A recent publication on Vox Ukraine examined how war influences the dynamics of social trust. Based on data analysis, the author concludes that war leads to a decline in trust between people.

The article makes an important contribution to studying social trust during wartime, but it also has two methodological limitations. First, its conclusions are drawn from cross-sectional data: changes in trust are inferred from correlations between respondents’ answers at a single point in time. In other words, the dynamics of social trust were evaluated in a static context rather than through comparisons across different time periods. Second, the “war” variable was constructed as a latent factor, with weak correlations among conceptually distinct indicators—raising questions about the quality of the measurement tool.

In this column, we seek to contribute to the discussion on how war affects trust. Specifically, we will analyze changes in social trust over time and analytically distinguish between the impact of “war as an event” and the traumatic experiences people endure during wartime.

War as an Event

In this case, we treat war as a time period and assume that everything occurring during it happens under its influence. To capture its impact on social trust, we, therefore, compare trust levels at different points in time—before and during the war. On the one hand, this approach reduces the risk of missing any manifestation of the war’s effects. On the other hand, it carries the risk of “capturing too much”: fluctuations in social trust that are actually caused by events unrelated to the war[1].

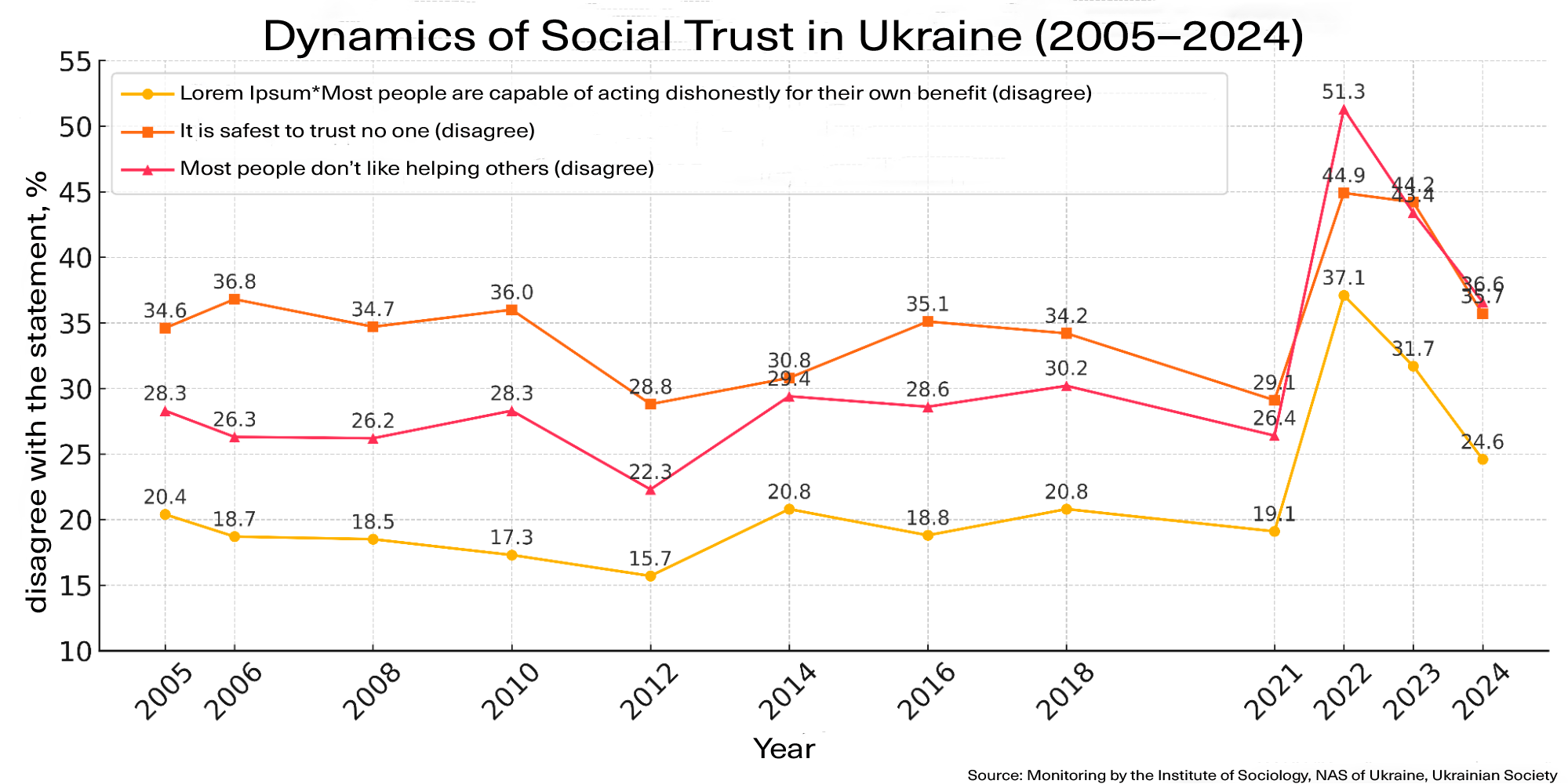

The Institute of Sociology conducts an annual survey of the adult population in Ukraine (Ukrainian Society, 2024), which allows us to track changes in social indicators over time. Some of the questions directly relate to social trust: “Most people are capable of acting dishonestly for their own benefit,” “It is safest to trust no one,” and “Most people, deep down, do not like to go out of their way to help others.” Respondents evaluated these statements on the following scale: 1 = agree, 2 = disagree, 3 = don’t know. Figure 1 shows the share of those who disagreed with the statements. From 2005 to 2021 (i.e., before the full-scale invasion), the level of social trust remained largely unchanged. But in 2022, we observe a sharp increase in trust—almost doubling across all three indicators. In 2023–2024, trust declined slightly but still remains higher than it was before the full-scale invasion.

Figure 1. Dynamics of Social Trust, 2005–2024

According to a survey conducted by Info Sapiens in August 2022, an increase in trust toward various social groups during the war was also recorded (Info Sapiens, 2022). Compared to 2020, Ukrainians expressed greater trust in family members, acquaintances, neighbors, and people of different nationalities and religions. Only trust in people they were meeting for the first time showed a slight decline.

In a previous publication (Moskotina, Karakai, & Hatsko, 2025), we also examined changes in social trust during the war. Using data from the LIWS panel study, we showed that with the onset of the full-scale invasion, both belief that others would try to be fair and the perception that people are generally helpful increased.

Thus, findings from three separate studies point to an increase in social trust during wartime. At the same time, data from the Institute of Sociology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine indicate that, over time, trust has begun to decline and is nearing pre-war levels. However, it remains uncertain whether this downward trend will persist.

War as a Traumatic Experience

Another approach takes into account the fact that people experience war in different ways. Some, during the full-scale invasion, never heard a single explosion, while others lost loved ones or their homes. In this view, war can be understood as a set of traumatic events that happened to people during that time. The underlying assumption is that the more someone suffered during the war, the greater the “impact” of the war on them. According to this approach, evidence of the connection between war and social trust should be sought by comparing respondents who were more or less affected. This method aims to minimize the inclusion of events unrelated to the war in the analysis, but it risks overlooking important aspects of the war that may influence social trust.

Hoch et al. (2025) demonstrate that how we measure “being affected” by war significantly influences results. The researchers examined the relationship between war and prosocial behavior, measured as a latent factor based on questions about social trust, altruism, and willingness to reward kind behavior [2]. War experience was assessed using two approaches: (1) the number of military incidents (missile strikes, drone attacks, direct combat, etc.) within a 10-kilometer radius of the respondent’s residence, and (2) respondents’ self-reported experience of one of 19 stressful war-related events. The results showed that proximity to combat was correlated with decreased prosocial behavior, whereas personal traumatic experience was associated with increased prosocial behavior.

The authors suggest that the difference in responses to the war depends on the extent to which the experience was personal for each respondent. We expand on this idea by outlining specific theoretical mechanisms that could help explain this apparent contradiction in the data, particularly in the context of social trust.

Indirect exposure to war: Deaths and destruction occurring nearby can increase anxiety. In the social sciences, trust is often associated with a willingness to take risks, as it involves making oneself vulnerable to the actions of others (Siegrist, 2021). Heightened anxiety may amplify perceived risks, thereby reducing one’s willingness to trust.

Personally experienced trauma: First, trauma can foster positive interactions with others. People who experience hardship are more likely to seek help from those around them. For example, someone who has lost their home due to the war may receive support from relatives, neighbors, or colleagues — in the form of temporary shelter, financial aid, or emotional support. A positive experience of such interaction can strengthen trust in others. Second, traumatic experiences can cultivate empathy toward others who have gone through similar difficulties. This empathy promotes greater trust by deepening one’s understanding of others’ feelings and increasing the willingness to cooperate[3].

The study by Hoch and colleagues is cross-sectional, which introduces certain methodological limitations. When people are surveyed only once, it is difficult to establish causal relationships, as we cannot account for the temporal sequence of events or for respondent characteristics that remain constant over time. Moreover, their study examines the relationship between prosocial behavior and war experience, while in this publication, we are specifically focused on social trust. Therefore, we chose to replicate part of their analysis using panel data, focusing specifically on social trust. Drawing on data from the LIWS panel survey, we examined whether traumatic experience predicts changes in social trust.

The survey was conducted by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in two waves. The first wave (January 18 – February 8, 2022) involved in-person CAPI interviews with 1,531 respondents aged 15 and older in government-controlled areas (response rate: 30.2%). The second wave (August 24 – October 6, 2022) used CATI phone interviews with 595 participants—representing 39% of the original sample and 47% of those who had agreed to follow-up contact. Due to lower accessibility in rural and frontline areas, the second wave primarily represents urban residents and respondents from western regions of Ukraine. Full details of the panel study are available at the following link. The reproducible data analysis code is available here.

To account for both the presence of traumatic experiences and their intensity, we constructed two indicators: a binary variable capturing whether the respondent experienced any traumatic event and an index reflecting the total number of events experienced.

In the second wave of the panel survey, respondents reported whether they had:

- experienced material losses (such as loss of income, employment, housing, or property);

- suffered physically (e.g., deterioration of health or injury) or psychologically;

- been separated from their family or experienced the loss of loved ones (e.g., the death of acquaintances or relatives);

- been forcibly displaced[4].

If at least one of these events occurred, the respondent was classified as having experienced trauma (0/1). We also constructed a traumatic experience index[5], defined as the number of such events reported by the individual, ranging from 0 to 10. Each event in the index was given equal weight: for example, being forcibly displaced contributed as many points to the victimization score as the loss of a loved one.

We examined two indicators of trust: how honest respondents believe others to be and how willing they think others are to help. Both variables were measured on a 10-point scale (0 = expectation of dishonesty/selfishness; 10 = expectation of honesty/mutual aid from fellow citizens).

To determine whether traumatic war experience affects changes in social trust, we applied a linear regression model with random effects. Since we used two indicators to measure traumatic experience and two indicators to measure social trust, we constructed four regression models—one for each combination. These models estimate levels of social trust based on three variables: the survey wave, the traumatic experience, and the interaction between the survey wave and the traumatic experience. We additionally control for respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics, including age, gender, education level, region of residence, type of settlement prior to the invasion, and household income. These variables are included as potential confounders, as they may affect both the likelihood of experiencing the consequences of war and the level of interpersonal trust.

Our primary focus is the interaction coefficient between the survey wave (before or after the invasion) and traumatic experience. This coefficient indicates whether the change in trust over time differs between those who experienced war-related losses and those who were not directly affected.

Table 1 presents the results of the analysis. Neither the presence of traumatic experience nor the number of traumatic events had a statistically significant effect on changes in social trust after the invasion[6]. None of the interaction coefficients with the survey wave were statistically significant. Thus, we found no evidence that individual traumatic experiences caused by the war lead to a decline in social trust.

Table 1. Results of the Random-Effects Model

| In your opinion, do you think that most people would try to take advantage of you if they got the chance, or would they try to be fair? | In your opinion, would you say that most of the time people try to be helpful or that they are mostly looking out for themselves?? | |||

| Any Traumatic Experience | Traumatic Experience Index | Any Traumatic Experience | Traumatic Experience Index | |

| Intercept | 2.62**

(0.86) |

3.01***

(0.74) |

3.13***

(0.83) |

2.71***

(0.72) |

| Wave 2 Change | 1.50*

(0.63) |

1.49***

(0.30) |

2.04**

(0.65) |

2.38***

(0.32) |

| Presence of Traumatic Experience (in Wave 1) | 0.31

(0.50) |

-0.37

(0.49) |

||

| Wave 2 Change × Traumatic Experience | 0.35

(0.65) |

0.38

(0.67) |

||

| Traumatic Experience Index (in Wave 1) | -0.03

(0.07) |

0.02

(0.07) |

||

| Wave 2 Change × Traumatic Experience Index | 0.11

(0.08) |

0.01

(0.09) |

||

| SD (Intercept ID) | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.50 | 0.49 |

| SD (Observations) | 2.29 | 2.28 | 2.43 | 2.43 |

| Num.Obs. | 948 | 948 | 969 | 969 |

| R2 Marg. | 0.176 | 0.175 | 0.234 | 0.234 |

| R2 Cond. | 0.281 | 0.283 | 0.264 | 0.264 |

| AIC | 4462.2 | 4470.1 | 4593.3 | 4601.7 |

| BIC | 4632.1 | 4640 | 4764 | 4772.3 |

| ICC | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| RMSE | 2.15 | 2.15 | 2.38 | 2.38 |

+ p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Note: Standard errors are shown in parentheses. To avoid overloading the table, coefficients for control variables are not reported.

Conclusion

We observe a clear fact: in 2022, the level of social trust in Ukrainian society increased significantly. This finding is supported by several independent sources, including panel data that allow comparisons of the same individuals before and during the war. If we adopt a broad interpretation—where everything that occurs in wartime is treated as a consequence of war—then war appears to foster social bonds.

Research suggests that the impact of traumatic experiences on social ties depends on how individual “exposure” to war is defined. Personally experienced grief may enhance prosocial behavior, while living in dangerous conditions may undermine it.

We tested the relationship between changes in social trust and personal traumatic experiences using panel data. Our analysis did not confirm either an increase or a decrease in social trust: neither the occurrence of trauma nor the number of traumatic events accounted for changes in trust during the war. One possible explanation is that we did not consider whether respondents’ interactions with others after experiencing trauma were positive. Individuals with greater social capital—those with more social connections—may have received support from others, and such positive experiences could have strengthened their trust. In contrast, those who did not receive help may have become less trusting. We encourage other researchers to explore this potential moderating effect in future studies.

A Note on Researching the Consequences of War

War can take many forms, and depending on how we choose to measure it, we may arrive at opposing conclusions. In our view, “war” is not a productive concept for explaining social change in Ukraine—the term is too vague. Rather than studying the general impact of war, we propose focusing on specific theoretical mechanisms—such as traumatic experience → support from others → increased trust, or growth in social capital → greater support → increased trust—that drive these changes during wartime. This approach enables researchers to offer more concrete and actionable recommendations for alleviating the negative consequences of war while enhancing its potential positive effects.

[1] In this column, we will focus solely on comparing the periods before the full-scale invasion and during the invasion.

[2] (1) Social trust was measured by agreement with the statement: “I believe that people have only good intentions.” (2) Altruism was measured using responses to the following questions: “To what extent are you willing to do noble deeds without expecting anything in return?” and “Imagine the following situation: Today you unexpectedly received UAH 1,000. How much of this amount would you donate to good causes?” (Response options ranged from 0 to 1,000). (3) Willingness to reward kind behavior was measured by agreement with the statement: “When someone does me a favor, I try to return it.”

[3] On the other hand, traumatic experiences can also contribute to a decline in social trust. People who did not receive support from those around them when they needed it may begin to trust others less. Similarly, individuals who went through traumatic war experiences may become less empathetic toward those living through the war in relative safety—and, as a result, may also trust them less.

[4] These indicators are commonly used in studies examining the effects of war and encompass all major dimensions of victimization at the individual level: primary, material, and secondary (Yaylacı and Price, 2022).

[5] The index does not measure a latent variable and, therefore, does not assume internal consistency among the items. In the literature, this approach is referred to as formative (Diamantopoulos & Winklhofer, 2001): the construct is not “reflected” in the items but is instead formed by their combination. Hoch and colleagues constructed their measure of traumatic experience in a similar manner (Hoch et al., 2025).

[6] We also separately tested the effect of each specific type of traumatic experience (e.g., job loss, injury, displacement) on changes in social trust—none of them yielded statistically significant results. These additional findings are not included in the table, but interested readers can verify them using the open and reproducible code available in our data repository.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations