Russia continues to discredit Ukrainian soldiers. Recently, this campaign has not intensified as much as it has transformed: in addition to an increase in the number of Russian fabrications, photofakes, and deepfakes have been added. We explain the latest trends, how the Ukrainian military is being discredited, and how to recognize falsifications.

Such attention to the Ukrainian military from Russian propaganda is not surprising — according to polls, the army enjoys strong public trust. Russians have been trying to discredit the Ukrainian army in various ways since 2014. Their number has increased with the start of the full-scale invasion, and their tactics constantly change.

Various examples of Russian fabrications can be found online: poorly staged scenes, bad photo editing, fake reports, and websites that pretend to be Western media outlets. In parallel, Russian propaganda is mastering artificial intelligence and faking news that portrays soldiers as the main culprits in any given situation. These fakes are still imperfect, but sometimes of higher quality.

Let’s review the recent Russian fakes and how to counter them.

Masterpieces of Russian cinema

Russian propaganda regularly creates staged videos. For example, Russians published a video in which a supposedly mobilized man beats a Territorial Recruitment Center officer, who was also sent to the front. Or they claim that a soldier allegedly beat a policeman in Kharkiv.

Staged videos

For some videos, Russians use the same “actors”. For example, they published a video where supposed Territorial Recruitment Center soldiers lower a woman into a well. The reason for such “punishment” was allegedly her attack on a soldier supposedly, she was protecting her husband. After some time, another video appeared in which “Ukrainian soldiers” execute a woman. According to the “plot”, she sold low-quality alcohol to the Ukrainian Armed Forces, which led to their deaths. The women in both videos are similar: they have the same voice and similar clothing.

Staged videos with the same “actress”

How to recognize a staged video?

- “Phenomenal” acting (sometimes by the same actors).

- Their accent often gives them away. Although Russians improve their Ukrainian, it’s far from perfect.

- Inappropriate clothing, with incorrect or missing identification signs.

- Key details, such as addresses, names, dates, etc., are missing, which is strange since the videos are supposedly made for wide distribution.

- Dubious sources distribute the videos. Russians use phrases like “received the video from the phone of a captured/killed Ukrainian soldier” or “found it on Ukrainian TikTok”. For the latter, Russians create the accounts themselves.

- Strange filming angles prevent the most important details (faces or shooting moments) from being shown during the shoot.

Photo editing and Russian disinformation

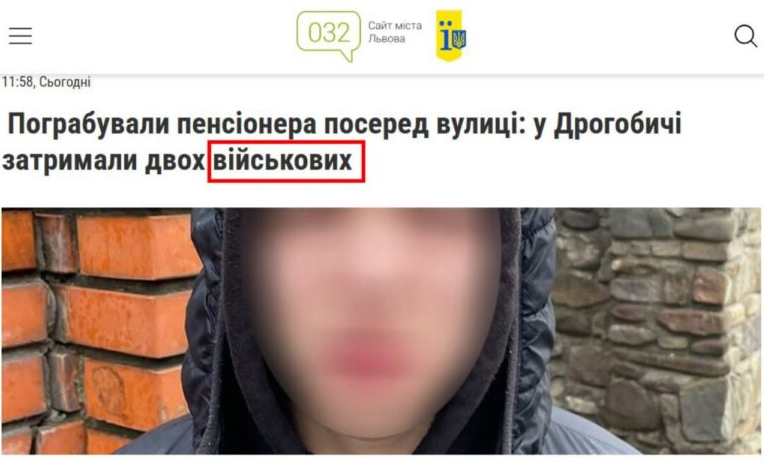

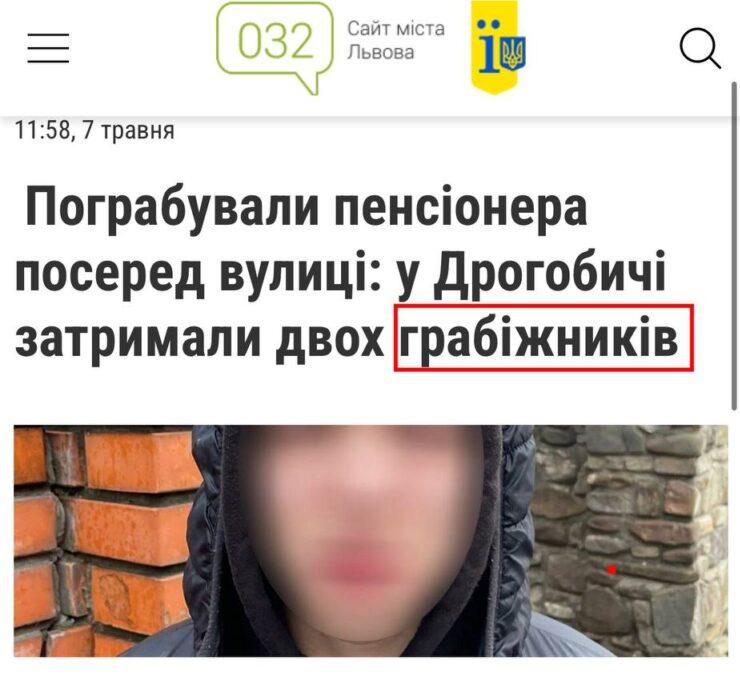

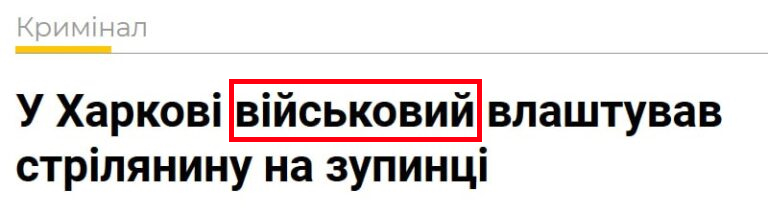

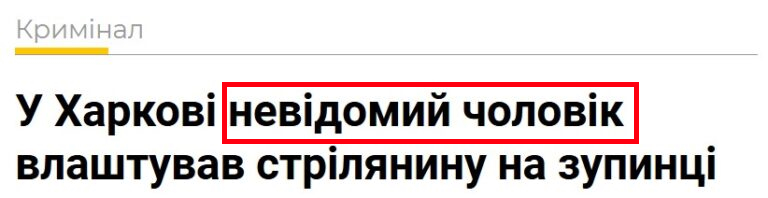

In addition to video staging, Russian propaganda also spreads edited screenshots, attributing looting, murder, or other crimes to Ukrainian defenders. To create them, text about soldiers is inserted into real articles about crimes in Ukrainian media. However, in the original version, there is no mention of the military being involved.

Top — fake news. Bottom — original article

Top — fake news. Bottom — original article

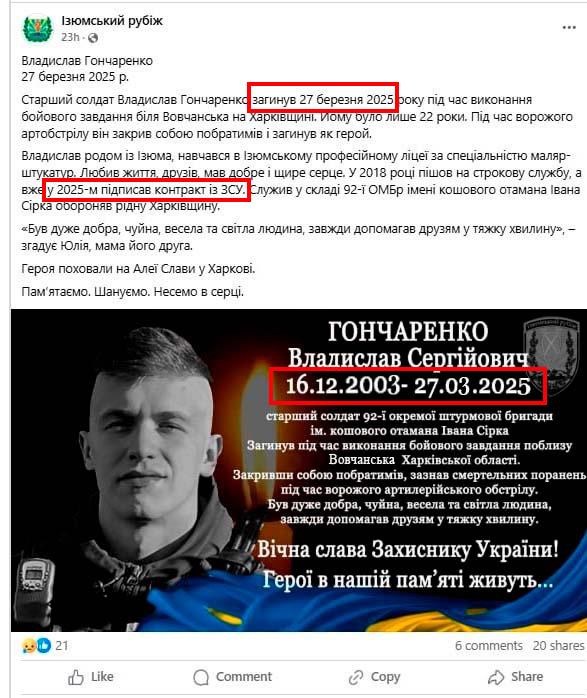

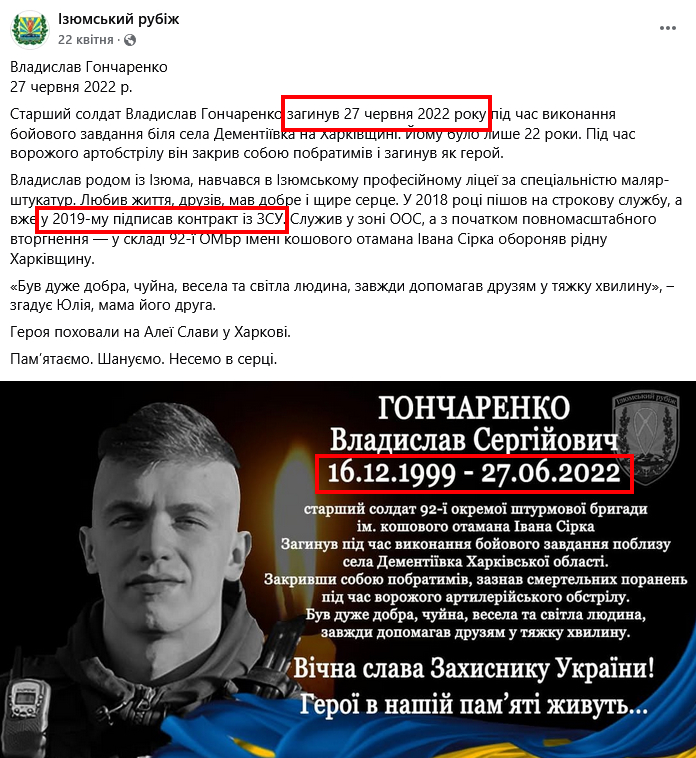

A separate line of photo fakes involves edited obituaries. Russians especially focus on discrediting the “18-24 Contract”. They falsely claim that soldiers who signed the contract died before finishing their training.

Russians spread similar fakes about the deaths of Oleksandr Samoylovych and Vladyslav Honcharenko, who allegedly agreed to the “18-24 Contract”. These soldiers, unfortunately, did die, but had no relation to the program. Posts about their deaths were edited.

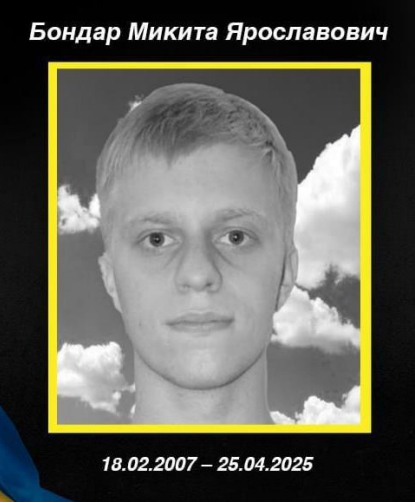

Another example: propagandists invented the name of an 18-year-old soldier (Mykyta Bondar) and used the photo of an Olympiad-winning computer science student to create a fake obituary.

With the help of the facial recognition service PimEyes, we established that the person in the photo is not Mykyta Bondar, but Denys Tereshchenko. The boy has repeatedly participated in informatics olympiads. The photo used for the fake news about the death was taken in September 2024. At that time, the boy won a silver medal at the International Olympiad in Informatics in Alexandria, Egypt. In September 2024, Tereshchenko was in 11th grade, so his studies were supposed to continue until May 2025. That is, he could not have joined the army, as he was still in school.

How to recognize photofakes?

- Find and review original publications about the event (news in media or a social media post).

- Additionally, the information must be verified in reliable national or regional media.

- Perform a reverse image search to find the original photo and information about it.

Artificial intelligence in the service of Russian propaganda

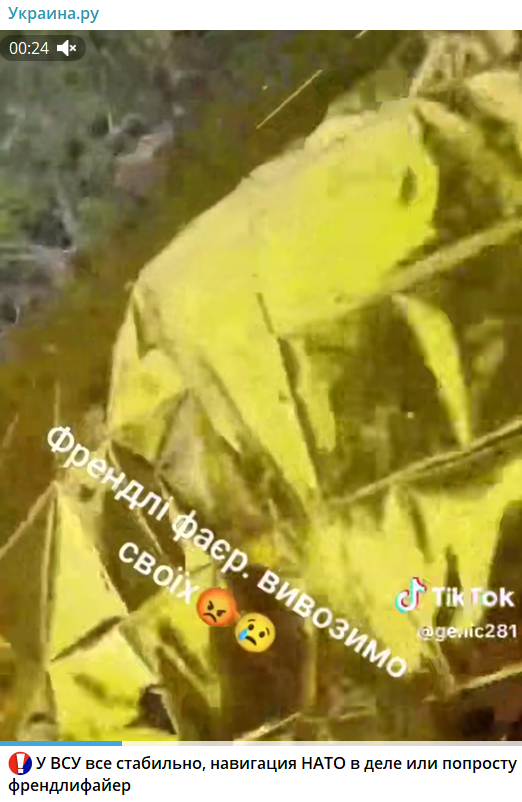

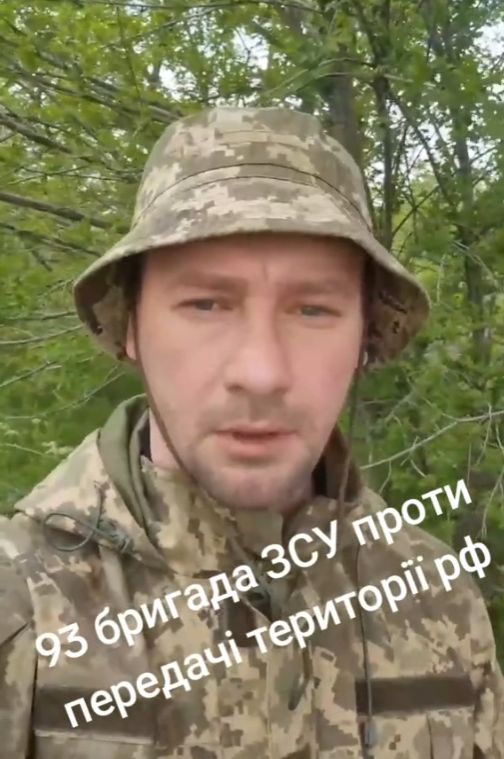

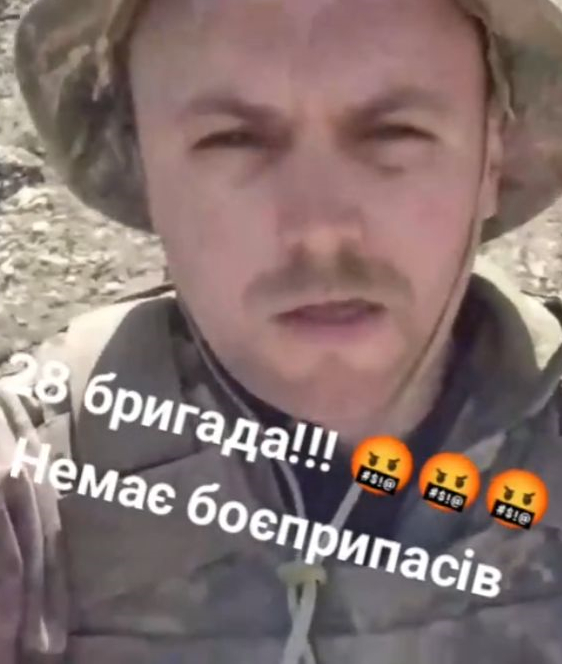

Russian propaganda also uses artificial intelligence to create fake videos or photos. For example, Russians spread a video in which a supposed Ukrainian soldier talked about “friendly fire” due to a lack of coordination between troops. Or a soldier allegedly speaks about unauthorized absence from a military unit due to losses and poor leadership. To create them, Russians replaced faces and generated audio tracks.

Fakes created using artificial intelligence

There are also examples where the same “soldier” serves in different units and has a different voice.

Video created with AI

With AI, not only fake videos about soldiers but also photos are created. AI-generated images have repeatedly appeared online, calling to pray for soldiers or congratulate them on a holiday. However, not all AI-generated content is so “harmless” — later, such posts may exploit public trust in the military and spread “betrayal” narratives.

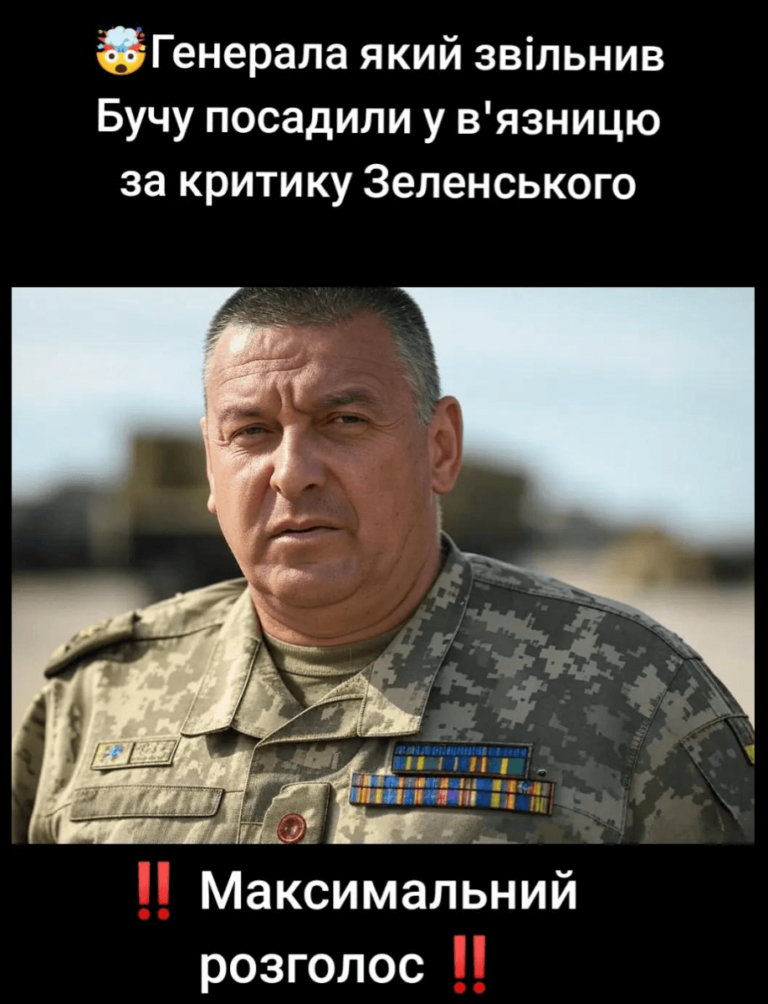

For example, a photo was spread online of a supposed general who “liberated Bucha” and was later imprisoned for criticizing Volodymyr Zelenskyi. In fact, the image of the soldier was generated using AI.

AI-generated photo

How to recognize deepfakes?

- Discrepancies in gestures: the face looks unnatural, head movements are harsh, and facial expressions don’t match the words.

- Visual defects include “glossy” skin, extra fingers, a blurred background, or elements that look strange and out of context.

- “Perfection of the photo”: the image looks studio-lit and perfectly symmetrical, with ideal poses and camera angles. The skin has an unrealistically smooth and clear texture, lacking human imperfections.

- Inaccuracies in clothing, insignia, etc.

- Illogical arrangement of objects (e.g., the same building looks different in two related images), unrealistic lighting, or violations of laws of physics.

- Audio inaccuracies or errors (absence of background sounds, unnatural sounds, or inconsistencies).

- Low-quality sources are spreading the fake (common for many fakes).

- You can use tools to detect AI (Hive Moderation, Deepware Scanner, or DeepFake-o-meter). While they don’t give a 100% result, they help detect fakes when combined with other methods.

Russian propaganda relentlessly refines its methods of discrediting Ukrainian soldiers, combining old tools like staged videos and photo editing with modern technologies, including artificial intelligence. From crude fabrications to deepfakes, each tool aims to undermine trust in the Defense Forces, which remain a key pillar of society. However, numerous signs of falsification — from acting mistakes to AI technical flaws — allow us to expose these fakes. If you notice suspicious information online, use our verification tips.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations