In UN’s fifth World Happiness Report published two months ago, Ukraine was ranked 132nd out of 155 countries, with a score of 4.096 (Norway being in the top position with 7.537 points). In the past year, Ukraine went down 9 places in the happiness ranking, reaching its historical minimum. Thus, Ukraine became the unhappiest country in Europe. But are we really so unhappy, and if so, then why? Or, was this outcome influenced by the ranking methodology?

The World Happiness Report is the most authoritative international ranking measuring happiness throughout the world. The ranking was first published in 2012, on March 20, the International Day of Happiness.

The ranking includes objective indices – GDP per capita and healthy life years – as well as the results of an opinion survey in which the participants had to answer a number of questions about free choice, benevolence (determined on the basis of readiness to make donations), social support (having someone to rely on in times of trouble), and confidence (presence or absence of corruption in government and business). The opinion survey was conducted by the Gallup Institute. In each of the countries, there were one thousand respondents. Gallup conducts such surveys annually.

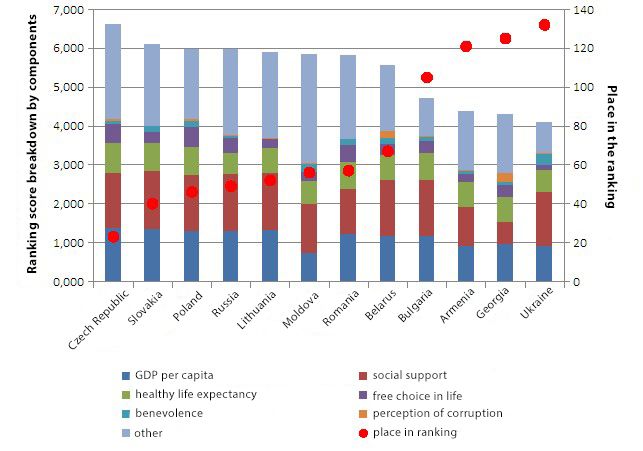

Among European countries, Ukraine is the only one at the bottom of the ranking. Neighboring countries are ranked much higher: Russia is in the 49th place (5.963 points); Poland, 46th (5.973); Belarus, 67th (5.569); and Moldova, 55th (5.838).

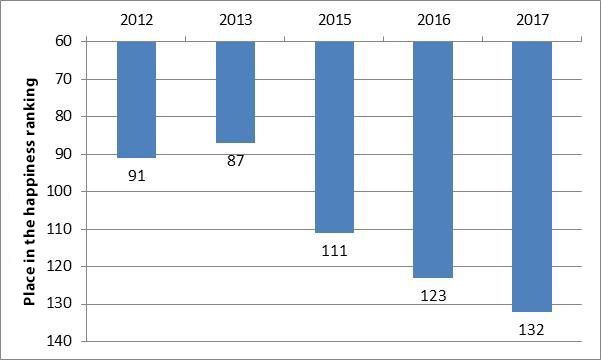

Ukraine’s standing has not always been so low: before 2015, the country was 40 notches higher. However, Ukraine’s ranking has exhibited negative dynamics for three years in a row. In 2012 and 2013, our country was in the top 100 happiest ones; but starting from 2015 (in 2014 the ranking was not published) the country began moving down the ranking: to 111th place in 2015, 123rd in 2016, and 132nd in 2017 (Fig. 1). It should be noted that the number of countries in which happiness is measured has remained more or less the same.

Fig. 1. Ukraine’s happiness ranking in 2012 – 2017.

Data source: UN World Happiness Report.

Gallup sociologists noticed another fact: in the past three years Ukraine’s ranking reached its historical minimum. Moreover, according to Gallup, Ukraine is in the top five of countries with the most negative happiness ranking dynamics in the past 10 years. After comparing opinion survey data for 2005-2007 and 2013-2014, the authors of the report concluded that Ukraine’s happiness index decreased by 0.930 points. Only Botswana, Greece, the Central African Republic and Venezuela recorded greater decreases.

Has everything been lost?

Expert sociologists attribute the deterioration of Ukraine’s position in the World Happiness Ranking to a number of reasons. The first one is the worsening of the economic situation and the ongoing war in the Donbas. The second one consists of Ukrainian society’s greater demands after the Revolution of Dignity.

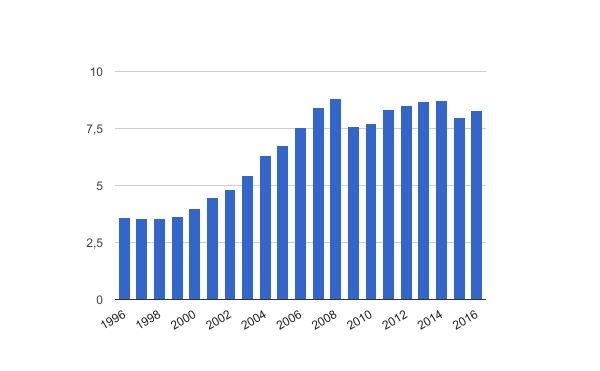

According to the International Monetary Fund, in 2016 Ukraine’s per capita GDP (with regard to Purchasing Power Parity) amounted to $8,305, showing an increase of $310 over the 2015 level, but still remaining among the lowest indices in the region (for example in Russia the per capita GDP is $26,490; in Poland, $27,764; in Belarus, $18,000) – see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Ukraine’s per capita GDP with regard to Purchasing Power Parity in 1996-2016. Data source: IMF.

Second, Ukraine’s place in the overall ranking was influenced by the length of healthy life. This is an index measuring the number of years in which a person can lead a healthy, active life (not to be confused with the average life expectancy at birth). According to the World Health Organization, the average life expectancy in Ukraine is 64.1 years, whereas in Poland it is 68.7; in Romania, 66.8; and in the Czech Republic, 69.4. In countries of Western Europe, this parameter exceeds 70 years. However, this data fails to account for the stark difference between Ukraine’s happiness index and the indices of the ex-USSR countries. In particular, in Belarus the average length of healthy life is 65.2 years (in the ranking, Belarus is 65 places higher than Ukraine); in Moldova, 64.9 years (77 places higher); in Russia, 63.4 years (83 places higher).

However, in the past 15 years the Ukrainians’ healthy life span has increased by four years – from 60.4 in 2000 to 64.1 as of today. Thus, Ukraine’s happiness index could not have been influenced by the dynamics of healthy life length either.

Talking about subjective criteria, the lowest indices were those reflecting free choice in life and perception of corruption. The latter index indicates that the Ukrainians trust neither their government nor business. However, the Ukrainians’ level of benevolence (generosity) is high.

Fig. 3. The rating points broken down into components; a lower index and a higher place in the ranking indicate a worse showing.

What does the ranking really measure?

VoxUkraine asked Ukrainian sociologists for their opinion on the World Happiness Ranking and for their assessment of this year’s outcome for Ukraine.

The sociologists take a cautious attitude towards the UN Happiness Ranking. Yevhen Holovakha, deputy director for research at the NASU Institute of Sociology, says that the UN Happiness Ranking fails to reflect the happiness level: “This happiness ranking reveals the state of affairs in a country rather than how the people really feel. It relates primarily to prerequisites for happiness,” Holovakha says.

According to Ukrainian sociologists, in most countries of the world the list of factors having the greatest influence on happiness is topped by those relating to an individual’s private life: family, health, confidence in the future, financial position, work, and children. Ukraine is no exception, aside from the Donbas, where security is in the first place. There is, however, one more specific feature: unlike the United States, Canada and other “happy” countries, in Ukraine one’s financial position affects the perception of happiness in a directly proportional manner.

“As long as the material level is very low and the people focus on improving their wellbeing, the level of happiness is on the rise [in parallel with the rising standard of living]; but once the basic needs have been satisfied, getting still richer does not lead to greater happiness,” says Iryna Bekeshkina, head of the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation.

Yevhen Holovakha attributes the decrease in Ukraine’s happiness ranking to the deterioration of the economic situation and pessimistic public views of the future. “Even if objective economic indices are improved, people do not always feel better. Therefore, this reveals their lack of confidence in the future,” the sociologist emphasizes.

Volodymyr Paniotto, director general of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, adds that the decrease in the happiness level is due in no small part to mass media. In Paniotto’s view, “political strife, information warfare, and free media make the people feel the situation is worse than it really is.”

Volodymyr Paniotto also notes that the Ukrainians’ very low happiness index is primarily related not so much to direct economic reasons as to the way people perceive the economic and political situation. “Such a big difference – it results from subjective parameters (satisfaction with life in general and different aspects of happiness), which can be interpreted as a fraction, with satisfaction of some or other needs as its numerator and level of aspirations as its denominator. Therefore, this is a specific index.”

Even more so, the sociologist believes that some of the components of the World Happiness Ranking are highly controversial. Comparing Ukraine’s free choice index with that of the Russian Federation, he says that Russia’s high score is wrong: “It’s simply ridiculous that freedom of choice is three times higher in Russia (than in Ukraine – editor’s note),” Paniotto says. “If we had measured it during the Stalin times, it would have been even higher. In a society with no opposition television channels, people are sure that everything is all right with their freedom. Although any [external] observer can see what kind of freedom it is.”

The situation with confidence in government is very much the same, Paniotto says: “In Russia, public trust in government is higher because there are practically no opposition media.”

International sociologists also discuss whether or not this ranking should be referred to as one that measures happiness. Nevertheless, Gallup insists that the ranking can be used to simultaneously evaluate happiness and life satisfaction level. In the opinion of Jon Clifton, managing director of Gallup World Poll, everything depends on the way we perceive happiness. If happiness hinges on evaluation of the living standard on a 0 to 10 scale, residents of Scandinavia will be seen as the happiest ones. But if happiness is interpreted as outwardly exhibited emotions, such smiles and laughter, the happiest people would be those living in Latin America.

A different measure

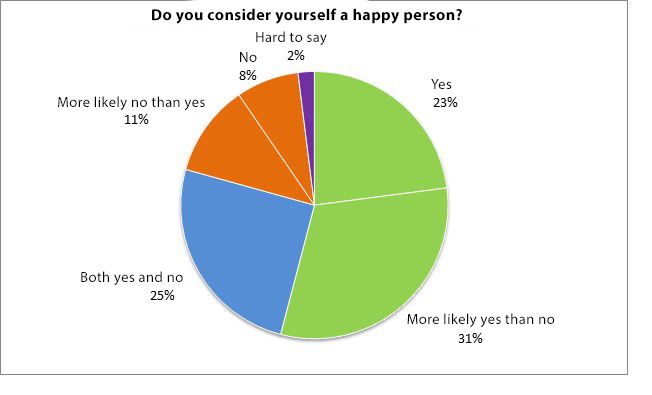

Measurements made by Ukrainian sociologists reveal a radically different picture. In particular, according to the happiness ranking annually published by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 54% of Ukrainians consider themselves to be happy (yes, 23%; more likely yes than no, 31%), while 19% think they are unhappy (more likely no than yes, 11%; no, 8%). Unlike the world ranking, the participants had just one question to respond to: “Do you think you are a happy person?”

Fig. 4: Do you think you are a happy person? (KIIS data for December 2016)

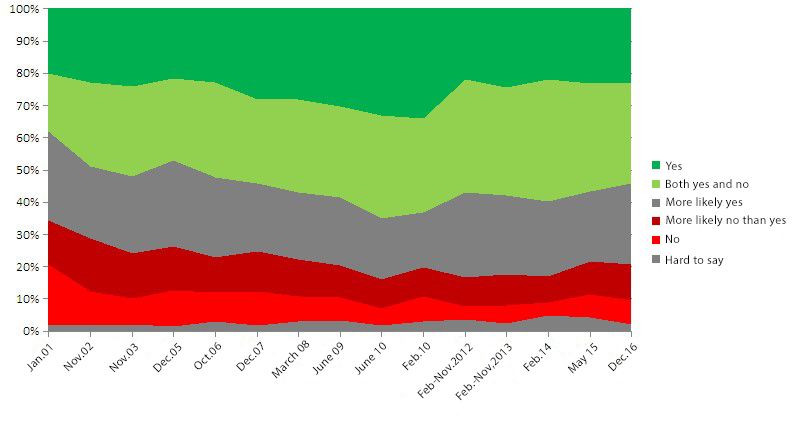

KIIS has been measuring happiness since 2001. During the 17 years, the number of happy Ukrainians increased from 38% to 54%. The current figure is not a record, however: in 2010, 65% of Ukrainian respondents said they were happy. Between 2011 and 2014, the happiness level went down five percent and then it continued to decrease gradually to 54%.

Fig. 5. The dynamics of feeling happy in Ukraine (2001-2016)

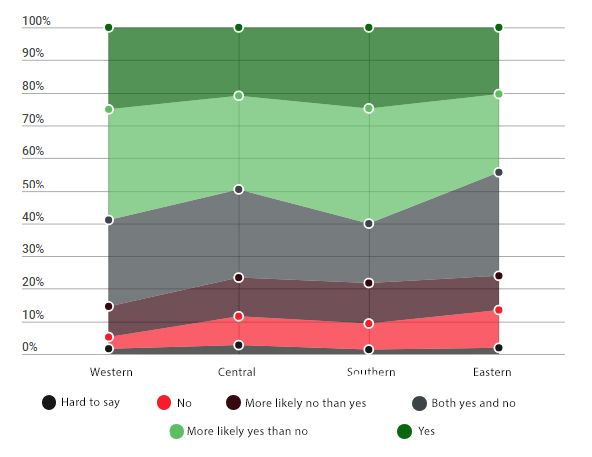

Fig.6. Index of happiness in the regions of Ukraine (data for December 2016).

Volodymyr Paniotto attributes the post-2014 decrease in the level of happiness to mass media liberalization, increased media criticism, and a rising level of societal expectations that are not met because of a lack of effective reforms. “One of the main factors behind the decrease in happiness is greater media freedom. It leads to heavier criticism and rising levels of aspirations and expectations. On the other hand, if there are no fast reforms, or if they evolve slowly, people assume a more critical attitude towards the government,” the researcher remarks.

The decrease in the happiness level may also be related to the rising levels of poverty and stress. Yet this was relevant for 2015, while in 2016 these parameters leveled off. “If the economic and military situation is stabilized, the social situation in the country will gradually improve,” Paniotto predicts.

Life satisfaction ranking

On March 23, Gallup published another ranking, one which identified countries whose residents are most and least satisfied with their lives. As it turned out, satisfaction with life in Ukraine is even lower than the happiness level. Ukrainians were ranked third among countries the residents of which are least satisfied with their lives. Thus, the researchers found that 41% of Ukrainian people are suffering, 50% are trying to survive, and a mere 9% feel good. According to Gallup, the percentage of those suffering is “the highest Gallup has recorded among post-Soviet states.” The level of dissatisfaction with life is higher only in Haiti (43%) and South Sudan (47%).

Within the framework of this survey (which Gallup conducts annually in most countries of the world), the participants are to evaluate their current situation on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being the worst situation (suffering) and 10 being the best one (thriving).

We would also like to mention a few other important conclusions from that survey. Firstly, a solid majority of Ukrainians (57%) believe their life is getting worse. Secondly, nearly half of the country’s population (46%) say that sometimes they do not have enough money for food and for satisfying the basic needs. This is the highest figure Gallup has ever recorded for Ukraine and one of the highest in all Europe.

The only ranking in which Ukraine holds a decent place is the Happy Planet Index. In 2016, Ukraine was 70th among 140 countries, getting 26.4 points out of the possible maximum of 50.

The index measures four parameters: life expectancy, wellbeing, inequality and ecological footprint. In particular, Ukraine was ranked 85th on average life expectancy (70.3 years), 82nd on wellbeing (5 points out of 10), 49th on inequality (17%[1]), and 76th on ecological footprint[2] (2.6 hectares per capita). The main aim of the index is to identify how efficiently people use natural resources for a happy life. The specific methodology of the index is the reason why the index ranking is topped by Costa Rica, Mexico and Colombia, while the least happy countries are Togo, Luxemburg (low ecological footprint index), and Tchad.

Are Ukrainians happy?

Judging by the above indices, Ukrainian citizens can be happy as well as unhappy at the same time. A lot depends on the way happiness is evaluated, on the economic situation, subjective attitudes, etc. The happiness parameter cannot be measured accurately. However, despite the shortcomings of the assessments quoted in the article, these results should not be dismissed, since they can tell a lot about the population’s opinion on the state of affairs in the country.

Notes

[1] This parameter measures inequality among people in terms of length and positivity of life (based on life expectancy and wellbeing index).

[2] The ecological footprint shows the area of productive land and water that the population can use.

Main photo: depositphotos.com / alphaspirit

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations