This study examines life satisfaction of students at Kyiv universities, drawing upon a unique survey conducted by the authors in November 2023. Our analysis shows that students’ contentment with life in war times is influenced by their satisfaction with studies and perceived isolation levels. Russian full-scale invasion has led to a transition towards online modes of education and, hence, study formats significantly define students’ current levels of life satisfaction. However, our results indicate that any adverse effects stemming from exposure to the realities of war can be mitigated if universities offer on-campus psychological support services. Students who report any recent improvements in their lives, even if these improvements are arbitrarily defined, also show higher levels of life contentment.

Life satisfaction plays a central role in shaping individuals’ perceptions of their roles within their workplace, community, and society. Higher satisfaction levels are associated with increased productivity, greater political engagement, and elevated motivation in various aspects of life. Ukraine is known for having relatively low levels of subjective well-being compared to European Union member states or former post-communist countries. Contributing factors often cited by studies include poverty and income inequalities. The war with Russia has created additional challenges, impacting the overall subjective well-being of Ukrainians.

War is linked with the upheaval of daily routines, displacement, disruption of social networks, and exposure to death, giving rise to a broad array of repercussions. Individuals directly exposed to the realities of war typically manifest higher levels of anxiety and stress that exert a negative impact on their overall contentment with life. Similarly, displacement creates a profound sense of loss, insecurity, and the challenges of adapting to new environments. The disruption of social networks, including family and community ties, further compounds the emotional toll, diminishing the support structures crucial for maintaining life satisfaction.

This study limits its focus to examining the subjective wellbeing of the young population in Ukraine. More specifically, the analysis centers on exploring life satisfaction among the student population of Kyiv universities. Our primary goal is to identify the key factors influencing their current contentment with life, including those directly associated with the realities of war. Our exploration is based on data derived from an online survey of students enrolled in universities of Kyiv, which was conducted and administered by the authors in November 2023. The sampling strategy relied on voluntary participation of respondents. Owing to this data collection method, we recognize the possibility of a selection bias in our sample, given that the respondents may be more self-aware of their life satisfaction than non-respondents.

Overall, 184 students provided responses in this survey. They were aged between 18 to 25, with a mean age of 18.6 years, 70.3 percent of respondents were female, and 29.7 percent were male. Additionally, half of them were students of the Kyiv School of Economics, reflecting the author’s affiliation with this university and facilitated access to the study population.

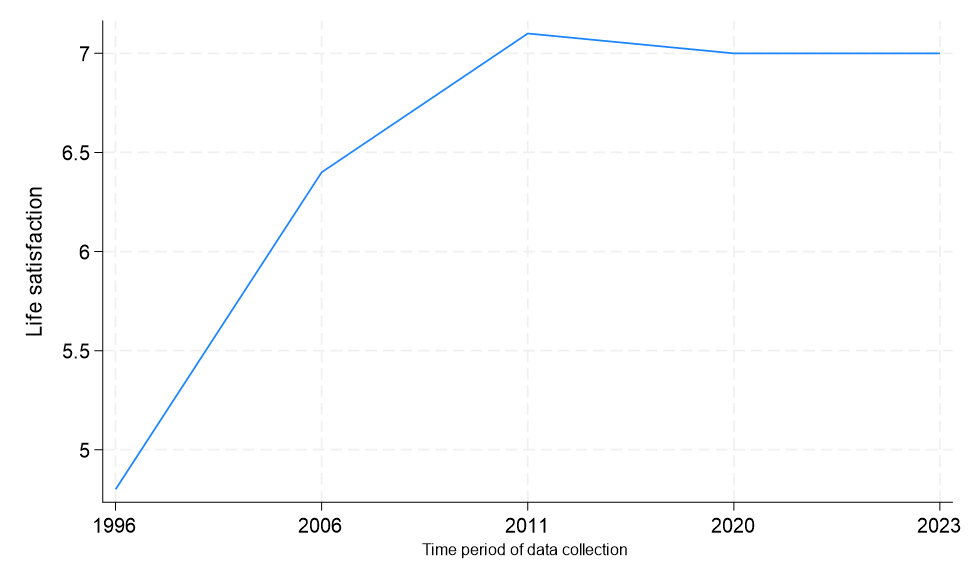

We measured life satisfaction by asking participants to evaluate their contentment with life on the 1 to 10 scale with higher values indicating increased satisfaction. The average life satisfaction of young individuals in our sample was nearly 7. Looking at the data from the World Values Survey for respondents of the same age (18-25), we can say that contentment with life has remained relatively stable among young people over the last decade (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The dynamics of life satisfaction among young individuals (18 – 25) in Ukraine

Note: The data for 1996, 2006, 2011, and 2020 come from the World Values Survey collected in the respective years. The life satisfaction scores were calculated as an average value of responses provided by individuals aged 18 – 25 to the WVS question asking to specify the extent (by using the scale from 1 to 10) to which they feel satisfied with their life.

Prior to the wave of 2011, there was a discernible upward trend in life satisfaction of the youth that stabilized thereafter. This stabilization may indicate a plato after which we would have seen a decline in life satisfaction in line with the literature that predicts an inverse-U shape of life satisfaction dynamics. However, it may also be that adverse events, such as Russia’s first invasion in 2014 and the pandemics prevented further increase in life satisfaction during the last decade.

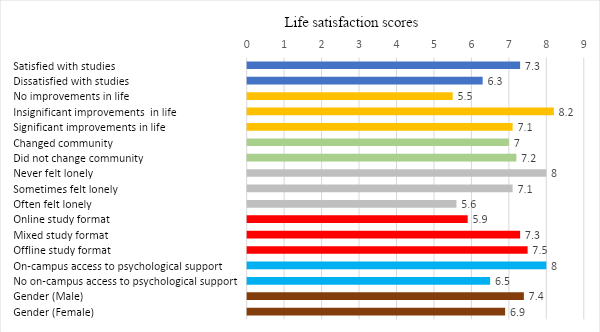

To understand the factors that impact life satisfaction of young people during Russia’s full-scale invasion, we compare the average values of contentment with life among different student groups in 2023. In selecting the key criteria for creating groups, we rely on the conventional assumption that life satisfaction of young individuals is defined by a distinct set of factors encompassing their contentment with studies, life changes, and social networks. The primary criteria considered for the analysis include the following factors: students’ satisfaction with their studies (1 = Satisfied with studies, 0 = Dissatisfied with studies), life improvements in the last 6 months (categorized as no improvements, insignificant improvements and significant improvements), relocation to another community after February 2022 (1 = relocated, 0 = stayed in the same community), the frequency of feeling lonely (categorized as never, sometimes, or often), the current study format (online, mixed, or offline), availability of on-campus psychological support at the university (1 = Yes, 0 = No), and students’ gender. Figure 2 illustrates the outcomes of this analysis. Table 1 summarizes t-test results assessing the significance of the differences in life satisfaction means for the selected groups of students.

Figure 2. A comparison of average life satisfaction levels by predictor

Note: Each color in the graph corresponds to the mean values of life satisfaction calculated for groups formed based on a specific factor. For example, the blue bars show that students who reported being satisfied with their studies have an average life satisfaction level of 7.3, while those who feel dissatisfied with their studies have an average life satisfaction level of 6.3. All the factors except for community change and gender are significant at 5% level (see Table 1 below). The differences in life satisfaction between individuals who changed their community and those who did not, as well as between male and female respondents, appear to be statistically insignificant.

Overall, our data suggests that students tend to show higher levels of life satisfaction if they feel more satisfied with their studies (7.3 vs 6.3). Students indicating recent improvements in their lives are more inclined to attribute higher scores to their contentment with life (8.2 and 7.1 as opposed to 5.5). These results support the findings that positive or negative life changes strongly predict the subjective well-being of young individuals. However, we must remember that the question regarding improvements lacked specificity on what qualifies as such, raising concerns about an arbitrary understanding that may encompass various war-related impacts.

Displacement appears to have no effect on students’ life satisfaction. Being uprooted from their usual environment and experiencing a change in living conditions and communities does not significantly impact students’ contentment with life (7.0 vs. 7.2). These findings align with previous studies showing that young people are often more flexible in adapting to new environments than adults. The ability of young individuals to navigate change effectively may contribute to their capacity to maintain contentment with life even in the face of displacement during times of war.

Nevertheless, our data suggest that any circumstances can negatively impact life satisfaction of young individuals when accompanied by feelings of isolation. Specifically, students who frequently experience loneliness report life satisfaction scores that are 2.4 points lower than those who never felt alone. These findings are in line with the existing evidence that isolation negatively impacts life satisfaction of young people.

The study format serves as an additional mechanism through which social isolation and connection to a social environment may be disrupted. Our results suggest that studying online is associated with lower contentment with life compared to studying offline, presumably due to the potential challenges related to reduced social interaction, increased feelings of isolation, and the absence of in-person engagement with peers and instructors. Online students exhibit life satisfaction scores approximately 1.6 points lower than their offline counterparts and 1.4 points lower than students that study in the mixed mode. The virtual nature of online learning may contribute to the sense of disconnection and hinder social and collaborative aspects that are often integral to traditional offline educational experiences.

Universities may influence their students’ life satisfaction by providing psychological support. Our results indicate that provision of on-campus mental health support services has the potential to augment life satisfaction levels among students by 1.5 points, presumably by promoting coping mechanisms and fostering a supportive environment conducive to high levels of contentment with life.

Finally, male students do not exhibit a significantly different level of life satisfaction compared to their female counterparts (7.4 vs 6.9) even in the face of conscription of male individuals after the completion of their studies. This observed equality in life satisfaction of young people in Ukraine can be attributed to gender egalitarian societal expectations and experiences that contribute to similar perceptions of well-being by females and males in the country.

In summary, our analysis suggests that life satisfaction of young individuals is influenced by the war in Ukraine in a very distinct manner. In particular, students demonstrate an increased sensitivity to social isolation, experienced either directly or indirectly through a transition to online forms of study. Perceived positive changes in personal life or environmental conditions significantly contribute to elevating their overall subjective well-being. The university may further amplify these levels by offering on-campus psychological counseling services. Note that our analysis was based on a sample of students from Kyiv and hence may be characterized by limited generalizability of findings. Investigating life satisfaction in regions close to active combat zones, such as Zaporizhia, Kherson, Donetsk, and Kharkiv, could yield significantly different results.

Nonetheless, even if focused on Kyiv, our analysis provides important policy implications. In particular, it is important to address the issue of isolation, which is prevalent during times of war, primarily stemming from the displacement of individuals and the disruption of familial and communal connections. Creating safe communal spaces, youth engagement programs, and educational initiatives to promote on-campus after-class engagement of students can contribute to combating social isolation and enhance youth’s satisfaction with life.

Provision of psychological support services plays a crucial role in nurturing resilience among young individuals. Hence, the government should strongly advise on the availability of on-campus mental health support services in educational institutions across Ukraine. Furthermore, universities ought to actively encourage students to utilize these services, potentially implementing compulsory sessions for all students to identify those who are particularly vulnerable and provide ongoing psychological support to them.

The subjective well-being of students will be improved if at least some studies are implemented in the traditional (offline) format. Respective policies include building shelters at the place of study to make face-to-face interaction possible even during the missile attacks. Such policies have the potential to support students during war, mitigating its repercussions not only on a personal level but also in terms of their potential to form the pool of knowledge and skills necessary for re-building Ukraine in the post-war period.

Table 1: The t-test results for differences in mean values of life satisfaction by student groups

| t-test for difference in means | |||

| Mean values | Diff | p-value | |

| Satisfaction with studies

(1 = Yes) |

7.3 | 1.0*** | 0.007 |

| (0 = No) | 6.3 | ||

| Perceived improvements in life in the last 6 months | |||

| No improvements | 5.5 | Reference | |

| Insignificant improvements | 8.2 | 2.7*** | 0.000 |

| Significant improvements | 7.1 | 1.6*** | 0.001 |

| Community change

(1= Yes) (0 = No) |

7.0

7.2 |

– 0.2 | 0.842 |

| Feels alone | |||

| Never | 8.0 | Reference | |

| Sometimes | 7.1 | – 0.9*** | 0.001 |

| Often | 5.6 | – 2.4*** | 0.000 |

| Study format | |||

| Online | 5.9 | Reference | |

| Mixed | 7.3 | 1.4*** | 0.000 |

| Offline | 7.5 | 1.6*** | 0.000 |

| On-campus access to psychological support

(1 = Yes) |

8.0 | 1.5*** | 0.003 |

| (0 = No) | 6.5 | ||

| Gender

(1 = Male) |

7.4 | 0.5 | 0.122 |

| (0 = Female) | 6.9 | ||

Note: *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations