In times of war, governance tends to become more centralized, top-down, and security-driven (Hart, Rosenthal and Kouzmin 1993, Kyvelou and Marava 2017). Democratic participation is often suspended in favor of executive control (Lasswell, 1941; Desch, 1996; Lowande & Rogowski, 2021).

Yet in Ukraine, despite the ongoing full-scale Russian invasion and the constraints of martial law (Rabinovych et al., 2025), many local governments (hromadas) have continued to involve civil society in crisis response (Keudel & Huss, 2024). Rather than being sidelined, civic actors in many communities have remained engaged in local decision-making, resource coordination, and public service delivery.

This article examines how Ukrainian hromadas have sustained civic engagement in local crisis governance during wartime. Leveraging survey and case findings, we show a clear pattern: collaborative participation can enhance preparedness and help maintain democratic legitimacy even under martial law.

Drawing on survey and interview data from over 180 municipalities, we argue that Ukraine offers an instructive case of collaborative crisis governance – a mode of network-based governance in which local authorities engage other stakeholders to gain resources, knowledge, and coordination capacity to collective problem-solving.

This article draws on the findings of ICLD Research Report No. 33, Local Democracy and Resilience in Ukraine: Learning from Communities’ Crisis Response in War, authored by Oleksandra Keudel, Oksana Huss, Valentyn Hatsko, Andrii Darkovich. We gratefully acknowledge the generous financial and institutional support of the Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy (ICLD), whose funding made this project possible and enabled our collaborative research on wartime local democracy and community resilience in Ukraine.

The full survey dataset used in this research has been published on DiscussData and is ferry available for download

Ukraine’s Decentralization Reform Before and After the Full-Scale Invasion

Since 2014, Ukraine’s decentralization reform has fundamentally transformed local governance. The reform transferred key responsibilities—budgeting, public services, and local development—to newly amalgamated municipalities (hromadas), giving them greater autonomy and financial capacity. This shift fostered a more responsive and participatory model of governance and created institutional conditions for collaborative practices between local authorities, civil society, and businesses.

However, the introduction of martial law due to Russia’s full-scale invasion has led to changes in the areas of responsibility of local self-government (LSG). Emergency coordination, defence logistics, and civil protection were partly recentralized, and regional state administrations were converted into military administrations with expanded authority. Military personal income tax, a growing share of local budgets in affected areas, was reallocated to the national level. In frontline areas, 13% of hromadas now operate under military administrations, heads of which are appointed by the president.

Despite these constraints, the suspension of elections, and many challenges in public informing and engagement (Figure 1), local governments have remained key actors in wartime governance. They continue to maintain public services, coordinate humanitarian aid, and support displaced populations.

Figure 1. Challenges of public informing and engagement initiatives at times of war

Source: Authors’ own survey

Note: N = 129 (LSG with any initiatives to inform and/or engage citizens or businesses in the past 12 months). Question: In the initiative mentioned above, to inform or engage citizens that you have implemented, what challenges did you have to overcome during the implementation process? Options: hard to overcome; easy to overcome; the challenge was not overcome; not relevant.The figure shows “hard to overcome” and “easy to overcome” responses. Challenges that were ‘hard to overcome’ for 30% and more respondents are highlighted.

Methods

This analysis draws on original survey data[4] from 181 local governments collected between January and March 2024, complemented by interviews, focus groups, and a validation workshop with public officials and civil society actors. The survey was conducted as an online questionnaire, distributed via nation-wide local government associations and NGOs. We received one response per municipality; if more than one official replied, we used the response from the highest-ranking respondent. Respondents were mainly mayors and deputy mayors, with heads of local government units as the next largest group. About 14% of Ukrainian municipalities in government-controlled areas participated in the survey.

To analyze changes over time, we compare results with three earlier studies conducted in 2021[5], 2022[6], and 2023[7]. These previous studies included questions on preparedness, vertical coordination, public engagement, and digital communication, many of which were repeated, sometimes in a slightly different form, in 2024.

Figure 2. LSGs surveyed by region

Source: Authors’ own survey. Note: This study faces a sampling constraint: Zaporizhzhia oblast is over-represented because we could not survey de-occupied or frontline hromadas in Kherson, Luhansk, and Donetsk. To reach those areas, we partnered with the NGO People in Need, whose activities were then concentrated in Zaporizhzhia. This NGO helped us distribute survey to the leaders of de-occupied hromadas and those near frontlines. The collaboration helped us manage survey fatigue and counter the low priority that frontline hromadas understandably give to research amid daily challenges

Collaborative Crisis Response: Community Members as Partners

Legitimacy Pursuit Through Public Engagement

Rather than retreat from the public, many Ukrainian local governments have actively involved community members in wartime crisis response. These efforts go beyond basic service provision and reflect a broader strategy of coproduction where authorities and societal actors jointly shape crisis responses. Under martial law, when elections are suspended, this engagement serves as an alternative source of democratic legitimacy.

Survey data from 2024 show that 71% of LSGs reported informing and/or engaging residents or businesses in the past year. This share remained stable even in areas experiencing active hostilities (69%) or those that were liberated (64%). At the same time, more local governments reported involving stakeholders directly in problem-solving (76%, 2.2 percentage points more than in 2022) and including diverse opinions (78%, 13 percentage points more than in 2022) (Figure 3). These trends suggest that deliberate civic participation is increasingly used as a tool for democratic resilience, functioning as an alternative pillar of legitimacy and accountability in the absence of elections.

Figure 3. The purpose of wartime public information and engagement initiatives by LSGs in 2024 compared to 2022

Source: Authors’ own survey. Note: N 2024 = 129, N 2022 = 160 (for LSGs that have initiatives to inform and/or engage citizens or businesses); the question was: “For what purpose did the LSG in your community introduce initiatives to inform and/or engage citizens or businesses in the last 12 months?” Respondents indicated primary and secondary purposes, as well as those that were irrelevant. The figures show only primary purposes.

One striking example comes from Makariv in Kyiv Oblast, a village that was massively damaged in the early days of the full-scale war. Rather than centralize postwar planning, the local government involved the whole community—including political opposition figures—in urban development workshops. Over time, these deliberations led to the formation of a “community development council“. This is an informal group which includes opposition parties and local government council members. At the council meetings they, with the assistance of NGOs, discuss projects in hromada such as creation of a Veterans’ hub.

Another form of collaboration emerged around the integration of internally displaced persons (IDPs). Over 750 local and regional governments have established IDP councils—advisory bodies that include both officials and displaced residents or their representatives. They serve as a communication channel between local authorities and displaced residents, helping to identify needs, share available support options, and coordinate responses. They represent a form of protected consultation—a meaningful participatory practice within the limits imposed by war.

Coproduction of Solutions to War-Related Problems

Local governments have increasingly adopted coproduction during the war—not just consulting civic actors but collaborating with them in designing and implementing responses.

This engagement was primarily motivated by practical needs: to build up community resources (85%), meet the needs of vulnerable social groups (88%), and coordinate the supply and demand for aid, including assistance for internally displaced persons (IDPs) and the Ukrainian military (85%) (Figure 3). Compared to 2022, there was a marked increase in efforts to include diverse opinions (+13 percentage points), while activities related to mitigating emotional pressure and fear (–21 pp) and coordinating volunteers (–20 pp) declined. This shift reflects a move toward more structured and targeted forms of collaboration focused on delivering immediate assistance.

The most common area for engagement was the integration of internally displaced persons (IDPs), with 34% of LSGs identifying it as the most critical issue addressed jointly with stakeholders. Other areas included civilian defense and security (21%) and provision of basic necessities (17%). In nearly all cases, LSGs informed at least one stakeholder group when addressing a critical issue. At the same time, only about a fifth of all respondents reported no engagement across the other three dimensions of participation—consultation, dialogue, and partnership—suggesting that collaboration is a widespread mode of crisis response.

The findings expose a latent governance informing deficit: roughly one-quarter of hromadas (25%) did not inform citizens about the latest critical issue in hromada. Addressing this communication shortfall could catalyze higher levels of institutional trust and unlock additional local resources essential for tackling critical problems within these communities.

Figure 4. Extent of stakeholder engagement in response to critical war-related local problems

Source: Authors’ own survey. Note: N = 127 (LSGs outside of combat areas, LSGs in combat areas, and liberated LSGs that engaged the public and/or business on critical issues over the last 12 months); the question was: “Regarding the problem you identified in the previous question, which stakeholders were involved, and how did they participate in solving the problem?”

Particularly since 2022, collaboration with IDPs has expanded (Figure 4). LSGs have proactively shared information and regularly consulted IDP groups, often with support from NGOs acting as facilitators. These intermediaries help communicate needs and guide local authorities in adjusting programs. Although responsiveness to stakeholder input varies, the increased reliance on this form of engagement reflects a growing appreciation for grassroots knowledge in problem-solving.

NGOs and businesses also play crucial roles in collaborative crisis governance. NGOs have helped create inclusive infrastructure, such as community centers and bomb shelters. A notable example of institutional cooperation between local government and business is the UNBROKEN rehabilitation initiative in Lviv. It is jointly managed by the Lviv IT Cluster, the Ukrainian Catholic University, and the city government. Together, they coordinate activities and fundraising, ensuring transparency and shared responsibility.

Finally, 10–15 percent of LSGs indicate that they inform or consult former soldiers about issues beyond veteran policy. For example, Makariv specifically contacted the local veteran society during reconstruction discussions. This reflects how LSGs are sensitive to the composition of their communities and understand the significance of veteran inclusion for social cohesion.

Public Engagement Supports Crisis Preparedness

We tracked hromada preparedness at three moments of the full-scale war—February 2022, October 2022 and March 2024—using a 0-to-1 index (where 0 = absolutely not prepared and 1 = fully prepared; see Appendix for details). In the first days of Russia’s full-scale invasion, almost 80% of local self-governments fell into the “low” red zone (score < 0.25; Figure 5), i.e. they were completely unprepared to deal with the invasion. Eight months later, this group had nearly disappeared, replaced by a surge in hromadas with moderate (0.25-0.75) and high (> 0.75) readiness. By March 2024, roughly 70% of hromadas clustered in the moderate band, while the share of the highly prepared group declined to about one-third, signalling a plateau.

Figure 5 illustrates this dynamic: the red curve collapses (low preparedness), the orange curve (moderate) rises steadily, and the green curve (high) forms a “hill”—a sharp climb through 2022 followed by partial retreat in 2024. In simple terms, communities rapidly closed the most critical gaps, but are now settling into a sustainable, although still incomplete, level of readiness.

Figure 5. Distribution of hromadas by Preparedness Index. Comparison February 2022, October 2022, and March 2024

Source: authors’ calculations

Note: In February and October 2022 data come from the survey within the framework of the Project “Support to the Decentralisation Reform in Ukraine” (U-LEAD with Europe): N = 131 (all LSGs except those that are temporarily occupied). March 2024 data come from ICLD survey: N = 156 (LSGs outside combat areas, on the territory of hostilities and liberated LSGs). Information on February 2022 was retrospectively asked in October 2022.

Disaggregating the data adds a nuance. Urban and densely populated hromadas are significantly better equipped than rural and smaller counterparts. This underscores how resource availability and institutional capacity influence crisis resilience.

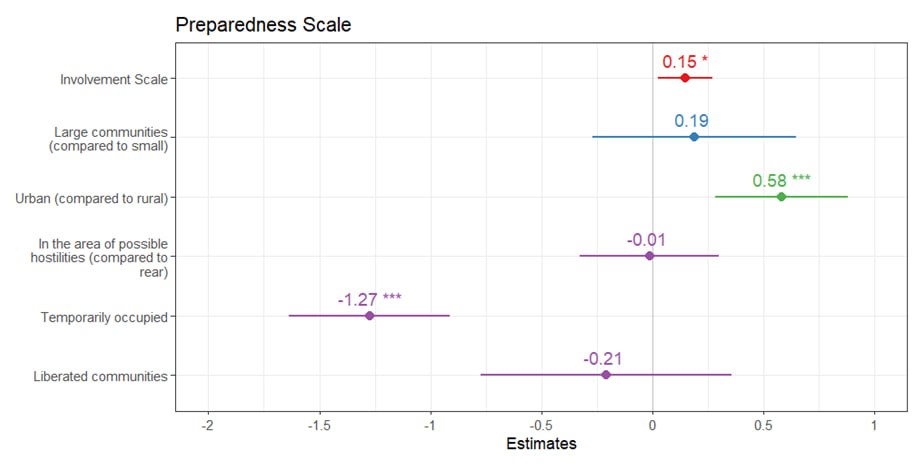

Furthermore, our regression analysis shows that local governments engaging a broader range of stakeholders are better prepared to manage wartime crises (Figure 6). Our preparedness index measures key components of crisis capacity: emergency action planning, readiness to address critical resource shortages (e.g., food, water, medicine), and the ability to restore vital infrastructure. Even when controlling for contextual factors, higher levels of stakeholder involvement are associated with higher preparedness scores.

The likely mechanism behind this relationship is that non-governmental actors help local authorities mobilize resources and co-develop crisis response strategies. This makes engagement not just a democratic practice, but a functional tool of resilience governance.

Figure 6. Standardized regression estimates of nongovernmental stakeholder impact on crisis preparedness

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note. The Involvement Index has a positive and statistically significant effect on preparedness (β = 0.149, p = 0.016). For example, a 10-point increase in involvement (on a 0–35 scale) is associated with a 0.22-point rise in preparedness (on a 0–1 scale), implying that highly engaged hromadas are over 20 percent more prepared than those with minimal stakeholder engagement. The model explains 35.6 percent of the variance (R² = 0.356, n = 181). Control variables include hromada size, hromada type, and security conditions.

Yet, not all local governments make full use of this approach. Only about one-third of those surveyed said they involve NGOs and businesses in planning their crisis response. Since this kind of collaboration helps improve preparedness, it remains a missed opportunity for many hromadas. Increasing civic engagement—especially with support from international donors and national programs—can help strengthen local crisis response in the long term.

Our findings also point to a second important factor: the availability of community spaces. Our data show a positive correlation between the number of physical or discursive spaces in a hromada and the extent of stakeholder involvement (Figure 7). In short, the more accessible public spaces in hromada are, the more likely it is to involve diverse actors in crisis response.

This finding supports our earlier results. It shows a positive link between the availability of physical and virtual community spaces in a hromada and its ability to prepare for wartime challenges. These spaces help local governments and communities work together more effectively. The most common examples in our sample are humanitarian aid hubs, IDP councils, and youth centers. Other spaces include IDP support centers, volunteer hubs, meeting places for civic groups, adult education centers, and business support centers.

Figure 7. Availability of community spaces and stakeholder engagement in war-related problem-solving

Source: Authors’ calculations. Note: The figure shows a scatter plot of the Spaces Index against the Involvement Index with category-wise trend lines (IDP integration—Spearman’s rho = 0.40 [p = <0.01]; other—Spearman’s rho = 0.23 [p = <0.05]); N = 127 (LSGs outside of combat areas, LSGs in combat areas, and liberated LSGs that engaged the public and/or business on critical issues over the last 12 months); the Involvement Index reflects the diversity of involved stakeholders in the multiplicity of participatory dimensions, while the Spaces Index demonstrates the number of community spaces reported by LSG respondents.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Ukrainian case shows that collaborative crisis governance is both possible and effective under wartime conditions. Despite martial law, institutional disruptions, and active hostilities, many local governments have engaged civic actors—NGOs, IDPs, businesses, and veterans—not only as aid recipients but as co-producers of crisis response. This engagement has supported societal resilience by improving emergency planning, resource coordination, and local legitimacy.

To build on these strengths, three recommendations emerge:

- Treat local governments as strategic partners in national crisis management. Hromadas can provide local, context-specific solutions. To support this, Ukraine should develop formal feedback mechanisms and multi-level coordination platforms linking LSGs with oblast and central authorities.

- Make civic engagement crisis-ready. Invest in joint emergency preparedness exercises involving local officials, civic leaders, NGOs, and businesses before the next shock hits. It also requires decentralized resource stockpiling, where local actors help identify, store, and manage emergency supplies.

- Enable participation through investment in civic infrastructure. This includes safe and accessible community spaces such as bomb shelters and inclusive public centers, support for trained facilitators to guide multi-level dialogue, and outreach through new communicators—like youth groups and local NGOs—especially where local governments are overstretched.

Appendix

The Preparedness Scale is a composite measure assessing LSG crisis readiness. It includes 26 items covering resource stockpiles, crisis communication, backup infrastructure, response planning, and data security. The scale’s reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.84), ensuring internal consistency. To facilitate interpretation, the index was normalized from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate greater preparedness.

The Involvement Scale measures stakeholder engagement in local crisis management based on the Council of Europe’s participation dimensions. It includes 35 items (α = 0.87), capturing informing, proactive, and reactive consultation, regular exchange and feedback to stakeholder input (dialogue) across the following stakeholder groups: residents, businesspeople, NGOs, IDPs, veterans, and experts. The scale is an additive index summing all stakeholder interactions, normalized to enhance comparability.

For further reading, see Keudel, O., Hatsko, V., Darkovich, A., & Huss, O. (2024). Local Democracy and Resilience in Ukraine: Learning from Communities’ Crisis Response in War (Research Report No. 33; p. 57). Swedish International Centre for Local Democracy.

[1] Valentyn Hatsko is a data analyst at the Kyiv School of Economics and a PhD candidate in sociology at Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv.

[2] Andrii Darkovich is a researcher and local governance expert at the Center for Sociological Research, Decentralization, and Regional Development at the Kyiv School of Economics Institute. He is pursuing a PhD in political science at the Kyiv School of Economics.

[3] Oleksandra Keudel is an associate professor at the Kyiv School of Economics. She studies democratic transformation and societal resilience in hybrid regimes, specializing in Ukraine’s subnational politics.

[4] Valentyn Hatsko, Antonii Karakai, Andrii Darkovich, Oksana Huss, Oleksandra Keudel (2024). Local Governance in Ukraine during the full-scale Russian invasion. Merged data from online surveys of local self-government authorities

[5] Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. (2023a). Baseline survey on Open Government at local level in Ukraine: Mapping initiatives and assessing needs. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/open-government-surveyeng/1680a97942

[6] Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. (2023b). Survey on the needs and priorities of local authorities of Ukraine. The provision of services in times of war and post-war recovery. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/1680a9f1fe

[7] Rabinovych, M., Brik, T., Darkovich, A., Savisko, M., Hatsko, V., Tytiuk, S., & Piddubnyi, I. (2023). Explaining Ukraine’s resilience to Russia’s invasion: The role of local governance. Governance, 1(20). https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12827

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations