The simmering military conflict in Donbas and the Russian mass propaganda campaign are widely seen as boosting Ukrainian national identity. One recent analysis summarizes the popular opinion: “In the context of the war, Ukrainians are becoming only more united in their patriotism and opposition to Russia.” The growing Ukrainian nationalism that transcends the ethno-linguistic divides and long-standing political animosities is an appealing ideal, but our research suggest it might not be the case in all parts of the country.

The simmering military conflict in Donbas and the Russian mass propaganda campaign are widely seen as boosting Ukrainian national identity. One recent analysis summarizes the popular opinion: “In the context of the war, Ukrainians are becoming only more united in their patriotism and opposition to Russia.” The growing Ukrainian nationalism that transcends the ethno-linguistic divides and long-standing political animosities is an appealing ideal, but our research suggest it might not be the case in all parts of the country.

In a recent study we analyzed virtual communication carried out by Ukrainians via VKontakte (VK.com)—the largest, by the number of registered users and daily visits, social media platform in Ukraine. We were interested to see whether the war in Donbas affects online communication. It should be noted that following the 2014 resignation of VKontakte founder Pavel Durov over the issue of collaboration with the Russian government, many anti-Russian users left VKontakte in protest. Such ideologically motivated self-selection made the remaining VK audience somewhat more uniform (skewed in Russia’s favor), making us less likely to find political segregation. Another factor that might bias the results is the fact that our data includes occupied Southern and Eastern provinces, where pro-Ukrainian residents might be afraid to voice their opinion in fear of repressions.

Scholars have long recognized war as a companion and catalyst of nation building. External threats may heighten the sense of in-group unity, reduce internal divisions, suppress dissent, and help unify the nation. When studying Ukraine, however, it is unclear whether the war in Donbas would have such a unifying effect. Ukraine has long being divided along the overlapping regional, ethno-linguistic and political dimensions. Does Ukraine’s war over its territorial integrity and freedom to make political choices promote the unity among its people? Or does the war further exacerbate the existing divisions, which may fragment and polarize the society and hinder the development of an inclusive civic nationalism?

In order to address these questions we collected original data on the cross-regional structure of politically relevant online communication. Using the keyword search for political content we identified 14,777 public communities (discussion groups), 19,430,445 wall posts and 62,193,711 comments supplied by VK users residing in Ukraine. Utilizing the date and time stamp, as well as user-reported place of residence we constructed a panel of province-level daily observations measuring volumes of online communication, as well as its inter-regional fragmentation and polarization. We supplemented our online networks data with data tracing province-specific war casualties obtained from online sources, as well as the aggregate socio-economic statistics.

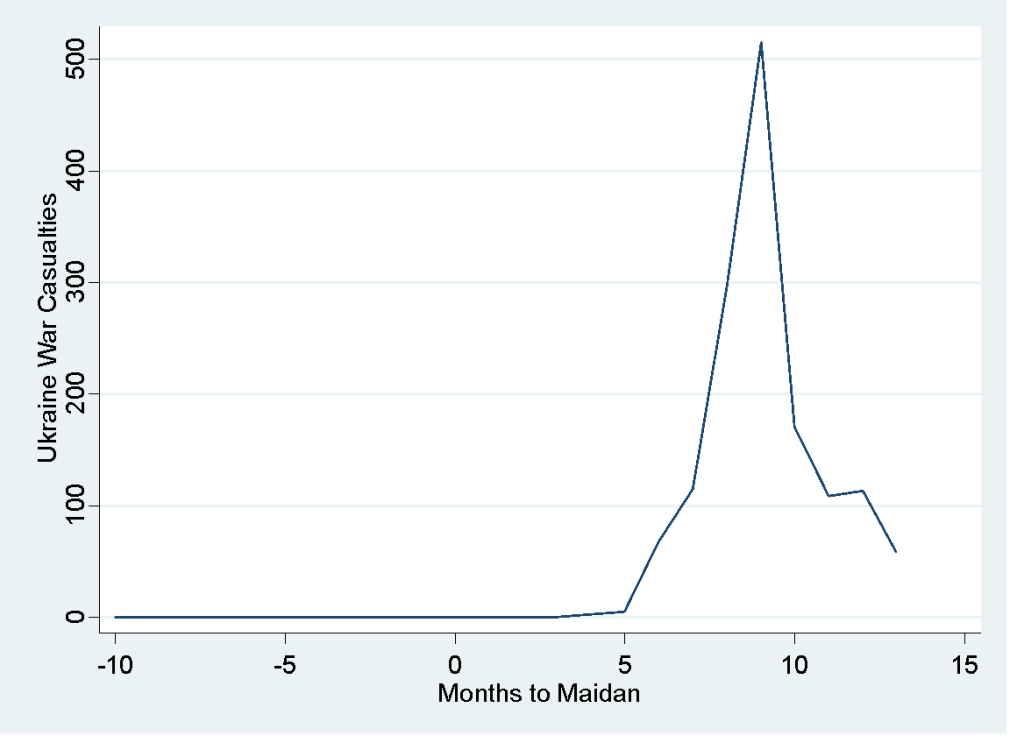

War casualties were first reported in March 2014, and peaked in August at over 500 dead.

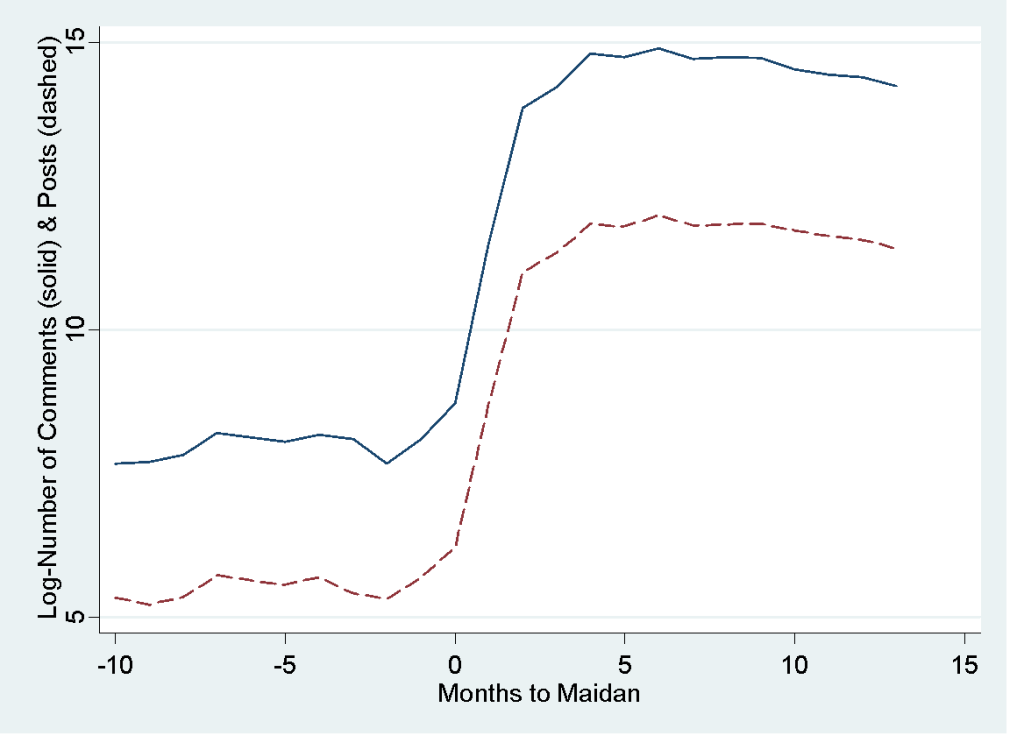

Coincidentally, we can clearly see the exponential rise in the user activity following Maidan protests in November 2013 and the start of the conflict. In fact, the average number of comments to political posts grew from roughly thousand per months in early 2013 to several millions in 2014.

Using a fixed effect time series statistical models we found that reported casualties heighten the online activity as measured by the number of comments. This effect appears to last for at least a week and is robust to restricting the sample to post-Maidan period.

While the news about war casualties heighten online activism across the entire country, regional analysis suggest that in West-Central provinces users show more solidarity with causalities from other provinces, while the online activism of their East-Southern counterparts is driven primarily by their home province losses.

These findings agree with a recent experimental study by Michal Bauer, Alessandra Cassar, Julie Chytilová, and Joseph Henrich who find that war experiences strengthen individual preferences for in-group parochialism, but reduce trust in strangers. The information about the province-specific war casualties may activate regional identities, heighten the sense of belonging to a narrowly defined group, and alienate the out-group members.

Nevertheless, our results are in part reassuring: not only war casualties activate online participation; at least in some parts of the country Ukrainians are sensitive to casualties suffered by other provinces. But does the Ukrainian online public become more united in response to the violent conflict in Donbass? Do people from different provinces communicate more across regional lines? We identify two dimensions of cross-regional communication: levels of cross-regional fragmentation, defined as the lack of connections (exchange of information) between different groups in the society, and the degree of its polarization, or difference in the intensity of positive and negative sentiment. If Ukrainians are becoming more united in the face of the war one would expect to see decreasing fragmentation (segregation) and polarization of network communication.

To study fragmentation, we analyze VK discussion boards, in particular the regional distributions of users leaving comments under wall posts. To assess how fragmented each discussion is, we use the following logic. For any pair of regions, fragmentation is high when the majority of comments in a discussion primarily come from only one of the two regions. On the other hand, fragmentation is low when both regions are equally represented in a discussion, indicating that the conversation is inclusive and an inter-regional exchange of opinion is taking place. Thus, we define a cohesion index (a reverse of fragmentation) that equals zero when only one particular region is represented in the comments, and the index achieves the maximum of one when both regions are equally represented, each contributing 50 percent of comments to a discussion.

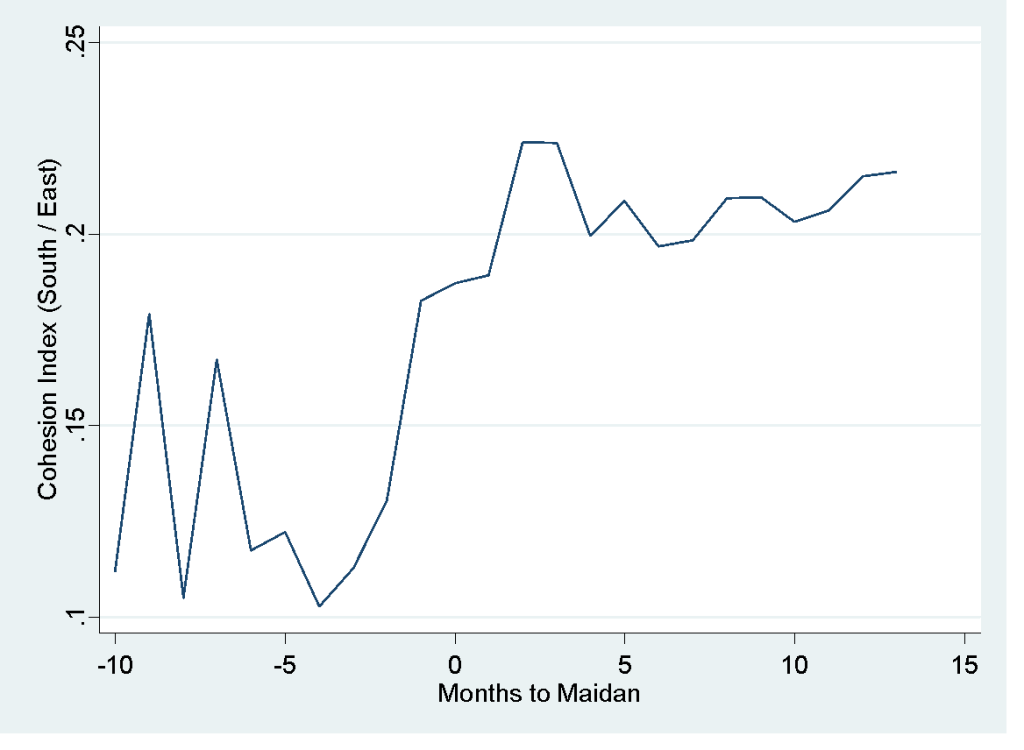

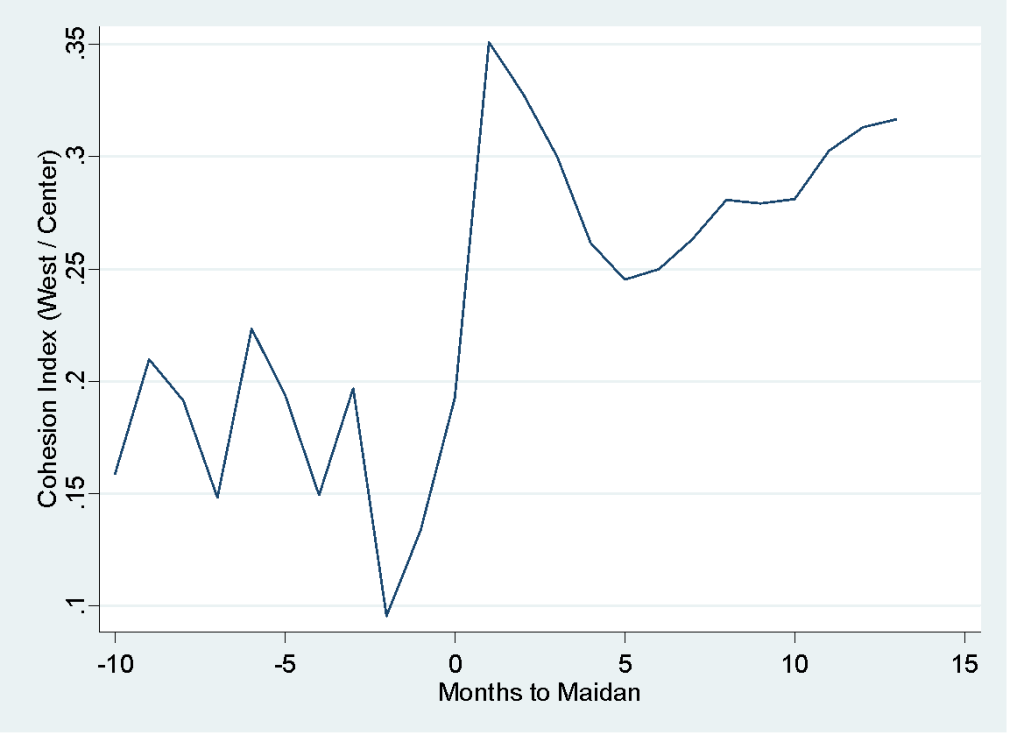

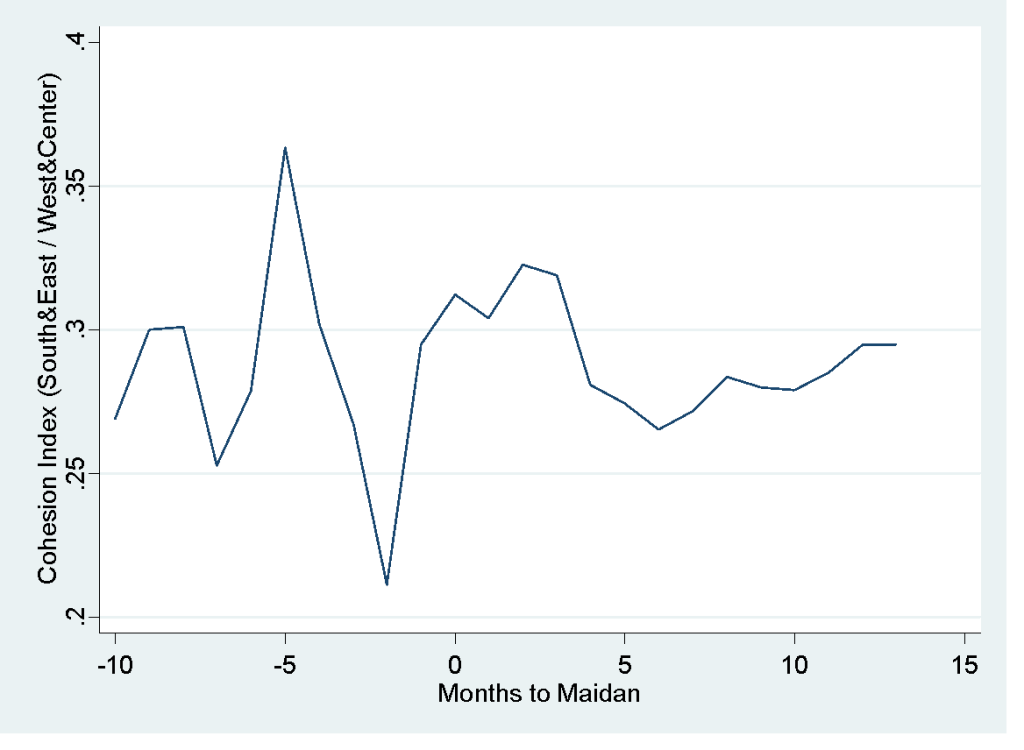

The three figures below illustrate how our dyadic cohesion index, measuring fragmentation of communication between two different parts of the country, evolved over time in 2013 and 2014. If we look at what is typically thought as two homogenous regions of Ukraine—East-Southern and West-Central provinces,– we can see that discussions within these two groups of provinces became much more integrated and inclusive after Maidan.

Indeed, while we see several temporary spikes in communication cohesion in the early 2013, the average value of the index was around 0.15-0.20 before Maidan. The index showed a clear upward trend and reached 0.20-0.35 in 2014. The difference is statistically significant.

Things look very different, however, if we consider communication between provinces located in Southeast Ukraine and the Westcentral part of the country. As before, we can see that before Maidan, most internet discussions were one-sided and conducted by representatives of the same region. This result is in line with the recent study by Dinissa Duvanova, Alexander Semenov and Alexander Nikolaev who find that most communication typically happen within rather than between Western and Eastern parts of the country. Surprisingly, this remained to be the case even after the start of the war – as can be seen from the graph, there is no clear break in the dynamics of the index.

Hence, we found no evidence that war casualties impact the level of network cohesion and bridge together broad East and West of Ukraine: Even though fragmentation does decrease, it is happening separately for each of those two regions, thus having no effect on inter-regional online communication. While the intensity of military conflict entices online activism, it activates regional rather than nation-wide connections. Our analysis suggests that at least in the sphere of social network communication the war does not unite Ukrainians that use VK and, who are living far apart.

One caveat to our analysis is that communication does not mean an agreement. In order to differentiate between constructive and destructive conversations, we analyze their content with the help of positive and negative “bags of words.” We construct two variables that capture the overall number of positive and negative words in the content supplied by each province. In separate regressions we regress these on war casualties. If the news about war casualties decreases polarization in online discussions, we should see the rise in negative sentiment go hand in hand with the increase in positive sentiment, and vise versa.

Our analyses reveals that military conflict tends to polarize network discourse in Eastern Ukraine, but not in West, Central, or even Southern provinces. In the East, as casualties increased, discussions became more emotional with both positive and negative words growing in unison. This suggests that while Southern, Western, and Central provinces’ residents’ online behavior broadly show similar reaction to war casualties, Eastern provinces appear to be increasingly polarized by the conflict with negative sentiments going hand in hand with positive ones.

No matter how we approach the topic we find evidence of differential online behavior in Eastern and Western provinces, which casts strong doubts on the notion that Ukrainians altogether are becoming more united in the face of the challenges to the country’s territorial integrity. When it comes to the social media communication, we see no results that would be consistent with increased sense of solidarity that goes beyond proximate geographic loyalties. The prospects are therefore gloomy and encouraging at the same time. Despite the hopes of well-intentioned political activists and full-hearted Ukrainian patriots, it is too early to claim the victory for the inclusive all-Ukrainian nationalism based on civic rather than ethnic identity. The promise lies in the fact that both the West and the East appear to be increasing online activity and actively building social ties with the neighboring provinces, with the West also showing strong solidarity with other parts of Ukraine. More efforts to engage eastern counterparts have a promise of reducing the regional fragmentation in the future.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations