Recently, the Lviv City Council refused to allocate money for the construction of a city crematorium, citing the religiosity of the city’s residents. Sociologists Tymofiy Brik, Halyna Herasym, and Iryna Radiuk analyze data from surveys and in-depth interviews to gauge the impact of religion on cremation. Their data show that religious commitment is not an obstacle to perceiving cremation as the normal manner of burial. A cautious attitude toward cremation is not so much due to firm religious beliefs as to the fact that for many people, the process of cremation is something new and unfamiliar, which may result in misconceptions about the process of burning the dead and storing the ashes.

Trust but verify

In Ukraine today, there are 15 cities with IT clusters, 25 cities with international airports, and only three cities with crematoriums (which, nevertheless, is three times more than the number of cities with an IKEA store). For comparison, neighboring Poland has 52 crematoriums, Ireland, a country of about 5 million, has 4, and the United Kingdom has 307. Recent attempts to build a fourth crematorium in Ukraine failed. The city authorities in Lviv where a crematorium was to be built refused to allocate money for its construction. Interestingly, Ruslan Koshulynskyi, head of the Svoboda faction at the Lviv City Council, has consistently cited religious reasons. “90% of Lviv residents are Christian, and there are no cremation rites in the Christian burial tradition,” he explains. Koshulynskyi is not the only one to believe that religiosity feeds lukewarm attitudes toward cremation: many local media and politicians express similar ideas when there are initiatives to build crematoriums in various Ukrainian cities (e.g. Zhytomyr, Cherkasy, Uzhhorod, Vinnytsia).

But to what extent is referring to the citizens’ religiosity justified? Does their religiosity really affect their attitudes to cremation? Both Koshulynskyi and his opponents refer to historical and theological arguments, speculating about it but not proving it. Meanwhile, there was a survey in Lviv showing the respondents’ readiness to build a crematorium (the study showed that the clergy were not against cremation). In our study, we take the next step (1) analyzing the survey conducted in many cities, not just in Lviv (as the need for crematoriums is most acute in cities); (2) offering statistical models, not just descriptive statistics, and (3) citing data from in-depth interviews with clergy and believers from several cities in Ukraine.

Our analysis shows that the majority of Ukrainians (the Western region is no exception) are loyal to the idea of cremation. And interviews with priests and believers point to the fact that the “commitment to a traditional burial” attributed to them by Koshulynskyi is primarily due to infrastructure features rather than belief in the resurrection.

The survey was conducted in May 2020 using the Gradus app (N = 1000). It is an online panel that recruited Ukrainians aged 18-65 from cities of 50,000 or more. The Gradus panel’s age and sex structure correspond to that of the population of large cities of Ukraine. More information about the app and methodology can be found on the website.

Cremation: pros, cons, hidden pitfalls?

In May 2020, we asked respondents whether they would choose cremation or in-ground burial (Table 1). More than half of all respondents chose cremation (53% were in favor of cremation, 20% had no opinion, and 27% were in favor of burial). 44% of respondents from cities in Western Ukraine supported cremation, perhaps unexpectedly for Mr. Koshulynskyi.

Table 1. If it were about YOUR funeral. Which would you opt in favor of: cremation or burial?

| All | Western region | |

| Definitely CREMATION, not burial | 26.82% | 23% |

| Cremation rather than burial | 26.45% | 21% |

| Difficult to decide between these two options | 20.08% | 26% |

| Burial rather than cremation | 16.25% | 16% |

| Definitely BURIAL, not cremation | 10.40% | 14% |

Ukrainians are also quite tolerant of other people’s choices. We asked respondents what they thought about the cremation of relatives, allowing them to choose the answer “it depends on the individual and their attitude to it.” In this case, more than a third agreed that the other person’s opinion was decisive. In the Western region, 28% of respondents agreed with this position.

Table 2. If it were about YOUR RELATIVES. Which would you opt in favor of: cremation or burial?

| All | Western region | |

| It depends on the individual, their attitude to it | 34.59% | 28% |

| Definitely CREMATION, not burial | 9.47% | 5% |

| Cremation rather than burial | 13.12% | 8% |

| Difficult to decide between these two options | 14.31% | 24% |

| Burial rather than cremation | 17.09% | 18% |

| Definitely BURIAL, not cremation | 11.42% | 17% |

Our survey also shows that in the Western region, the demand for burial is slightly higher than that for cremation. Depending on the question, from a quarter to a third of respondents choose an in-ground burial. However, these figures are three times lower than Mr. Koshulynskyi would expect.

We also asked respondents what they think about cremation compared to in-ground burial. Half of the respondents in the Western region agreed that cremation is generally a better burial option than the traditional method (although this option is far from cheap in respondents’ eyes). Furthermore, 61% of them called cremation a more environmentally friendly manner of burial. Therefore, thinking that Ukrainian city dwellers have some sort of aversion to cremation is a wrong idea.

Table 3. Do you agree with the following statement? (“I somewhat agree” and “I completely agree”)

| All | Western region | |

| Cremation is a more ENVIRONMENTALLY FRIENDLY burial method than the traditional in-ground burial | 62% | 61% |

| Cremation is a CHEAPER burial method than the traditional in-ground burial | 37% | 32% |

| Cremation is a FASTER burial method than the traditional in-ground burial | 57% | 54% |

| Cremation is generally a BETTER burial method than the traditional in-ground burial | 54% | 50% |

We’ll all be there

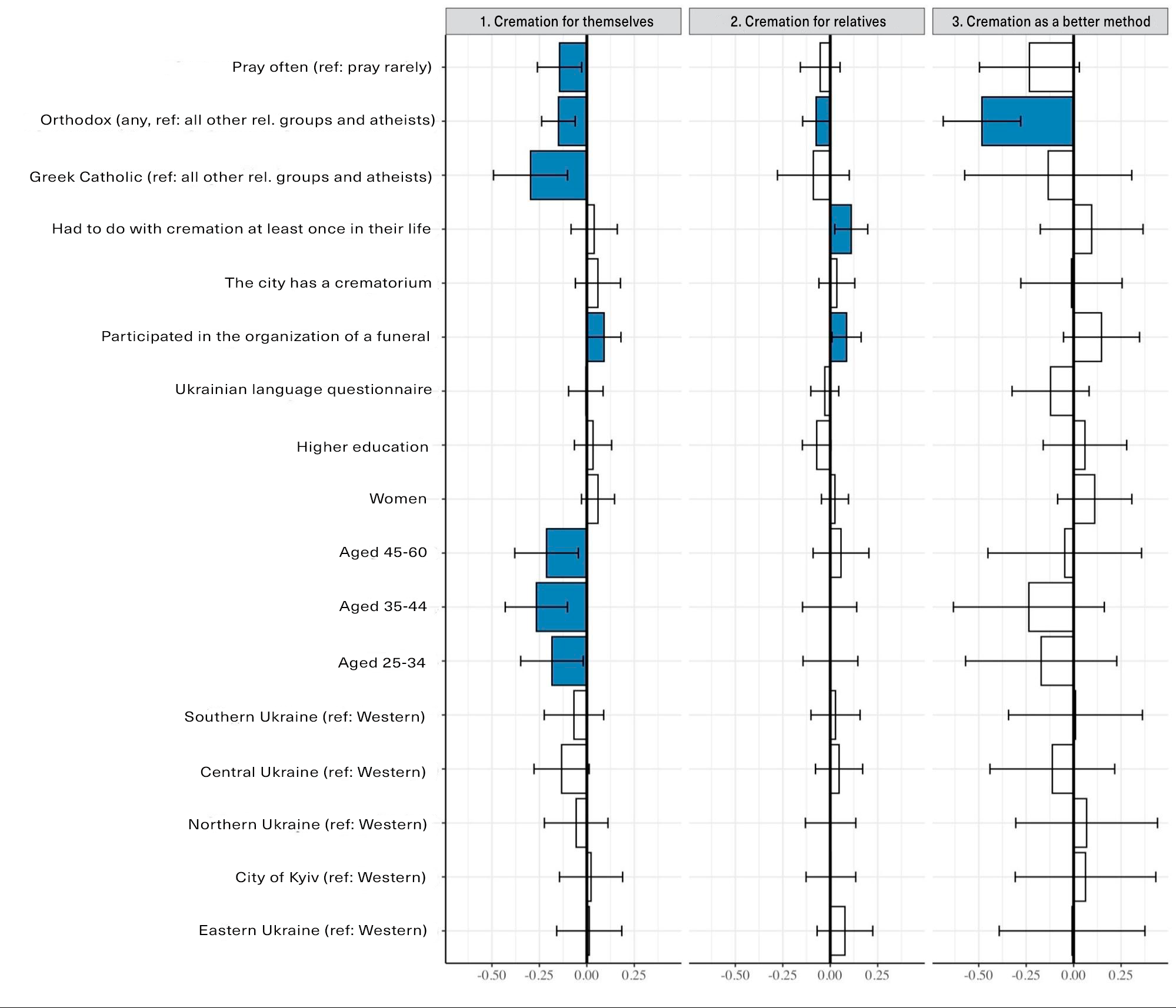

It remains to be seen whether respondents’ religiosity influences their attitudes about the manner of burial. To this end, we selected about half of the respondents (N = 529) who had participated in other surveys, in particular in those about their religious commitment (in April 2020 and January 2021). These respondents answered our questions about their religious affiliation and how often they prayed at home. We used a series of regression models to see the extent, to which respondents’ religiosity influenced their attitudes about cremation (Figure 1).

When it comes to choosing cremation for themselves or their close ones, Orthodox respondents (of any denomination) would indeed be less likely to choose cremation both for themselves and for their close ones. Orthodox respondents are also less inclined to agree with the statement that cremation is a better manner of burial. It is interesting, though, that Greek Catholics mostly living in Western Ukraine would be less likely to choose cremation only for themselves. In the case of cremation for their relatives, belonging to the Greek Catholic Church ceases to be statistically significant. Also in the case of general attitudes about cremation as a method (compared to burial), belonging to the Greek Catholic Church was not statistically significant. That is, Greek Catholics do not want to be cremated themselves, but are quite committed to the right of others to be cremated. Furthermore, they do not generally take a negative attitude toward cremation as a way of burial.

As for other variables, cremation is more likely to be chosen by young people under 25, as well as by those who have participated in the organization of a funeral. In the case of cremation for close relatives, age does not play a significant role. Interestingly, respondents who have had to do with cremation at least once are more likely to choose cremation for their near and dear ones. That is, the real experience (against which the local politicians in Lviv are protecting people so much) is a guarantee of a normal attitude to cremation.

Figure 1. Modeling the choice in favor of cremation (statistically significant effects are indicated in blue)*

* Model 1 and Model 2 are logistic regressions, Model 3 is a linear regression (in addition to linear regression, we also used the ordered logit model, obtaining the same results). The coefficients are not standardized. Significant coefficients are marked in blue.

Our grandfathers, great-grandfathers etc. were buried thus

Our team also conducted 20 in-depth interviews with believers, non-religious people and the clergy in cities with and without crematoriums. The interviews were conducted from May to December 2019.

From the in-depth interview material, it can be assumed that in a stressful situation, when a relative or friend dies, Ukrainians lack a clear understanding of the sequence of actions. Therefore, those responsible for funerals are more likely to follow the most common pattern, especially if a relative or a close family member dies suddenly: this way, you can rely on the support of experienced people around you. It is worth noting that one of the most important motives for choosing the manner of someone’s own burial is the desire to save their family and friends from unnecessary trouble and to maintain a connection with the family history. Furthermore, a wary attitude toward cremation might be not so much due to firm religious beliefs or the church’s position on it but because the residents of cities without crematoriums are not familiar with the cremation process, which may result in misconceptions about the process of incinerating a dead body and storing the ashes.

A non-religious man from a city without a crematorium remarked that despite his desire to be cremated, he would most likely be buried in the ground: “Well, that’s how we buried our grandparents, great-grandparents and so on.”

People living in cities with no crematoriums are more skeptical of cremation also because this burial method is little known to them and hence filled with various myths. However, it is not about religious motives, but about practical considerations. For instance, a respondent from Lviv who generally viewed cremation favorably, said that cremation was probably very expensive because, in his opinion, the price of gas in Ukraine was high. Cremation is actually often cheaper than a “traditional” funeral. A respondent from a city with a crematorium even noted that in her city, cremation is sometimes seen as an option “for the poor.” Therefore, even in the cities with crematoriums, some people may choose the burial method not for religious reasons, but for social or financial reasons: “when we had to bury one grandmother, there was no money, and she was cremated… And the other one was properly buried, in the ground, because we had more money”(a non-religious respondent from a city with a crematorium).

Overall, priests, believers, and atheists did not view the notion of the afterlife, salvation, etc., as an obstacle to cremation. It was mostly about quite “earthly” motives: besides the financial aspect, male and female respondents were concerned with preserving family memories, lying next to their close ones after death, being able to think and “communicate” with their deceased relatives. The male and female respondents from cities with crematoriums expressed concern that cremation would deprive them of this special place.

“I think it’s important to have such a thing as this monument, a tombstone. Usually outside the city, but not in the middle of a noisy city, which is specially dedicated and consecrated to commemorate the deceased. For the burial of bodies. I think it’s important that, in a sense, you need to get out of your usual place, make a small pilgrimage to a kind of shrine, which is the tomb of the deceased. And it’s the place not used for any other purpose, where you can come, remember, and think about your relatives.” A religious man from a city with no crematorium.

Analyzing the interviews with the clergy, we can assume that the city authorities in Ukraine (at least in the cities where Greek Catholics live) should primarily view churches not as rivals, but as partners in building crematoriums and debunking the myths surrounding cremation and superstitions about the burial process. The UGCC has success stories of combating the use of plastic flowers and floral tributes in cemeteries, whose experience can serve as an example. Respondents among the UGCC clergy repeatedly mentioned it:

“There’s just damage to nature and the environment, so I said it once, twice, asked last year, I asked everyone where I saw plastic flowers on the grave, I just said: what you’re doing is wrong, I tried to talk to them. I thanked everyone who didn’t bring them. So it’s slowly getting less (…). I speak to my congregation (…) most of them have already given up plastic.” Priest, UGCC.

Naturally, choosing the burial method is a much more sensitive topic than plastic flowers in cemeteries. As a UGCC priest rightly remarks: “If someone asks me if it’s possible [to burn the deceased], I’ll tell them that it is. But saying “go and burn your parents” (…) sounds weird to me. Probably, I won’t say it to the general public that yes, go to the crematorium, that’s it.” (Priest, UGCC).

The clergy often complain that they are primarily concerned with superstitions, not the manner of burial.

“Because there’s this one gesture that they’ve done all their life, they have a feeling that if they don’t, it means they’ve disgraced God or degraded the honor of the deceased. You see, sometimes you’ve got to ignore that [superstition] a bit.” Priest, UGCC

“Even though superstitions are partly related to some church things or acquire a pseudo-church look – for example, that something needs to be done with the candle that was held by the deceased – they still come from outside the Church (…). We need to talk about this and explain to people that this is not the way to do it.” Deacon, OCU

Fighting against superstitions can be the point of understanding between the city authorities and the church. For instance, one respondent from Lviv noted that she learned about the Greek Catholic Church’s not being against cremation when discussing various superstitions with believers in the church where she was working. Interestingly, during the interviews, the representatives of the UGCC clergy mostly noted that they learned about the Church’s stance on cremation not as part of the regular program in the seminary, but rather from practical experience. A priest from Lviv knew about cremation through his London experience, where there were Catholics who incinerated the bodies. Another seminary graduate got interested in the issue of cremation after an urn with ashes was brought to his native village to be buried near a relative.

Conclusion

The survey of big city residents showed that

- More than half of the respondents consider cremation for themselves. A third of the respondents agreed that the choice of cremation for relatives depends on the person and their attitude to it.

- Statistical models show that Greek Catholics are indeed less likely to consider cremation for themselves. But when it concerns cremation for their relatives or general attitudes about cremation as a burial method, belonging to Greek Catholicism is no longer statistically significant.

Thus, the Lviv politicians in vain point to people and their allegedly religiously motivated concern about cremation. At the same time, Ukrainian churches can become important partners in dispelling superstitions and misinformation surrounding cremation. If politicians really relied on people’s mood and expectations, their actions would be to the contrary — recognizing the right to cremation and granting permission to build a crematorium. Our assessment shows that respondents who have had to do with cremation at least once in their life are more likely to agree to cremate their close ones. Paradoxically, the Lviv politicians “are protecting” Lviv residents against the real experience, which, according to data (not speculations), could become a guarantee of a normal attitude to cremation. After all, the fact that less than 5% of the deceased are incinerated in Ukraine every year is probably primarily due not to the special religiosity of Ukrainians, but to the fact that Ukrainians do not have access to appropriate infrastructure.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations