In modern Ukraine, given the economic crisis, external military aggression, weakness and instability of democratic institutions and practices, the prevalence of a culture of poverty is not just a negative social phenomenon, but a long-term danger to the survival and democratic development of the country.

Full version of the article is available at Euromaidan Press.

«In a broad sense, we can talk about the culture of poverty, which becomes a way of life for a large group of people and acquires signs of heredity. The formation of such a culture is facilitated by both structural factors and subjective feelings of people», – says the study of the culture of poverty in Ukraine conducted by the Association of Middle East Studies and Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU) with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. In the qualitative study of the poor that Euromaidanpress summarizes below, researchers tried to find out how poor people see themselves, their place in the society and the world around them; how people construct “we” and “them” social groups. The researchers also discussed poverty-coping strategies of project participants. These strategies are reliance on relatives and short-term borrowing which cannot lift a person out of poverty.

45 people who can be characterized as poor — they receive some social assistance or a subsidy — and 15 experts (social workers) who can also be characterized as poor were surveyed.

In addition to the survey, they conducted 16 in-depth interviews and six focus groups (of them, two with social workers). The study took place in Skadovsk and Chaplynka, two medium-sized towns in Kherson Oblast.

The study participants differ by sex, age, and family status. People in Kherson Oblast were likely to become abruptly poor after the annexation of Crimea, which ruined their usual economic ties and earning opportunities.

The main conclusions from the study are as follows

The self-evaluation of participants as ‘poor,’ ‘lower-middle-income,’ ‘middle-income,’ etc. is disconnected from actual revenues.

The majority of project participants believe they have “middle-income.” At the same time, they may change their self-defined category during the interview. This means they don’t have a clear understanding of their relative position in society.

Most project participants do not talk about their poverty, rather, they refer to abstract “poorness,” thus avoiding the real problem. However, this does not prevent them from complaining about a lack of resources and wanting to receive social assistance.

Study participants tend to underreport their income and exaggerate expenditures. This may happen because they do not report sporadic or unofficial earnings and are feel pressured by expenditures.

Participants don’t have a clear understanding of the structure of Ukrainian society – they overestimate the shares of both “poor” and “rich” and struggle to define the “middle class.”

Social classes are mostly defined via accessible consumption, i.e. the poor have to economize on everything, the “middle class” can have everything they need, while the rich “don’t care about money.”

They make a distinction between the poor who cannot work due to health reasons and those who are poor because of “their own fault,” e.g. an addiction.

The rich are also divided into broad groups of those who received their wealth by fraud and those who worked hard for it.

Only a few study participants named systemic causes of poverty, such as the absence of the judiciary and labor unions who would protect the rights of workers. Some blame unemployment on the collapse of Soviet factories.

All but one study participant could not clearly define their responsibilities at work. Nevertheless, all of them stated that they would like to have a higher salary (on average three times higher).

Those who have experience of working abroad report that there they worked much harder. However, they did not bring that work ethics to Ukraine – rather, at home they relax and spend money earned abroad. Generally, many project participants opt for quick sporadic earnings, mostly in the informal sector. Although they dream about a stable high-paying job, they are not trying to find one.

Respondents feel detached from society (and also do not participate in civic activities) since in the times of hardship they rely only on relatives or short-term credit (less than one month). This is the only coping strategy used by study participants. Experts who participated in the study admit that sometimes poor families can buy expensive things, such as a plasma TV or a smartphone while they economize on food. This is a reflection of the generally low financial literacy of Ukrainians. When asked how they would spend additional income, the majority of study participants indicated consumption rather than investment, supporting this conclusion.

This short-sightedness perhaps explains political views of study participants – they hope that someone (the president?) will restore ‘law and order’ and will provide them with a stable workplace and low communal tariffs. People with this level of understanding of institutions and social processes can easily fall victim to various political manipulations.

Below we elaborate on these conclusions.

The majority are poor but honest, minority are rich but thieves and we are “close to the middle”

When asked to estimate the proportion of different social groups in Ukraine, project participants said that the majority of Ukrainians are poor. On average, respondents think that the “poor” constitute 61.5% of Ukrainians, the “middle-income” – 26.5%, and the “rich” – 11.5%.

According to the State Statistics Agency survey, about 40% of Ukrainians economize on food and clothing, 11% could make savings, and about 50% had enough money for everything but did not save. Thus, study participants clearly overestimate the share of poor in Ukraine – perhaps because they made their judgement based on their social bubble.

However, not only is the proportion of social groups of importance, but also the characteristics that participants attributed to various social groups.

The poor

First of all, interviewees describe poverty as deprivation — a partial or complete inability to meet basic needs such as food and utility payments. Other basic needs are considered not covered at all. Many participants consider poverty as not only financial insolvency but also lack of time for moral and cultural self-realization:

“Yes, I consider myself poor. Because my whole way of life converges to the fact that I have an alarm clock set to 5:30, I get up, go to work. The work is very hard, because no one wants to work […] Fatigue is very strong. I come home, go to the store to buy some food, and while I cook to eat, and basically.. And the whole way of life converges only to this – cooking, watching the news and.. routine.

Another specific point in the descriptions of poverty is that respondents often associate it with honesty:

“[There are] many people who can’t work. Because people get sick, can’t leave their home, can’t find a job. They can’t even buy milk. Because they spend, only as far as they are honest, they pay for utilities, pay for everything, and there is nothing left.

…

But such tariffs, especially in winter without subsidies, people who work honestly simply can’t afford…”

People subjectively divide poverty into two models: socially acceptable and socially condemned.

Socially acceptable is a model of poverty where people for objective reasons are deprived of the opportunity to earn (old age, weakness, disability, taking care of children, etc.) but keep their home and themselves in order. This is the Soviet model of socially approved poverty, so-called “poor but clean.” Instead, the second, negative, image of poverty is associated with the presence of antisocial habits such as alcohol addiction.

Middle class

Descriptions of the “middle class” are less detailed, contain much fewer clarifications and explanations, examples, and illustrations. Explanations of the “middle class” lead to the conclusion that people describe a state close to their own. For most respondents, being “in the middle” means being like everyone else. Therefore, the typical positive image of the “middle class” as a family having their own house, transport, and sufficient income is not common. Instead “middle class” is a form of self-appeasement. Many people can also consider themselves “close to the middle” and “poor” at the same time.

Middle-income is when it is already possible to put a fence and make some repairs. It is middle level. When you can buy something that you like, well, not always, but at least occasionally. Eat more or less good quality food and afford healthcare.

Additionally, “average” is usually the result of “collective effort” – mostly family ties. The middle class is considered mainly in the context of entrepreneurial activity. However, it is primarily a small business that is unstable and suffers from changes in economic conditions.

Rich

In the descriptions of the imaginary “rich,” respondents cite the same standard set of goods and services that was present in characteristics of the “poor” and “average.” The difference is that the imaginary rich do not experience restrictions on access to the goods; they can afford to spend money without counting it. An additional important factor, which is rarely encountered in the descriptions of the middle class, is the opportunity to receive a good education in Ukraine or abroad.

A negative perception appears in the description of the rich. Wealth is seen as a manifestation of greed, thirst for unlimited consumption, disrespect for others, there are motives of immorality or dishonest earnings. Unequivocally negative descriptions apply to the “distant” rich (political elite, oligarchs, MPs, etc.) – those whom respondents can’t know personally, and only know as a media-image.

Rich? There is an opportunity to study, it is possible to study abroad, yes, and also to receive expensive, high-quality healthcare if necessary. An opportunity to buy expensive clothes and equipment as well […] They have deposits, are socially protected, regardless of the situation in the country, preferably in dollar currency…

…

We now see, both on television and around us, very rich people, who do not even hide their wealth, and we see that this wealth is not earned in an honest way.

…

[Rich are] people who in my opinion are the old system, people who are already greedy and should leave … (laughs). You know, people who are really, well, arseholes.

Describing the rich, some respondents are aware of not having personal knowledge and experience about what they say:

It’s hard for me to say something because there are no rich people in my social circle.

Thus respondents have a rather vague idea of the social structure of Ukrainian society. Descriptions of different segments of the population are mostly based on assessing the availability of certain basic goods that can be purchased, rather than education, social and political roles, the possibility to not only buy personal goods but also to fund social or other projects, etc.

The reluctance to classify oneself as “poor” is evident even if respondents have obviously low income. They try to prove that they are not poor but average, “like everyone else.” The image of the “poor honest man” is the least negative and the most common. Images of other groups are projections of “improved poverty,” which in fact does not go beyond the construct of the “well-fed life” and is not associated with the opportunity for self-realization, access to cultural heritage.

Ukrainians tend to underestimate their income and exaggerate expenses

While “poor but honest” is the most positive image and wealth is considered as something desirable but unreachable in an honest way, it is not a surprise that respondents tend to underestimate their income. On average, reported spending is 1/3 higher than earnings.

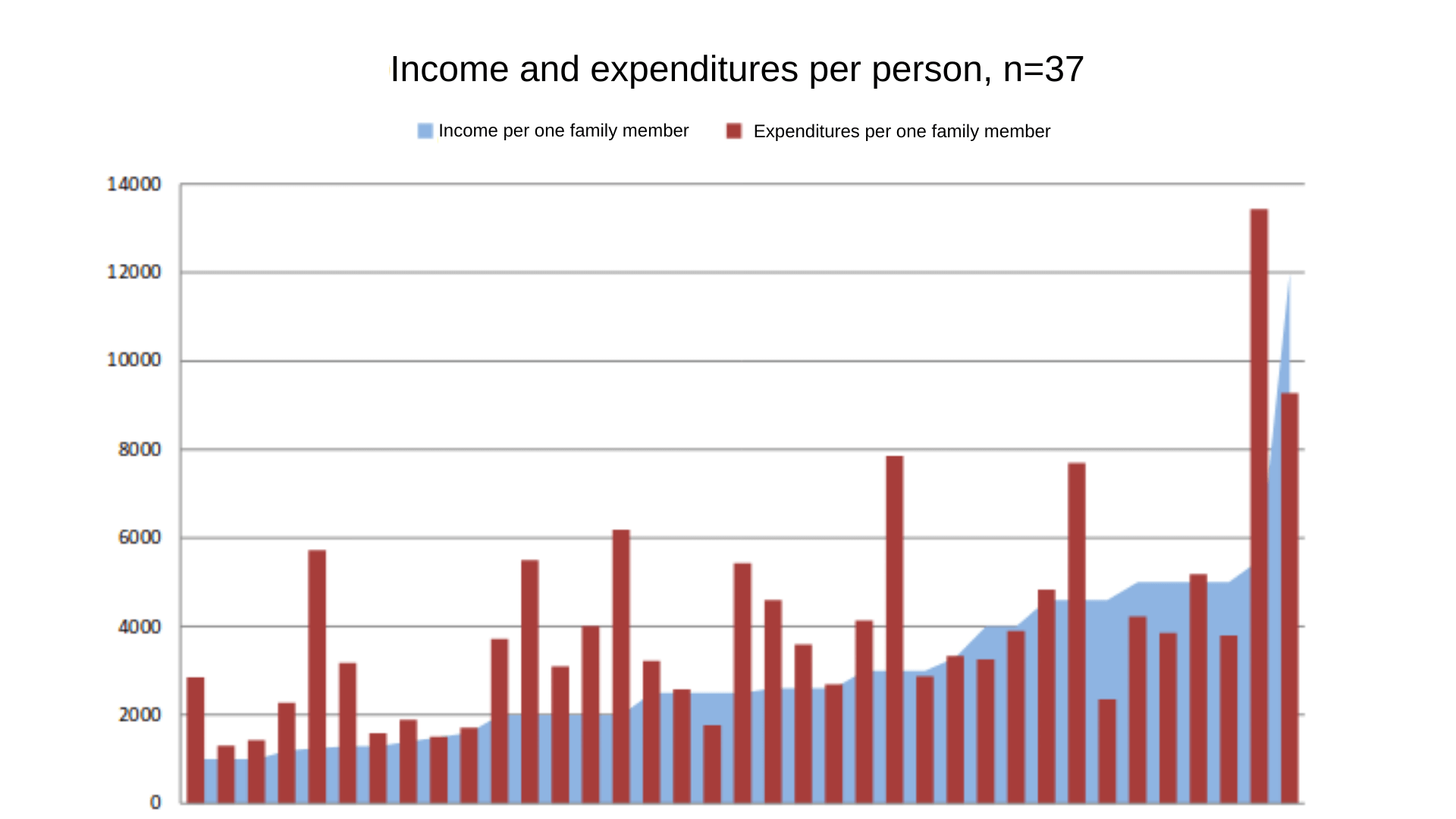

Figure 1.

Source: the study of the culture of poverty in Ukraine conducted by the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU). Translated by Euromaidanpress.

Thus, 57% of interviewees report higher spendings than income. The study reveals that it’s common to report only official and regular cash benefits (salary, pension, regular government support etc.) as income. All other sources of income (temporary earnings, remittances, one-time payments, seasonal income) are mostly not taken into account when estimating the family budget. That leads to the considerable underestimation of one’s well-being.

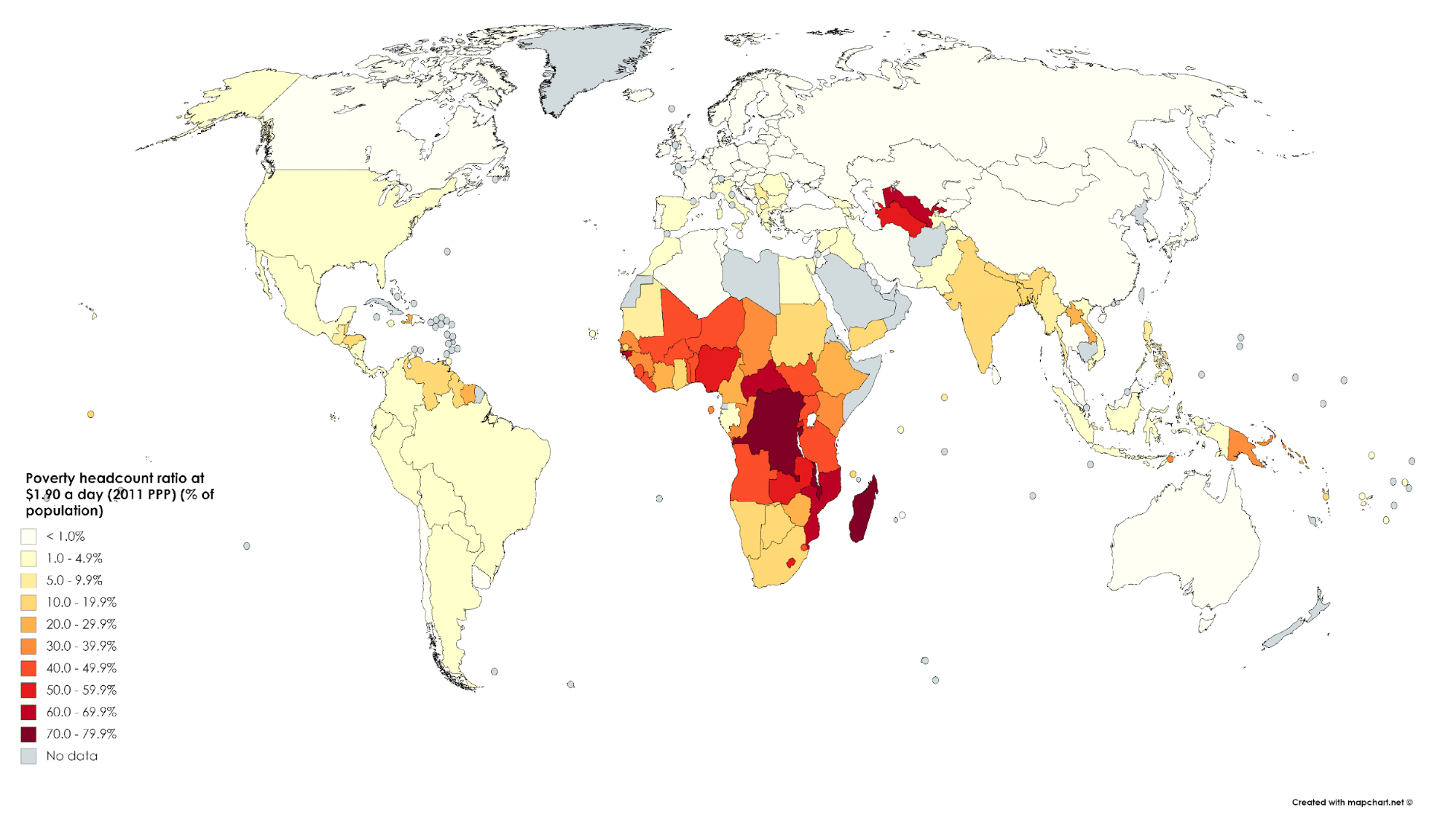

More evidence of Ukrainians self-underestimating their income lies in the fact that 25% of respondents considered themselves belonging to the group of “poor people in poor countries.” In reality, these are people living on less than $1.90 a day. Ukraine has a negligible share of such people.

Figure 2. Poverty in the world

Source: wikipedia

Causes of poverty and strategies to overcome it

The main causes of poverty named by respondents are either the inability to work (‘positive poverty’) or unwillingness to work (‘negative poverty’). However, we can derive from the answers that in many cases these people do not try to organize their work efficiently (let alone gain some additional knowledge) nor prudently use the funds which they have.

Structural factors also affect the state of poverty in society. In particular, the policy of deindustrialization that followed inconsistent market liberalization without Ukraine’s adaptation to the global market resulted in the closure of the largest Soviet-era enterprises and re-profiling the Ukrainian economy to outstaffing and export of raw materials. Many people lost jobs and failed to adapt to the new reality. As a result, nostalgia for Soviet stability, albeit with fewer opportunities, is often mentioned in the respondents’ answers.

Some interviewees mention a lack of financial planning skills, consumerism, and absence of savings even among those who have a higher income as a cause of poverty. The situation is aggravated by alcohol addiction.

“The youth work and drink. Do you understand? Well, you can see it. Guys just have arrived from Poland with earnings. And every day, every day there is a bottle on their table.

…

I can really see that people don’t drink or smoke, but they can’t really manage money. They waste money for some phones and games there.”

Low efficiency of work was key for many answers, either as the self-description of the respondents or as the description of others’ work.

Most respondents could not detail their functionality at work. Neither do they have a clear work plan. Activities performed by an employee during working hours are often far from their job functions. It is also common for people to switch to unfamiliar tasks which reduces the efficiency of their work. Poor organization of work and performance of unusual functions results in a feeling of unpleasant fatigue and dissatisfaction.

Those who worked abroad can compare the organization of work at home and abroad (mostly in Poland). They confirm that “you need to work hard there.” However, returning home, people tend to relax after hard work in another country.

“…I know, our neighbor, he is a young man. The first time working abroad was a shock for him, because it really was necessary for him to work hard, unlike here… Well, yes, if they give money, they require quality of work…. And eight or six hours, you must not be distracted, not to go for smoke breaks. Unlike our miners, who say: ‘I go there to the mining route to work for an hour, then we sit there for another hour, we smoke straight on the route, yes, although there is gas, methane, and then we sleep for an hour, we make coal yet another hour, and an hour back to go. Here it is.’ This is impossible in Europe.”

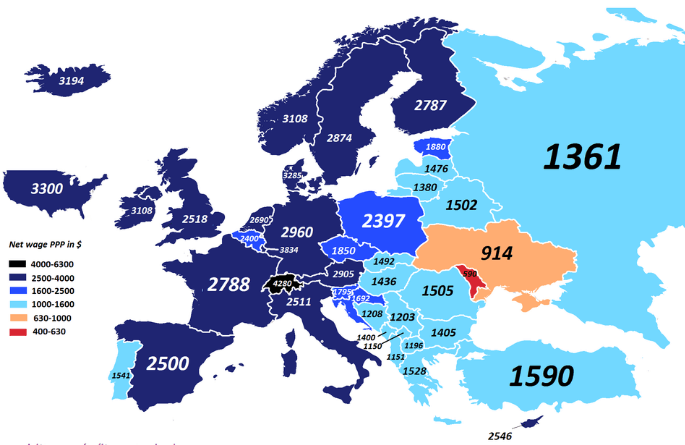

At the same time, all respondents think that employers have to pay more for their work despite their low productivity. On average, people think their salary should be 3.2 times higher (between 1.3 to 12 times). Only one of 32 respondents believed that his salary was just right. The average assumption of 3.2 times higher would be more than the average salary in Poland and a German level of life if salary adjusted to Ukrainian prices.

Simultaneously, all respondents think that employers have to pay more for their work despite their low productivity. On average, people think their salary should be 3.2 times higher (between 1.3 to 12 times). Only one of 32 respondents believed that his salary was just right. The average assumption of 3.2 times higher would be more than average salary in Poland and a German level of life if salary adjusted to Ukrainain prices.

At the same time, people simply don’t have time for financial literacy and rethinking their way of life. To have an more or less acceptable quality of life, many have to work on two-three jobs or do additional work themselves, such as repairing the house or car or small farming at a country house.

Consequently, people do not have time and extra strength to engage in the life of their local community or local politics, let alone self-education or startups. Even something as simple as traveling to Poland for work or to change their profession is sometimes unaffordable – many people do not have money for a passport and tickets.

The majority of respondents reproduce the survival practices of Soviet society.

The culture of deficit remained, albeit it is no more a shortage of goods but a shortage of money. Accordingly, the practice is unchanged – the person but “rummages” as a predator in a forest. From time to time she manages to seize something and to live a day more. People use to describe their style of employment as “today here, tomorrow there,” “a little here, a little there,” “we are running around” and so on.

This way of life develops shortsightedness, i.e. a person thinks only for one day or a few days rather than years ahead and does not have a clear vision for the future. Not having a plan for life causes frustration and chronic dissatisfaction.

The authors of the study stress that in order to solve the problem of poverty in Ukraine, simply giving people more money or more work is not enough. The culture and subjective factors remain as important as structural conditions, at the very least. The example of labor migrants to Poland is the best demonstration of this. Remittances transferred to Ukraine do not often turn into profitable investments or self-improvement. They rather convert to excessively huge houses that raise people’s self-esteem but are expensive to maintain, or extra-expensive TVs, computers, and phones.

Annex. Is Ukraine poor as a country?

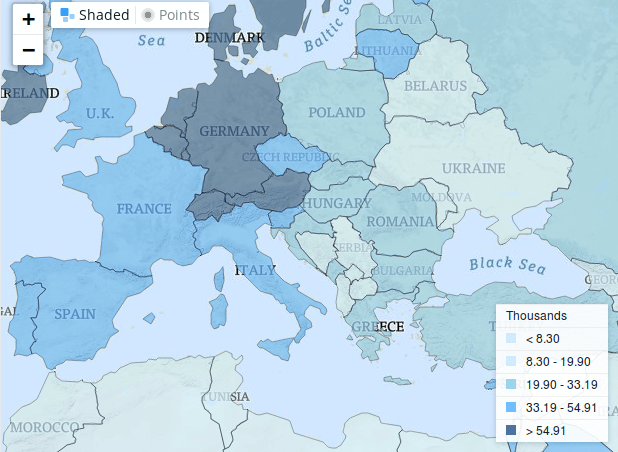

GDP per capita, PPP, 2019, thousands of US$. Ukrainian GDP per capita is 12,810, much lower than Polish 33,086, German 53,815 or even Belarusian 19,149. Source: World Bank

Net average monthly salary adjusted for living costs.

While Switzerland has an average monthly salary of €4600 and Ukraine of €400, the numbers become less divergent if adjusted for higher prices in Switzerland and lower in Ukraine (€4200 and €900 respectively). But still, the average Ukrainian can purchase 4.5 times fewer goods than the average Swiss citizen or 3 times fewer than the average German. Source: reddit.com, created by lieverturksdanpaaps

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations