Like Ukraine’s Armed Forces and state institutions, the hromadas and local authorities demonstrated resilience in the first year of the full-scale war. Local self-governments adapted to various types of shocks and implemented unique programs and policies, occasionally making mistakes and encountering problems. All this experience is valuable for the further development of resilience at the local level. We documented this in our study “Governance processes and the territorial hromadas’ resilience to wartime challenges.” In this article, we want to highlight some issues and practices for ensuring such resilience.

The study by the KSE Institute’s Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development under the project “Stimulating Civil-Military Partnerships to Build Ukraine’s Resilience in the Face of Russian Military Aggression” was conducted in September-December 2022 at the initiative of the Ukrainian Territorial Defense Forces Command with funding from the Hanns Seidel Foundation in Ukraine. The findings of the full analysis of civil-military cooperation were not made public but handed over to the command of Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces. However, the Center prepared a report for local self-government bodies and other stakeholders presenting challenges and best practices in the governance processes of forecasting and responding to crises caused by the full-scale war in Ukraine at the local level.

The research participants defined resilience as the cooperation of actors at different levels, unity, competence, proactivity, adaptability, and viability.

In the study, we focused on the governance processes of local self-government bodies because, as in-depth interviews showed, most stakeholders viewed governance problems as a challenge to further development of resilience in their hromadas. We selected the following governance processes for analysis: “Strategic thinking of threats and response plan,” “Communication,” and “Coordination of efforts (cooperation).” These processes are often mentioned in the literature on ensuring resilience at the regional and local levels (Reznikova, 2022). You can read more about governance processes and resilience in Appendix 1.

Table 1 shows the possible tasks contained within these processes during crises (the list is not exhaustive):

Table 1. Processes and tasks

| The strategic thinking of threats and response plans | Communication | Coordination of efforts (cooperation) |

|

|

Ensuring cooperation and effective communication:

|

Source: compiled by the author

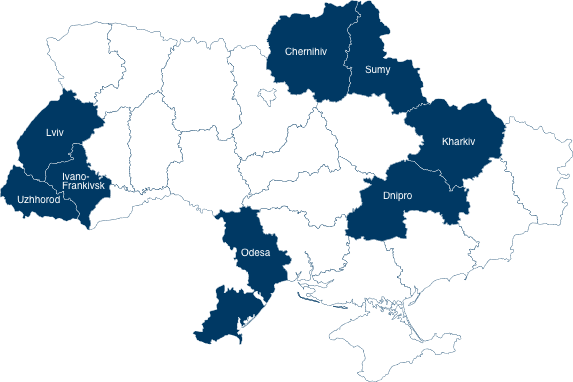

Materials of 75 in-depth interviews and eight strategic sessions with representatives of local self-government, local state agencies, volunteers, and organizations involved in resilience development and crisis response activities due to the full-scale russian offensive became the basis for identifying problems and best practices. The interviews and strategic sessions were held in three types of urban hromadas: those in the rear (Lviv, Uzhhorod, Ivano-Frankivsk), near the fighting front (Dnipro, Odesa), and borderline/de-occupied ones (Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Sumy). The FAMA research agency conducted the in-depth interviews.

Over 100 participants

representatives of local self-government, state agencies on the ground, volunteers, and representatives of organizations involved in developing resilience and response to crises due to russia’s full-scale offensive

75 in-depth interviews were conducted with the main stakeholders to gain insight into resilience in cities and regions

During the team’s work, a series of massive shellings across Ukraine, blackouts, and constant water supply and heating emergencies occurred. This created a unique opportunity to study the actors’ adaptation practices and responses to new crises as they emerged and explore how different stakeholders adapted to new realities in live time mode. The processes described in Table 1 are discussed in more detail below.

Problems and successful practices in governance processes

The strategic thinking of threats and response plans

Thinking through possible crisis scenarios (foresight) and responding to them is crucial for coordinating the actions of local services, authorities, and hromadas as a whole in the event of a crisis. Although crisis response is necessary, it risks being short-sighted without prior preparation and might lead to new crises [1].

During the research period, crisis response to problems dominated among the challenges mentioned by the respondents in the hromadas. In another study [2] by the Center for ULEAD, representatives of local government organizations within hromadas had to choose “skills that executive body employees lack in dealing with challenges currently facing the hromada.” 48% of respondents chose strategic planning as such a skill. In the same study, the following issues were mentioned most frequently during interviews:

- No or insufficient level of risk assessment and thinking through event scenarios

- The authorities’ and other structures’ non-systematic approach to preparing for possible threats before and after the beginning of the full-scale war (especially concerning energy infrastructure security, civil safety, and cyber security issues)

These problems are confirmed by survey data for smaller hromadas in the study “Research Cohesion and Decentralization in Ukraine” within the framework of “Support to Decentralization Reform in Ukraine (UDU U-LEAD with Europe)[3].” Thus, most hromadas conducted preparations for possible wartime challenges already after the start of the full-scale invasion or did not conduct them at all. By the war’s 10th month, more than 50% of the surveyed hromadas had not yet adopted national resistance plans at the local level, with only a third fully backing up the hromada-related data.

Only a few hromadas where interviews and strategic sessions were held conduct preparations for possible risks based on crisis planning practices and future challenges. This includes reintegrating veterans, creating methods for integrating IDPs into the hromada, and preparing alternative sources of electricity in the housing sector.

What should hromadas do?

The hromadas’ priority tasks in response to the challenge of a lack of strategic thinking of threats and response plans are:

- Forming a common understanding of risks for a particular area

- Compiling and constantly updating the risk registers

- Determining response priorities

- Forming action plans on the part of law enforcement services, police, local authorities, and other agencies

It is also worth starting to study global experience in developing resilience, threat planning, and cooperating with institutions in other countries, as was done in Lviv at the end of 2021, ensuring that critical infrastructure functions at critical moments [4].

Thus, a coordination group for the development of resilience was created within the Lviv City Council to counteract possible threats. Supported by the British Embassy, The York Emergency Planning College (EPC) and NSDC Lviv became a pilot city for cooperation in implementing resilience planning. The Resilience Program for the city was developed, and the working group underwent training in York (UK), where the Emergency Planning College is located (one of the four UK institutions where local government workers learn to respond to extreme situations in their hromadas).

The result of activities related to the planning of challenges within the hromada should be recorded in strategic documents and worked on with the hromada self-government bodies responsible for resilience. If a hromada cannot develop such an experience, it should cooperate with neighboring hromadas and seek external expertise.

Besides Lviv’s cooperation with the EPC, the practices of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Great Britain, with their respective safety districts and resilience forums, can be of interest [5]. Security districts are a public governance format designed to effectively respond to emergencies at the local level, which involves combining the capabilities of several territorial hromadas and creating a joint governance body and legal regulation. The unification takes into account the category of their characteristic risks and threats and the peculiarities of the security environment in a particular territory of the country, as well as on its borders with neighboring states.

Local resilience forums are regular interagency meetings involving representatives of local government, civil society, mass media, etc., to plan and prepare for emergency situations. Local resilience forums meet at least once every six months.

According to the respondents, the best practices in their hromadas were documenting the hromadas’ experience during the full-scale invasion of Chernihiv (especially in the hromadas that survived the occupation or the active hostilities phase), checking for the duplication of similar plans/measures between different bodies, and developing measures to prevent emergency situations.

The report provides more examples and best resilience practices applied by hromadas.

Communication

Communication is essential to ensuring quality public governance when communication channels are established, and there is trust for dialogue and discussion (Coffey International Development, 2007) [6]. Hromada authorities must respond quickly to threats and crises in wartime and communicate action algorithms. Therefore, communication availability, its effectiveness (format and channels), and the residents’ trust are vital here.

Research participants, who are not part of the authorities, noted the problem of lack or insufficient information about threats and action algorithms/instructions should an emergency occur. Although some algorithms and instructions could be found on hromada websites, their presence was not reported in any news or social media posts. Therefore, local government communications with the population are not effective enough. Local authorities must review the communication format with the people regarding crises and channels of information dissemination.

The population’s resistance to informational attacks and influences is no less a problem in hromadas. Interview participants often mentioned local residents’ posts about shelling, hitting targets in cities, spreading false information on social networks, etc. This suggests a lack of people’s resistance to disinformation and ignorance of the rules for publishing information in the realities of war.

What should hromadas do?

Many of the crises local authorities inform the public about are typical for hromadas. Therefore, individual hromadas use sample messages created by other hromadas. The report provides examples of local authorities’ cooperation with non-core but popular media in Sumy, creating online maps for generators, and using housing co-ops as a communication channel in Lviv. In addition, the following tips will be helpful to hromada leaders:

- Use publicly available materials from the Center for Strategic Communications and Information Security, which systematically prepares advice on actions in various situations (e.g., preparing for a blackout).

- Create publications like tutorials, short videos, etc., to be distributed on Facebook, Telegram channels, and/or television. However, the traditional options should not be ignored either: meetings with hromada members and the printed press.

- Experience from previous crises (COVID-19) can also come in handy. The manual “How hromadas can tackle challenges and act successfully during a crisis” contains communication rules at different stages of a crisis, crisis communication tools, etc.

- An important aspect is receiving feedback. Local governments need to understand through which communication channels they are more likely to reach out to citizens to use only effective media later.

- “Research Cohesion and Decentralization in Ukraine” within the framework of “Support that Decentralization Reform in Ukraine (UDU U-LEAD with Europe )” shows that about 85% of the surveyed hromadas used Facebook to disseminate information among hromada residents before the invasion. After February 24, this figure increased to 95%. Diversifying communication channels makes addressing a wider range of hromada residents possible. In parallel with publications on the hromada website and in social networks, information about crisis action algorithms should be disseminated through activists and representatives of grassroots initiatives.

Coordination of efforts (cooperation)

In addition to external communications, it is worth highlighting separately internal communication problems. Firstly, there is often poor communication within hromadas between representatives of different structures, resulting in duplicated functions and inefficient resource allocation. Secondly, even with a high level of communication with representatives of various stakeholder groups, there are problems with feedback and taking into consideration their opinion during decision-making.

Interviewees repeatedly mentioned insufficient coordination between various actors/participants of civil-military cooperation. This problem is most pronounced in the hromadas with a lack of cooperation between the authorities and volunteers/hromada organizations due to (1) lack of effective governance, resulting in suboptimal allocation of resources or their waste; (2) lack of trust due to previous corruption scandals, the parties’ misunderstanding the specifics of each other’s work, and non-compliance with the rules.

What should hromadas do?

Institutionalization and networking help tackle the challenge of coordinating different sources of resources and involving active residents.

- Institutionalization, namely building permanent coordination centers, new organizations, or structures under local authorities, helps resolve the main problem of inefficient governance and duplicated processes, leading to the loss of critically needed resources. It should also be remembered that institutionalization requires human governance resources and a financial component. A successful example will be distinguishing between fundraising into projects and fundraising into institutional support.

- Networking will make it possible to attract free resources, relieve managerial functions, or even outsource tasks to other organizations or volunteers. Also, established networks and quick and informal communication between government representatives and activists allows hromadas to effectively maintain resilience to most challenges. Online chats or opinion leaders trusted by authorities and active residents are often used to build such a network within hromadas.

Public recruitment of volunteers within hromadas who can contribute to solving crises is essential. During recruiting, one must check whether the organizations involved are honest.

The Save Ukraine Now coordination center became a successful practice of institutionalization in Ivano-Frankivsk. It was created jointly by the city authorities, the territorial defense of Ukraine’s Armed Forces, and public activists. The center’s key task is to analyze and coordinate aid distribution to localities that require it most. The center provides the local territorial defense units in the combat zones and assists internally displaced persons and other individuals.

An important difference from the spontaneous coordination centers set up in other hromadas is the institutionalization of this center as an NGO and the establishment of the organization’s permanent budget, provided for under cooperation programs with the hromada’s businesses. Business entity employees, including Prykarpattiaoblenergo, transfer one day’s salary for the needs of the coordination fund and the Territorial Defense once a month. The list of organizations supporting this initiative is growing every month.

Conclusions

Building resilient hromadas is a complex and long-term process. Essential steps are the development of a common understanding of the concept of “resilience” and steps to adapt it to the crises realities caused by the war in Ukraine.

In this piece, we tried to briefly describe and focus on the governance processes of local self-government bodies that can be an example of resolving challenges. Without effective practices in the processes of “Strategic thinking of threats and response plan,” “Communication,” and “Coordination of efforts (cooperation),” it is impossible to build a resilient hromada and withstand the existing and potential shocks posed by hostilities and humanitarian and infrastructural crises.

We hope the practices presented in the report will be helpful for implementation by local self-government bodies eager to have such knowledge.

The center plans to continue the series of publications highlighting the best practices for responding to crises in hromadas. If you have practices in your hromada that are worth sharing, please write to [email protected]. You can read more about the practices, a more detailed description, and links to some cases in the full report on the Center’s website.

Appendix 1. Governance processes and resilience

One of the study’s challenges was understanding what the respondents meant by “resilience”. After all, a lack of common understanding can disrupt the development of this hromada component.

The understanding of resilience in the surveyed hromadas is based on the following concepts:

- Cooperation of different actors at all possible levels

- Unity for common victory (no criticizing each other or conflicts between actors)

- Competence and motivation of the personnel in key positions: “everyone doing their job in their place.”

- Proactivity: willingness to take responsibility and make decisions

- Adaptability: the ability to face up to the threats and challenges arising daily

- Viability: preserving/maintaining life within the hromada, which implies a certain level of financial and institutional capacity to implement local projects

Scientific literature (Reznikova, 2022 [7]; Keck, Markus & Sakdapolrak, Patrick, 2013 [8]) and Ukrainian legislation [9] define resilience as the system’s ability to effectively resist threats of any origin and nature, adapt to changes in the security environment, maintain stable operation, and quickly recover to the desired equilibrium after crisis situations. In our research for the ULEAD project, resilience is defined as a combination of adaptation and robustness since recovery is difficult to explore in wartime.

Different understanding of resilience between scientific literature and hromada representatives still shows a gap in the vision of resilience and its components, even in large hromadas at the regional level. This leads to the lack of a unified approach to developing both response practices and metrics measuring hromada preparedness. Without a clear understanding of what resilience is about, there will be no strategy for building it.

The governance practices highlighted in this article are examples of adapting to realities and are uniquely new phenomena for hromadas. At the same time, some of them help keep the pre-crisis processes working in the hromadas. For example, the practice of the generator purchase program, which is new for the hromadas, helps ensure the functioning of the regular water supply services.

Therefore, we believe it is essential to start sharing the hromadas’ best adaptation practices to help them operate more effectively in times of crisis.

[1] Huss, O. & Keudel , O. (2023) What makes Ukraine resilient in an asymmetric war? Presentation at the IERES, George Washington University, 17.01.2023

[2] The research is conducted by the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization and Regional Development. The project materials are to be published in the spring of 2023

[3] The research is being conducted by the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization and Regional Development. The project materials are to be published in the spring of 2023.

[4] See the case description in the report.

[5] You can read more about these formats in Ukrainian in the analytical report “Organization of the system for ensuring national stability at the regional and local levels from the National Institute for Strategic Studies.

[6] Coffey International Development, 2007, ‘The Role of Communication in Governance: Detailed Analysis,’ Coffey International Development, London

[7] Reznikova, O. (2022). STRATEGIC ANALYSIS OF UKRAINE’S SECURITY ENVIRONMENT. Strategic Panorama, 45-53. https://doi.org/10.53679/2616-9460.specialissue.2022.05

[8] Keck, M., & Sakdapolrak , P. (2013). WHAT IS SOCIAL RESILIENCE? LESSONS LEARNED AND WAYS FORWARD. Erdkunde , 67 (1), 5–19. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23595352

[9] DECREE OF THE PRESIDENT OF UKRAINE No. 479/2021 On the decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine dated August 20, 2021 “On the introduction of the national resilience system”

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations