The international assistance to Ukraine is booming. According to the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, during the last two years the amount of grants and technical assistance reached almost $1 bn. This is 1.5 times less than what Ukraine had received in 2008-2013. Moreover, since Maidan, international financial organizations have provided $3.5 bn of loans at a tiny interest rate to Ukraine. Is Ukraine using these huge resources effectively? “(Your) country does not need to ask for extra money, as what had been provided before, has not been used,” – said recently the head of the EU Delegation to Ukraine Jan Tombinski. What prevents Ukraine from successfully cooperating with foreign donors?

A boom amidst the chaos

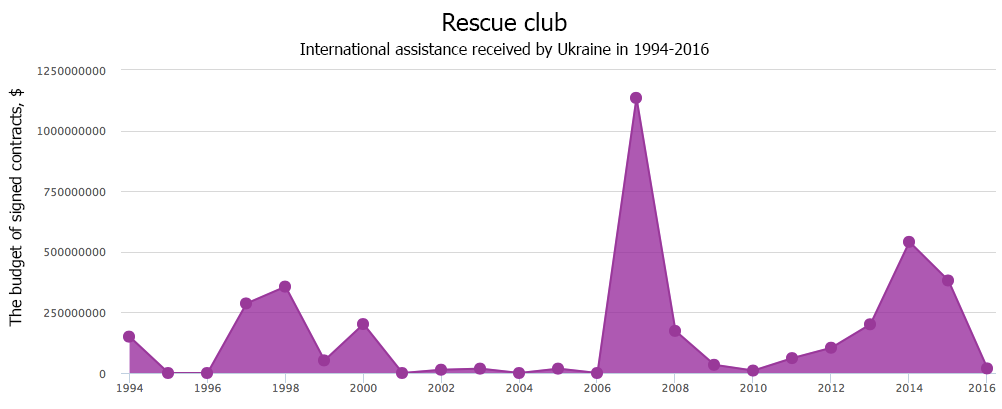

Olena Tregub, the director of the Department for International Programs Coordination at the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, has been very busy recently. The Ministry has registered 133 donor projects amounting to $920 million in the last two years (data provided by the Ministry, calculations by VoxUkraine). The non-repayable aid comes in the form of money grants or assistance by experts and consultants. Only 2007 was more fruitful, mainly due to securing $1.1 bn for the “Chernobyl New Safe Confinement” project. 302 projects of international assistance are being implemented in Ukraine. Their total budget is equal to $3.7 bn. The launch of some projects dates back to the early 1990s (see Picture 1 for a breakdown by years).

Is $1 bn in two years enough or too little? According to the OECD, Ukraine ranked 45th among the top-50 recipients of international assistance (see the OECD “Development aid at a glance statistics by region, Developing countries” report, page 15). In 2014, Afghanistan, Vietnam and Syria were the top-3 recipients of international assistance. Together, they received more than $13 bn. However, Ukraine ranks second among the developing countries in Europe, beaten only by Turkey. Ukraine received $1.4 bn in 2014, which accounts for 16% of all the assistance the region received that year (see the OECD “Development aid at a glance statistics by region, Developing countries” report, page 2). This is twice as much as what the country received in 2013.

Why are the OECD numbers considerably larger than the Ministry’s figures? Firstly, the OECD takes not only grants and technical assistance into account, but all those development loans from international financial institutions (IFI) which include a grant element as well (must be more than 25% of the loan principal, you can find the relevant calculator on the IMF’s site). The Ministry does not keep track of loans provided by IFI. Secondly, not all grants are registered by the Ministry. According to Tregub, the Ministry does not register 30-40% of projects. It mostly records large grants and those grants that need special VAT or custom duty treatment.

Thirdly, no agency in Ukraine has a unified database of all international assistance projects in the country. The OECD records the total budget of projects in each country, requesting the data directly from donors, but it does not break them down separately by projects. The Ministry of Economy stores hundreds of volumes with the detailed information on donor projects, but those data are not digitalized or aggregated. There is also a digital database of projects which was funded by the UNO development program in 2012-2013 (Development Assistance Database to Ukraine). However, the data are outdated. Olena Tregub promises to launch OpenAid soon, a new portal with a database on international assistance to Ukraine.

Tellingly, it is international donors who are paying for the development of the international assistance online platform. The Ministry is not alone in this respect. In the last 1.5 years, many projects within the Ukrainian civil service have been financed in this way. Donors have helped almost all Ukrainian government agencies. They pay salaries to advisers of ministers, hire experts to draft laws, consult bureaucrats, and pay for their attendance of workshops in Ukraine and abroad. One of the most successful reforms – the Prozorro system of public procurement – was implemented as a donor project of German Transparency International, GIZ and other donors. As of today, Prozorro has raised more than $750,000. To a great extent, it is run by volunteers. The web site development for the Ministries of Finance and Infrastructure was sponsored by GiZ and the Renaissance Foundation (funded by George Soros). The National Reforms Council and the Business-Ombudsmen rely on funding from several EBRD member countries, while the Bank itself coordinates the support.

These projects are relatively small-scale. They require several hundred thousand dollars at most. Financing a salary fund for civil servants is quite another matter (the idea gained prominence in autumn of 2014). The EU was ready to invest €96 million into the fund and to pay the salaries of Ukrainian top-officials (ministers, deputy ministers, heads of key departments etc.) in the next few years. A year and a half have since passed and the fund is still not there.

The EU requested a strategy for reforming the civil service which would foresee the sources for its further funding. The Minister of the Cabinet of Ministers was responsible, yet the document he provided was of a very low quality, said the advisor to the Minister of Infrastructure Andrey Motovilovets.

The EU directed the funds to the decentralization project instead. This failure hurt the plans of reform-minded ministers; e.g., the former minister of infrastructure Andriy Pyvovarsky cited his inability to guarantee proper salaries to key employees as a reason for his resignation.

Low state capacity

What happened to the idea of establishing a salary fund for Ukrainian civil servants is a typical example of donor aid projects in Ukraine. Projects are stuck or cancelled simply because the officials in charge do not want or are not able to carry them out. Both the EBRD and the World Bank admit that there have also been numerous cases of intentional sabotage by civil servants.

Low institutional capacity is another problem. Its severity is recognized not only by donors, but by government officials as well. Bureaucrats often lack the skills and expertise that are needed to work with donor aid projects.

As a result, some projects never come into being, laments Christina Danielsson, the SIDA development agency head.

The third problem lies in the government instability and high staff turnover within the Cabinet of Ministers and state-owned companies. Klavdia Maksimenko, the senior manager of the portfolio of World Bank projects in Ukraine, is barely encouraged by yet another change of the government. Much water will flow under the bridge until each ministry appoints a new official responsible for cooperation with donors.

The coordinator is (not) necessary

Sitting in a small room with shabby walls on the ninth floor of the government residence, Olena Tregub looks like Don Quixote who is courageously fighting against the windmills. Launching the Open Aid – an international assistance online platform – is just small part of her plans. Her ultimate goal is to establish a single coordinator of international aid to Ukraine. All grants, technical assistance, international financial assistance loans would have to go through it. The coordinator would also monitor the efficiency of all projects.

Olena Tregub explains,

The countries that receive donor aid are usually so poor and institutionally weak that they are not able to understand and analyze what assistance they get, why they need it, how efficient those projects are and what assistance they really need.

Tregub argues that Ukraine is not using grants and loans efficiently. While grants are relatively small and do not have to be repaid, loans can amount to hundreds of millions of dollars. Even though the interest is small, the Ukrainian Treasury still has to repay the principal.

Lenders, borrowers and the Ministry of Finance usually lack a critical approach when it comes to the choice of donor projects. International financial institutions aim at issuing as many loans as possible. The MinFin aims at getting as many cash to flow in Ukraine as possible. Borrowers want to spend the money. Nobody is actually worried by how it affects Ukraine, explains the Deputy Minister of Economy Max Nefyodov.

As an example of the inefficient use of loans, Olena Tregub cites the joint project of the World Bank and the Ministry of Social policy “Social Assistance System Modernization“.

The project was expected to simplify the process of filing documents and paying benefits to socially vulnerable people. The plan was to spend about half of the loan ($99.4 million) on the re-equipment of local labor offices. The other half was to be spent on creating an informational and analytical system of social protection, which was supposed to unite the disjointed databases of the Ministry of Social protection.

The project, which started in 2006, had to end in 2008. However, it finished 5 years later than originally planned, while the system did not come into being at all. However, local labor offices were indeed reconstructed, re-equipped and its staff was trained. According to the World Bank, this project substantially increased the productivity of employees. Klavdia Maksimenko argues,

Ukraine wouldn’t be able to cope with the huge flow of social benefits to internal refugees and recipients of energy subsidies.

She believes that numerous delays within the Ministry of Social Policy prevented the launch of the information system. However, the World Banks is not shirking from responsibility. Its report admits that the Bank overestimated the ability of those responsible for such a large project. It underestimated the lack of skills the staff had in the area of procurement under international standards (they had to be trained separately). Finally, it did not pay enough attention to the low numbers of the Ministry’s staff that was actually involved in the project and their lack of relevant experience. The Bank also launched a special investigation and found traces of fraud and corruption (look p. 20, it. 42 of the report).

The World Bank is currently implementing a new social protection project with the budget of $300 million, which is aimed at fighting poverty in Ukraine. The World Bank hopes to finally launch the information system for the Ministry of Social Policy.

Tregub is not satisfied at all with such an approach to loan projects.

There is a danger that millions of dollars are going to be wasted instead of being invested. Ukrainian citizens will be the ones to pay them back.

This is why she argues for the need of creating the national coordinator. Such an agency would decide whether Ukraine needs a given international aid project and would perform a cost-benefit analysis after its implementation. Therefore, there will be four sides to making a decision about international loans: a lender, a relevant ministry, the Ministry of Finance and the coordinator at the Ministry of Economy. Max Nefyodof explains that currently there is no one to access the risks such loans may entail, because no impartial party is involved in the decision process.

In fact, such a coordinator at the Ministry of economy formally existed until the beginning of 2016. However, in January, the government transferred the coordination of IFI projects to the Ministry of Finance. The Ministry of Economy is now responsible only for non-repayable aid. Tregub admits that the coordinator indeed underperformed.

Projects gathered dust on a shelf for years. Implementation reports were submitted in paper and lacked any kind of financial or technical details. They were all full of statements like “Everything went great, children smiled, schools shone”.

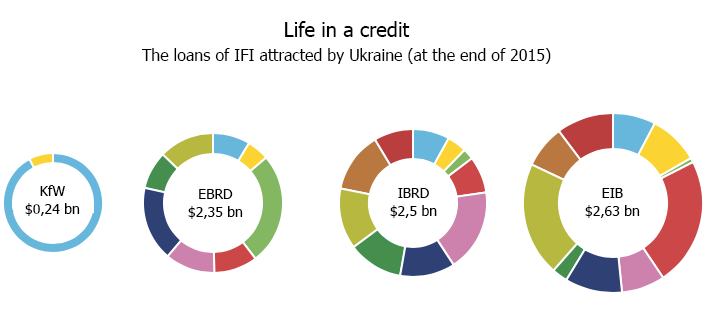

The World Bank, one of the largest lenders to Ukraine (Graph 2), also thinks that the coordinator did not function properly. However, the Word Bank opposes its re-establishment.

“They halted out projects for so many years! Why should the ministry interfere in the relations between creditors and borrowers at all? When there is no strategy of the country’s development, how can the Ministry of Economy know what, e.g., the Ministry of Energy needs?” wonders Maksimenko.

This opinion is shared by the former Deputy Minister of Finance Artem Sheveliov who only recently was in charge of loans from IFI.

High staff turnover and the confusion as to the division of responsibility for IFI projects has resulted in the low use of loans that the World Bank already agreed to issue to Ukraine.

On average, the countries of the region (27 countries in Europe and Central Asia) have used 12.5% of available loans in the ongoing financial year (since July 2015). Ukraine has used only 7%, says Maksimenko.

The country has to pay a fine for not using a reserved loan (on average $8 million annually in the last three years). According to Maksimenko, the Ministry of Regional Development is currently the least successful in implementing its projects.

On their own

While Ukrainian ministers and large donors are sorting things out, intermediaries and consultants in the area of donor aid are flocking to Ukraine. Anthony Sinclair, the development director of the US consulting company Cardno, has worked in the area of consulting in the financial sector of the Eastern Europe countries for more than 20 years. He has recently arrived in Kiev to learn more about a project that is being prepared in the financial sector and to liaise with top-officials that might be interested in it.

Consultants may play various roles in the process of implementing projects of donor aid and loans from IFI. In some cases, the intermediary company completely takes over the administration of a project, earning commission in return (the percentage can differ, as there is no single approach). Other consultants are involved in some parts of the project, e.g. drafting a law. Others simply consult government agencies, filling in their gaps in expertise, while the ministry’s employees are running the project itself.

If a project is administered by foreign consultants, they usually hire a local team of professionals, says Sinclair.

The deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine Vladyslav Rashkovan has nothing against the recommendations from professional consultants, but he is sceptical with regard to intermediaries between donors and recipients of aid. International assistance projects have to be initiated by their recipients (those who really need them) or, in some cases, donors or international financial institutions themselves, and not consultants. According to Rashkovan, the Ukrainian central bank is cooperating closely with more than a dozen of donors. Each is assisting in a different area of the Bank’s operations. “Why would we need additional intermediaries, if I know that there are only few specialists in a given sphere of central bank management in the whole world? We can find them on our own, we don’t need an intermediary to do that”, explains Rashkovan. In fact, the NBU has developed its in-house international assistance coordinator in the last 12-18 months. This department works with the Bank’s projects and liaises with donors.

Donor organizations do not oppose such an approach. “It would be much easier for us to do our job, if we knew what the strategy for the development of Ukraine is and what each government agency really needs”, says Danielsson of SIDA.

Despite yet another change of government, Tregub is not going to leave the Ministry. “I am not leaving until we launch the OpenAid portal and the law on the establishment of the national coordinator of international assistance is registered at the Parliament”, says Tregub. “I am in the process of explaining to the new leadership of the government why the new system of international assistance coordination is necessary. Despite the support we had from the Minister of Economy Abromavichus, the previous government rather blocked the reform”. According to Danielsson, ensuring the efficient coordination of donor aid and loans is a huge challenge to any developing country, including Ukraine. It is important to prevent the responsible agency from becoming a bottleneck, summarizes Danielsson.

VoxUkraine is grateful to its interns Iaroslav Kudlatsky, Maksym Skubenko, Andriy Kovakin, Lubov Balashov and Taras Kotov for their assistance in the preparation of the article.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations