How does one know if Ukrainian authorities have now learned to prudently plan revenue and spending? How does one evaluate the 4 thousand words of the text and the 2 to 3 thousand table rows of the State Budget to understand whether or not this year’s planning is better? Our rankings provide an answer that takes into account compliance with the budget procedure and the most important budget parameters.

VoxUkraine has rated budget processes since 2018. The rankings show the extent to which the budget approval process is in line with the Budget Code. As well as how coherently the Ministry of Finance and the Verkhovna Rada work together. It is no secret that both “bargaining” and “blackmailing” occur in the process of adopting the budget, with MPs trying to fund projects of importance to them and the Ministry of Finance seeking to maintain the realism of the country’s major financial plan and facilitate its implementation for themselves.

The first budget rankings thus took into account compliance with the deadlines for budget adoption and the extent to which MPs managed to inflate spending and the budget deficit compared to the version originally submitted by the Ministry of Finance. In 2020, we added another rating factor, namely the number of legislative provisions suspended by budget law (because it is generally not allowed). This year, we added another rating factor, namely countercyclicality of the budget deficit. Meaning that the deficit may widen during economic crises as the Government tries to support the economy, but it has to be low during periods of growth. For detailed methodology, see the end of this article.

Overall rankings

The 2019 budget remains the best. It was drawn up by the Ministry of Finance headed by Oksana Markarova and approved by the Verkhovna Rada of the 8th convocation (this budget was adopted in close cooperation with the IMF). Last year’s budget (2020) ranks second.

| The minister that prepared the budget | Budget year | Overall score (the average of the rankings in all categories) | Overall ranking |

| Oksana Markarova | 2019 | 5.00 | 1 |

| Oksana Markarova | 2020 | 5.71 | 2 |

| Ihor Mitiukov | 2001 | 6.00 | 3 |

| Oleksandr Danyliuk | 2017 | 6.00 | 3 |

| Fedir Yaroshenko | 2012 | 6.14 | 5 |

| Serhiy Marchenko | 2021 | 7.14 | 6 |

| Ihor Mitiukov | 2002 | 8.86 | 7 |

| Oleksandr Danyliuk | 2018 | 9.29 | 8 |

| Oleksandr Shlapak –

Natalie Ann Jaresko |

2015 | 9.86 | 9 |

| Natalie Ann Jaresko | 2016 | 10.29 | 10 |

| Mykola Azarov | 2004 | 10.86 | 11 |

| Fedir Yaroshenko | 2011 | 10.86 | 11 |

| Viktor Pynzenyk | 2009 | 11.14 | thirteen |

| Viktor Pynzenyk | 2006 | 11.86 | 14 |

| Ihor Yushko –

Mykola Azarov |

2003 | 12.00 | 15 |

| Mykola Azarov | 2007 | 12.00 | 15 |

| Yuriy Kolobov | 2013 | 13.00 | 17 |

| Yuriy Kolobov | 2014 | 14.00 | 18 |

| Mykola Azarov | 2005 | 14.14 | 19 |

| Fedir Yaroshenko | 2010 | 14.14 | 19 |

| Viktor Pynzenyk | 2008 | 14.43 | 21 |

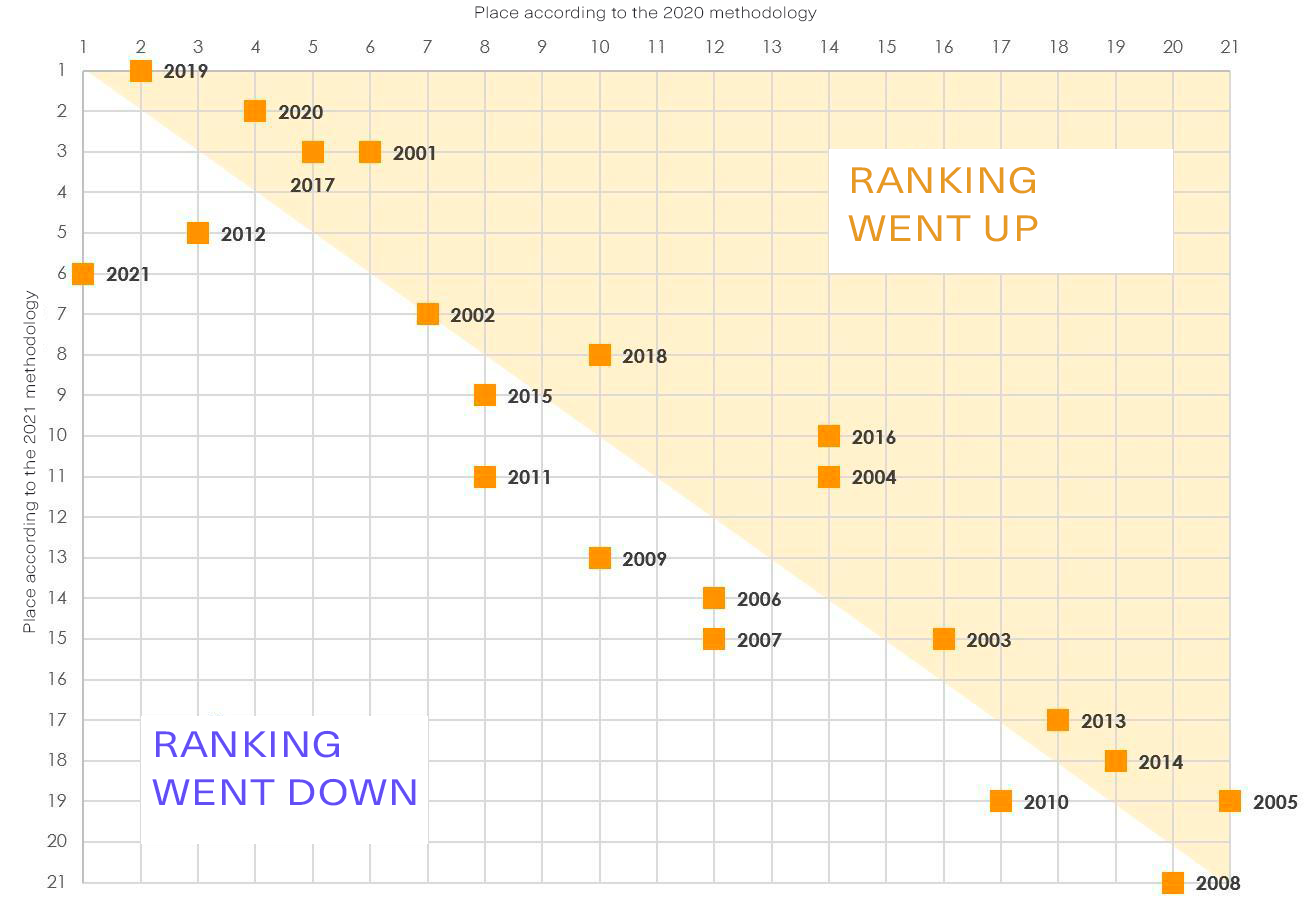

As can be seen from Figure 1, applying a new indicator did not really change the budget rankings that much. Most of all, the new indicator changed the ranking of the current year’s budget (minus 5 positions) and that of the 2016 budget (plus 4 positions), but for most other budgets the change is within 1-2 positions.

Figure 1. Budget rankings for 2020 and 2021.

Source: author’s calculations

The 2021 budget is currently in sixth place. If we apply last year’s methodology, it will come out on top because its spending and deficit decreased during consideration of the budget in Parliament. However, already before the parliamentary vote, budget deficits were twice as high than allowed by the Budget Code and remained large even after the reduction. Let us briefly look at the individual indicators we used to calculate rankings.

Budget approval period: a return to normalcy

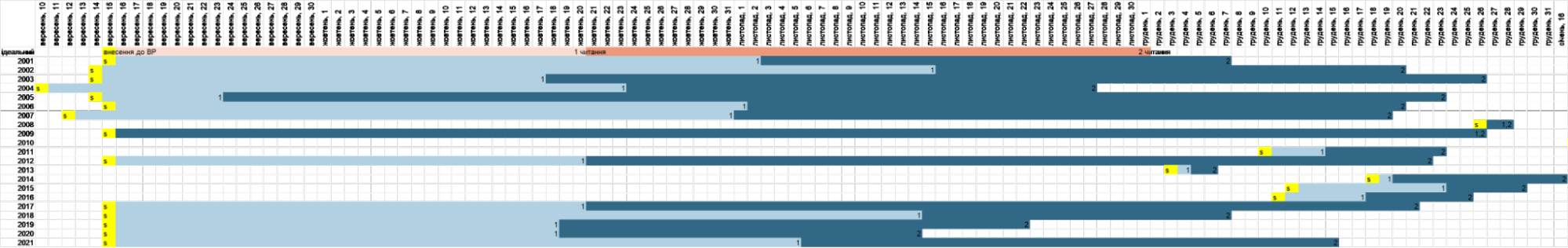

As can be seen from Figure 2, recently both the Government and the MPs have been trying to meet the deadlines for considering the budget set out in the Budget Code (BC), although consideration of the budget almost always takes longer than planned before the second reading.

Figure 2. Comparing the budget process with the “ideal” (as set out in the BC)

Source: compiled by the author. Red indicates the budget process as set out in the BC, and blue – the actual process. Darker colors indicate consideration of the budget in the 2nd reading and lighter colors – in the 1st reading. The submission date of the budget to Parliament by the Cabinet of Ministers is marked in yellow.

We see that the budgets for 2008, 2011, 2013-2016 were adopted “under the Christmas tree” (with the 2010 budget adopted on the eve of May 1). In other words, the Government was late in presenting the budget to Parliament and Parliament considered it fairly quickly. The record year here is 2010, the budget for which was submitted by the Government to Parliament on April 23, 2010, where it took 4 days to be approved. The budgets for 2008 and 2013 were adopted lightning fast – in three and four days, respectively. It is clear that such a period is too short for the MPs to work on the budget, and hence they mechanically support government proposals. In our opinion, this situation is just as bad as a delay in approving the budget. Because Parliament should participate in adopting laws, not just “sealing” the Government’s decisions.

Changes in spending and budget deficits

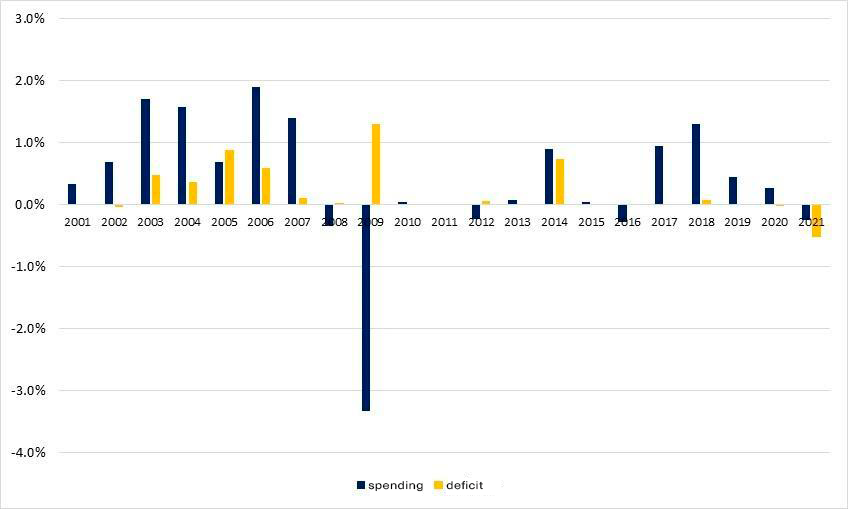

MPs always seek to increase budget spending, and they usually succeed (Figure 3). Trimming budget spending during its consideration in Parliament took place in the crisis years of 2008-2009 and 2015, when Ukraine actually did not have funds to fund the budget deficit, except for the IMF program. Spending cuts for 2012 were most likely due to close collaboration between Parliament and the Government. During consideration of the budgets for 2001-2002 and 2017-2020, Parliament increased budget spending, but not the deficit, i.e. the parliamentarians managed to find additional sources of income for their whims. However, budget spending in Ukraine is consistently underfulfilled by 2-5%. Therefore, it is possible that the governments agree to increase spending in exchange for voting for the budget to actually trim spending afterwards. Of course, this situation does not improve the quality of budget planning.

In the 2003-2006 budgets, as well as the 2014 budget, Parliament raised the budget deficit, along with expenditure. That is, the deputies actually set the Government the task of finding (i.e. attracting in the domestic or foreign market) additional funds to fund the deficit. At any rate, it was quite easy to do so in 2003-2007, during the global economic boom. Probably, that is why the governments did not actively resist the MPs’ whims.

Figure 3. Difference between spending and budget deficit in the version submitted by the Cabinet of Ministers and the final version, % of the projected GDP in the corresponding year

Source: author’s calculations. Note: a positive value is an increase in spending and deficits, a negative value is a reduction

Short-sighted fiscal policy

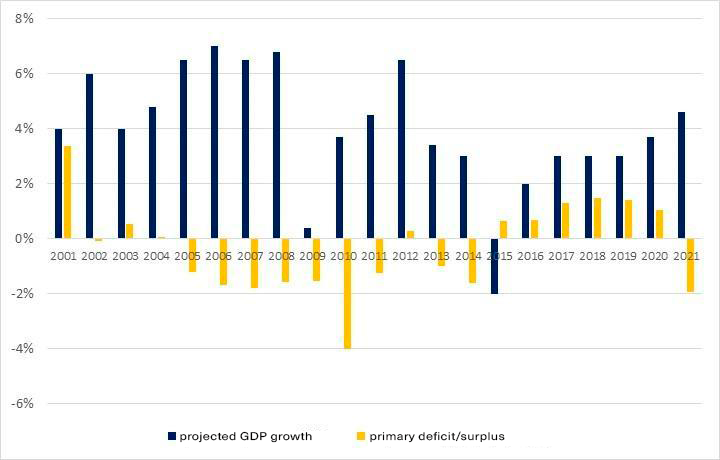

Let us look in more detail at the new indicator that we included in the calculation of this year’s rankings – the primary deficit. In theory, in the years of economic growth, a country should have a primary surplus and cut public debt, and in times of crisis, it should borrow money to fund the deficit. In practice, this was mostly not the case in the periods that we considered (Figure 4). The short-sighted policy of 2005-2014 led to the fact that in 2015, despite the crisis, Ukraine had to limit its budget deficit and have a primary surplus, albeit a small one.

This year, despite a positive outlook for economic growth, the Government and Parliament approved a budget with a primary deficit. However, in view of the pandemic situation, it is possible that this year’s government spending to support people and businesses will still be higher than usual.

Figure 4. Projected GDP growth (%) and the primary budget deficit approved by the Verkhovna Rada (% of the projected GDP)

Source: author’s calculations.

NB: for 2020, the budget approved in 2019 is taken – at the time, the forecast for GDP growth was positive.

Cutting back on spending provided for by other laws

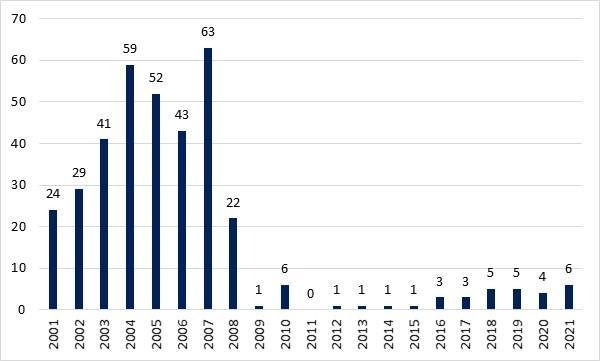

Finally, the last ranking indicator is the number of laws suspended by the law on the state budget. As one can see from Figure 5, this number has shrunk since 2009. Perhaps the reason for this is the Constitutional Court’s decision that budget law cannot suspend other laws. However, this practice continues. One of the reasons for its continuation is that some laws prescribe a minimum amount for spending in certain areas as a percentage of GDP or the budget. Sometimes, the Government cannot fund this area as prescribed, and sometimes it prioritizes other types of spending.

Figure 5. Number of laws suspended by the law on the state budget

Source: author’s calculations

For example, for the sixth year in a row, Article 24-1 of the Budget Code has been suspended that provides for funding of the State Regional Development Fund in the amount of at least 1% of the projected revenues of the state budget’s general fund. Besides, in 2021 the ceiling on the budget deficit (3% of GDP), public debt (60% of GDP) and issuing state guarantees (3% of general fund revenues) have been suspended. Public debt increased from 49% of GDP at the end of 2019 to 61% at the end of 2020 in connection with the 2020 crisis. And although the IMF predicts that the national debt will fall to 58% of GDP by the end of 2021, the Government apparently wants to be on the safe side suspending this restriction. State guarantees for this year are planned in the amount of 9.3% of the state budget’s general fund revenues. We see big risks in this budget item, but that is a topic for a separate post.

Also, among the provisions suspended for 2021 are:

- allocating part of the proceeds from issuing lottery licenses to local budgets,

- establishing minimum salary rates for court experts in the amount of 10 subsistence minimums,

- reimbursing people living in the control areas with a risk of radiation pollution (this provision has been suspended for the third time),

- approving the medical guarantees program as part of the state budget law (suspended for the second time),

- creating regional CEC offices.

Payments to the SOEs Energorynok and Ukrenergo for the indebtedness of state-owned mines, companies supplying water, and those that supplied electricity to the occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions before 2015 has also been suspended. Accordingly, there will also be no recapitalization of Ukrenergo and state-owned electricity producers through the issue of domestic government bonds.

Finally, budget law traditionally has provisions that additional payments to people in certain professions as stipulated by other laws and funding medical services will be based on budget possibilities (i.e. done in smaller amounts than prescribed in law).

One could, of course, complain about the Ministry of Finance and the MPs that supported the budget for the fact that spending in certain areas is lower than that prescribed by the law (and some politicians are actively doing so). However, adopting a law on a minimum level of funding certain expenditures will not result in more money in the budget. It can only come in as a result of accelerated economic growth, which primarily requires protection of property rights and reforms aimed at creating markets and protecting competition.

This material was prepared under the Budget Watchdog project with the support of the German Government’s project “Good Financial Governance in Public Finance III”, implemented by Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH.

Ranking methodology

In the budget rankings, we specifically assess the aspects under control of the Ministry of Finance and the Verkhovna Rada. We build up the indicators so that they depend as little as possible on the economic situation in the country, because it is only partially affected by the actions of the current finance minister and Parliament (there is also the global economic situation, their predecessors’ policies, business behavior, etc.).

Thus, three of the seven indicators assess the timeliness of the main stages of budget approval as adopting a good budget takes considerable time and requires discussing it in the committees; besides, the deputies can point to important regional issues not taken into account in the budget and to which public funds should be reallocated. We therefore view any consideration of the budget that is too lengthy or too short as negative.

On the other hand, not all the changes made to the budget in Parliament are positive. We already wrote about the breadth of the MPs’ ”whims” that overall amount to a number with twelve zeros (statistics on the 2021 “whims” will soon be published). Unreasonably inflated spending and a budget imbalance is a threat to the country’s macroeconomic stability. Therefore, two more ranking indicators show how inflated budget spending and deficits were during the discussions in the Verkhovna Rada.

Lastly, we take into account the extent to which the legal framework for drawing up such a budget was altered. This refers to the negative practice of suspending other laws by budget law, which contradicts numerous decisions of the Constitutional Court. The more regulations are suspended by budget law, the lower the score.

Detailed methodology and budget rankings for each indicator can be read here.

This year, we added another indicator to the rankings that measures the extent to which the Government uses fiscal policy to “smooth out” the impact of global crises on the Ukrainian economy.

We decided to include the primary deficit in the rankings while observing the 2021 budget discussions. Because both spending and deficits (indicators No.4 and No.5) decreased during consideration of the budget in Parliament. Overall however, this budget’s deficit relative to GDP already exceeded the limits set by the Budget Code (3% of GDP, Article 14) in its first version, amounting to 6% of GDP. Ultimately, the approved deficit is 5.47% of the projected GDP level.

Still, it is not possible to simply lower a budget’s ranking because of its being in deficit. It is necessary to take into consideration the circumstances under which this deficit arose. VoxUkraine already explained that the Government may have a deficit during recessions: the economic theory allows for spending more to support the economy. And taxes naturally go down due to reduced business activity.

Thus, if GDP growth is projected, the Government and Parliament must adopt a budget with a primary surplus, and if a decline is expected, a deficit can be temporarily allowed.

How the new indicator is calculated: we find the ratio of the primary deficit to the projected GDP for each budget. If the economy is projected to decline for the planned year and the budget is in deficit, we consider the deficit to be zero. Then we conduct a ranking. The higher the indicator, the worse the budget ranking for the year.

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations