“Up to a million migrants will arrive in Ukraine, and for them even $10–15 counts as big money” – this is one of the most common scare stories about foreigners supposedly taking jobs from Ukrainian citizens. Vox Ukraine examines how grounded these fears really are and what Ukrainians should actually expect.

An estimated 28-34 million – this was Ukraine’s population at the start of 2023, according to the Institute of Demography. Over the past two years, the situation has certainly not improved: the zone of active hostilities has expanded, the enemy has unfortunately occupied additional Ukrainian territory, and the government has allowed men up to age 22 to leave the country. Employment has fallen from 56% in 2021 to 50% in 2024, while the share of economically inactive people has risen from 37% to 44%, and the remainder are still seeking work. It is also hardly realistic to expect that children, pensioners, or service members can be brought into the labor market on a large scale.

Labor power is the foundation of the economy – people produce goods, provide services, and keep businesses moving forward. When workers are in short supply, firms reduce output, their costs rise, and they are forced either to raise prices or operate with lower profits, resulting in lower investment in development and lower tax payments.

As in advanced European countries, mortality in Ukraine exceeds births, and the population is steadily aging. The war has intensified these long-term trends. In 2024, for example, the mortality rate was three times higher than the number of births. This is partly because women of reproductive age are postponing childbirth amid uncertainty and danger, and partly because many potential mothers have left for safer countries abroad.

Figure 1. Trends in births and deaths in Ukraine

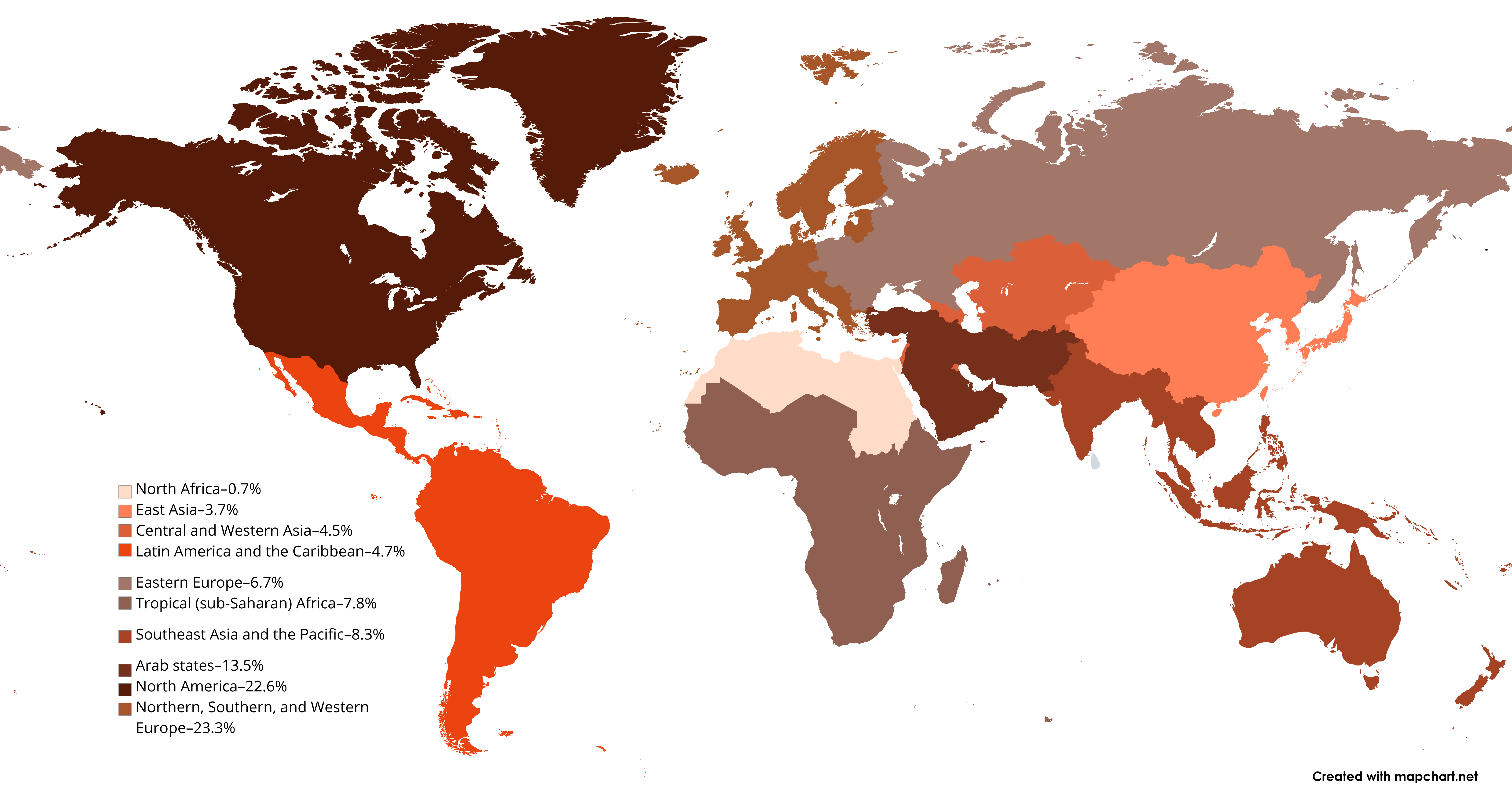

One way to address demographic crises when a country lacks sufficient domestic workers is to bring in labor migrants. They fill open positions, which in turn boosts production, increases tax revenues, and strengthens financial stability. As of 2022, globally, there were 167.7 million labor migrants, accounting for 4.7% of the total workforce. Nearly one-third of them are concentrated in high-income countries across three subregions: 23.3% in Northern, Southern, and Western Europe, 22.6% in North America and 13.5% in the Arab states.

Figure 2. Regional distribution of labor migrants worldwide as of 2022

Worldwide, in 2022, there were 167.7 million labor migrants, comprising 38.7% women and 61.3% men. The main employer of labor migrants in 2022 was the services sector, which accounted for 68.4% of all migrant workers. Another 24.3% were employed in industry and 7.4% in agriculture. The services sector is especially attractive to women, with nearly 81% of female migrants working in this sector, whereas men are more often employed in industry or agriculture.

Figure 3. Composition of labor migrants (data as of 2022)

According to estimates by the Ministry of Economy, over the next decade, Ukraine will need to bring at least 4.5 million workers into its labor market. Clearly, attracting migrants could be one way to address Ukraine’s labor shortages. And this is not a new idea – before the full-scale war, Ukraine was already receiving labor migrants who came to work, study, or reunite with family. Even now, some Ukrainian companies are trying to recruit workers from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Central Asian countries; however, their share remains low (Figure 5).

As before the war, most foreigners came for personal reasons (Figure 4), for example, to reunite with their families (91% in 2020 and 98% in the first half of 2025). Others come for service or study, and the smallest share comes for work.

Figure 4. Reasons for foreigners’ entry into Ukraine

After the full-scale invasion, there was a noticeable redistribution of foreigners’ migration flows (Figure 5). Before 2022, most entries came from countries to the east of Ukraine, but the geography changed significantly once the war began. In 2020, the highest numbers of border crossings into Ukraine were recorded among citizens of Moldova, Belarus, and Russia. In 2025, Moldova remains the leader in terms of the number of entries, with Romania and Poland completing the top three.

Figure 5. Number of foreigners’ entries into Ukraine in 2020 by country of origin

Foreigners may stay in Ukraine on different legal grounds. Broadly, they can be divided into three main categories:

- Short-term stay – a stay for the period allowed by a visa, or up to 90 days within a 180-day period under visa-free rules. The purpose of travel may be tourism, business, or private visits, and such individuals are not permitted to work during their stay.

- Temporary residence – the most common pathway for labor and study migration. A foreigner receives a temporary residence permit if they have one of the following grounds: official employment, study, participation in international or civil society projects, volunteering, or service in representative offices of foreign companies or organizations. Such a permit is usually issued for one year (sometimes for two to four years) but can be renewed as long as the underlying grounds remain in force. The permit allows for official employment (if issued on employment grounds), residence, movement within Ukraine, and access to certain administrative services. However, it does not grant voting rights, does not equate the foreigner with a citizen, and depends entirely on the continued validity of the underlying grounds.

- Permanent residence – granted to those who obtain an immigration permit, primarily individuals with long-term or family ties to Ukraine: spouses of Ukrainian citizens after two years of marriage, parents of joint children, persons of Ukrainian descent, or those who have invested more than $100,000 in Ukraine’s economy. Unlike a temporary status, a permanent residence permit is valid indefinitely and provides significantly broader socioeconomic rights (such as the ability to work and access free healthcare), though it still does not allow voting or being elected.

Although hundreds of thousands of foreigners enter Ukraine every year, interest in permanent or long-term residence remains modest. According to the State Migration Service, in the first nine months of 2025, 2,384 immigration permit applications were reviewed, and in 2,129 cases, applicants received a positive decision. For comparison, in just two months of 2019, 2,027 cases were reviewed (almost the same volume as in nine months of 2025). In other words, despite public fears, there is no mass “influx” of foreign workers. Most applicants seek immigration permits on family or humanitarian grounds: marriage to a Ukrainian citizen (71% of all permits granted), joint children (8%), territorial origin (7%), Ukrainian descent (6%), or long-term residence in the country (3%).

Among the 306,000 people who hold permanent residence permits, the majority are originally from Russia, Moldova, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, and Belarus (mostly former residents or people with family ties in Ukraine (Figure 6)). However, there is no noticeable influx of new applicants wishing to settle in Ukraine. In the first nine months of 2025, only 2,289 people obtained a permanent residence permit for the first time, indicating that demand for permanent residence in Ukraine among foreigners remains low. This refers not to migrants staying in the country temporarily, but specifically to those who have decided to remain long-term and formalize their status. Labor migration, by contrast, manifests primarily through temporary residence.

Figure 6. Top 10 countries whose nationals hold permanent or temporary residence permits in Ukraine, according to the State Migration Service as of September 30, 2025

As of fall 2025, more than 46,000 foreigners and stateless persons in Ukraine hold temporary residence permits (Figure 6). The largest groups come from Azerbaijan, Turkey, Moldova, India, Uzbekistan, the United States, China, and Israel. Of these, more than 10,000 foreigners are officially in Ukraine for employment, another 7,000 for study, and roughly 5,000 for volunteer or civic activities. These are targeted and regulated flows rather than a mass influx. Among labor migrants, the majority are executives and managers: one in three holds a managerial position or is developing a business in Ukraine. At the same time, since 2022, the number of those coming to volunteer or work in civil society organizations has increased.

Attracting migrants is challenging primarily because of the risks they face themselves. The war continues, even the deep rear does not guarantee safety, and the economy is still unable to offer wages competitive with those in EU countries. Additional barriers include cultural differences, language barriers, and the lack of stable integration programs. For many foreigners, Ukraine becomes more of an intermediate stop – a launchpad for moving onward to the EU labor market. Ukraine is not yet a magnet for labor migrants: neither in terms of wages, nor safety, nor quality of life. So fears that Ukraine will be “overrun by waves of migrants” are exaggerated. It is more realistic to speak of the gradual development of a more open yet still regulated labor market.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations