Why should producer make a movie, develop software or write books, if the exclusive rights of his work can be stolen, and no one will pay for it? Hence, local film producers decide to export their films abroad instead of distributing them in the domestic country with weak intellectual property rights protection.

What are the cultural and creative industries (CCI)?

With the development of technology and the digital revolution, the creative and knowledge-based industries became an essential part of the world economy. According to UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), creative sectors include production and sales of films, design, art, crafts, books, paintings, festivals, music, drawings, digital animation, and video games. In 2013, the total amount of produced cultural and creative goods was 3% of world GDP or 2.3 trillion US dollars.

Just like the manufacturing, the CCI (cultural and creative industries) sector generates substantial revenues also through trade. UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) reports that in 2012, the global trade market for creative goods and services amounted to $547 billion, which is a quarter of the worldwide production of CCI, in the ballpark of Swedish GDP. According to UNESCO, the value of trade in creative goods and services doubled from 2002 to 2011. But, this is a less significant growth compared to the threefold increase in the global trade in all goods (WTO).

How are CCI connected with digitalization and piracy?

Cultural and creative industries also drive the online economy with $200 billion global digital sales in 2013, and boosting the $530 billion market of digital devices. Besides, digital cultural goods generated $66 billion of B2C sales and $21.7 billion of advertising revenue for free streaming websites and online media.

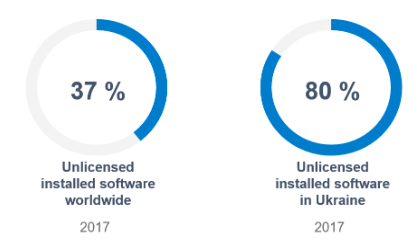

At the same time, the development of the creative economy has been accompanied by pervasive digital piracy. According to the Business Software Alliance, in 2017, 37% of software installed worldwide on personal computers is still unlicensed generating $46.3 billion of commercial losses globally. Unfortunately, Ukraine ranked among TOP-25 countries with the highest digital piracy level with four out of five (80%) software components on Ukrainian computers installed illegally.

Figure 1. Piracy level for world and Ukraine in 2017 by Business Software Alliance (BSA)

How piracy affects CCI’ production?

Economic theory predicts that piracy should hurt CCI development hitting the revenues of copyright owners who have invested time and money in producing films, sound recordings, books, and computer software. It is estimated that piracy costs the US music companies $12.5 billion of revenues, and the US government $422 million in taxes annually (Siwek 2007). However, piracy can have a positive impact on complementary industries. For instance, music piracy increases demand for audio equipment, boosting, for example, iPod sales by 12% (Leung 2015). Thus, audio equipment manufacturers have an increased demand for their products because the lower costs on creative products (for example “zero”) give more reserves for spending on hardware products.

The piracy effect is even more nuanced within the film industry, because here the time factor matters. After the first viewing, the film becomes less attractive. Repeated reviewing of the film does not bring the same level of utility as it was at the very first time. Thus, the illegal distribution of a movie before the official premiere reduces its revenue from the box office by 19.1% compared to one which is leaked to the network after (according to Ma, et al. 2014).

How piracy affects CCI’ trade?

When we go from production to trade, the impact of digital piracy becomes contradictory. Ndubuisi and Foster-McGregor (2018) found that intellectual property rights (IPR) protection is trade-related and the level of IPR protection in the domestic country matters more for exporters than importers. Lionetti and Patuelli (2009) analysed trade in CCI using a gravity model of trade and data from UNCTAD. They discovered that digital piracy decreases trade in the Music industry, but increases — in the Film and New Media industries. These results are counterintuitive, and thus, I re-estimated the findings using the most recent UNCTAD data.

First of all, UNCTAD offers the following product classification. The Film industry composes from video, music, television, Internet, and satellite rights, box-office sales, and merchandising. On the other hand, Audiovisuals industry includes only CDs, DVDs, tapes, etc., which is a material storage medium.

However, New Media products should be defined accurately because official definition “recorded media for the sound/image, and video games” does not cover them well enough. New Media is a creative product described as a digitalized form of creative content such as cartoons, software, and interactive products such as video games. But, sometimes, it is hard to distinguish a creative product between New Media and Film industries. For instance, a digitalized cartoon film is a part of both productions at the same time.

Thus, using the gravity model of trade and capturing spatial autocorrelation by the eigenvector spatial filtering technique, I re-estimate the study by Lionetti and Patuelli (2009). For this, I used a panel of international trade in creative goods for 2002-2015 between 26 countries with a different level of piracy and trade. Thus, the key differences with Lionetti and Patuelli (2009) is that I used recent data, a consistent digital piracy indicator, and more empirical specifications. I found that almost all coefficients indicate a negative impact of digital piracy in both import and export countries on the bilateral international trade in Film, Audiovisuals, and New Media industries. Despite that, one factor out of six has a consistently positive sign, which is the impact of digital piracy in the domestic country on exports in the Film industry.

Conclusions

So, substantially digital piracy is bad for international trade in CCI. However, internal piracy positively affects exports in the Film industry. Previously, Lionetti and Patuelli (2009) suggested that we should treat piracy as an advertisement for the legal source of distribution of the Film industry. This may work for imports, but hardly explains a positive effect on exports. Several years after, Lobato (2012) argue that the government closes eyes on illegal trade and regards it as a driver of tax revenue and employment. While this is a more logical explanation than previous, it does not cover my findings. Thus, I explain increasing trade through a local-foreign substitution effect. It means that the domestic film producers observe a high level of piracy in the domestic country and decide to export their production abroad, which directly increases trade between countries.

But the question remains open, why the positive effect exists only for the Film industry and not for others. Sure, it can be because there exists a high threshold for entry into the Film industry or that the data from UNCTAD do not include electronic trade in the official statistics, which is sensitive because of the rising of streaming companies such as Netflix, Amazon, etc. However, despite the negative impact of piracy, its level in the world is falling, so the trade in cultural goods should grow, except for the Film industry. Thus, maybe trade in films falls because more and more people watch movies on Netflix? And it is not the effect of piracy but rising a new epoch of home streaming cinema after the dying box-offices’ era.

Works Cited

-

Lionetti, S., and R. Patuelli. 2009. “Trading Cultural Goods in the Era of Digital Piracy.” Rimini Centre for Economic Analysis. Working Paper 40-09: 31.

-

Leung, T. 2015. “Music piracy: Bad for record sales but good for the iPod?” Information Economics and Policy 31: 1-12.

-

Lobato, R. 2012. “A sideways view of the film economy in an age of digital piracy.” NECSUS. European Journal of Media Studies. (Amsterdam University Press) 1 (1): 85-97.

-

Ma, L., A. L. Montgomery, P. V. Singh, and M. D. Smith. 2014. “An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Pre-Release Movie Piracy on Box Office Revenue.” Information Systems Research 25 (3): 590-603.

-

Ndubuisi, G., and N. Foster-McGregor. 2018. “Domestic intellectual property rights protection and the margins of bilateral exports.” UNU-MERIT Working Papers 035: 34.

-

Siwek, S. 2007. “The true cost of sound recording piracy to the U.S. economy.” Institute for Policy Innovation: Policy Report 188: 28.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations