paper. We faced the task of selecting a small number of scales while maintaining the quality of information. Such a procedure for optimizing the questionnaire (or scale reduction) is typical for sociological and psychological research.

In order to achieve it, we analyzed 18,000 responses in our online test and made several statistical tests. We analyzed missing values and the consistency of items (Cronbach`s alpha test). We also applied the principal component analysis to check to what extent our scales are grouped around two phenomena on our compass – economic freedoms and personal freedoms. As a result of the analysis, we came up with 24 items

The list of 24 questions included in the final questionnaire

I will read the statement to you, and you say how much you agree with them on a scale from one to five, where 1 – “I totally disagree”, and 5 – “I totally agree”

- The state should always regulate big business

- Any authority can be questioned

- The state must ensure my old age

- The use of light drugs, such as marijuana, should not be pursued as a crime

- The land must be a commodity that is sold and purchased

- Children have the right to have secrets from their parents

- A large business must financially support educational institutions at their location

- Graffiti on the walls is an art

- Economics with minimal state interference makes people freer in life

- Ukraine needs a strong leader with unlimited powers

- The state should financially support the internally displaced persons

- The death penalty must be restored

- Loss-making state-owned enterprises should be sold to private owners

- The primary purpose of a woman is to be a mother

- The state must guarantee free higher education

- Only a religious person can be moral

- All medical services should be free for citizens

- Same-sex couples should be given the right to conclude official marriage

- The state should take care of the welfare of every citizen

- The censorship of the media is necessary to ensure the moral standards in society

- Large industrial enterprises have to pay additional taxes for environmental pollution

- Organized protests and demonstrations should always be allowed

- The lack of state regulation of prices positively affects the economy

- When people receive privileges from the state, they do not want to work

What are the results?

Of the 1,200 respondents, only 8 people were unable to answer most if the 24 questions. We excluded them from the analysis. 12 items from our questionnaire were connected to economics, and the remaining 12 were related to the general moral issues. In both cases, issues were focused on restrictions. Every question can be thought of as a scale from the smallest to the largest.

We called the horizontal axis of the compass “from the left economic policy to the right economic policy”. In this case, the “left” economic policy will mean more state intervention in the economy, and “right” – less interference.

We called the vertical axis “from a democratic to an authoritarian control of rights and freedoms.” In this case, “democratic non-interference” means less interference in the life of the individual, and “authoritarian control” is more interference.

Disclaimer: In the English version of the article we refer to the vertical axes as libertarian versus authoritarian. There are some debates whether the word “libertarian” can be used in Ukrainian in the same context, thus we avoided it. However, in the English text we use it more freely

Each question of the compass sounded like a statement, which respondents assessed on a scale from 1 – “I totally disagree” to 5 – “I totally agree” (the scale of Likert). Then, we categorized each response as “bigger” or “lesser” support of the thesis.

If the respondent supports the thesis formulated in the question, the answer of the respondent is encoded as “1”. If he/she agrees partially, then “0.5”. We analyze everything else as “disagree” and labeled it as zero .

Please note that we look in detail in different shades of “agreed” (partially or completely). But we do not distinguish the shades of “disagree” (all options for us as one). We do this specifically to build a political compass (formula below). But for other tasks, the scale coding may be different.

Table 3. Example of questions in the questionnaire and their coding for analysis. I will read the statement to you, and you say how much you agree with them on a scale from one to five, where 1 – “I totally disagree”, and 5 – “I totally agree”

| disagree | I agree and disagree at the same time | agree | |||

| totally | partially | partially | totally | ||

| The state must guarantee free higher education | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Recoded – to what extent is this left economic policy? | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | ||

| The primary purpose of a woman is to be a mother | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Recoded – to what extent is this authoritarian control of personal rights and freedoms? | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | ||

The place of the respondent on the horizontal axis of the compass is calculated by the formula:

![]()

For the vertical axis:

![]()

Where r — the total support of the right economic policy, l — the total support of the left economic policy, a – total support for authoritarian interference in the life of the individual, d – total support for authoritarian non-interference in the life of the individual.

As a result, each respondent received a unique position on the compass, which was divided into four large squares: left-democratic, left-authoritarian, right-democratic, right-authoritarian.

To name each square of this compass is a non-trivial task that different researchers can perform in different ways, depending on theoretical assumptions and belonging to a certain intellectual tradition. We currently offer our own squares names to show the general trends in grouping respondents on the compass. But we are open to finding better (more precise) names for the poles, segments, and even the pixels of this compass.

Respondents on the compass

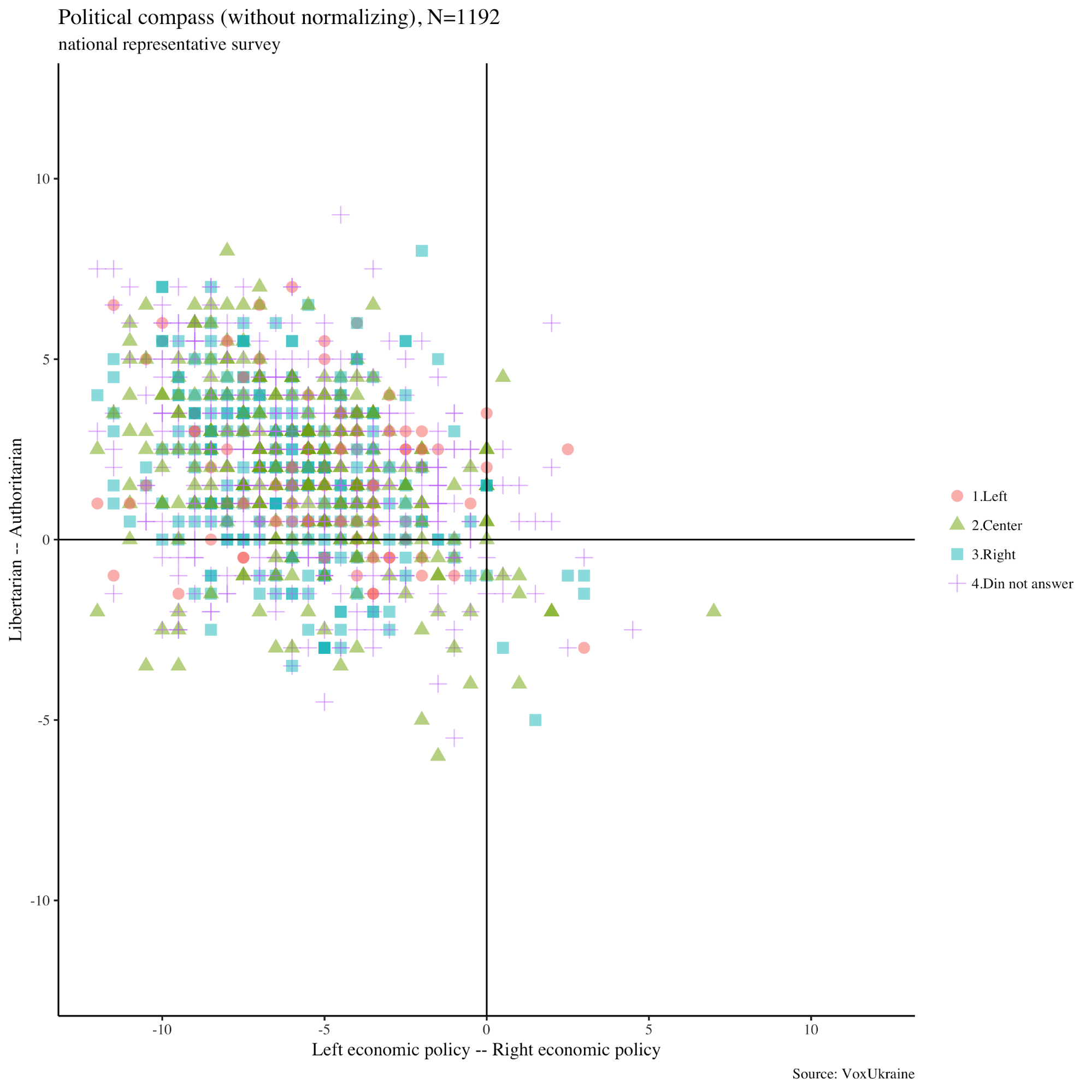

The final compass shows 1,192 respondents. 8 respondents dropped out of our analysis, as they did not answer most of the questions.

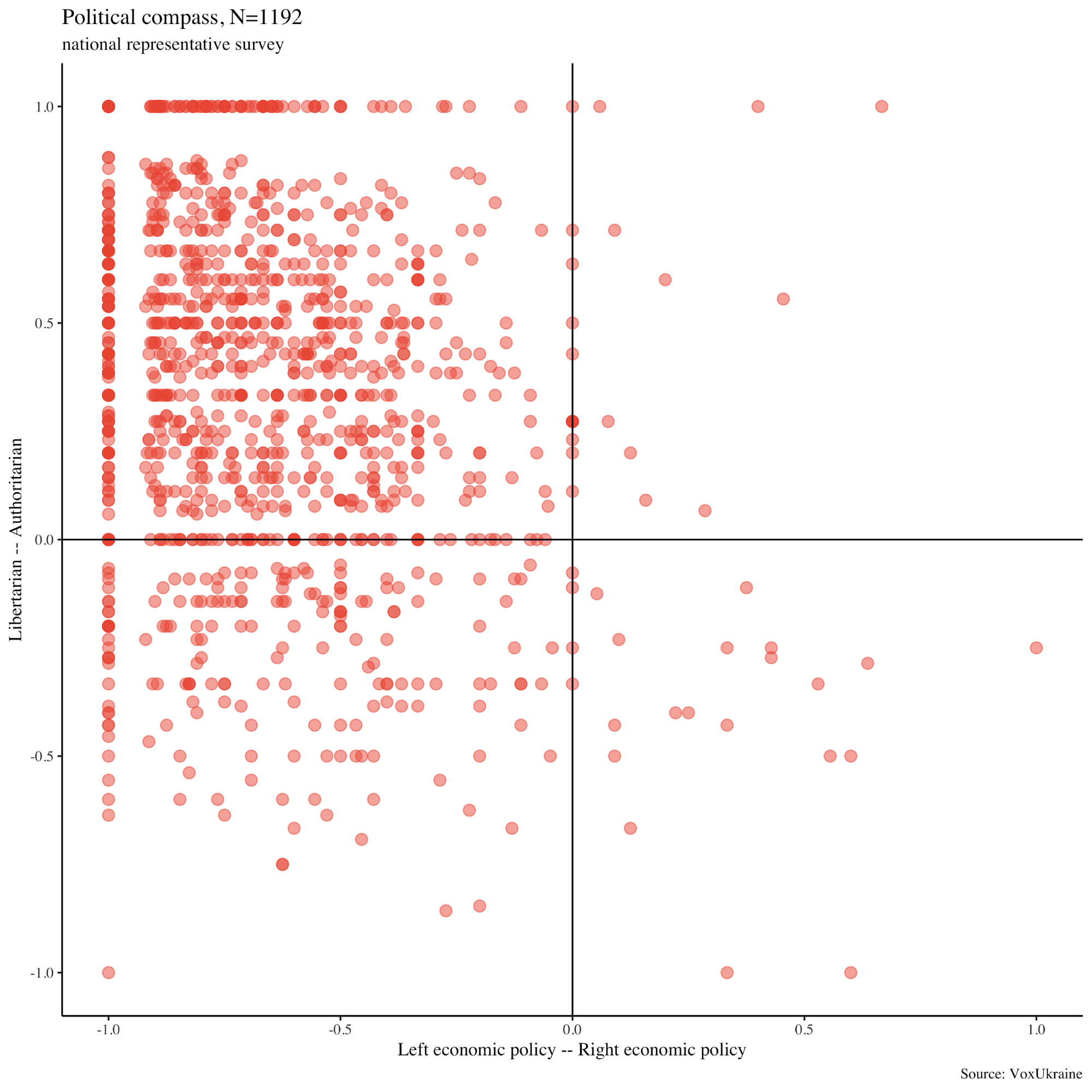

The vast majority of our respondents were located on the left side of the political compass (Figure 2). Most of them were in the upper square (“left-authoritarian”)

- Left-authoritarian – 73.3% respondents

- Left-democratic – 17.3% respondents

- Right-authoritarian – 1.0% respondents

- Right-democratic- 1.9% respondents

- Equal on scales (zero values) – 6.5% respondents (most of them on the left side of the compass).

Figure 2. Ideological positions of Ukrainians on the political compass

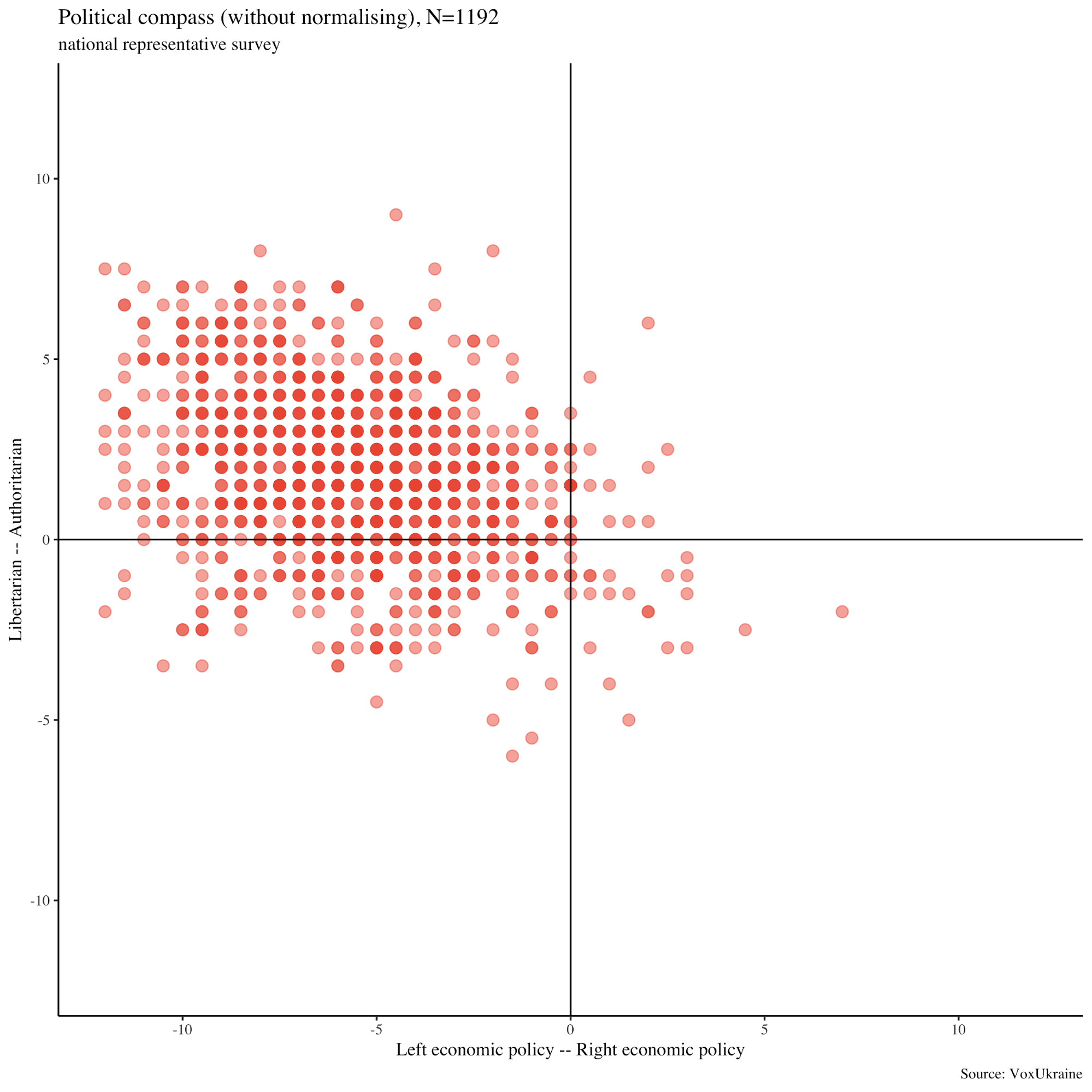

Disclaimer: please note that the extreme positions of respondents on the left axis (x = -1) are likely to be due to the higher rates of “I agree and disagree at the same time” answers. We have created other versions of our compass to deal with this issue by rescaling axes, yet the tendency remained the same. In simple words, here we did not normalize by the total answers as we did in the previous version of the compass. This new version of the compass is not present in the Ukrainian version of the article. We will explore this issue in the future articles. See Figure 2a for our new compass.

How are the positions of respondents on the compass relate to the self-determination of their ideology?

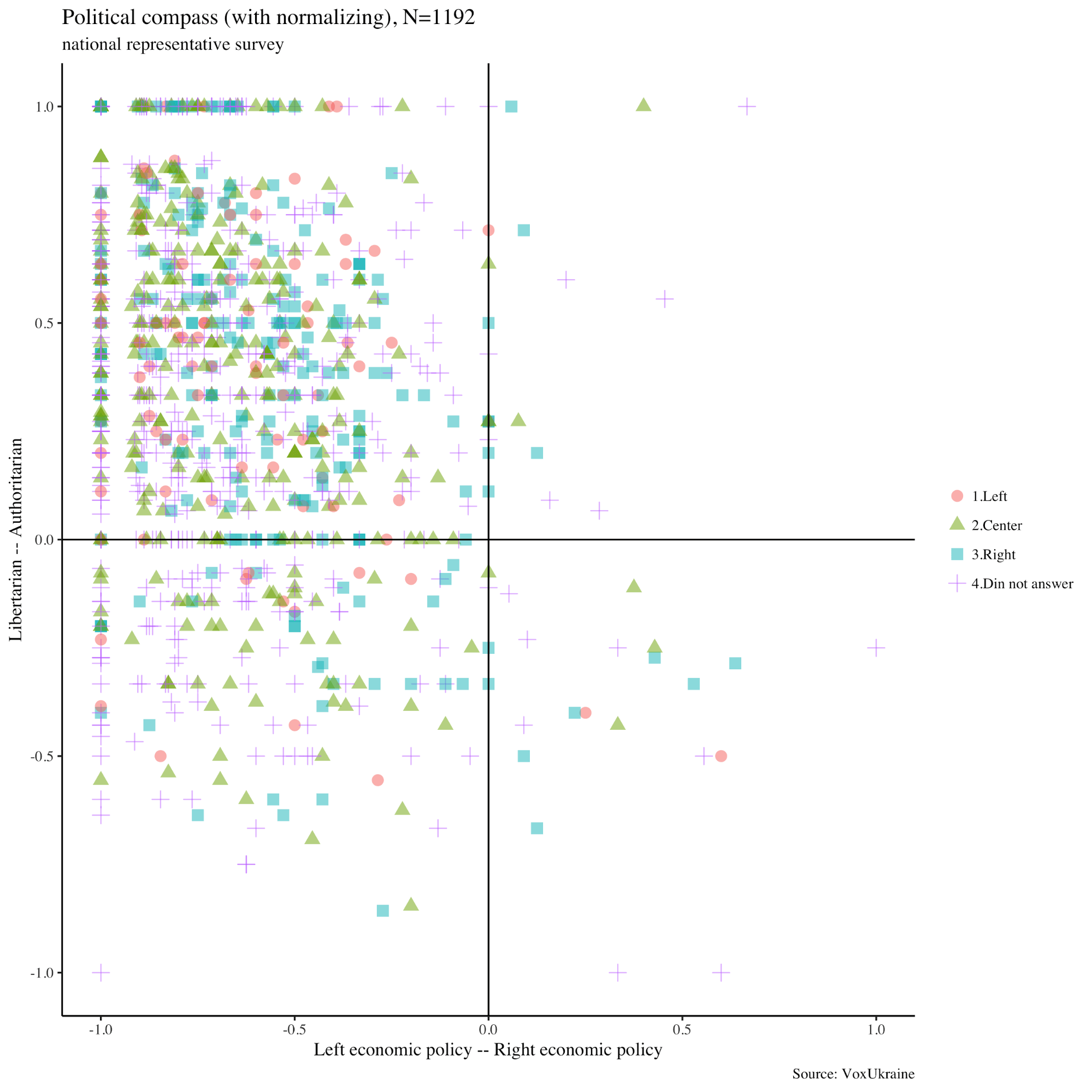

Note that the position of each respondent on the compass does not rely on their own idea of their ideological position. We do not know whether the respondents regard themselves as socialists, nationalists, anarchists or centrists. Nevertheless, if respondents have some own ideas about their ideology, we can put them on a compass. Actually for this we use different colors and shapes for our points (Figure 4).

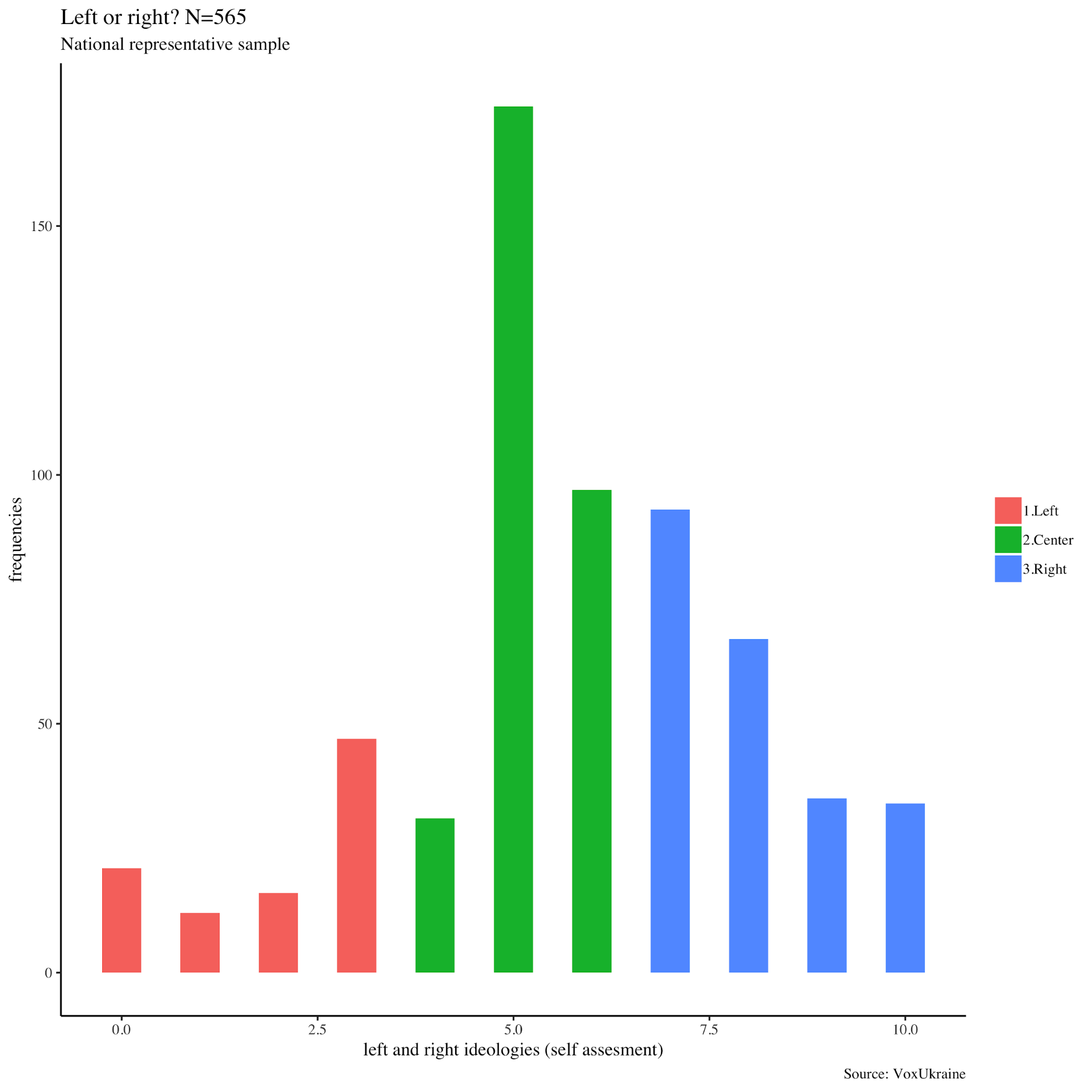

Our questionnaire included questions about the ideological self-identification of the respondent. Previous studies pointed out that Ukrainians often can not say whether they are left or right in the political spectrum. So, we decided to compare our compass against the simple “left-right” scale. ? (Image 3)

The question in the questionnaire was posed as follows:

Table 4. The question of subjective assessment of own ideology in the questionnaire. In politics, it is often told about “left” and “right”. Say where you put yourself on a scale where 0 means “Left”, and 10 means “Right”?

| “Left” | “Right” | |||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | I do not know what that is about | Difficult to answer |

| LEFT

8.1% respondents |

CENTER

25.3% respondents |

RIGHT

19.2% respondents |

DID NOT ANSWER

47.4% respondents |

|||||||||

All answers from 0 to 3 we coded as “left”, from 4 to 6 as “center”, and from 7 to 10 as “right”. In a separate category, we encoded those who did not understand the question and those who said that it was difficult for them to answer.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of responses of respondents (only for those who responded). 47.4% of respondents failed to answer this question and are not shown on Figure 3. Yet, these uncertain respondents will be depicted on a political compass along with everyone else.

Figure 3 Self-identification of respondents with a position on the “left”-“right” scale

Our analysis shows that respondents may not think or not know about the left and right ideologies, but nonetheless they can say whether they support state benefits, censorship, free higher education or not (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Subjective “left”-“right” scale and the political compass

Disclaimer: as mentioned above, the same data can be visualized on the compass without normalizing. Figure 4a is not present in the Ukrainian version of the text.

Figure 4a. Subjective “left”-“right” scale and the political compass (without normalising)

- Almost all respondents who called themselves “right in politics” were on the left side of our compass. 81% of them were in the “authoritarian-left” square.

- The majority of respondents who could not tell whether they were left or right were nevertheless also in an “authoritarian-left” square (76%). Much less (22%) were in the “democratic-left” square.

Summary. Theory and practice

Ideology is a very difficult term. It can be addressed from different positions, depending on the purpose and context of the research. In addition, ideology is not only a scientific or philosophical term, but an important concept for politicians themselves.

Despite the widespread belief that ideologies disappear in the modern world, a large number of politicians and intellectuals who are at the forefront of political processes do not quite agree with it. Juval Harari, discusses the positive aspects of nationalism, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez argue that left politics is very important for the US . In Ukraine, there is also a search for and building of political forces based on clear ideological positions. Even the advisers of the new president are talking about an libertarian ideology. Ukrainian public intellectuals do not lag behind politicians – this year Vladimir Yermolenko’s book on ideology was awarded by the prize named after Shevelev. Therefore, the theme of ideologies continues to be important and relevant for Ukraine and the world.

We can distinguish at least three great traditions of the study of ideologies:

- Ideologies can be studied as great narratives or codified and established systems of ideas. These ideas systems have their own historical names and historical context. They include nationalism, socialism, liberalism, and conservatism. Each ideology has its own carriers and champions. This ideology corresponds to a certain set of values, around which there is a political mobilization of various social groups

- Ideologies can be seen as the rules of the game by which society lives. They perform certain social functions (mobilizing and legitimizing) in order for the state to function. The state apparatus is responsible for ensuring that ideologies are legitimate and that all citizens are brought up in accordance with the prevailing ideology.

- Ideologies can also be studied as a set of coordinated positions (or the demand of citizens for ideology). One person may have a position that education and medicine should be guaranteed by the state. Another person may think that these services should be regulated by market mechanisms. Thus, these people have different ideological positions on how the economy should be organized.

In our study, we went the third way. Why? The first two approaches are general and abstract . In the first step, they assume the existence of large systems of ideas. Then, the disputes inevitably begin. For example, how many such systems are there? How can we attribute a particular politician or policy to a particular ideology (for example, where should we place Mahatma Gandhi or Hitler on political compass)? Another big question is whether ideologies have disappeared or just changed (and what has changed – their essence, form or means of existence in society)? Is populism a new form of ideology? These disputes often raise interesting questions, but rarely give definitive answers. And most importantly, these approaches lose what interests us – people and their political preferences. What the Ukrainians want, what they think and how they choose political leaders – these important issues disappear from the agenda if you choose the first two approaches.

Our approach does not come from pre-set assumptions about the existence of great ideas that are difficult to measure, correlate and determine, “whether they are alive or dead long ago.” Instead, we measure what people are thinking about important issues regarding the role of the state in their lives. Does the state have to regulate the economy and personal freedoms? We asked more than two dozen questions to see a more nuanced picture when compared to a one-dimensional approach.

For convenience, all responses of our sample can be displayed on a square of four segments, which we call the political compass. Even those people who do not know their own ideological position have their positions on this compass.

Our analysis shows that the majority of Ukrainians tend to believe that the state should have a strong influence on the economy and on personal freedoms. Coincidently, the same rhetoric dominates speeches of popular politicians who are also concentrated in this square of the political compass, despite their specific party affiliations and promises.

The material was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation within the framework of the project “Ukrainians on the Political Compass”. The material reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily coincide with the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

Publication of VoxUkraine’s materials wouldn’t be possible without institutional fundings from the USAID PACT Engage and the International Renaissance Foundation

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations