Russians falsifies everything — from posters and leaflets to sociological studies and documentaries. Maps are no exception. However, these fakes are harmful not only because they provoke emotions or spread false narratives. They also help falsify history, especially when they end up in school textbooks. Russia has been engaging in such cartographic manipulations for centuries.

What Is mapaganda?

Mapaganda refers to the deliberate use of maps as a tool of manipulation. For instance, maps can create the illusion of control over certain territories, even if this control is disputed or illegal, or they can serve to demoralize local populations.

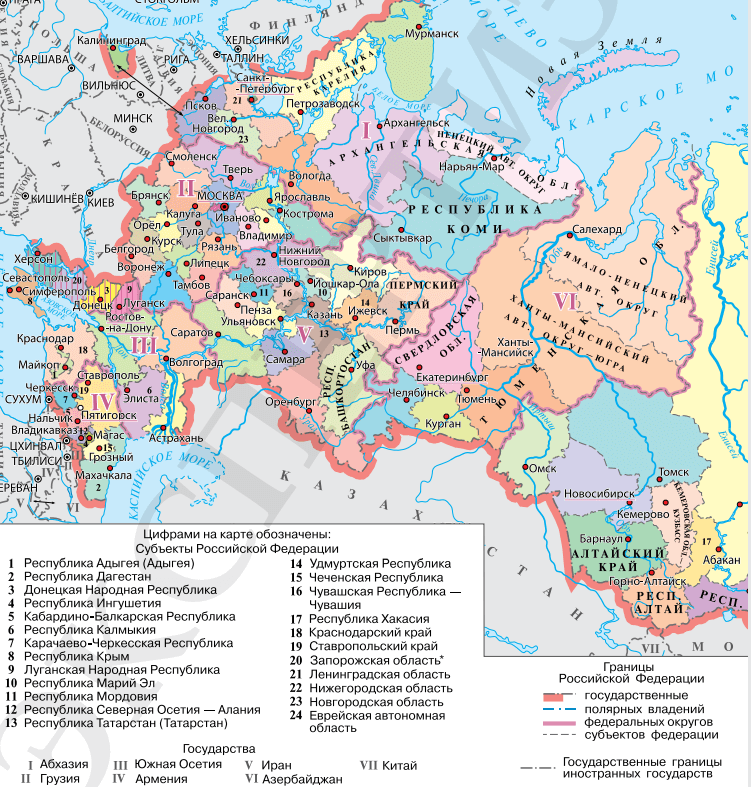

In 2023, the Kremlin introduced rewritten history textbooks for high school students, including a section on Russia’s war against Ukraine. These textbooks label the United States as the “main beneficiary” of the war and refer to temporarily occupied Ukrainian territories as “new regions” of Russia. To reinforce this narrative, the textbook includes a map showing these occupied territories as part of Russia, even falsely marking non-occupied cities like Zaporizhzhia and Kherson as Russian-controlled.

Screenshot of a Russian history textbook

These “updated” textbooks are now being used to educate not only Russian students but also Ukrainian children in the temporarily occupied territories (TOT). This is part of the Russian government’s effort to shape a pro-Russian worldview among children, turning them into targets of propaganda.

Russia’s so-called “mapaganda” has deep historical roots. It was used even in Tsarist times to spread political ideas and influence European perceptions.

Mapaganda in the Tsarist Era

“Cartographic propaganda was a significant tool when few had seen the ‘big world’ firsthand but wanted to have an idea of it,” wrote Ukrainian historian Kyrylo Galushko.

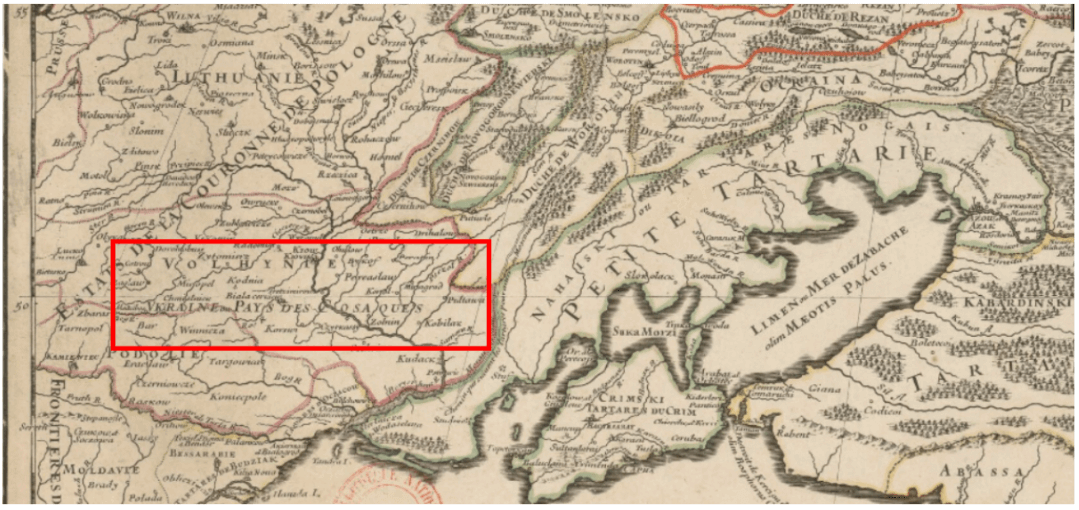

For example, Peter I wanted the “big world” to refer to Moscovia as “Russia” and to consider Ukraine — then identified as the land of the Cossacks — part of Russia. He initiated the creation of the “Russian Atlas”, which aimed to become an authoritative source of information for Western countries. Maps began to appear in European cartographic markets showing parts of modern Ukraine labeled as “Little Russia”. This historical tendency to construct an alternative reality persists in Russian policies today.

Name of Ukraine on Guillaume Sanson’s maps

Ukraine on Peter I’s revised maps

Kremlin’s mapaganda

Cartographic manipulation has never disappeared from Russian propaganda and remains a tool used by the Kremlin to influence international audiences.

Just as with Cossack-era Ukraine, today’s mapaganda seeks to “cement” temporarily occupied territories as part of Russia through fake maps — ignoring international law. The ultimate goal is to achieve de facto recognition of these territories as Russian. A pleasant bonus for them, but not so much for us, is the impact of such machinations on the emotional state of Ukrainians, both in the temporarily occupied territories and beyond. They create the illusion that the world has supposedly accepted Russia’s position.

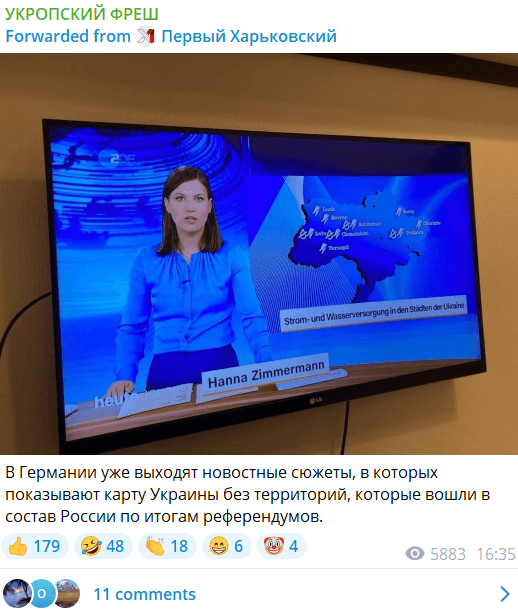

Map propaganda is a forgery of any maps, not just in atlases and textbooks. Even a map displayed during a news broadcast, a TV show, or a postcard can serve as a propaganda tool. For example, a photo was distributed online showing a map of Ukraine without temporarily occupied territories. The authors of the publication claimed that such a map was presented in the Heute journal news program on the German TV channel ZDF.

Screenshot of the post

The TV channel’s editorial team responded to the fake, stating that such an image was never aired. Instead, a completely different map was shown: one with the borders of 1991, where the temporarily occupied territories were highlighted in a different color.

Screenshot of Heute journal news, October 10

Another modern-day development is Google Maps. With the advancement of modern technologies, mapaganda is becoming increasingly sophisticated. This creates a problem for ordinary users, who find it harder to distinguish the technical features of a given platform from disinformation. Propagandists exploit this to spread fakes using cartographic resources.

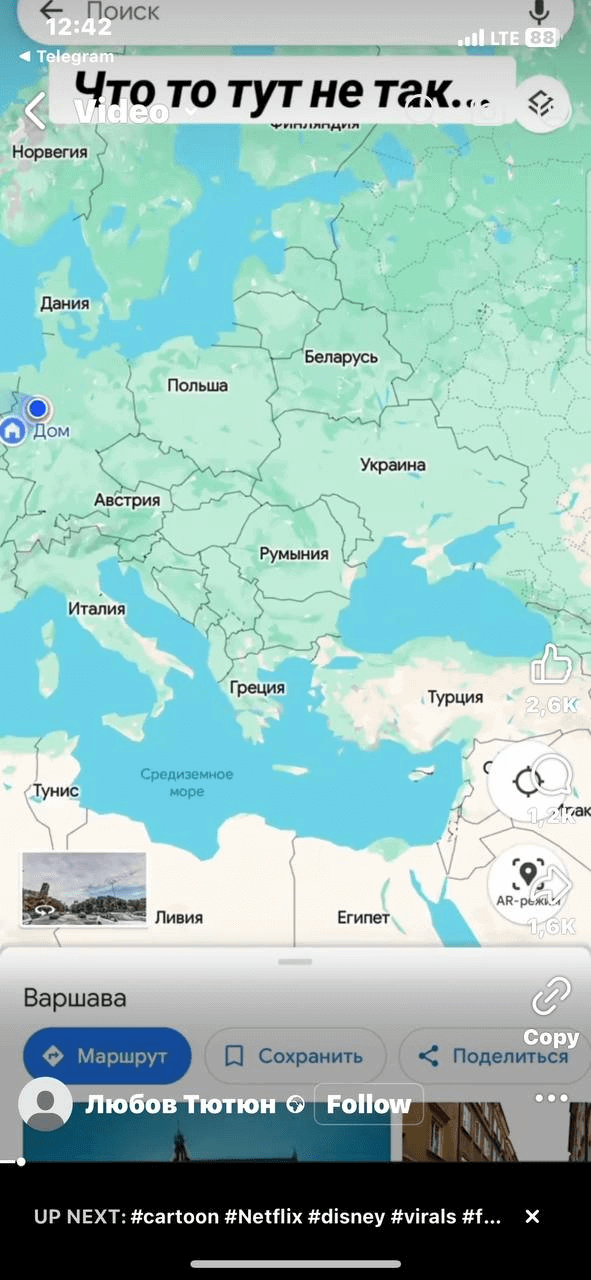

For example, a video circulated online attempting to claim that Ukraine is missing from Google Maps because European cities are listed with their country, whereas Ukrainian cities are not.

Screenshot of the post

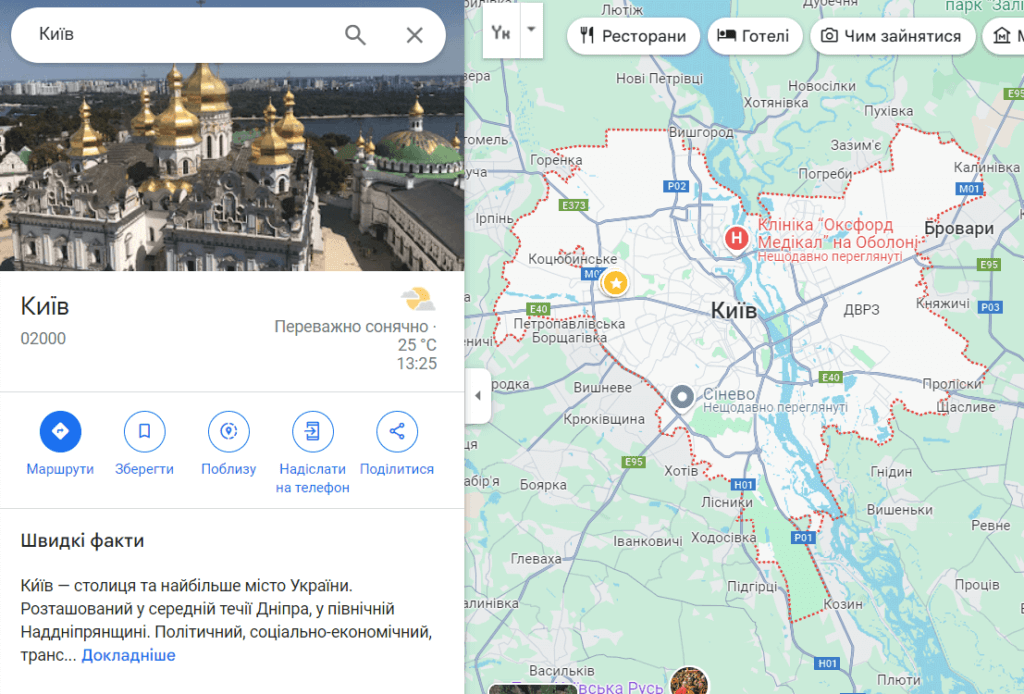

On Google Maps, the country name is indeed not specified in the description of Ukrainian cities.

Screenshot of a search in Google Maps

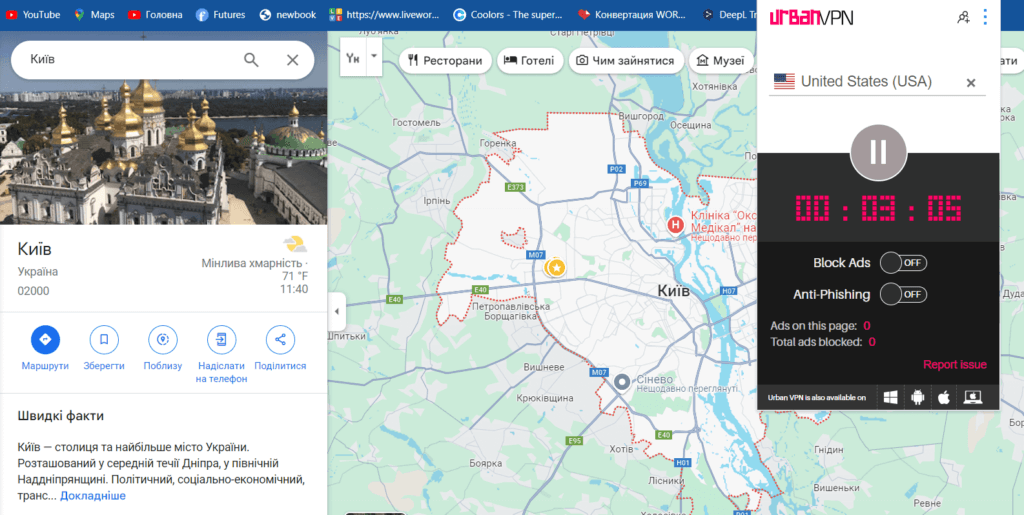

However, this is due to the program’s settings. Google Maps adjusts the level of detail based on the user’s location. That is, when a user is in a specific country, the system assumes there is no need to display the name of that country in city descriptions. If you use a VPN, Google will provide more details about cities in other countries. In the screenshot below, the description of Kyiv includes the country (Ukraine) and the postal code.

Screenshot of verification via VPN

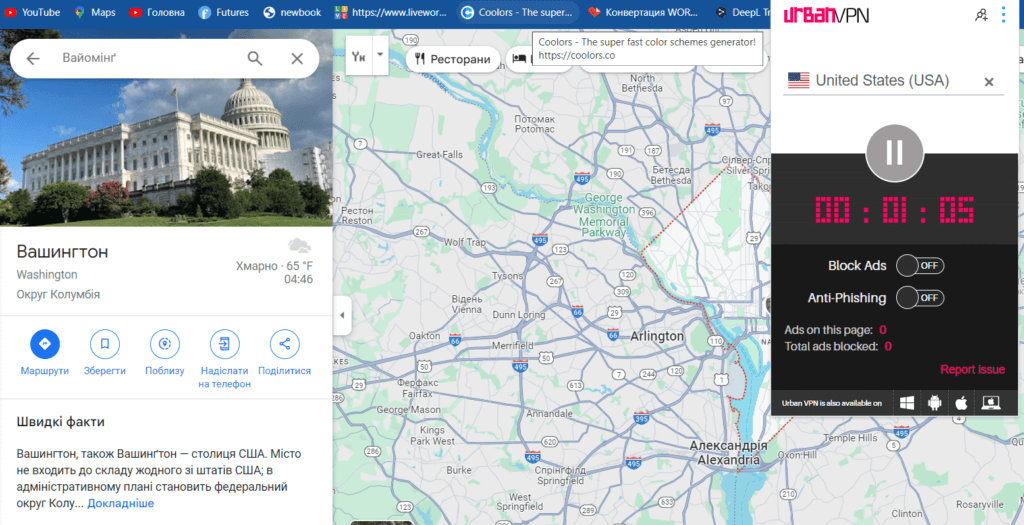

This logic also works in reverse. If you use a VPN set to the United States and look at any American city, the same situation seen in the video occurs. The description of Washington does not specify the country the city belongs to, as the system assumes that information is already known to the user with an American IP address.

Screenshot of verification via VPN

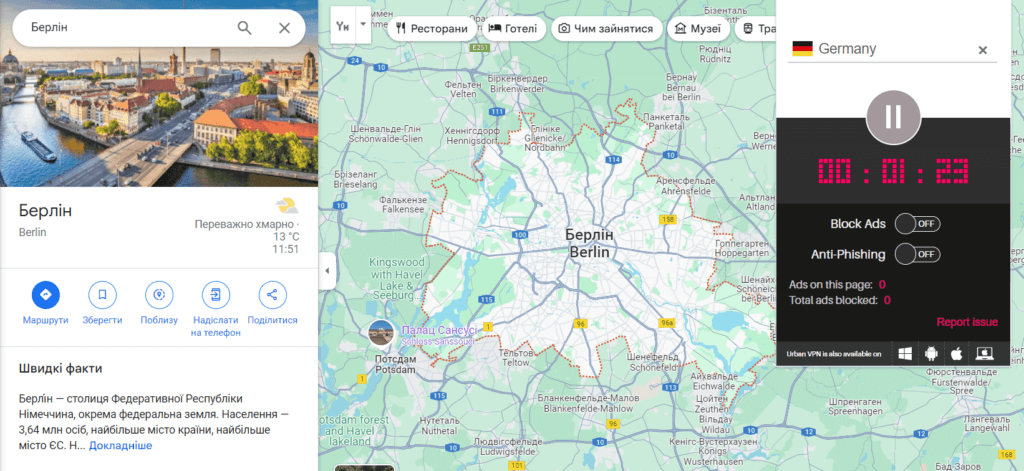

The same situation will be for other countries when using VPNs with IP addresses from those countries.

Screenshot of verification via VPN

However, the geotag in the video indicates that its author is in Germany. It is likely that their VPN is set to Ukraine, which is why Google Maps does not specify the country name in the descriptions of Ukrainian cities. As Peter I decreed, any means necessary to create the illusion that Ukraine does not exist.

Manipulating maps of military actions

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, Russian propaganda has also actively disseminated its pseudo-analyses of military actions, distorting the real situation on the front lines. Of course, this includes manipulations with maps. On such maps, propagandists distort territorial control boundaries, exaggerate Russian military successes, and downplay their losses. The goal remains the same — to create an illusion, this time of military superiority.

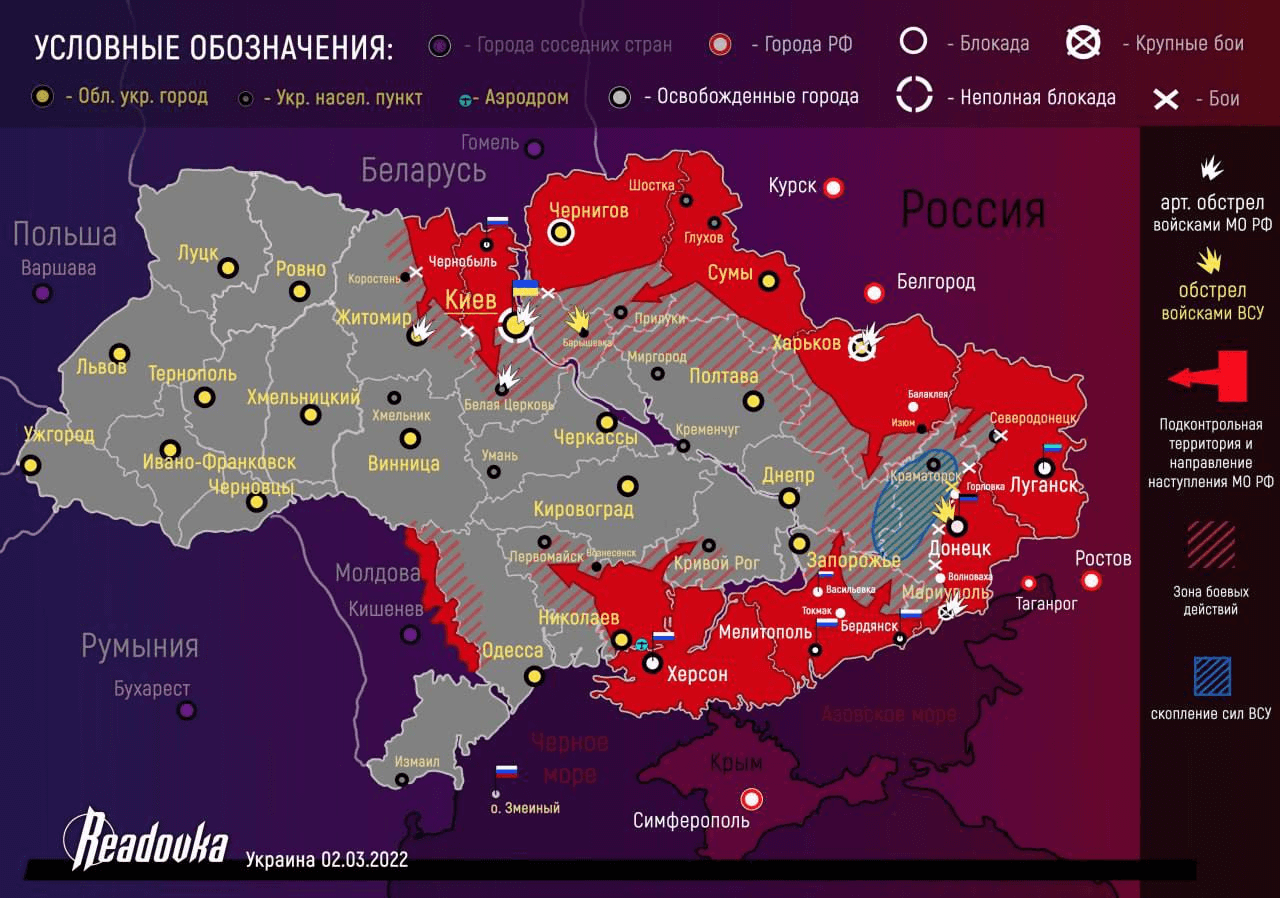

For example, in early March 2022, propagandists published a map supposedly showing the complete or partial blockade of Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, Kharkiv, and Mykolaiv, as well as alleged fighting in the Odesa region from the side of unrecognized Transnistria.

Screenshot of a fake battle map, March 2, 2022

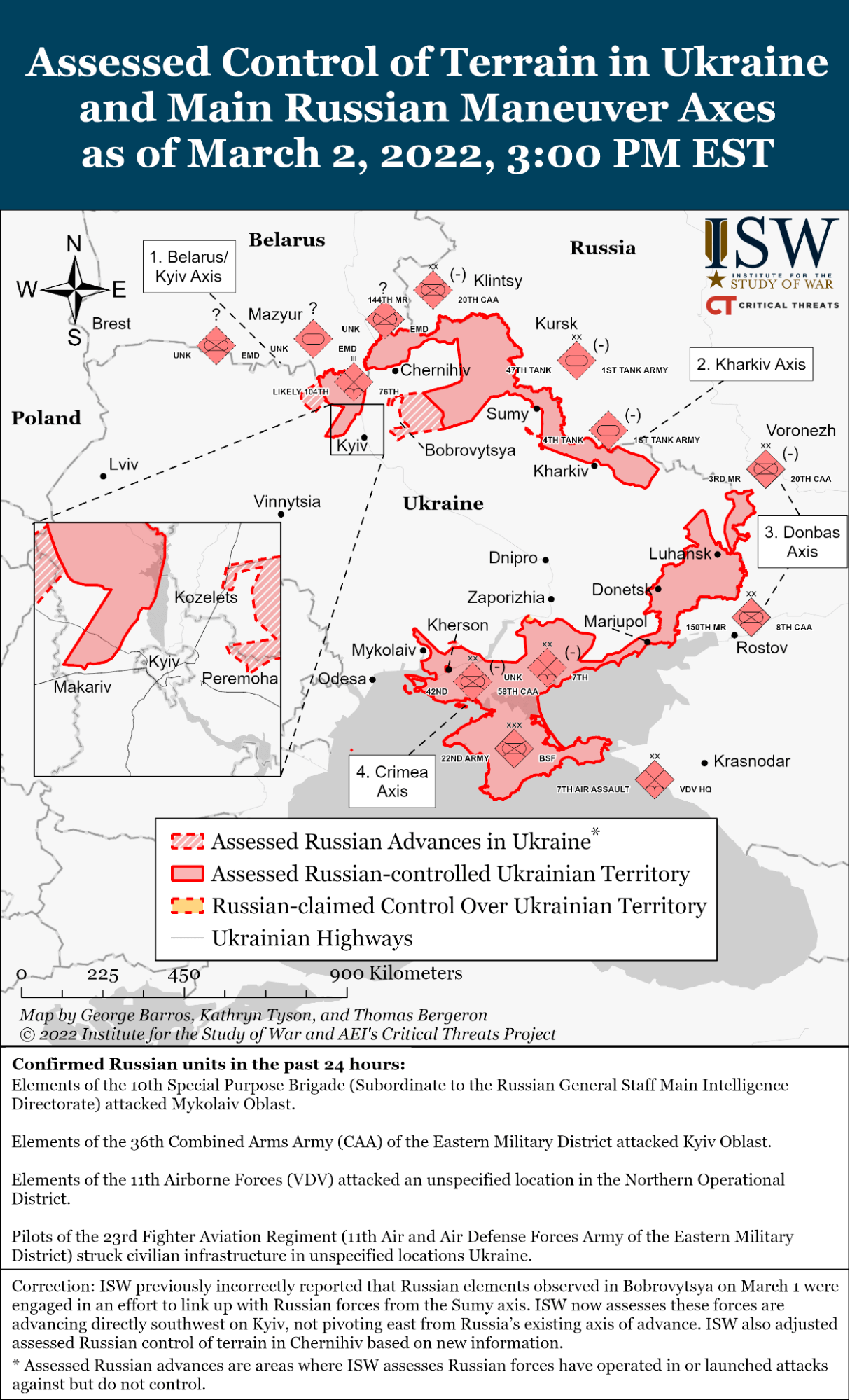

However, maps from the Institute for the Study of War presented a fundamentally different situation, which did not align with Russian dreams of a “blitzkrieg”.

Battle map, March 2, 2022

Today, military maps are still being manipulated, though on a smaller scale — since the pace of the enemy’s advance is slower than in early 2022. Russians often exaggerate the size of “red” and “gray” zones or draw massive attack arrows to spread panic in frontline areas.

How to avoid falling into the trap of mapaganda?

Manipulations with maps are a powerful tool of disinformation. Authoritarian, totalitarian states often employ propaganda to shape distorted perceptions of the world in society. As such, propaganda poses a threat to states’ national security. Countering it is necessary at both the state and household levels.

How not to fall victim to cartographic manipulations:

- Analyze the context. Where does the map come from, when was it created, who published it, and what is the message of the publication?

- Verify the source. Fakes may involve taking original information out of context, and editing photos or videos. Always cross-check with the original.

- Do not rely on a single source. Compare data from several reliable resources. For example, interactive maps like DeepState, Liveuama or Ukraine Control Map when it comes to battle maps.

Photo: depositphotos.com/ua

Attention

The author doesn`t work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations