The optimal policy solution would be not to lower military expenditure in 2016 (whether in real or in nominal terms) and shift the debate instead to how much they should be increased to efficiently allocate the limited government resources and to ensure the country’s security. Practically all other categories of government spending are much less efficient and, consequently, provide much more room for budget cuts with little negative consequence.

The reports [1] in Ukrainian media on the ongoing budget process, as well as documents leaked out of the government [2], show the plans to cut military spending in 2016 in real terms, by leaving it at the same nominal level as it was in 2015. This column argues that such policy measure is a bad idea and would hurt both the effectiveness of government spending and the security of the country.

Returns on military expenditure

Omitting the military assets left over from the Soviet Union (arms, ammo etc.), Ukraine has spent 580.5 billion UAH on its defense needs in 1993-2014, in constant 2010 prices (thus comparable over the years). It is thanks to these expenditures that the country has found itself in possession of an army, that – with a huge support from civilian citizens [3] – was capable of successfully limiting the Russian occupation to Crimea and part of Donbas.

To calculate the ‘returns’ on these expenditures, let us take a look at how they correlate with various estimates of GDP, that would have been lost in case the Russian invasion was more successful.

In 2014 Ukraine’s GDP in constant 2010 prices was 1062.8 billion UAH. Let us assume three possible scenarios of how much territory Russia would have conquered, had Ukrainian resistance been too weak to stop the aggressor:

- occupation of Southern and Eastern regions;

- occupation of Southern, Eastern and Central regions (leaving only Western Ukraine unoccupied);

- occupation of the entire country.

Without the occupied Crimea and parts of Donbas, the Southern and Eastern regions of Ukraine produce 43% of the country’s GDP. In 2014 this amounted to 457 billion UAH in constant 2010 prices – or 80% of all Ukrainian military expenditures throughout the country’s lifetime. If we suppose that, without strong resistance, the Russians would have occupied the Southern and Eastern regions by summer 2014, than all military expenditures ever made by independent Ukraine have fully paid for themselves.

In the second scenario 81.5% of the country’s GDP would have been lost to the invader, or 866 billion constant 2010 UAH – 150% of accumulated military expenditures. In this case, since 2014 the entire Ukrainian military expenditures throughout the country’s lifetime have already returned around 175% of their value.

In the third scenario 100% of GDP would have been lost, or 183% of accumulated military expenditures – which makes the returns on them almost 200% of their value.

This calculation shows that while an existential threat to the country exists, the rate of return on military expenditure in terms of GDP-producing territory that it helps protect from occupation is huge – close to 100% per year in 2014-2015. This makes military spending by far the most efficient category among government expenditures in Ukraine. With all the other categories being inefficient, bloated and routinely embezzled, any budget cuts should be conducted in them, not in military expenditures.

Foreign experience

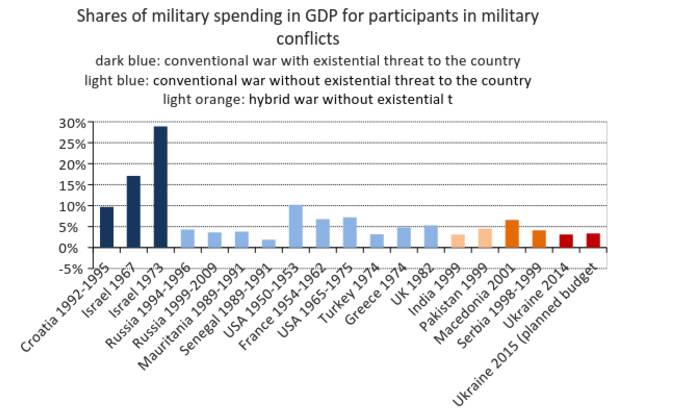

Sources: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Central Bureau of Statistics of Israel, Ukrainian Treasury

Now, let us look at the current level of Ukrainian military spending in light of other countries’ experience in similar conflicts.

Due to the fact that the typology of the military conflict in Ukraine is complex, data on military spending for four types of conflicts has been gathered:

- Regular conventional wars in which the country that the data on spending is given for was facing an existential threat (a threat to the country’s existence). Average yearly level of spending: 18.6% of GDP.

- Regular conventional wars without an existential threat to the country. Average yearly level of spending: 5.1% of GDP.

- Hybrid wars (executed unofficially through parties in internal conflicts) without an existential threat to the country. Average yearly level of spending: 3.8% of GDP.

- Hybrid wars with an existential threat to the country. Average yearly level of spending: 5.4% of GDP.

While this typology is somewhat artificial and conventional (neither does it draw on deep studies on classification of military conflicts) it is useful in analyzing the war in Ukraine due to the fact that it can fit any of the four types of conflicts presented. Ukraine has clearly won the purely hybrid phase of the war, forcing Russia to intervene directly and thus turn the conflict into a conventional international war. The presence of existential threat can also be debated (depending on one’s assumptions about Kremlin’s plans), though arguably it is much more probable that an existential threat to Ukraine is in fact present.

In 2014 military expenditures in Ukraine have constituted 3.1% of GDP [4], while the budget plan for 2015 is 3.35% of GDP [5]. This is lower than the average level of spending for participants in any of the four types of conflicts specified above. Thus, based on international experience in the second half of 20-th and the beginning of 21-st century, Ukraine needs to raise its military spending by 1-2% of GDP, not lower it.

For the 2016 the Ministry of Defense has asked for its budget to be raised to 3.8% of GDP. If this request is accommodated and the real levels of spending are preserved for the National Guard and the border guards service (which, together with the armed forces, roughly constitute the military force of the country), the overall level of military spending in Ukraine would rise from 3.35% of GDP to 4.5% of GDP. This would bring them close to average levels of military spending by countries engaged in similar conflicts in the second half of 20-th – beginning of 21-st centuries.

Conclusions

- Military expenditures are one of the most (probably, the most) efficient categories of government spending in Ukraine in terms of their impact. The entire cumulative real military spending of Ukraine throughout its independent existence has already more than fully paid for itself, with possible yearly returns varying between 100% and 200%. It is important to note though that this does not mean that the military is free of corruption and inefficiency (ample evidence points to the contrary and there is likely large room for increasing the efficiency of spending), only that in the situation of existential military threat to the country the expenditures on defense pay off very well.

- Current level of military spending is still low if compared to other countries that throughout their recent history have found themselves in similar circumstances. International experience suggests that additional 1-2% of GDP should be allocated to military spending.

Based on these conclusions, the optimal policy solution would be not to lower military expenditure in 2016 (whether in real or in nominal terms) and shift the debate instead to how much they should be increased to efficiently allocate the limited government resources and to ensure the country’s security. Practically all other categories of government spending are much less efficient and, consequently, provide much more room for budget cuts with little negative consequence.

Notes

[1] http://www.rbc.ua/ukr/analytics/nalogovaya-reforma-poslednie-raschety-mvf-1446840894.html

[2] http://www.epravda.com.ua/publications/2015/11/6/566195/

[3] https://www.facebook.com/paul.kukhta/posts/943281685723611

[4] SIPRI data

[5] Current budget plans for the Ministry of Defense, National Guard and border guard service, IMF 2015 GDP forecast

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations