Continuing decline of total population and especially of the labor force, along with its aging, is one of the major challenges to be addressed by the Ukrainian government. If gender- and age-specific labor force participation rates remain constant at the 2016 levels, the labor force in Ukraine is projected to shrink by about 2.9 million people aged 15 years and above by 2030. Even though a larger percentage of seniors aged 65+ years is expected to join the labor force in the future, it will not be enough to make up for decreasing numbers of youth entering the labor force and of working-age population as a whole. As a consequence, the burden on people of working age who supply their labor will gradually increase.

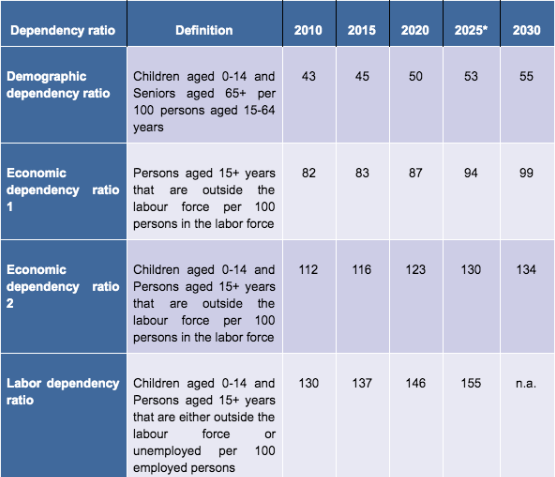

According to the ILO estimates, there will be 155 non-working dependents for every hundred workers in 2024, compared to 137 dependents in 2015 (see Labor Dependency ratio, Table 1). These dependency ratios would be even larger if only formally employed persons, i.e. those who are taxed under the existing tax guidelines, were counted as employed, and informally employed persons were classified as dependents.

Table 1: Dependency ratios in Ukraine, 2000-2030

Source: Demographic dependency ratio – UN World Population Prospects 2017 (population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Population), Labor dependency ratio – ILO modelled estimates November 2018 (ilo.org/ilostat), Economic dependency ratios – author’s calculations based on population from UN World Population Prospects 2017 and labor force participation rates from ILO (https://www.ilo.org/ilostat) by sex and 5-year age groups. Data in 2020-2030 are based on UN population projections (medium variant), with gender- and age-specific labor force participation rates assumed to be constant at the 2016 level. Note: * 2024 is the latest year for Labor dependency ratio provided by the ILO (as of September 2019).

There are three key policy areas for rebalancing demographics and mitigating possible negative economic effects of shrinking and aging population in Ukraine and other countries in the region [38]. These are:

- raising fertility rates and motivating higher female labor force participation rate, with policies that help women combine motherhood with work (maternal and parental leaves, child care services and workplace practices) rather than financial transfers to encourage childbirth;

- improving health of (older) individuals and enabling longer and more productive work lives, with important policies aimed at skills development of an aging workforce, removing incentives of older workers to retire early, and supporting employers who show favorable attitudes toward older workers;

- promoting immigration and discouraging emigration, with effective policies that would make the Ukrainian economy more attractive to potential migrants by improving the business climate and reducing the barriers of the foreign born to formal employment, education and social protection.

Migration

According to the UN data, the total number of migrants from Ukraine has not significantly changed since 1990 and comprised 5.9 million individuals in mid-2017. In all years, Russia is the major country of destination for individuals born in Ukraine, accounting for about 60 percent of the total migrant stock. However, the overwhelming majority of migrants in Russia reported by the UN are in fact Russian nationals born in Ukraine before the USSR dissolution rather than genuine emigrants moving from Ukraine to Russia in the 2000s. The total share of all EU/EFTA, the US and Canada countries is 28 percent of the total stock of migrants from Ukraine in 2017 defined according to the UN approach. Thus, using the Eurostat statistics on permits issued to Ukrainian citizens by EU/EFTA countries, and supplementing it by comparable data from Russia, the US and Canada whenever possible, we embrace the lion’s share of Ukrainian citizens residing and working abroad.

Analysis of the data from Eurostat reveals that the stock of Ukrainian citizens residing in EU/EFTA countries with valid permits in the end of 2017 was 1,188,088 and it is 1.7 times higher than in the end of 2010. The upward trend was driven predominantly by an increase in the number of permits issued for remunerated activities, followed by other reasons and family reasons (Figure 1). Poland is the major EU host country for Ukrainian citizens, accounting for 38 percent of the number of Ukrainians with valid permits of all types in the end of 2017. Other important countries are Italy, Germany, Czechia, Spain, and Portugal, which issued about half of all permits held by Ukrainians in the EU/EFTA area in the end of 2017.

Figure 1: All valid permits held by Ukrainian citizens in EU/EFTA countries on 31 December of each year by reason, 2010-2017

Source: Eurostat (retrieved in July 2019)

It should be noted, that that permanent migrants from Ukraine who have acquired citizenship in the host countries are not captured by statistics on permits used above. According to Eurostat, the total number of Ukrainian citizens who acquired citizenship of some EU/EFTA Member State in 2010-2017 amounts to 144,153 people, with the largest numbers registered in Germany (32,672), Portugal (22,377) and Italy (15,258). Besides, 64,845 Ukrainians were naturalized in the US over the same period (according to the US Department of Homeland Security data). According to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, the number of new Canadian citizens among former Ukrainian nationals in 2012-2017 is 12,324 people. But all these numbers are substantially smaller than 268,896 Ukrainians who acquired citizenship of the Russian Federation during the last three years (2016-2018).

The end-of-year stock of valid permits for remunerated activities issued to Ukrainian citizens in EU/EFTA countries more than doubled since 2010: from 265,344 in 2010 to 574,498 in 2017 (Figure 2). However, the true number of Ukrainians working in EU/EFTA is expected to be much larger than 574,498. This is because at least three categories of migrants are not captured by statistics on permits for remunerated activities: (i) holders of residence permits issued for family or other reasons who can work legally in the host country with no additional permits required; (ii) irregular migrants without the legal right to live and work in the host country; (iii) short-term migrants working abroad up to 3 months, especially after a visa-free travel regime with the Schengen Area countries came into force in June 2017.

According to the data of the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy of Poland, the number of declarations to entrust work to a foreigner issued in Poland to Ukrainian nationals increased from 20,260 in 2007, when the system of declarations was introduced, to 1,714,891 in 2017 (Figure 2). Declarations allow Ukrainians and nationals of some other post-Soviet countries to work in Poland for six months in a year without a work permit or the necessity to conduct a labour market test. Despite the fact that the number of employers’ declarations is much larger than the actual number of seasonal workers for several reasons mentioned in the Polish literature (Kalisz and Chrapek, 2019; Jóźwiak and Piechowska, 2017), there is a clear tendency towards an increasing number of Ukrainian seasonal workers in Poland.

Figure 2: Number of declarations to entrust work to a foreigner issued in Poland to Ukrainian nationals, 2007-2017

Source: Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy of Poland

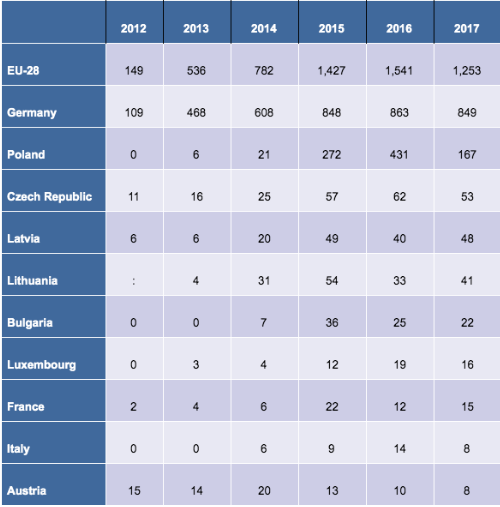

In addition to the overall increase in migration flows from Ukraine, there is also evidence for an increasing number of highly skilled migrants to the EU Member States (Table 2) and to the US (Figure 3).

Table 2: Number of EU Blue Cards issued to Ukrainian nationals by top countries, 2012-2017

Source: Eurostat (retrieved in July 2019). Note: Countries are shown in descending order of the number of Blue Cards issued in 2017.

Figure 3: Number of non-immigrant admissions of Ukrainian nationals to the US with selected types of visas during a given fiscal year, 2010-2017

Source: DHS (retrieved in July 2019)

Key steps that have been taken to promote gender equality:

- The position of the Government Commissioner for Gender Equality Policy was introduced on June 7, 2017 [39]. K. Levchenko was appointed as the first Commissioner in February 2018. This helps implement gender mainstreaming in all central and local executive bodies.

- In 2017 the Ministry of Education and Science launched the antidiscrimination expertise of textbooks used in primary and secondary schools. This will help address the issues of possible discrimination and gender stereotypes among schoolchildren.

- In 2017 the list of banned professions for women [40] was revoked by the order of the Ministry of Health. But references to the list of banned professions are still contained in Article 154 of the Code of Labor Laws. This complicates the effective implementation of the policy.

- In 2017 criminal liability for domestic violence has been introduced and protection of victims of physical, psychological or economic violence in families has been envisaged at the state level.

- Gender-responsive budgeting is being implemented in Ukraine by the Ministry of Finance with support of international organizations. Gender-responsive budgeting is a legal requirement since January 2019.

- In January 2019 the new state social program “Municipal nanny” came into force after being approved by the Government in May 2018 within the National Action Plan for the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child up to 2021. Its idea is to provide financial support to parents to fund care services for children up to three years. The policy can potentially increase the employment rate of mothers, but due to a fairly small amount of support it is likely to be effective only in small towns or villages where the salary is low.

You can find out more about the ‘White Paper on Reforms 2019’ project and other chapters of the book at this link

[38] See more in Bussolo M., J Koeetle, and E. Sinnott (2015) Golden Aging: Prospects for Healthy, Active, and Prosperous Aging in Europe and Central Asia, Washington DC: World Bank

[39] The main tasks of the Commissioner include coordination of the work of ministries, other central and local executive bodies to ensure equal rights and opportunities for women and men, conducting the monitoring of the accounting by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine the principle of gender equality, assistance in developing state programs on gender equality and cooperation with international organizations and civil society.

[40] The List of 458 hard, dangerous and harmful jobs in Ukraine was adopted by the Order of the Ministry of Health # 256 of 29.12.1993. It banned women’s employment at certain jobs, including driving vehicles with more than 14 passenger seats, tractors and other agricultural vehicles, sea and river boats, or be employed at a number of industrial and agricultural positions

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations