The global economy is going into a recession. This is a bad time for countries like Ukraine: exports decline, tax revenues shrink, the currency devalues, the cost of borrowing soars, access to international credit falls. Is it a good time for the Ukrainian government to default on its debt? The short answer is “no”.

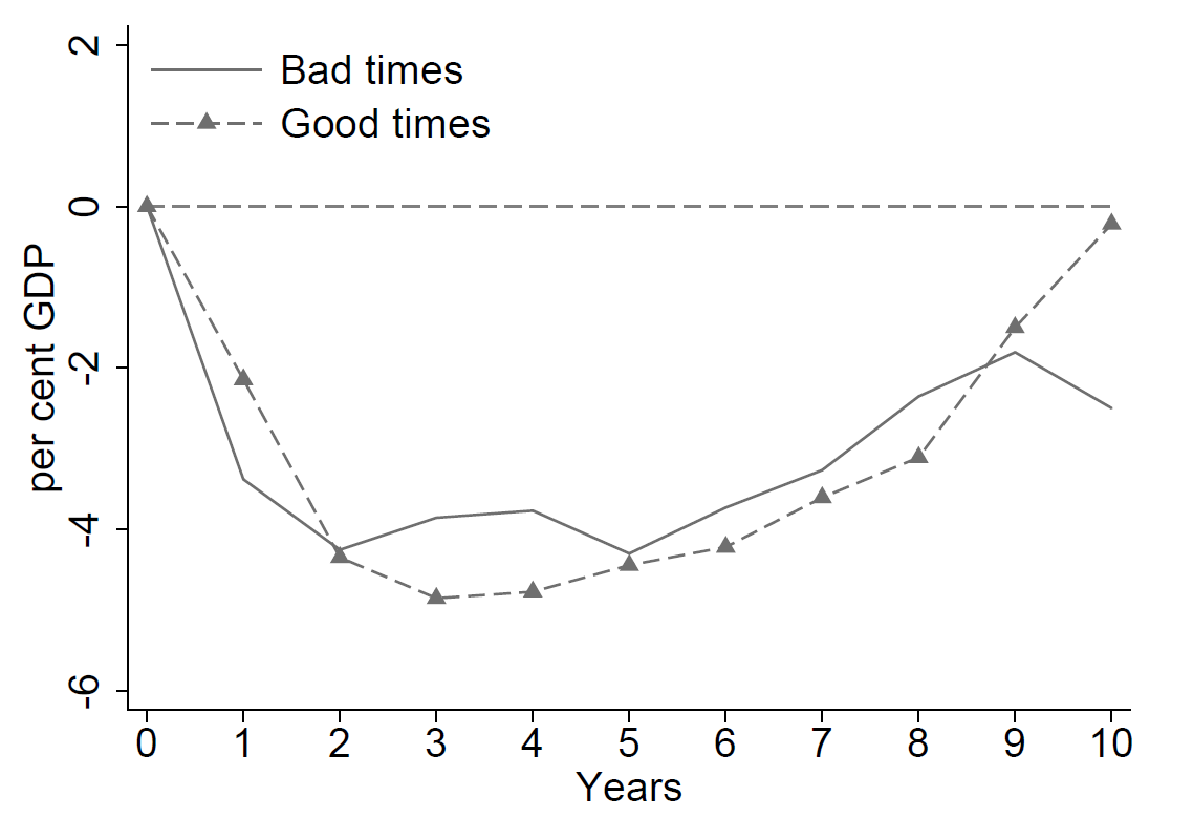

Obviously, sovereign defaults are complex events and the cost of defaults varies across times and countries, but certain patterns are clear in the data. IMF economists Borensztein and Panizza (2009) consider and document several economic costs of default: output falls, trade falls, almost full exclusion from capital markets, borrowing costs increase, risks of a banking crisis increase. A recent study by two economists at the University of Bonn provides a sense of magnitudes for the decline of output: after a default, GDP declines by approximately 5 percent and stays depressed for many years (Figure 1). Ukraine badly needs economic growth, and a 5 percent fall is the last thing the economy needs now.

Figure 1. Cumulative decline in GDP in response to a sovereign default.

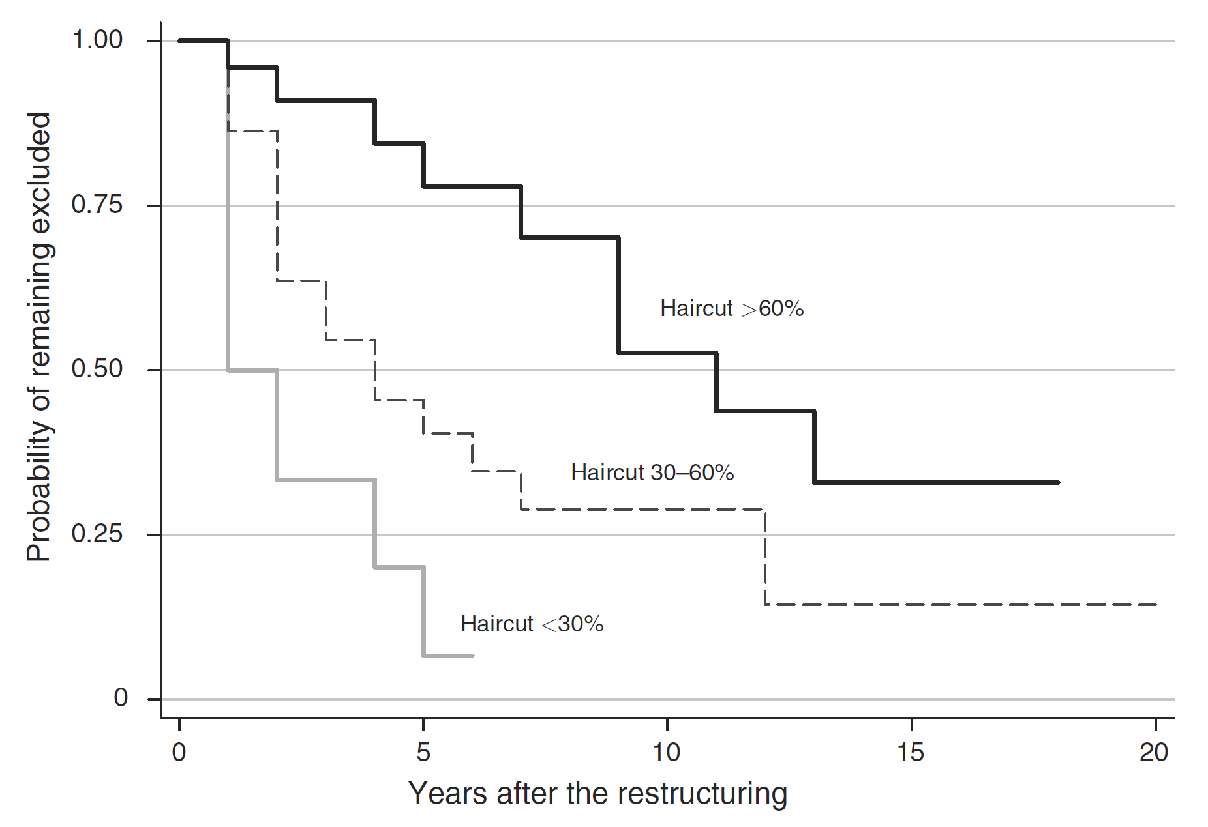

Cruces and Trebesch (2013) provide recent estimates for how long a defaulting country is excluded from the global capital market. Figure 2 based on this study shows that the larger is the size of default (or “haircut”, that is the share of the debt on which a country defaults), the longer is the period of exclusion. The average exclusion time is about 5 years. Whether Ukraine can get access faster is an open question but it is hard to imagine that, with a materially important default (and insignificant defaults make no sense!), the process will take less than two years.

Figure 2. Probability of staying excluded from global capital markets

Borensztein and Panizza also estimate political costs of defaults: a 16 percent decrease in support of the ruling party in the first election after a default; a 50 percent increase in the probability of replacing the head of the executive; a 33 percent increase in the probability of replacing the minister of finance or the head of the central bank. In other words, a default can mean the end of political careers for those who engineer it.

These are averages, however, and the Ukrainian context can make default calculus a lot more unpleasant.

First, a lot of Ukraine’s debt is to other governments (e.g., U.S. government) or semi-government bodies (the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, etc.). How can Ukraine expect to get help (including military equipment) from its partners if Ukraine fails to honor its current obligations to them?

Second, due to the coronavirus crisis, Ukraine is going to experience a big economic downturn. Because tax revenues will fall, the government will have to borrow to maintain the current level of spending, which includes spending on defense and healthcare. Of course, the government can cut its spending to balance its fiscal budget but the Great Depression and scores of other historical examples (most recently Greece) suggests that doing so in a weak economy is suicidal. Hence, the government should have access to capital markets to borrow funds and cover short-term loss of tax revenue. A default will sever this access.

Third, Ukraine has to pay for the war with Russia. Few (if any) countries defaulted while being at war. After all, wars are expensive and, to keep the economy running, governments have to borrow to pay for personnel, tanks, guns, etc. How can Ukraine afford its military expenses if it does not have access to global capital markets?

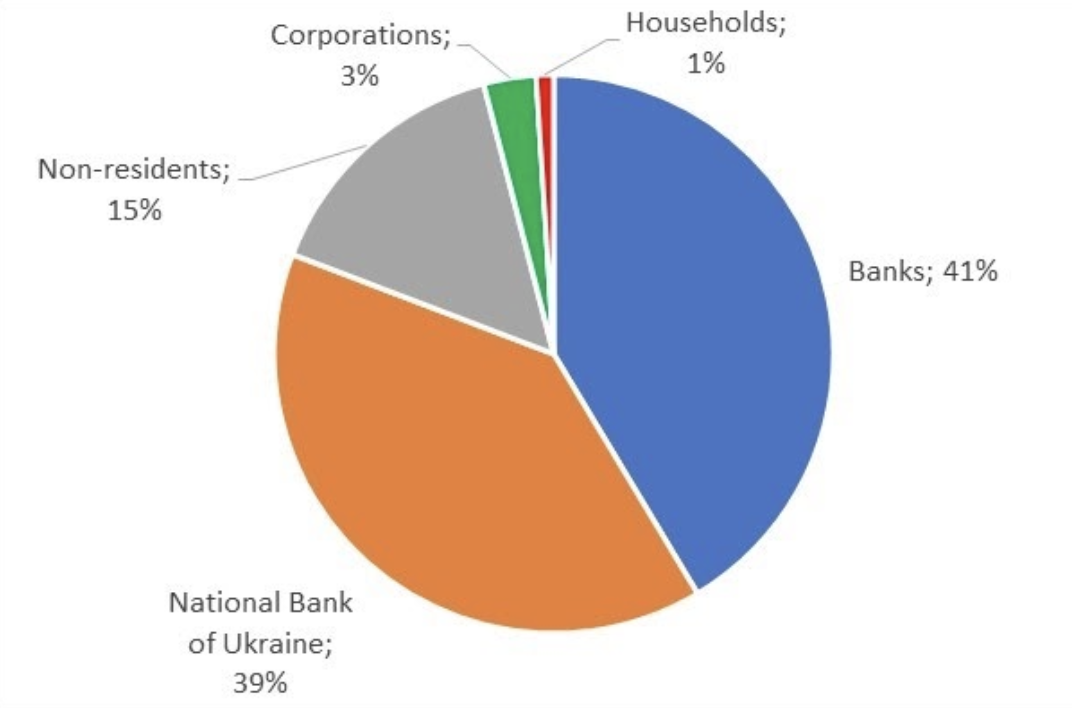

Fourth, much of government debt is held by Ukrainian banks. According to the National Bank of Ukraine, banks hold 41 percent of government bonds (the majority of this stock of bonds is held by state-owned banks, so defaulting on them would not win anything since the banks will require recapitalization from the budget). The European sovereign debt crisis paints a bleak outlook for this situation because a government default undermines the financial system and, consequently, deepens the crisis. In fact, it can create a diabolic loop: a default wipes out bank capital thus creating a banking crisis which negatively affects the economy; as the economy collapses, tax revenues decline and make defaults and budget cuts more likely; in turn, this makes the financial system even more vulnerable and the loop goes on. The 2014-2015 crisis in Ukraine could provide an approximation of what will happen after a default: a fierce run on the banks and the hryvnia and almost inevitably high inflation.

Figure 3. Composition of bond holder by owner type.

Source: the National Bank of Ukraine

In summary, the cost of default now is huge. Is there a better alternative? Yes, a program with the International Monetary Fund! It will not only provide a lifeline for the government but will also open access to other funding sources. As a result, the country can weather this storm with much smaller losses.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations