Around two thousand draft laws are registered annually in Ukraine’s Parliament. During the Legislature’s 9th convocation (from December 2019 to March 2023), 5,293 bills were submitted for consideration versus 7,821 during its 8th convocation. This is significantly more than in other European countries. However, 50-60% of the registered draft laws receive negative comments from the Verkhovna Rada Chief Scientific and Expert Department (CSED). Approximately one-third receive negative comments from the Ministry of Finance, which may indicate an imperfect law-making process in Ukraine. Let’s examine this process and the main problems it contains.

Parliamentary reform

Parliamentary reform began eight years ago to improve the operation of the Ukrainian Parliament. On July 3, 2015, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine and the European Parliament signed the Memorandum of Understanding, defining the following priority areas: ensuring the effective performance of the constitutional functions of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (legislative, controlling, and representative); improving the quality of Ukraine’s parliamentary system; increasing the transparency, predictability, efficiency, and openness of the Verkhovna Rada’s work process. At the same time, the European Parliament’s Needs Assessment Mission prepared the report and road map on internal reform and capacity-building for Ukraine’s Parliament. It developed a list of recommendations for strengthening Parliament’s capacity. In March 2016, Parliament approved measures to implement these recommendations.

Parliamentary reform in Ukraine is less than halfway implemented. According to the Agency for Legislative Initiatives (Table 1), only 10% of the 52 Roadmap recommendations have been fully implemented, which is only 4% better than in March 2019. Overall, 45.7% of the reform was implemented as of July 2021.

Table 1. Status of implementation of the road map for parliamentary reform

| Completed | Partially completed |

| The implementation of the Information and communication technologies strategy | Legislative capacity and process in the Verkhovna Rada (25%) |

| The development and approval of the “digital” strategy | Political oversight of the Executive branch (50%) |

| The audit by the Accounting Chamber | Openness, transparency, and accountability to citizens (81%) |

| The implementation of the staff capacity-building strategy in the Verkhovna Rada | Approximation of the Ukrainian legislation to the EU acquis (50%) |

| Short-term internships in terms of employment conditions should be separated from internships for civil servants

|

Administrative capacities (61%) |

| Coalition, opposition, and dialogue within the Verkhovna Rada (19%) | |

| Ethics and conduct at the Verkhovna Rada (25%) |

Source: Assessment of Internal Reform Implementation and Institutional Capacity Building of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (as of July 2021), Agency for Legislative Initiatives, February 2022.

VoxUkraine monitors the legislative process in Parliament (see here and here). The course of parliamentary reform was also reviewed (see here and here).

Stages of the passage of the draft law and problems along the way

This article analyzes draft laws’ path to adoption, outlines some of the difficulties of the law-making process, and develops recommendations to improve Parliament’s quality of work and regulations in the future.

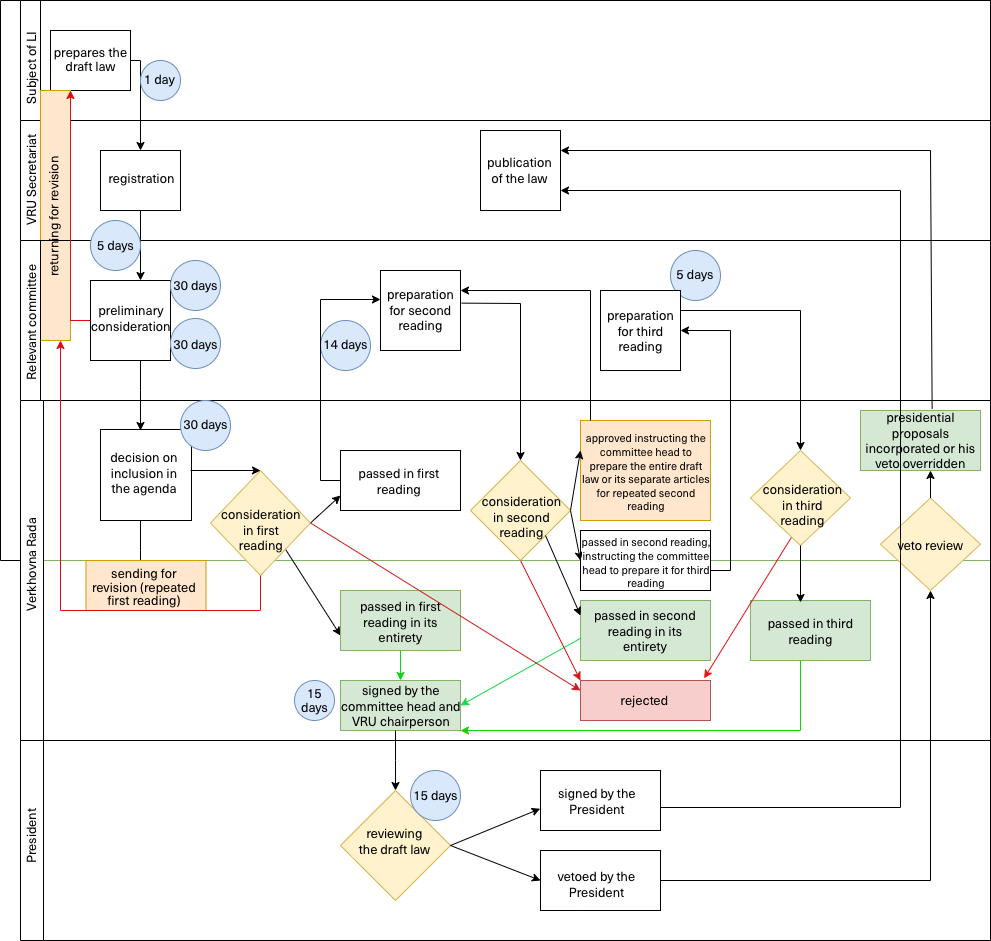

Each bill submitted to Parliament goes through several stages (Figure 1):

- registration,

- consideration at the relevant committee,

- vote/approval,

- signing by the President.

Each stage has its main “players” (see Table 2). Some specific problems negatively affect the passage and adoption process and the quality of the legislation under which the country later lives.

Table 2. Stages of the passage of the draft law

| Stages | Responsible |

| Preparation and registration | The subject of the legislative initiative: MP(s), CMU, President registration: the VRU Secretariat, chairperson |

| Consideration at the Relevant Committee

(preliminary review, first, second, and third reading, revision) |

The Relevant Committee; Committee on Budget; Committee on Anti-Corruption Policy; Committee on Ukraine’s Integration into the European Union; The Chief Scientific and Expert Department of the VRU (CSED); the Chief Legal Department of the VRU (CLD); the Cabinet of Ministers (state authorities); other interested persons |

| Inclusion in the agenda | Chairperson of the VRU, Conciliation Board |

| Consideration in Parliament | The majority of people’s deputies |

| Signing by the Chairperson of the Verkhovna Rada | Chairman of the Verkhovna Rada |

| The President’s decision | President, OPU |

Registration stage. Over 5,000 draft laws were registered in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine during the 9th convocation.

For comparison, 914 bills were registered in the UK in 2019-2023 and 1,802 in Poland. As for other countries, an average of five draft laws are initiated annually in Norway, 6 in Switzerland, 13 in Greece, 46 in Austria, 71 in Iceland, 74 in Denmark, 115 in Portugal, 227 in Belgium, 257 in Finland, 337 in France, 644 in Italy, and about 1.6 thousand in Ukraine.

50-60% of the bills registered in the Verkhovna Rada receive negative comments from the parliamentary Chief Scientific and Expert Department (CSED). Approximately one-third of draft proposals also receive negative feedback from the Ministry of Finance.

In Ukraine, bills can be submitted to Parliament by MPs, the President, and the Government. Until 2004, the National Bank also had this right, restored during the constitutional “reform” of 2010 and canceled again in 2020.

Today, MPs submit about 90% of draft proposals (only 686 out of 5,293 draft laws have been initiated by the Government during the 9th convocation). However, international practices show that 60-90% of the total number of bills are government-initiated in countries where the Government has the right to legislative initiative. The same percentage of governmental projects later become laws. In Ukraine, the President has signed only 13% of government-submitted bills considered during the 9th convocation. Overall, 16.8% of bills under the consideration of this convocation have become Laws vs. 12,3% during the 8th convocation and 9.7% during the 7th.

For comparison, 63.2% of government bills became laws in the Polish Sejm in 2012-2023 and 77.2% in the UK.

According to the Verkhovna Rada’s Rules of Procedure, a draft law will not be registered if submitted in violation of the requirements for the draft design and accompanying documents. Articles 90 and 91 of the Regulations list the technical requirements for registration and for the project itself, namely: the presence of supporting documents justifying the need for adoption; objectives, tasks, and main provisions; justification of the expected socio-economic, legal, and other consequences after the bill’s adoption; and availability of a comparative table, should changes be made to the current law. If changes to other statutes or by-laws are necessary to implement the provisions of the submitted bill after its adoption, such changes (or instructions to relevant bodies to make such changes) must be set out in the bill’s “Transitional Provisions” section or a separate bill introduced simultaneously by its initiator.

At this stage, the first problems arise. Poor-quality draft laws fail to meet the rules for drafting laws and basic legislative technique requirements and provide insufficient socio-economic and financial justification. They are poorly written, using terminology requiring further clarification, duplicating or contradicting the Constitution’s provisions or current legislation).

The problem is the number of registered draft laws, popularly called “legislative spam.” According to the Road Map, due to the excessive number of draft laws, the Verkhovna Rada Secretariat and MPs spend much time studying and discussing draft proposals. The excessive workload of processing a significant volume of draft laws leads to increased numbers of non-considered draft laws and reduced discussion time, even when reviewing necessary legislative acts. Therefore, the number of draft laws harms their quality.

According to the Rules of Procedure, VRU Secretariat employees do not analyze or ascertain whether the draft proposals duplicate existing or registered draft laws or contain proper financial and economic justification at the registration stage. All this is checked during the next preliminary review stage at the relevant committee.

Consideration at the relevant committee

After registration, the draft law goes to the relevant committee, where the main work is carried out, including preliminary consideration, analysis of relevance and social necessity, and quality. The committee examines the compliance of accompanying documents and the bill’s financial and economic validity and prepares and revises it for its first and subsequent readings. At this stage, other committees, executive power bodies, the Chief Scientific and Expert Department (CSED), the Chief Legal Department (CLD), and interested parties (employer associations, businesses, social groups, and trade unions) submit their conclusions and recommendations.

There are also problems at this stage:

- Poorly prepared accompanying documents and lack of financial and economic justification prevent the relevant committee (DC) from making a decision. In this case, the committee can return the bill for revision. A practical solution to this problem could be training the MPs and their assistants or creating an office of the parliamentary counsel. Such Offices have proven their practical effectiveness in parliaments abroad.

- Significant differences in various stakeholders’ viewpoints delay a compromise. In such cases, the committee can create a working group to finalize the draft law. However, sometimes working groups do not work toward reaching a compromise delaying the adoption of the decision regarding the bill in question. For example, the creation of a working group practically blocked the consideration of the draft law on labor #2708 since trade unions and employers could not find a compromise on some provisions;

- The draft law is amending a large number of various laws. Such bills are designed to comprehensively resolve a problem. On the other hand, analyzing and finalizing them is difficult, and such projects “are shelved” under the committee’s consideration for a long time. For example, draft law No. 3515 on changes in the methods of calculating the living wage was adopted in first reading on June 2, 2021, but its preparation for second reading is still underway. This project proposes to amend 46 pieces of legislation, changing the definition of the living wage and reviewing the payment amounts, including the minimum wage and salaries of public sector employees. It is also proposed to introduce the concept of a unit of account in the law on the state budget to set fines and penalties for committing offenses; settle the issue of administrative services fees; change approaches in forming the minimum amounts of various types of social assistance and pensions, etc. For such complex reforms, it makes more sense to “eat the elephant piecemeal” to develop a road map and review and adopt changes in individual bills.

Upon consideration, the relevant committee can either recommend including the draft law in the session’s agenda or return it to the subject of the legislative initiative for revision. Reasons for returning bills for modification include the following:

- the Committee on Legal Policy’s conclusion that the draft law contradicts the provisions of Ukraine’s Constitution;

- the Regulation Committee’s conclusion that the introduced draft law was drawn up and/or registered not in line with the Rules and Regulation and related legal norms;

- lack of financial and economic justification if the relevant committee does not think it possible to consider it without such justification;

- the presence of a draft law adopted in first reading, to which the draft proposal is an alternative;

- rejecting a draft law for the current Verkhovna Rada session, whose provisions literally or essentially repeat the submitted draft law

Figure 1. The path of the draft law

Source: compiled by the author according to the VRU Rules of Procedure

When the Verkhovna Rada reviews the draft law in first reading, it is typically returned to the committee for revision before second reading. However, there may be other decisions: adoption in entirety, rejection, or re-sending for first reading (in the latter case, the draft law may be published for public discussion).

When considering the draft project before second reading, other problems arise, mainly the excessive number of amendments for second reading submitted by MPs. This delays the process of preparing the draft law for second reading by the relevant committee and its consideration in Parliament. For example, more than 16 thousand amendments were submitted to block the so-called “anti-Kolomoisky” bill. Over 4 thousand amendments were sent with regard to the project on the circulation of agricultural land, 2332 amendments regarding the bill on media, and 1197 comments to amend the bill on the use of the 2022 state road fund.

For the purpose of eliminating this problem, precisely after reviewing the “anti-Kolomoisky” bill in April 2020, changes were introduced to the VRU Rules of Procedure regarding restrictions on submitting and reviewing amendments for second reading. Namely, if the number of revisions is at least 500 and 5 or more times the number of draft law articles, the Verkhovna Rada may decide in favor of a special procedure. After such a decision, each faction (deputy group) has the right to send to the relevant committee no more than five proposals (no more than one proposal for non-factional MPs) on which they insist. Applying this procedure will reduce the time for second reading of the bill in the session hall. However, the relevant committee will still spend time preparing and entering all amendments and proposals in the comparative table of the draft law suitable for second reading.

Usually, draft laws are either adopted in their entirety or rejected during second reading. However, Parliament can also return draft laws or their particular articles to second or third reading. If the bill is not abandoned after third reading, it is passed and sent to the President for their signature and, in some cases, to an all-Ukrainian referendum. However, the postponement of a final decision is not excluded for various reasons.

When considering and voting on the draft law in the session hall, amendments are sometimes made to it “by voice,” which are difficult to track without seeing the transcripts or videos of the plenary sessions. For example, when reviewing draft No. 8008, amendments to its second reading were voted on “by voice” in the session hall (the bill aimed to reduce the term of remaining in the status of a public person from life to three years). However, the relevant committee did not support these amendments as the bill itself pursued a different goal of protecting Ukraine’s financial system from Russia.

Other problems on the path from bill to law

In addition to the problems mentioned above, other factors cannot be attributed to a specific stage but significantly affect the process of reviewing and adopting laws.

The Conciliation Board’s decisions (regarding inclusion or non-inclusion of draft laws in Parliament’s agenda, see Table 2). The Conciliation Board comprises representatives of all factions and groups (see the box). Therefore, theoretically, decisions regarding which draft laws to consider quickly and which to postpone by putting them “in a long drawer” are made collegially in Parliament. However, in current conditions, such decisions are taken by the mono-majority.

Composition of the Conciliation Board of the VRU

According to the Verkhovna Rada’s Rules of Procedure, the Conciliation Board consists of the VRU Chairperson, the First Deputy, the Deputy Chairperson of the VRU, MP faction heads (chairs of deputy groups) having the decisive vote, and heads of committees in an advisory capacity. In case of absence, their deputies participate in board meetings. Representatives of parliamentary factions and groups vote on the decisions of the Conciliation Board. However, their vote’s “weight” equals the number of MPs of the respective faction or group. Decisions are considered adopted if they receive the voices of those factions that provide a total of at least 226. Under current conditions, the Servant of the People faction can approve the agenda independently.

Table 2. Estimated duration of reviewing draft laws

| Stages | Days | ||

| Registration | 1 | ||

| Submission to the relevant committee (DC) and other committees | 5 | ||

| Preliminary consideration at the DC | 30 | ||

| Preparation by the DC for first reading | 30 | ||

| The Verkhovna Rada’s decision regarding inclusion in the agenda | 30 | ||

| Review in first reading | ?* | ||

| Taken as a basis in the entirety | 96 | ||

| Preparation by the DC for second reading | 14 | ||

| Review in second reading | ?* | ||

| Passing in second reading and in the entirety | 110 | ||

| Preparation for third reading | 5 | ||

| Review in third reading | ?* | ||

| Passing in third reading and in the entirety | 115 | ||

| Signing by the relevant committee | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Signing by the VRU chairperson | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Signing by the President | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Law | 126 | 140 | 145 |

Source: compiled by the author according to the VRU Rules of Procedure

*The Conciliation Board determines when the draft law will be brought to the session hall for voting on (I, II, III readings). The timeframe for when exactly this is due is not defined.

The role of the opposition (parliamentary minority). Clearly, the parliamentary majority’s representatives have better chances of getting their bill passed. In the Ukrainian Parliament, all MPs have equal rights. Still, there has long been discussion of the legislative consolidation of certain rights available to the opposition (by their very nature, oppositional activities are not regulated by separate laws in the vast majority of countries). However, in 2008-2009, the 2008 VRU Rules of Procedure) governed the status of the opposition by granting it certain rights and opportunities. These changes to the Rules of Procedure were introduced by the Party of Regions when it was in opposition and were later canceled after the party came to power and decided to limit the opposition’s rights.

Rights of the opposition according to the 2008-2009 Rules of Procedure:

- The agenda of the plenary sessions of the Verkhovna Rada for each day of the plenary week was prepared to take into account the proposals of the parliamentary opposition;

- The parliamentary opposition during the plenary sessions of the Verkhovna Rada had a guaranteed right to a 5-minute speech by its representative when Parliament considered the following issues: 1) principles of Ukraine’s domestic and foreign policy; 2) the CMU action program; 3) the status of implementation of Ukraine’s State Budget; 4) the responsibility of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine; 5) the national program of economic, scientific, technical, social, national, and cultural development, and environmental protection.

- The opposition could create an opposition government consisting of MPs (parliamentary opposition members). Members of the opposition government had the right to:

- receive information and copies of acts adopted by the Cabinet of Ministers;

- monitor the activities of the CMU and other executive bodies and their officials;

- exercise control over the development and implementation of Ukraine’s State Budget within the limits of parliamentary oversight;

- prepare alternative proposals regarding the CMU programs and acts and publish them in the parliamentary mass media and on the Verkhovna Rada’s official website;

- develop legislative proposals alternative to those submitted by the Cabinet of Ministers;

- develop alternative national program projects.

When distributing the positions of committee chairpersons, first deputies, deputy chairpersons, secretaries, and members, the parliamentary opposition was given the primary right to opt for the following positions: 1) chairpersons of committees on budget, regulations, freedom of speech and information, rights of national minorities and international relations, freedom of conscience, social policy, health care, science and education, judiciary, judicial system, legislative support of law enforcement activities, fight against organized crime and corruption, activities of state monopolies, national joint-stock companies, and management of state corporate rights; 2) first deputy chairpersons in committees, the positions of chairs in which belong to the coalition quota in line with the principle of proportional representation of deputy factions in committees.

The only substantial provision of the 2008 Rules of Procedure was distributing positions in parliamentary committees since oversight over the Government’s activities and the development of legislative proposals is the right of any parliamentarian, not only the opposition.

The unsettled issue of citizens’ participation in the law-making process. At the beginning of his term, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky registered a draft law to amend Article 93 of the Ukrainian Constitution (regarding the people’s legislative initiative). Still, Parliament never got around to considering it. Currently, the public can participate in discussing bills published on the website of the VRU and the CMU (i.e., websites of the Ministries designing draft laws, such as the Ministry of Economy). Citizens also have the right to submit petitions to the President of Ukraine regarding problematic issues that need to be resolved at the level of the President, the CMU, or the Verkhovna Rada.

In Ukraine, there are also specific problems relating to the legislative process, e.g., “poor-quality” bills (submitted without proper justification or contradicting the current Constitution or laws). As a result, Parliament spends a lot of time reviewing “raw” bills with little chance of passage because the “filter” for bills submitted by the people’s deputies is the weakest. Draft laws proposed by the CMU must be agreed upon with all authorities involved and undergo public consultation, while PMs’ drafts are registered “as is.” It is no secret that sometimes this is also used by executive powers to “circumvent” the law-making procedures of the CMU.

How can the legislative process be enhanced?

In short, the recommendations (including those in EU Parliament’s Road Map) boil down to (1) giving fuller consideration of the interests of various parties and (2) paying greater attention to draft laws’ technical side (availability of accompanying documents and its compliance with current legislation). More details are given below.

The Road Map (RM) proposes adopting an ‘end-to-end’ legislative process based on greatly enhanced coordination between the originators of legislative proposals. For example, MPs must consult with the Government before submitting draft laws because, say, the Ministry of Finance might have significant comments regarding the draft proposal, or it may happen that another ministry is already working on a similar idea.

In addition, the RM suggests that prior to the deposition by the Government of substantial pieces of legislation to the VRU, a discussion’ white paper’ (explaining the policy objectives of the proposed legislation and the broad measures to be introduced). In this way, the committee can start discussing relevant ideas before introducing the bill.

This recommendation could be extended to MPs as well. In addition, it would be possible to provide for a minimum number of draft law authors in the Rules of Procedure. This will force the drafters to dialogue with each other and discuss ideas (“rules of the game”) that will benefit society as a whole. Such an agreement would also increase the chances of the bills’ passage. Such restrictions apply in some countries, particularly in Spain and Poland, where draft laws can be introduced by an entire faction or at least 15 deputies. Latvia requires the signatures of 5 people’s representatives, Germany at least 5% of the Bundestag, or that it be an initiative from a faction. In Estonia, Slovakia, and Hungary, only committees can submit bills. By the way, although the percentage of draft laws prepared by committees (marked with the letter “f” meaning “finalized” next to the number of the draft law) is low in the VRU, amounting to 1.3% of registered bills, the percentage of their adoption is high (54.3%).

It would also help to increase the role of experts and interested groups in reviewing draft laws. These groups could provide legislators with valuable information and expertise, helping them make informed decisions. Most VRU committees engage a wide range of experts and representatives of business and public groups when reviewing bills. Still, their comments and conclusions are not always taken into consideration. Yet, since the committee determines who to include in the discussion, there is a risk of ignoring “undesired” voices. Moreover, draft laws are often passed regardless of the negative comments from the Chief Scientific and Expert Department or the Chief Legal Department.

Possible solutions to this problem:

- obliging CSED and CLD to submit proposals to draft laws to correct the identified shortcomings (e.g., those contradicting current legislation);

- establishing in the Rules of Procedure that in the case of negative comments from CSED and CLD during consideration by Parliament, draft laws are automatically returned to the relevant committee for revision;

- creating an office of the parliamentary counsel to draft laws or provide recommendations during their preparation;

- creating Expert Committees or Councils to assess the quality of draft laws by analogy with foreign structures. By the way, in October 2022, the Research Service of the Verkhovna Rada was established in Ukraine, providing scientific research, information, and analytical support for the activities of the Verkhovna Rada, its bodies, Ukrainian MPs, and parliamentary factions (deputy groups). The Research Service also conducts professional training (advanced training) of MPs, VRU Secretariat employees, and assistant consultants to Ukrainian MPs. It would be appropriate to authorize the Research Service to prepare draft laws for registering, e.g., as requested by a committee or the VRU chairperson.

The European Parliament’s recommendations include a proposal to oblige the VRU Secretariat to conduct a thorough analysis of each piece of proposed legislation to ensure it is not a duplication of (or in contradiction with) the body of national legislation.

In addition, the parliamentary opposition’s rights must be considered. In particular, the European Parliament’s recommendations, like many pre-election promises, include adopting the law on the opposition (in particular, recommendation 44 stipulates that an early decision should be made and implemented to regulate the status of the parliamentary opposition). In any case, some rights of the opposition laid out in the 2008-2009 VRU Regulation of Procedure are worthy of attention, in particular, taking into account the opposition’s proposals when forming the agenda or giving priority rights to the opposition factions when electing of some parliamentary committees’ leadership.

For example, in Germany, there is the tradition that the positions of the chairperson of the budget committee and the petitions committee are held by representatives of the opposition. Also, the opposition mainly forms the Bundestag’s scientific, expert, and auxiliary services.

The Italian Chamber of Deputies has a special regulatory committee, equally represented by the majority and the opposition, with a task to evaluate the quality of draft laws’ texts for integrity, simplicity, comprehensibility, and compliance with their objectives, as well as effectiveness in the context of simplifying and reorganizing the current legislation. Based on these parameters, the committee prepares and submits reports regarding draft laws to other committees.

And finally, increasing the transparency of the Verkhovna Rada’s work. During martial law, information on the website of the VRU is partly closed, and there are no live broadcasts of the MPs’ work in the session hall. People’s deputies attempted to resume coverage of the VRU’s activities (see here and here), but the corresponding draft resolutions were not passed. Moreover, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine adopted bill No. 9005 in first reading, prohibiting the dissemination of information about Parliament’s plenary sessions. Accordingly, the public cannot immediately see the representatives of the mono-majority (in the absence of deputies in the session hall and the insufficient number of votes to make a decision) voting together with the representatives of the former Opposition Platform For Life faction. Overall, the lack of transparency in considering decisions negatively affects the quality of the law-making process.

If it is impossible to resume live broadcasts of the parliamentary meetings, their recordings should at least be published with a slight delay. It is entirely inappropriate to prohibit MPs from reporting socially important information about the course of plenary sessions. After all, people’s deputies are representatives of society and should be primarily accountable to their voters.

Conclusions

The biggest problems of the law-making process in Ukraine are the poor-quality preparation of draft laws and their large number. The committees spend much time determining the need for changes and finalizing the submitted projects. In turn, Parliament does not have time to review all draft laws properly, which results in passing laws that contradict Ukraine’s Constitution or current legislation.

In order to improve the law-making process, the main work on draft laws should be shifted to the development stage (before registering them in the Verkhovna Rada) and not to the consideration stage at the relevant committee, as is currently the case. Thus, it is necessary to strengthen the VRU’s advisory and expert bodies. In addition, work on draft laws should be carried out openly by involving public discussion and transparently by ensuring wide media coverage.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations