This is an overview by the analytical platform Vox Ukraine and Tech Force inUA, an association of private arms and military equipment manufacturers. It aims to show how Russia is converting its war experience in Ukraine into arms export contracts and what our country can do about it.

The analysis provides a detailed review of the following questions: how the export of Russia’s military-industrial complex has changed since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine; why, in the fourth year of aggression, Russia continues to showcase its military achievements at international exhibitions actively; how the aggressor country profits from its war experience; and how Ukraine can gain advantages from its expertise in technological warfare and resistance against the aggressor.

For decades, the Russian Federation has positioned itself as a leader in developing the military-industrial complex and actively invested in innovations and modernization of its defense products. Within this strategy, Russia established international connections by exporting its military equipment to various countries, which allowed it to strengthen its position in the global arms market and raise geopolitical stakes. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has continued to actively demonstrate its military achievements at international exhibitions, where representatives of the aggressor state openly state that their weapons are tested in real combat conditions. This allows the country to enhance its reputation among potential partners and strengthen economic and military ties with states that support it despite international sanctions.

General overview

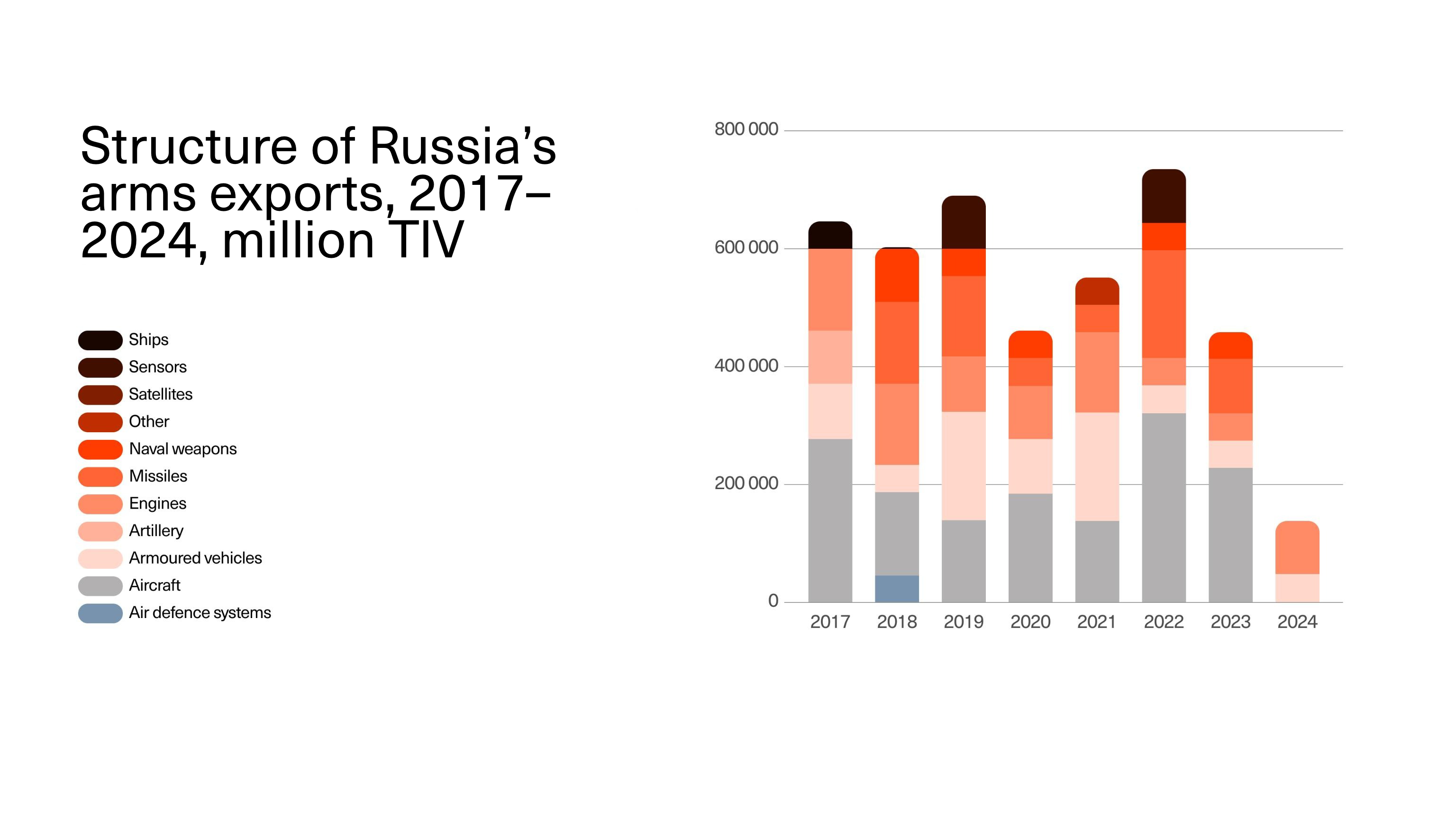

The core of Russia’s arms exports consists of aircraft, tanks, infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs), engines, and missile weapons (Fig. 1). At the same time, the available data does not show the volume of UAV sales. There may be several reasons for this: a) a ban on exporting such products from Russia; b) hidden supply contracts; c) concealment of UAV exports under the guise of other products.

Source: SIPRI

Russia is actively promoting the idea of the power of its military-industrial complex, trying to convince both domestic and international audiences of its ability not only to finance the needs of its army for the war in Ukraine but also to remain an important player in the global arms market. For example, at the end of 2024, the Federal Service for Military-Technical Cooperation stated that the portfolio of Russian arms export orders has remained at $50-55 billion for several years. In January 2025, Rosoboronexport CEO Alexander Mikheev announced that contracts worth $4.5 billion had been signed with 15 “friendly countries” at the beginning of the year alone. According to Mikheev, about 50% of the orders Rosoboronexport is currently fulfilling are from North Africa and the Middle East.

According to a Kyiv Independent investigation based on leaked Ruselectronics documents, Rosoboronexport continued to work on fulfilling contracts signed in previous years after the start of the full-scale invasion and received new requests for arms exports.

For example, Saudi Arabia, which ordered 39 Pantsir-S1 systems, missiles, and command centers from Russia in 2021 with the contract to be completed by 2026, received the first systems at the end of 2023. Armenia inquired about the possible supply of a command center for Ranzhir-M1 air defense systems, and Venezuela was interested in Pishchal-Pro and Kupol systems. These are systems that destroy unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Currently, there is no publicly available evidence that such deliveries have taken place. Such information suggests that Russia is monetizing its experience of the Russian-Ukrainian war, particularly in the field of countering drones.

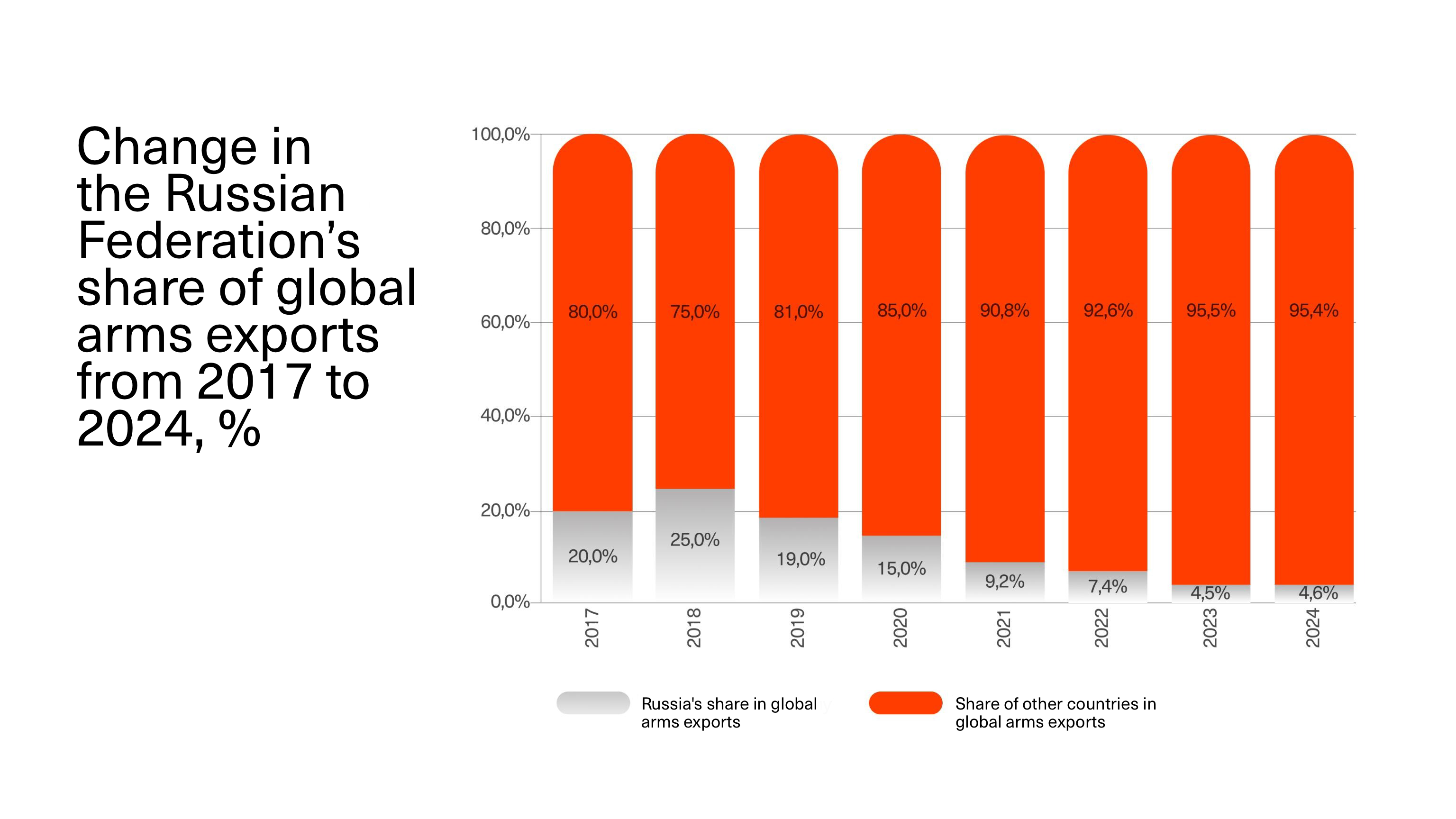

According to international organizations, Russia has weakened its position in the global market due to the need to supply weapons for the war with Ukraine. Thus, according to SIPRI, Russian arms exports have decreased by 44% since the full-scale invasion. While in 2021, Russia was ranked 3rd in the world in terms of arms sales with a 9.2% share of the global market, in 2024, it dropped to 5th place in the ranking with a 4.6% share of global arms exports, behind the United States, France, Germany, and Italy. It is noteworthy that before the aggression began in 2013, Russia was the world’s leading arms exporter, with a market share of 29%. While in 2021, Russia exported arms to 21 countries, in 2024, this number dropped to 12. In particular, deliveries to Syria, Iraq, Egypt, Ethiopia, Turkey, Nigeria, and others stopped.

Source: SIPRI

Some Russian analysts have even reported a sharp decline (14 times) in Russian arms exports compared to 2021. Thus, in 2021, revenue from arms exports amounted to $14.6 billion; in 2022, it dropped to $8 billion, and in 2023 — to $3 billion.

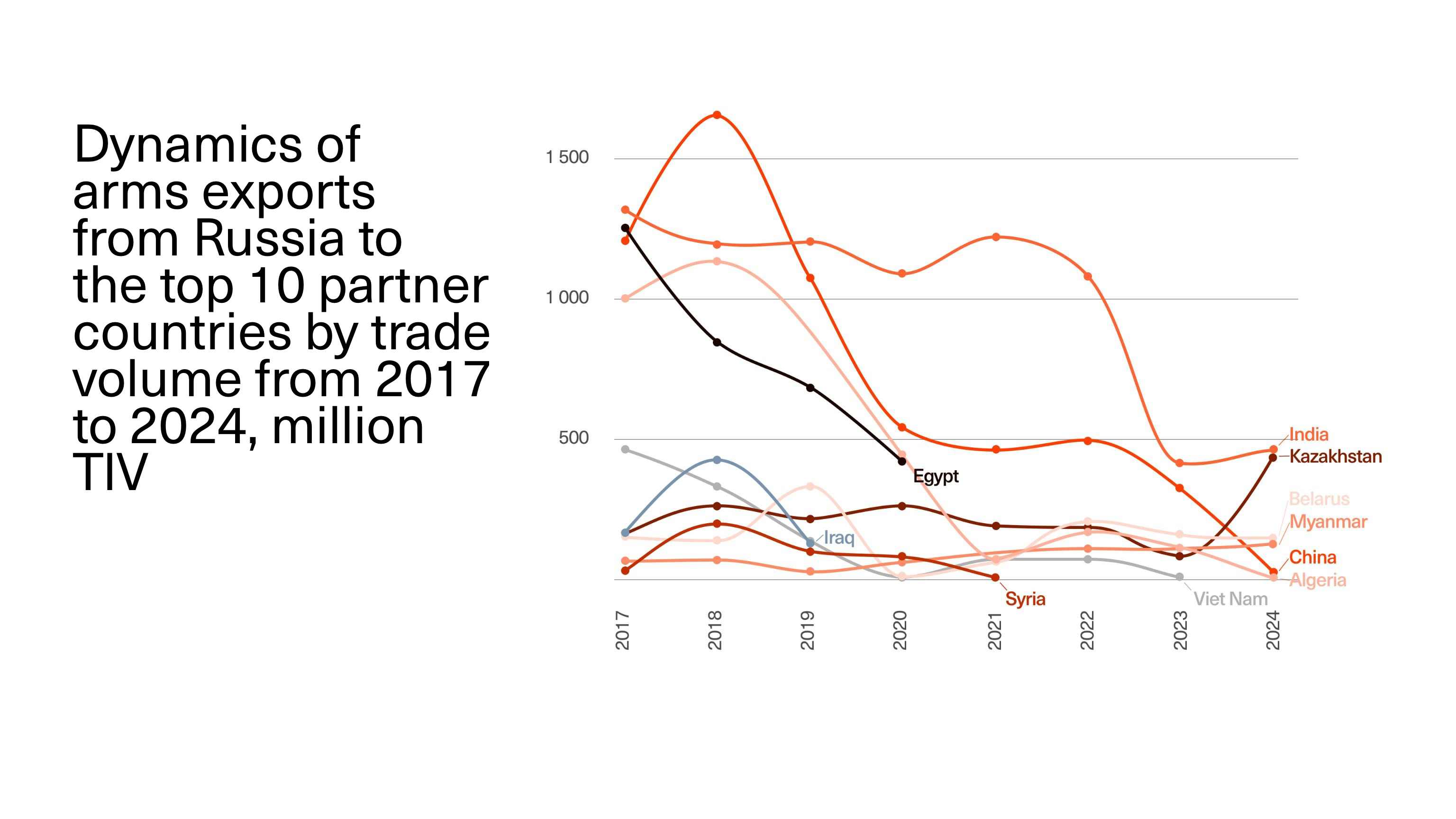

Regarding geography (Fig. 3), according to SIPRI, India is the main buyer of Russian weapons. However, every year since 2017 (except for 2021 and 2024), arms exports to India have decreased by an average of 10% (a record drop occurred in 2023 — 61% compared to the previous year). Arms exports to China (CAGR -37%) and Algeria (CAGR -44%) have dropped by almost a third in 7 years. Despite previous close cooperation, exports to Syria, Egypt, Iraq, and Vietnam stopped in 2024.

Source: SIPRI

Positive export dynamics in 2017-2024 were observed only in trade with Kazakhstan (CAGR +13%) and Myanmar (CAGR +9%), and the volume of arms sales to the Republic of Belarus remained virtually unchanged (CAGR -1%). Despite the sharp decline in arms exports to Kazakhstan in 2023 (-54% compared to 2022), the volume of arms supply contracts increased almost 4 times in 2024. Arms exports to Myanmar also increased in 2024 (+20% compared to 2023). The volume of arms exports to Belarus remained roughly constant until 2022, except for an almost complete decline in arms sales in 2020, which was apparently due to the presidential elections in Belarus. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russia, the volume of arms exports to the Republic of Belarus has been declining (by 22% in 2023 and 8% in 2023). However, it is obvious that Russia continues to arm Belarus under the Treaty on Security Assurances within the Union State, which is not always accompanied by relevant contracts that SIPRI takes into account in its statistics.

Development in the UAV segment

According to the Russian government’s decree of March 10, 2022, the export of aircraft, drones, and satellites from Russia is temporarily banned until the end of 2025. These restrictions are explained by the priority use of drones in the so-called “area of the special military operation”. In the summer of 2023, Rusdronoport emphasized that it was not exporting drones, as they were banned due to the urgent need for them at the front.

However, the Russian government is actively promoting the idea of setting up a new economic sector related to the creation and use of drones. In particular, in June 2023, the Strategy for the Development of Unmanned Aviation of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2030 and prospectively to 2035 was signed. The strategy includes five key areas: stimulating demand for domestic UAVs, their development and mass production, infrastructure development (airfields, heliports, drone ports), training and research in this area. The Strategy emphasizes stimulating the development of civilian UAS (unmanned aerial systems), but it is likely that a significant share of the targets will be related to military needs.

Table 1. Targets for the development of unmanned aerial vehicles in Russia according to the Strategy established by the government in 2023

| Indicator | Russian UAS market volume (demand), units | Number of UASs produced in Russia, units | Number of specialists in the field of research, development, production, and operation of UASs | |||

| Scenario | basic | progressive | basic | progressive | basic | progressive |

| Plan for

2023-2026 |

372 700 | 389 700 | 52 100 | 55 400 | 330 000 | 450 000 |

| Plan for

2027-2030 |

684 500 | 718 800 | 105 500 | 116 800 | 1 000 000 | 1 100 000

|

| Plan for

2031-2035 |

989 500 | 1 039 000 | 177 700 | 199 100 | 1 500 000

|

1 600 000

|

* The basic scenario assumes stable development of the UAS market with an average growth of 14% per year, with peak production in 2025-2027. The progressive scenario predicts 25% growth, an increase in the share of domestic UAS in the market, and possible exports to friendly countries

Given that the Russian government has developed a Strategy for the development of the industry, we can expect a significant increase in revenues of companies engaged in the production of UAVs. According to reports from Russian drone manufacturers submitted to the federal authorities of the Russian Federation, they receive excessive profits. They can also purchase components for drones even despite the sanctions (hence, sanctions against Russia need to be strengthened). Although most of them declare that the drones they produce are for civilian use, there is still information about gratitude from the government for the supply of drones for military purposes.

As of 2023, there were 570 aircraft manufacturing companies in Russia, and 200 of them were registered after the start of the full-scale invasion. A similar trend is observed in the production of FPV drones — most of the companies were registered in 2023.

The National Technology Initiative Fund plans to finance 400 more drone development startups in Russia by 2030, with 30 billion rubles (almost $335 million) allocated for this purpose.

As for the companies’ earnings, the market price of Russian FPV drones is relatively low due to cheap labor and mass production. The average price is $2966, which increases the demand for them among foreign partners.

Table 2. Prices for Russian-made FPV drones

| FPV drones costing up to $700 | FPV drones costing up to $2000 | FPV drones costing over $2000 |

| Grach – $310.8

Stuzha, Vyuga – $330 – $440 Piranha – $340 – $503 Boets 40 – $430 Hava – S530-630 Upyr-88 – $550 Bekas – $550 VT-40 – S550 ZvyoZdochka – $650 |

Muravey – $880

Geoscan Pioner FPV – S991 Rusak-S-S1000 Dobrynya – $1084 – S1777 Privet-82 – S1200 ZvyoZdochka – $1300 Ovod-10 – $1500 Sarmat – S1546 |

MiS-35 – $4 345-6 345

Sibiryachok – $10 962-27 405 Izdelive 1-390 – $13 945 |

Exhibitions and export plans

After the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia continues to hold its own arms exhibitions and attend them in other countries. This indicates that Russia is expanding its military cooperation with different regions of the world despite international sanctions. Russian companies demonstrate the latest technologies in the defense sector, including UAVs, and are considering the possibility of establishing joint ventures to produce weapons and equipment in “friendly countries”.

Table 3. Examples of russia’s participation in exhibitions

| Exhibition | Country | Year | Weapons presented |

| IDEX | Abu Dhabi, UAE | 2023 | Ka-62 and Ka-226T helicopters, Iskander-E air defense systems, 9K515 MLRS (Tornado-S), Khrizantema

-S and Kornet-E, Orion-E, Orlan-10E and Orlan-30 UAVs |

| «Army» | Russia | 2022

2023 2024 |

Ka-52E, Mi-28NME, Mi-17 helicopters, Orion-E, Orlan-10E, Orlan-30, Kub-E UAVs |

| Airshow China 2024 | Zhuhai, China | 2024 | Orlan-10E, Orlan-30, Skat, Kub-E UAVs |

| World Defense Show 2024 | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | 2024 | Armored vehicle Typhoon, Orlan-10, Orlan-30, TOS-1A, Kornet-EM UAVs, small arms |

| Africa Aerospace and Defense Expo 2024 | Pretoria, South Africa | 2024 | Orion-E, Orlan-10E, Orlan-30, Skat, Kub-E UAVs |

| IDEX | Abu Dhabi, UAE | 2025 | Supercam S350 UAV, Т-90МS tank, Forpost-RE, Pantsir-SMD-E, Lancet-E UAVs |

| Aero India-2025 | Bengaluru, India | 2025 | Su-57E, Lancet-E, S-400 Triumph, Karakurt and Goliath UAVs |

Note: The table does not contain an exhaustive list but some examples of the presented weapons.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia has participated in a number of international arms exhibitions, including the largest IDEX in Abu Dhabi, Airshow China 2024 in Zhuhai, World Defense Show 2024 in Riyadh, Africa Aerospace and Defense Expo 2024 in Pretoria, and Aero India 2025 in India. The Middle East, Asia, and Africa were expected to become key areas for Russia.

During these exhibitions, Russia tried to promote joint arms production, adapting its offer to the needs of the regions. For example, in the Persian Gulf, they actively promoted drones for monitoring infrastructure and combating terrorist threats (for this purpose, they offered Supercam S350, Orlan-10E, and Orlan-30 UAVs), while in India, they focused on joint projects in the field of aviation and armored vehicles.

At the same time, Russia organized its exhibitions. The most significant is the annual Army Forum, which is both a propaganda tool and a tool for promoting Russian weapons abroad. In addition to Russia, six countries presented their exhibits in 2024: Belarus, Vietnam, India, Iran, Pakistan, and China. Although the number of participants is limited, these countries have large markets, and Russia primarily focuses on them.

Russia is trying to use the opportunity to attend such events not only to demonstrate its military strength. The exhibitions mainly feature export weapons or export modifications of conventional weapons. During the presentation of the samples, Russia refers to its experience of using them in combat during the Russian-Ukrainian war. In other words, Russia is trying to sell the experience of a full-scale invasion.

Russia is expanding the amount of equipment it displays at exhibitions, changing its emphasis. For example, Russia is increasing the number and type of UAVs on display:

- At IDEX 2021, Russia presented the Orlan-10E UAV.

- At IDEX 2023, the Orion-E, Orlan-10E, and Orlan-30 UAVs.

- At IDEX 2025 – Supercam S350, Forpost-RE, Karakurt, Goliath, Quasimatch, Kub-10E, Lancet-E UAVs.

In addition to expanding the range of UAVs, Russia is also demonstrating equipment that can counter various types of drones or unmanned aerial vehicles. For example, at IDEX 2025, the demonstration of the T-90MS emphasizes its anti-drone defense. An updated version of the Pantsir-SMD-E was also presented. Although traditional types of weapons are not disappearing from the exhibitions, there is a noticeable emphasis on the current requirements of the battlefield, where unmanned and robotic systems play a significant role.

At international exhibitions, Russia mainly demonstrates weapons that it claims to be able to produce in excess or potentially capable of producing in excess. The main task of its defense enterprises is to meet the needs of the front line. For this reason, Russia seeks not only to export its products but also to create joint ventures with partner countries to reduce the burden on its industry and expand production capabilities, particularly to purchase technologies to circumvent sanctions. At exhibitions, Rosoboronexport stated that the main vector of partnership is shifting towards joint development and the production of weapons.

Plans to create joint ventures

Russia has planned to establish joint ventures (JVs) since the beginning of its invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and is currently actively engaged in JVs to strengthen its manufacturing capabilities, particularly in the field of drones. These projects are aimed at meeting domestic arms needs, but their scope may also include supplies to foreign markets.

Iran is one of Russia’s key partners in joint production of UAVs. In cooperation with Iran, Russia has established a drone production facility in the Alabuga special economic zone in Tatarstan. This plant produces barrage munitions similar to Iran’s Shahed, as well as Albatross reconnaissance drones. The plant has been operating since July 2023 and, according to initial plans, should produce 6,000 drones per year with further expansion plans.

Another partner in the joint venture is likely to be China. According to information published by Reuters, Russia has launched a covert program in China to develop and produce Garpiya-3 (G3) long-range attack drones for use in the war against Ukraine. Local specialists have been working on the development. The Chinese Foreign Ministry says it is not aware of such a project.

According to Bloomberg, Russia and China are jointly developing the Sunflower 200, which is supposed to be an analog of the Shahed 136. Also, Chinese companies Fimi, AEE, and ZeroZero, which are involved in civilian drones, wanted to either organize production in Russia or create a joint venture with Russian developers. Defense Express claims that many Russian unmanned systems rely heavily on components purchased from the People’s Republic of China, some of which are even fully developed by local companies but disguised as Russian products.

In early March 2025, it was reported that Russia proposed to establish a drone manufacturing facility in Belarus, which would be capable of producing up to 100,000 drones per year.

Russia plans to further expand joint ventures and create new ones, expanding the geography of production. According to representatives of the Russian Federation, a significant number of countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia are interested in joint production of Russian weapons.

In February 2025, the head of Rosoboronexport said that Russia is implementing about 20 projects in partnership with 10 countries in the North Africa and Middle East region to jointly develop and produce UAVs, precision munitions, small arms, and armored vehicles.

In February 2025, the Russian group of companies Kronstadt announced the possibility of localizing production and establishing joint ventures in India. According to the organization, India is interested in Orion UAVs. Russia is also interested in joint production of a 5th-generation fighter jet in India. At the Egyptian International Airshow, which took place in September 2024, the possibility of joint development of an aircraft based on the Su-57 fighter was discussed.

The Russian company Transport of the Future also plans to enter the Indian market in partnership with the local Sasaa Electronics Private Limited. The parties will establish a joint venture to assemble drones for the local market, expecting to take up to 25% by 2030.

In September 2024, Russia considered localizing the production of civilian drones and components in Uzbekistan. It is not yet known whether there are plans to produce UAVs for military use. Russian companies Vega and ZALA Aero Group have representative offices in Kyrgyzstan.

In addition to the aircraft, Russia was considering localizing the production of the Pantsir-S1 in Saudi Arabia, which would allow Russia to earn even more from arms sales than the €2 billion contract under which it sold air defense systems to the country. However, the project has not yet begun.

Japanese TV channel NHK World, citing sources, claims that North Korea will develop drones in cooperation with Russia. Their production should begin in 2025 as a payment for the involvement of the Korean military in the Russian-Ukrainian war.

Thus, Russia is trying to expand its capabilities in joint arms production. In addition to traditional weapons, Russia places considerable emphasis on the joint production of various types of drones. Currently, according to Russian representatives, they are planning or counting on joint ventures with a wider range of countries. This can be either a joint venture or localization of production in Russia or another country. How successful their actions in this direction will be remains to be seen.

The regions Russia uses to implement its plans to establish joint ventures or localize production are Africa, Asia, and the CIS countries.

Geopolitical consolidation of position

Russia uses arms exports not only as a source of revenue but also as a tool for establishing and strengthening geopolitical ties. Exports of modern weapons systems allow Moscow to increase its influence in strategically important regions, such as the Middle East and Africa, and build long-term political and military alliances.

Moreover, Russia is actively seeking partners for joint projects and technological cooperation in countries without international sanctions, particularly in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

In addition to arms exports and plans for joint ventures, Russia is deploying paramilitary forces, such as the African Corps, to strengthen its influence on the continent. This structure was created as a successor to the Wagner Group and operates under tighter control of the Russian state. The African Corps cooperates with the governments of countries such as Libya, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and the Central African Republic, providing military equipment and support in the fight against “terrorism”.

However, the war against Ukraine has significantly undermined the aggressor’s ability to maintain its position in the arms market, although it is still widely represented there. The main problems of the Russian Federation at the moment are:

- Western sanctions make accessing high-tech components for weapons production, such as aircraft engines and electronics, difficult.

- Reorientation of production. Much of Russia’s defense industry is focused on recovering from losses on the battlefield, leaving fewer resources for exports.

- Decreased confidence of importers. Some traditional partners (e.g., Egypt, which worked closely with Moscow after the 2013 coup but canceled a lucrative contract to purchase Su-35 fighter jets in 2022) are refusing to sign deals with Russia for fear of sanctions or technical delays.

- The Russian Federation cannot compete with other suppliers — the United States, China, Turkey, and other countries are actively occupying the niches that are being vacated by Russia’s weakening.

- For Ukraine, which will seek to expand its defense industry and enter global markets after the war, Russia’s current weakening position creates a unique window of opportunity.

How Ukraine can benefit from the experience of war and countering the enemy

The Ukrainian defense industry is already prepared to offer innovative solutions that have been tested in combat conditions, and there is a demand for this expertise. According to TFUA, most NATO countries have already approached Ukrainian manufacturers for partnerships or weapons supplies.

For example, the success of Ukrainian naval drones is of interest. Russia is already trying to monetize its experience in countering drones, and Ukraine can compete with it in this area.

It is important that as many countries as possible seek Ukraine’s experience rather than Russia’s.

To make this possible, Ukraine should

- enter international markets with its technological warfare expertise and innovations,

- continue to advocate and insist on the need to strengthen sanctions against Russia, making it impossible for the aggressor to attend international events and reduce opportunities for joint ventures and the supply of components for the Russian defense industry.

With open arms exports, Ukraine could actively present advanced models to potential partners at international exhibitions and offer technological cooperation, including through joint production.

Ukrainian producers are ready and waiting for the opening of exports, which is important today for enhancing collective security and integration into global supply markets. Such integration increases the competitiveness of Ukrainian producers in the world market and strengthens their position in the global economy. Moreover, this would not only contribute to a technological break from the enemy but could also serve as a counterweight to Russia’s intentions to regain its lost share of the global arms market.

Authors:

- Viktoriia Ahapova – Senior Analyst, Reform Index Deputy Head;

- Viktor Sholudko – VoxCheck Analyst;

- Kateryna Ionova – VoxCheck Analyst;

- Mariia Balytska – Vox Ukraine Analyst;

- Dariia Kolodiazhna – Vox Ukraine Dana Analyst;

- Alina Tropynina – VoxCheck Managing Editor;

- Kateryna Mykhalko – Director-General of Tech Force in UA.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua/

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations