The adequacy of using collected taxes at the local level and financing defenсe needs has become one of the most discussed topics in recent weeks and a challenge for policy-makers. With the onset of the full-scale invasion, some Ukrainian territorial communities (hromadas) received significant financial resources in the form of PIT from the monetary compensation of the military, which has sparked the most debates: How can we ensure that it is used most effectively? Should excess funds be collected and transferred to the state budget for defenсe purposes? Should allocation be based on the place of registration of defenders rather than their military unit, as it is now?

On September 12, the Cabinet of Ministers registered draft law No. 10037, which changes the principle of allocating this tax during wartime (it will be fully allocated to the special fund of the State Budget). With this article, we want to help readers understand what were the sources of funds for stadiums and drums in some hromadas and what consequences various policy proposals might have for territorial communities. We model five potential scenarios for redistributing the military PIT and assess the impact of each on the state and local budgets.

What has changed in the budgets of territorial communities after the invasion?

The budget revenues of territorial communities have undoubtedly been negatively affected by unprecedented migration, the shutdown of businesses, logistical disruptions, and war-related destruction. At the same time, mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people into the Ukrainian Defence Forces has had another significant impact on community budgets. The military, while receiving monetary compensation, pay a personal income tax (PIT) of 18%. Of this amount, 60% is directed to the community where the defenders’ military unit is registered (in 2022-23, this percentage was temporarily increased to 64%). The remainder goes to the state (usually 25% and 21% in 2022-2023) and oblast (15%) budgets. As a result, a hromada hosting a military unit (which does not necessarily mean the actual presence of military there) receives a significant influx of funds.

At the same time, many territorial communities have seen a significant decrease in PIT collections from other sources.: 44% of hromadas received less than in 2021, and in 11% of hromadas PIT income dropped by over 20%. These are consequences of the full-scale war, including the shutdown of businesses, outmigration of people, and the general mobilization. When employees go to the frontline, the community where they used to work effectively loses the income from PIT which they paid, with the community where the military unit is registered becoming the recipient of their taxes as military service members. PIT revenue is a key contributor to community budgets, providing an average of 52% of their own revenues and 29% of total revenues before the full-scale war.

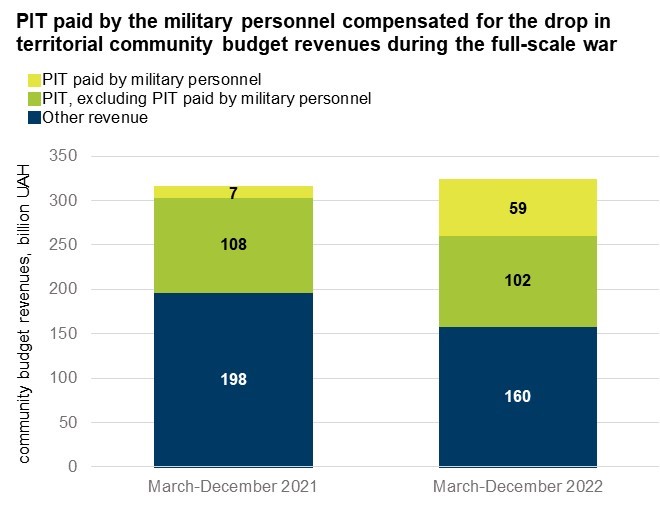

Figure 1.

Data: openbudget.gov.ua for 1302 territorial communities in the Ukrainian-controlled territories as of the end of 2022, taking into account inflation; authors’ calculations.

A sharp increase in PIT paid by the military on the one hand and the decrease in other income sources on the other have led to a shift in the distribution of funds among territorial communities. As a result, in 34% of hromadas in the Ukrainian-controlled territories by the end of 2022 own revenues increased by 15% or more, while in 14% of hromadas they decreased by 15% or more. In territorial communities where their own revenues grew by 15% or more in 2022, the increase of revenue from PIT paid by the military accounted for 94% of this growth. This can be called an imbalance in the system without an objective economic process driving it. The reason for this is PIT system in Ukraine which directs PIT revenues to where a person works (in this case the registration address of a military unit) rather than to where he/she lives.

In 2022, in 307 hromadas (almost 24% of all territorial communities), the income from PIT paid by the military accounted for more than 10% of total revenues, whereas in 2021, there were only 27 such territorial communities. Among them, 29 territorial communities not only collected more revenue from PIT paid by the military, but they also collected at least the same amount of “non-military” PIT as in 2021 (adjusted for inflation). In other 240 hromadas, military PIT revenues offset the decline in revenues from “non-military” PIT (Figures 1 and 2). That is, out of the 307 territorial communities with a significant share of military PIT in their budgets, only 38 did not receive enough of it to offset the decrease in total PIT revenues.

Figure 2. The share of the military PIT in the total revenues of territorial communities in 2021 and 2022

Data: openbudget.gov.ua; calculations by the authors

What are the risks and problems of the current system?

In the case of a radical change in the amount of PIT revenue paid by the military, the issues of fairness and efficiency in distributing these funds arise. This situation creates a scenario where some territorial communities almost randomly receive a significant component of their budget funding.

A key marker of this situation is the competition among territorial communities for the legal registration of military units. According to Ukrainian MP Vitalii Bezhin, the head of the subcommittee on administrative and territorial system and local self-government, a “constant re-registration of military units, with territorial communities engaging in a ‘battle’ among themselves” is a substantial problem. This means that hromada leaders may resort to using (informal) connections to secure this significant windfall revenue. Since April 2022, based on open budget data, we have documented more than 60 cases that seem to be related to the re-registration of military units.

This competition for resources can spark conflicts between territorial communities and create corruption risks. In 20% of hromadas, the increase in revenue from military PIT not only compensated for the decline in other income sources but also allowed them to increase their overall revenues. This is a desirable outcome for local leaders in a situation where competition between territorial communities cannot be transparent.

However, for territorial communities that have received the most military PIT and where this source has become significant for budget funding, there is a considerable risk of bearing a substantial financial burden due to the reverse subsidy.

Basic and reverse subsidies

The legislation provides for what is known as horizontal equalization of community budgets based on the tax capacity index. This index is determined by the ratio of PIT revenues per capita in a community to the national average. Territorial communities that collect less than 90% of PIT per capita national average receive a basic subsidy to raise these revenues to 90%. Hromadas that collect more than 110% of the national average must return half of the “surplus” as a reverse subsidy to the state budget, which partially finances the basic subsidy. The difference between the basic and reverse subsidy is funded from the state budget.

For the calculation of reverse and basic subsidies in the first post-war year, territorial communities will take into account the currently planned indicators of PIT revenues, which are significantly influenced by the PIT paid by military. This revenue is expected to decrease substantially after mass demobilization. Therefore, a community that hypothetically expects to receive significant PIT revenue may become a payer of the reverse subsidy. However, based on actual figures, it may very well find itself among those needing a basic subsidy. This situation would represent a double blow to the budgets of such territorial communities. They will not only fail to receive funds from “military” PIT and the basic subsidy to finance their essential needs but also be forced to become financial donors to other hromadas.

Are territorial communities that have experienced a significant increase in PIT revenue from military service members also increasing their defence expenditures?

The issue of community spending during full-scale war is primarily associated with widely publicized by media cases, such as the purchase of drums for bomb shelters, high-tech vegetable cutters and frying pans for shelters in one of the districts of the capital, repaving of streets, or the repair of automobile road intersections in Kyiv, the reconstruction of a stadium in Zhytomyr for UAH 70 million, greening of the Lychakiv district in Lviv, and the purchase of flowers for UAH 1.5 million in Lutsk.

However, it should not be assumed that the territorial communities spend all their “additional” resources on asphalt or stadiums. In the hromadas mentioned above, total capital expenditures decreased by UAH 6.5 billion compared to 2021.

Despite significant additional revenues, territorial communities’ expenses on defence are relatively small. Let’s consider the 265 hromadas that, during the full-scale war, not only managed to maintain their own revenues at the 2021 level but also multiplied it thanks to the PIT paid by the military. These territorial communities received an additional UAH 22.5 billion from the military PIT, which resulted in their combined revenues increasing by UAH 16.1 billion year-on-year. However, these hromadas only spent a total of UAH 27.9 million, or 0.17% of the net revenue growth, on territorial defence. They also spent an additional UAH 9.4 million on mobilization preparation (which may include expenses such as fuel for military transport). Out of all the territorial communities in Ukraine, only nine used the opportunity to transfer funds for the army’s needs to the state budget through a special subsidy, contributing from UAH 50,000 to UAH 5 million.

However, it would be unfair to talk about hromadas being inactive, as they bear other defence-related expenses that are extremely challenging to quantify from open sources and determine their share in the territorial communities’ budget. These expenses include purchase of equipment and machinery, construction of military defence lines, urgent repairs of infrastructure damaged by shelling, etc.

Some territorial communities, such as Lviv, Khmelnytskyi, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Poltava, and others, used the opportunity to invest money from their budgets into military bonds. These bonds not only help finance the state budget but also generate income for the territorial communities. Interestingly, the Lviv community’s investment of UAH 680 million in bonds remained in the community’s budget precisely because the state did not withdraw them for the reverse subsidy in 2022.

Territorial communities also spent funds on purchasing drones for the army. According to the Center for Fiscal Policy Research, the leaders in such expenditures are Dnipro (UAH 68 million), Lutsk (UAH 14 million), Lysychansk (UAH 13 million), Ivano-Frankivsk (UAH 9 million), and the Opishnia community in the Poltava region (UAH 9 million).

There are also other ways through which local authorities finance the Armed Forces. The expenses for the purchase of drones are often not visible in defence expenditure categories if they are conducted through municipal enterprises. For example, in Dnipro, drones worth UAH 286 million were purchased by the municipal enterprise “Info-Rada-Dnipro,” and in Lviv, the municipal enterprise “Administrative-Technical Management” purchased drones and equipment worth over UAH 8 million in 2023. According to the Nashi Hroshi publication, since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, 270 orders for drones have been placed at the ProZorro system. Half of them are attributed to two organizers: the aforementioned municipal enterprise Info-Rada-Dnipro in Dnipro and the executive committee of the Kryvyi Rih City Council. Representatives of the Association of Ukrainian Cities note that local self-government agencies have purchased drones worth more than UAH 1 billion through ProZorro.

However, most of the expenses incurred by territorial communities for the military may be technically illegal, especially considering the letter from the Ministry of Finance providing clarifications to the State Treasury Service, which prohibits “planning and making expenditures that are not provided for in local budgets by the Budget Code.” Thus, regulation of procurement and provision of assistance to the military by local authorities remains an important issue. Currently, apart from the restrictions imposed by the Ministry of Finance, community expenses are regulated by the Government Resolution 590, which local governments are trying to circumvent in various ways. Two proposed draft laws – No. 9559-2 and No. 9560-1 – are intended to address this issue, regardless of whether PIT paid by the military remains in the territorial communities or not. These draft laws suggest extending the powers of local governments in assisting the military.

At the same time, there are definitely concerns about the competency of local authorities in procuring the necessary equipment for defenders and their ability to do so effectively. On the other hand, decentralizing the assistance process can reduce tensions about corruption risks because it will be easier for residents to oversee the assistance provided by their community.

What are the suggestions for PIT revenues paid by the military, and how will they impact community budgets?

The outrage over the local governments’ high-profile procurement is pushing government officials and parliamentarians towards changes in the budgetary system. However, like many discussions about policies in Ukraine, this one lacks quantitative justification. What will the impact of a specific change be? Will we unbalance the local financial system, promote fair distribution of funds, or increase local spending on defence, which is a priority?

How will the proposals that are on the table today impact the public finance system? We have modeled how various scenarios for changing the accrual and distribution system of the debated tax could alter the budget revenues of territorial communities and the state budget. When considering potential scenarios for the distribution of the “military PIT,” we deliberately do not analyze the expenditure component of budgets in the context of potential defence spending that territorial communities might engage in if bills No. 9559-2 and 9560-1 are adopted, because it is impossible to model. Instead, we demonstrate how each scenario will affect revenues since they will determine the structure of community expenditures.

Given that there is currently no data on the expected level of community revenues for 2024, we used the actual revenue data for the first 7 months of 2023 in our calculations. In addition to calculating the size of the basic and reverse subsidies, the revenue estimates provided below are modeled assuming that in 2024 they will be identical to 2023 revenues. Therefore, these numbers should be viewed as approximate estimates to understand the scale of changes that each of the proposed scenarios will cause, rather than exact predictions.

To calculate the volumes of basic and reverse subsidies, we will use the planned indicators for 2023, as prescribed by Article 99 of the Budget Code of Ukraine (the military PIT is included in them for all scenarios, except for the Ministry of Finance’s proposal). Data on the current population is taken as of January 1, 2022, due to the absence of more recent publicly available data on the total population

Scenario 1 (baseline)

We leave everything as is. The PIT paid by the military goes to the budgets of territorial communities where the military units are registered. The share of PIT revenues that goes to hromada budgets remains at 64%.

Under this scenario, the highest budgetary funding for territorial communities is retained. However, the problem of unequal distribution of billions of hryvnias among different hromadas persists (thus incentives for registering military units within their jurisdictions are even strengthened). Furthermore, there is an increased risk of budget deficits for territorial communities that have become dependent on the military PIT paid by the military due to the imbalance in the system of basic and reverse subsidies, particularly in the early post-war years.

In 2023 local budgets are functioning under this scenario. Their total revenues from the PIT for the first seven months amounted to UAH 117 billion, of which almost UAH 44 billion came from the PIT paid by the military, accounting for 37% of total PIT revenues and over 16% of all local budgets revenues.

Based on the planned indicators for 2023, we calculated that the basic subsidy for the first seven months of 2024 could amount to UAH 18.3 billion, while the reverse subsidy could be UAH 12 billion. The difference of UAH 6.3 billion would be covered by the state budget.

If the current structure of tax revenue distribution is preserved, 43% of territorial communities will have higher budget revenues after seven months compared to 2021.

This is the only scenario in which the share of PIT remains at 64%, compared to 60% in 2021. These additional 4% were a temporary measure to maintain stability in utility service tariffs, adopted back in 2021 before the full-scale invasion. Considering the Ministry of Finance’s letter “On the peculiarities of drafting local budgets for the next year,” it is unlikely that these will remain in local budgets, so we do not consider them in the rest of the scenarios.

We will compare the rest of the scenarios to the baseline.

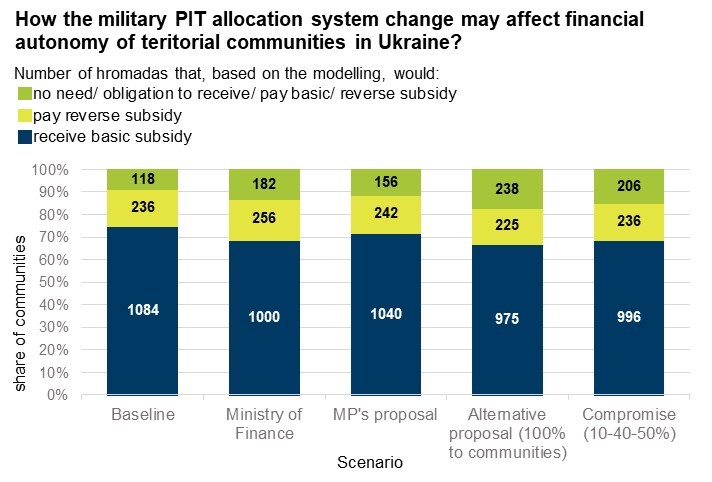

Figure 3.

Data: openbudget.gov.ua; calculations by the authors

Scenario 2 (Ministry of Finance)

The entire amount of the PIT paid by the military goes to the state budget.

The reduction of PIT revenue share going to community budgets from 64% back to 60% is an assumption used for all the scenarios except for the baseline (currently, the 64% allocation is approved by the Law of Ukraine on State Budget for 2023 (Article 23), while the Budget Code envisages 60%).

This scenario includes the vision of the Ministry of Finance outlined in the letter “On the peculiarities of drafting local budgets for the next year.” This same proposal is embodied in government draft law No. 10037. According to this scenario, the state budget will receive approximately UAH 48.3 billion more compared to the baseline scenario (+3% relative to actual revenues in January-July 2023) by withdrawing the military PIT from territorial communities and returning getting back additional 4% of all PIT revenues that were temporarily allocated to local budgets in 2022-23. The government will be able to use these additional funds to increase funding for defence needs or reduce the budget deficit, which currently exceeds 60% of GDP.

For community budgets this will mean a direct loss of one-sixth of their revenues (according to actual receipts in January-July 2023), thus increasing the need for subsidies or the necessity to cut expenses. However, due to the reduction in average collected PIT per capita, which is used to calculate the tax capacity index and the size of the basic and reverse subsidies, the state budget will only need to cover a gap of 3.4 billion UAH between basic and reverse subsidies. This is 46% (UAH 2.9 billion) less than in the baseline scenario. Therefore, along with these savings over seven months, the state budget would receive an additional UAH 51.2 billion (+3.5% relative to actual revenues in January-July 2023) or UAH 7.3 billion per month.

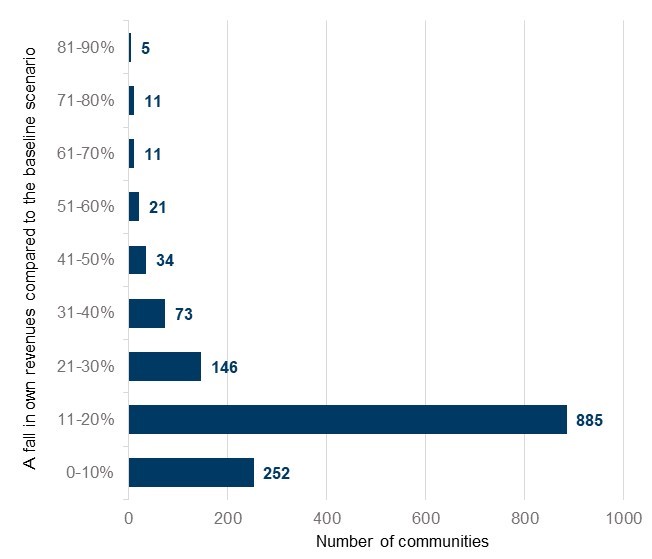

This proposal may seem very attractive to government officials. Even with the promised additional compensation subsidy of UAH 23.9 billion that the Ministry of Finance pledged to hromadas in the above letter, the state budget could still receive an equivalent amount. In relative terms, this would mean a net increase in funds for the state budget of less than 2%, achieved by reducing the budgets of territorial communities by over 21%. For every tenth community, this would result in a reduction of revenues by 30% or more.

If such a scenario is implemented by adopting the draft law No. 10037 in its current form, it would mean that PIT from the military would go to our defence sector. However, for some reason, Bill 10037 does not provide funding from this source for urgent needs such as providing quality tactical medical care, equipping military units, shelters for soldiers, their medical treatment, and rehabilitation.

Figure 4. The extent of the decrease in own revenues of territorial communities in the Ministry of Finance scenario compared to the baseline scenario

Data: openbudget.gov.ua; calculations by the authors

Scenario 3 (Vitalii Bezhin’s proposal)

The PIT paid by the military intended for community budgets is evenly distributed between the community where the military unit is registered and the community where the service members are registered.

The reduction of PIT revenue share going to community budgets from 64% back to 60% is an assumption used for all the scenarios except for the baseline (currently, the 64% allocation is approved by the Law of Ukraine on State Budget for 2023 (Article 23), while the Budget Code envisages 60%).

This scenario reflects the proposal put forward by the MP Vitalii Bezhin. These changes will help reduce existing financial imbalances since the PIT paid by the military will be more evenly distributed among territorial communities. Additionally, under this scenario, hromadas where military units are registered will continue to receive revenues to compensate for externalities such as a higher likelihood of shelling and the associated reduction in business activity (according to the MP’s statement). However, this will not eliminate the randomness of certain territorial communities receiving significant sums, and it will also leave incentives for hromadas to compete for the registration of military units, although these incentives will be significantly reduced.

We have modeled tax capacity indexes for territorial communities based on this and other scenarios using the planned indicators for 2023. To assess the impact of redirecting the PIT paid by service members from the registration location of their units to their place of residence, we use the number of male residents aged 18-60, to approximate the potential new distribution of PIT revenues. It is important to note that such an assessment does not include all groups of people involved in the country’s defence. Additionally, our modeling assumes uniform participation of residents from all territorial communities in the Defence Forces.

Modeling under this scenario shows a more even distribution of territorial communities based on the tax capacity index, with 44 fewer hromadas requiring the basic subsidy from the state budget compared to the baseline scenario (1040 vs. 1084). Additionally, it would require 25% less (UAH 1.6 billion) from the state budget to compensate for the gap between the basic and reverse subsidies compared to the baseline scenario. The state budget would also receive an additional UAH 7.3 billion from the return of 4% of the PIT. Therefore, the net positive effect on the state budget over seven months can be estimated at nearly UAH 9 billion, or approximately UAH 1.25 billion per month.

This would also enhance the financial self-sufficiency of territorial communities, reflected in the increase in the share of their own revenues by an average of 2.7 percentage points compared to the baseline scenario (56.6% vs. 53.9%).

Scenario 4 (alternative proposal)

The PIT paid by the military intended for community budgets is directed entirely to the community where a service member is registered.

The reduction of PIT revenue share going to community budgets from 64% back to 60% is an assumption used for all the scenarios except for the baseline (currently, the 64% allocation is approved by the Law of Ukraine on State Budget for 2023 (Article 23), while the Budget Code envisages 60%).

This proposal implies a complete departure from the current principle of directing PIT to community budgets. All the PIT paid by service members intended for community budgets will go to the community where the service member is registered. This proposal incorporates the widely accepted practice of personal income tax allocation in Europe.

It also addresses the issue of some territorial communities “chasing” the registration of military units. Moreover, it further reduces the inequality in the horizontal distribution of funding. Specifically, 120 hromadas (8% of all territorial communities within the territory as of February 24, 2022) will no longer need the basic subsidy or have to pay the reverse subsidy. This also means an increase in the share of territorial communities’ own revenues by an average of 5 percentage points compared to the baseline scenario.

This will have a positive impact on the state budget as well. Firstly, the state budget will receive UAH 7.3 billion from the return to the established pre-full-scale war proportions of the collected PIT directed to territorial communities and the state budget. Modeling also shows a 41% reduction in the need for the basic subsidy compared to the baseline scenario, which amounts to UAH 7.5 billion. Furthermore, the reverse subsidy will decrease by 37% (UAH 4.5 billion). This makes it possible to save half of the necessary compensation from the state budget for the gap between the basic and reverse subsidies compared to the baseline scenario. This saving is 87% greater than Scenario 3, involving the distribution of PIT paid by service members between the community where the military unit is registered and the community where the military personnel is registered.

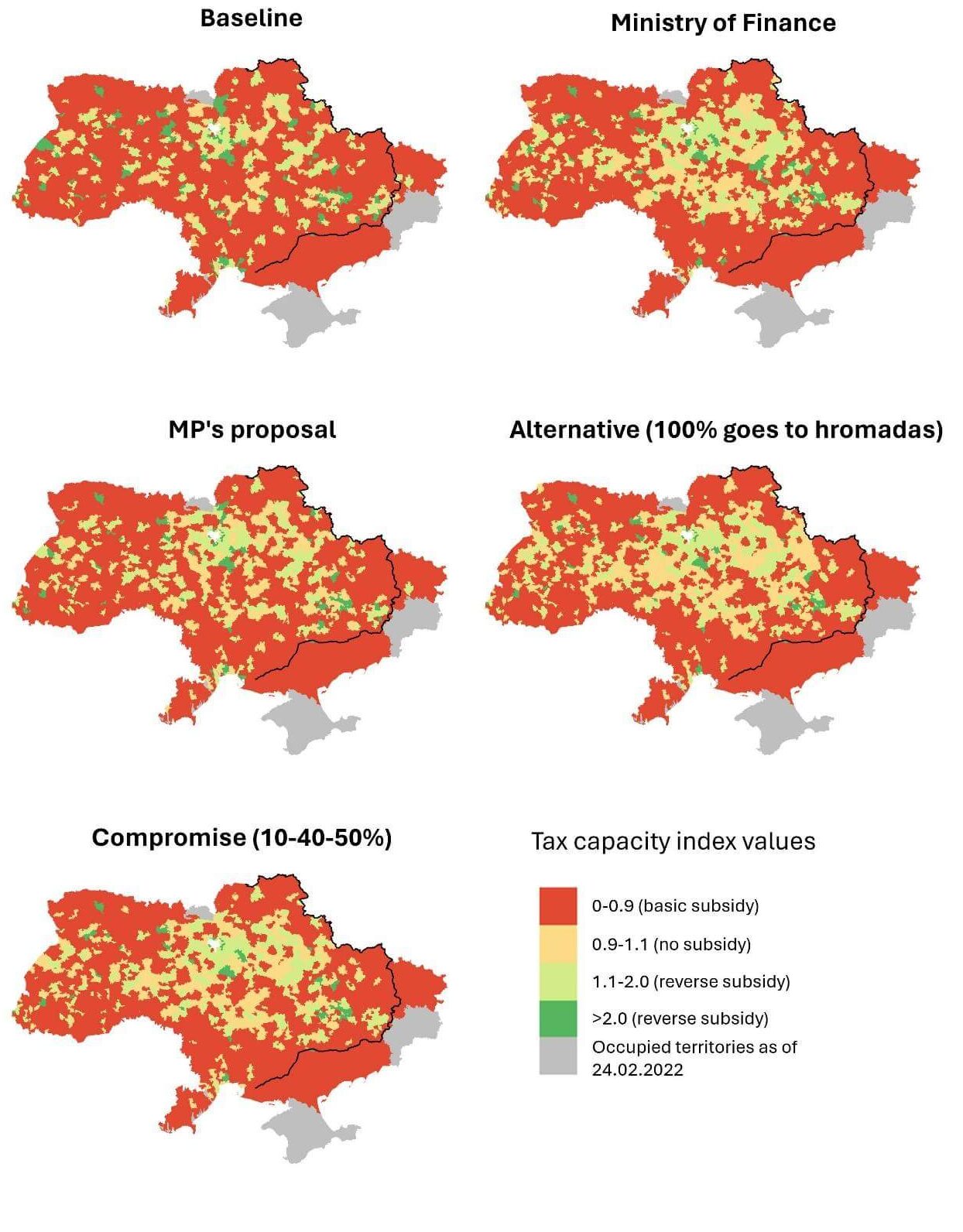

Figure 5. The tax capacity level of budgets for each of the scenarios

Data: openbudget.gov.ua; calculations by the authors

Scenario 5 (compromise, 10-40-50%)

Retaining 10% of the PIT paid by the military at the territorial communities where the military units are registered, directing 40% to the state budget, and allocating 50% based on the place of residence of the military personnel.

The reduction of PIT revenue share going to community budgets from 64% back to 60% is an assumption used for all the scenarios except for the baseline (currently, the 64% allocation is approved by the Law of Ukraine on State Budget for 2023 (Article 23), while the Budget Code envisages 60%).

Under this scenario, territorial communities where military units are registered will receive compensation for potential externalities. At the same time, directing half of the PIT paid by service members based on their place of residence will slightly reduce horizontal imbalances. As a result, 88 territorial communities will no longer need to receive the basic subsidy or pay the reverse subsidy compared to the baseline scenario.

The state budget also significantly benefits from this scenario. In this case, it will receive an additional UAH 23.7 billion from the 4% PIT withdrawal and 40% of the total military PIT. The compensation for the difference between the basic and reverse subsidies will be half the baseline scenario’s compensation. Therefore, total financial resources at the government’s disposal will increase by nearly UAH 4 billion per month compared to the unchanged revenue distribution system.

Consolidated table of scenarios in the context of revenue changes for seven months

| Scenario | Total revenues of territorial communities, UAH billion | Total PIT revenues in territorial communities, UAH billion | Military PIT revenues in territorial communities, UAH billion | Basic subsidy, UAH billion | Reverse subsidy, UAH billion | Additional revenues to the state budget, UAH billion* |

| 1 Baseline | 271.2 | 117.31 | 43.72 | 18.26 | 11.97 | – |

| 2 Ministry of Finance | 215.4 | 68.99 | 0 | 10.8 | 7.36 | 51.2 |

| 3 MP’s proposal | 259.5 | 109.98 | 40.99 | 13.94 | 9.24 | 8.9 |

| 4 Alternative proposal (100% goes to territorial communities) | 256.4 | 109.98 | 40.99 | 10.76 | 7.45 | 10.3 |

| 5 Compromise (10-40-50%) | 240.4 | 93.59 | 24.59 | 11.18 | 7.58 | 26.4 |

*Compared to the baseline scenario: additional revenues from PIT + savings on compensating the difference between the basic and reverse subsidies.

Consolidated table of scenarios in the context of consequences for territorial communities

| Scenario | Number of territorial communities receiving the basic subsidy | Share of own revenues | Average PIT per resident per month, UAH * | Average revenues per resident per month, UAH* | Number of territorial communities that will have incomes not lower than those for seven months of 2021** |

| 1 Baseline | 1084 | 53.9% | 486 | 1123 | 618 |

| 2 Ministry of Finance | 1000 | 52% | 286 | 892 | 98 |

| 3 MP’s proposal | 1040 | 56.6% | 456 | 1075 | 539 |

| 4 Alternative proposal (100% goes to territorial communities) | 975 | 58.9% | 456 | 1062 | 501 |

| 5 Compromise (10-40-50%) | 996 | 56.2% | 388 | 996 | 267 |

*Based on the modeled revenues for the first seven months of 2024

**Adjusted for inflation

What policy goals does each of the scenarios satisfy?

The scenarios outlined above provide choices depending on the government’s policy objectives in the sphere of local government funds. These objectives could include:

- Maximizing state budget revenues for financing defence needs.

- Preserving the level of community revenues and their financial autonomy while achieving a more equitable distribution and addressing imbalances caused by military PIT.

Among all considered scenarios, the smallest loss of PIT and, accordingly, total revenues for hromadas compared to the baseline will be ensured by the redistribution proposed by Vitalii Bezhin and the alternative proposal to allocate 100% to territorial communities where military personnel are registered. Also, the number of territorial communities with revenues not lower than in the first seven months of 2021 (adjusted for inflation) will decrease by 13% and 19%, respectively.

At the same time, the Ministry of Finance’s scenario is the most painful for territorial communities in terms of financial self-sufficiency, as it will reduce the average total revenue by 21%. The number of hromadas with revenues not lower than in January-July 2021 would decrease by more than six times compared to the baseline scenario. Instead, under this scenario, the state budget would receive an additional UAH 51.2 billion for defence needs in just seven months of the following year.

The compromise scenario with a PIT distribution formula of 10-40-50% falls between these extremes. On the one hand, it provides significant additional revenues to the state budget of UAH 26.4 billion over seven months, and on the other hand, it partially corrects imbalances in their distribution despite reducing financial resources available to territorial communities compared to the current situation.

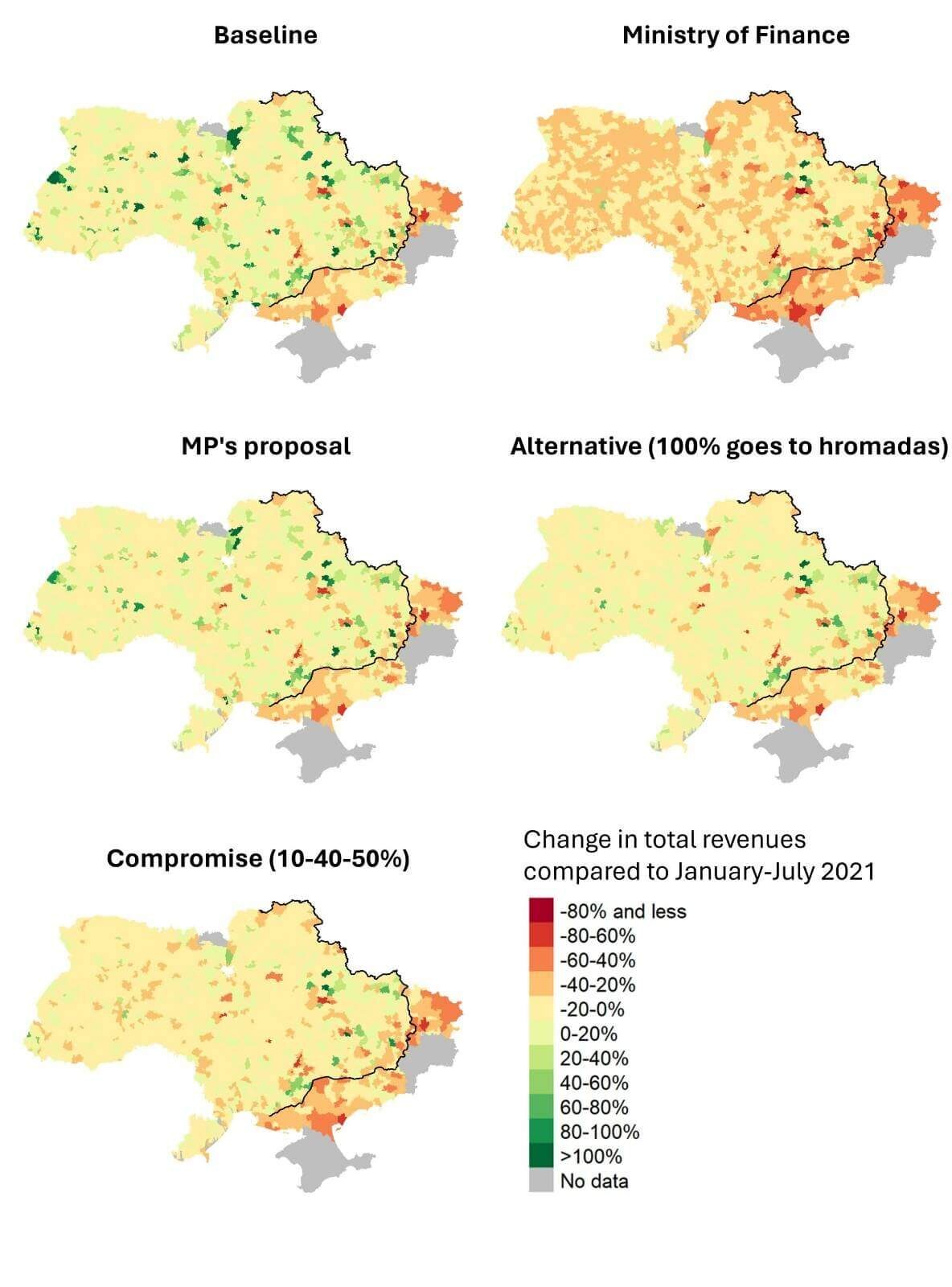

Figure 6. Change in total revenues compared to 2021 for each of the scenarios

Data: openbudget.gov.ua; calculations by the authors

Conclusions

The proposal submitted by the government to the Verkhovna Rada could become a significant factor in limiting the territorial communities’ own revenues. A high dependence of local budgets on transfers from the central budget does not create incentives for local authorities to improve the quality of life in the community. Local governments should strive to encourage more people to live in their territorial communities, work, and create businesses. Conversely, an increase in the share of subsidies in local budgets increases dependence of communities on the central government. However, among all the proposed scenarios, this one will lead to the largest revenue increase for the state budget to finance defence needs.

On the other hand, the current system of allocating PIT to where legal entities that pay to the military or other employees are registered has proven to be ineffective. The allocation of PIT paid by military personnel based on the registration place of their units has created significant imbalances in favor of a limited pool of territorial communities, leading to occasional competition for a place in this pool.

Allocating PIT paid by the military to communities where military personnel are registered can address several pressing issues at once. First, it can help distribute funds more evenly among territorial communities. This approach would also save money for the state budget, which can be used for defence purposes, by reducing the need to compensate for income disparities in local budgets. It would improve the hromadas’ financial autonomy without additional sources of revenue. Moreover, it would bring Ukraine closer to the principle adopted in the majority of European countries, where income taxes are allocated to the city or village where citizens reside and elect local authorities. This is because citizens primarily use public services in the territorial communities where they live. If the reform of PIT allocation for the military is successful, this practice could be scaled to the “non-military” PIT in the future (introducing such a practice would also gradually reduce the gap between a person’s actual and registered place of living).

There is also a compromise option of allocating 60% of the previously determined “military PIT” amount to territorial communities (10% based on the registration of military units as a potential compensator for losses associated with higher security risks, and 50% based on the registration of military personnel) while transferring the remainder to a special fund of the state budget dedicated exclusively to defence procurement.

We understand that, in practice, redirecting (either fully or partially) the PIT based on military personnel registration will lead to an increased workload for financial officers in military units. Instead of directing payments to a single budget as today, they would potentially have to make hundreds of payments to different budgets. However, since military units have up-to-date data on the registration of the military (military personnel are required to report changes in their registration), the issue is mostly technical, and these payments can be automated.

If payments based on the place of registration are extended to other types of PIT (which, however, is not expected to happen in the near future), there will be an issue of updating such information for all employees. We would not advise to burden employers with this responsibility (forcing accountants to check the registration place of employees every month is unlikely to be productive). It would be more efficient for the government to develop an electronic system containing the necessary information.

Attention

The authors do not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have no relevant affiliations